When it comes to films about Texas, it’s hard not to get hung up on the clothes. All too often, movie Texans look as though they got dressed inside a Spirit Halloween store: ten-gallon hats and cow-skull bolo ties, belt buckles the size of dinner plates, and shiny snakeskin boots fresh from the box. Those kinds of lazy exaggerations may fly in cartoons and commercials. But when it comes to seeing ourselves represented on the big screen, the fact is, clothes matter. They can mean all the difference between character and caricature.

“Indifference to detail,” as Larry McMurtry once wrote, “adds up to indifference to substance.” And McMurtry should know: he was writing, in his spare yet unsparing 1987 collection Film Flam: Essays on Hollywood, about Lovin’ Molly, the movie version of his novel Leaving Cheyenne that Sidney Lumet had directed with an indifference to detail so blatant, it verged on artistic choice.

Lovin’ Molly didn’t get just the outfits wrong, although there was plenty to lament there. The 1974 film paid so little mind to the particulars of Texas history, to its people and its geography, and to its general way of life, it remains the reigning exemplar of movies that get our state really, really wrong. Chances are, if you’ve even heard of Lovin’ Molly, it has been as the subject of mockery, probably in the pages of this very magazine. You certainly won’t find a copy on DVD, unless you’re willing to pay $100 to have a bootleg shipped over from Europe. You can, however, rent Lovin’ Molly on Amazon—or, even better, watch it on Tubi for free, which seems like a fair trade for all the effort that went into making it.

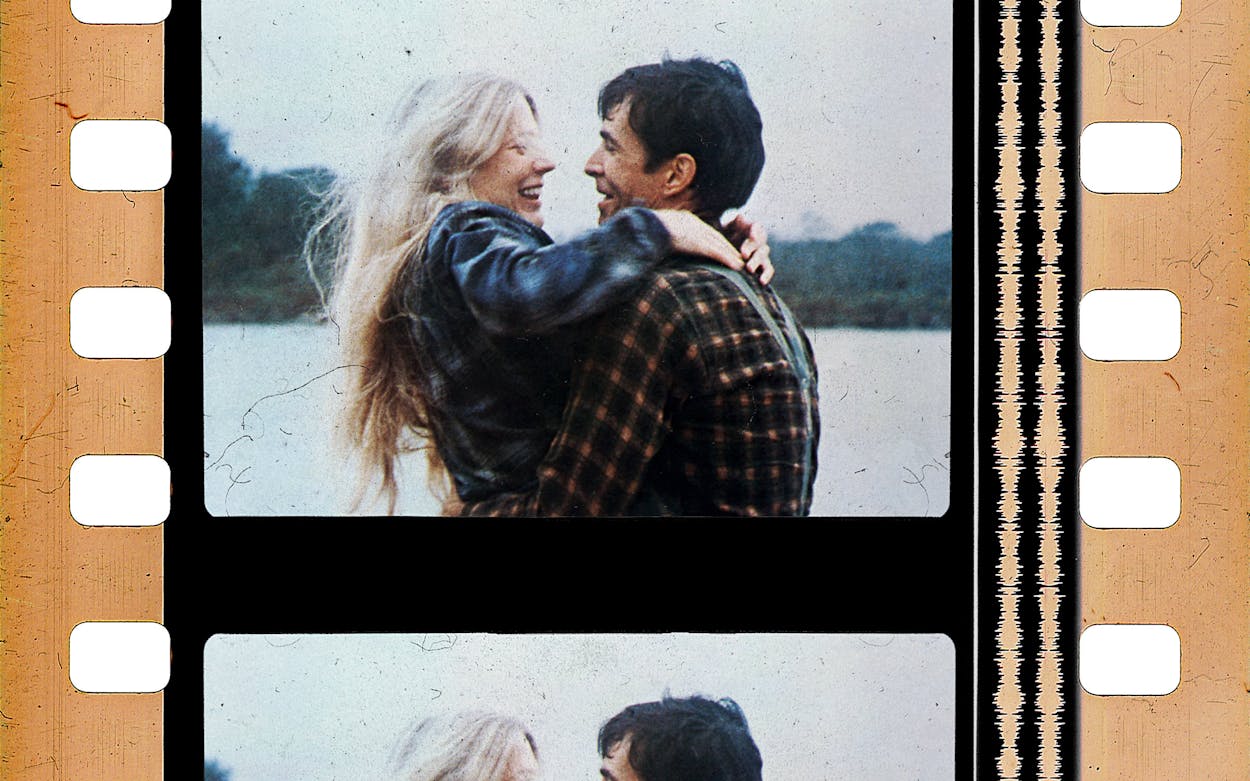

As in Leaving Cheyenne, Lovin’ Molly tells the story of a romantic triangle set against a remote sprawl of North Texas ranchland. Gid (Anthony Perkins) and Johnny (Beau Bridges) are cowboys and contentious best friends who take turns sharing the affections of the free-spirited Molly (Blythe Danner), all of them drifting in and out of one another’s lives across the span of some forty years. Although fairly libertine for its rural setting, it’s not a particularly sophisticated love story. McMurtry himself would lament that Leaving Cheyenne was little more than a male fantasy, written by a then-23-year-old with a callow understanding of how such relationships might actually play out. He wrote in Film Flam that his own naivete was cast into stark relief when he finally saw François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim, whereupon he realized that such a threesome would likely engender a little bit of jealousy and violence among its principals, rather than the light, laissez-faire teasing that Gid, Johnny, and Molly seem to enjoy. Those dangers, he noted, would surely be exacerbated by their living in a small, cloistered Texas town. Even Jules and Jim had more guns.

Still, whatever Leaving Cheyenne lacked in danger or dramatic stakes, it made up for it with its authentic sense of place. The book is set in McMurtry’s beloved fictional town of Thalia, loosely based on the author’s hometown of Archer City. Both it and Lumet’s film begin at the turn of the twentieth century, when the supremacy of ranchers would soon be usurped by irrigation farmers and oil-boom wildcatters, yet the stubborn dream of a livelihood on the saddle persisted. As it does in his other Thalia-set novels, The Last Picture Show and Horseman, Pass By, this mulishness gives McMurtry’s characters a weary grace. That Gid and Johnny are raised to be old-fashioned cowboys in a rapidly changing world gives shape and, yes, substance to this quintessentially Western tragedy.

But Lumet’s film is a tragedy of a different sort, beginning with the costumes. When Texas Monthly contributor Larry L. King was invited to visit the film’s set in Bastrop, he immediately brought the characters’ clothes up to Lumet, writer-producer Stephen J. Friedman, and just about anyone in earshot. No cowboys would ever wear clunky clodhopper shoes rather than boots. And they certainly wouldn’t be wearing bibbed “Li’l Abner overalls,” King protested. They would have been clinging to their traditional cattleman’s garb while they reluctantly plowed the arid fields of the Panhandle—to say nothing of the fact that said fields, King wrote, looked in Lumet’s film to be as lush and verdant as the “the best bottomlands of the rich Mississippi Delta.”

King doesn’t say whether he ever pointed out that Perkins’s ostensibly rough-and-tumble cowboy is dressed throughout in spotless jeans that look every bit as stiff as Perkins does astride a horse. But then, King admitted that he’d quickly worn out his welcome with the crew, who had made a point of ignoring his complaints anyway. When King objected to a clumsy brawl staged inside a train car, one full of obviously pulled punches and tender hair-mussing, Lumet sniffed that this was intentional. They were “getting away from the obligatory standard Texas machismo,” he told King, and “trying to reject the old myths.”

That’s all well and good—and really, what better story to do it with than one by Larry McMurtry, whose novels are suffused with the generational damage and spiritual emptiness that all those tall Texas myths have left behind. In fact, both Friedman and Beau’s little brother, Jeff Bridges, had done exactly that with their adaptation of The Last Picture Show in 1971. But The Last Picture Show stripped away those macho myths to get at some existential truth. Lumet just didn’t know how to stage a fight, for all his other talents. And in rejecting those old Texas fables, he created something that rang far more false.

As this is a column that is largely concerned with acting, I guess I should assess the performers’ own contributions here—something that, done correctly, might have risen above such frippery as costumes or choreography. Among Lovin’ Molly’s main ensemble, Beau Bridges probably has the least reason to be embarrassed, although the film does its damnedest to give him one. His Johnny retains a likably boyish, hotheaded energy throughout, even after the film ages everyone using some of the worst wig-work this side of a high school’s “Faculty Follies.” For one particularly mortifying scene, Bridges is stuffed into an eyesore buffalo plaid shirt with matching Kentucky colonel tie, which makes him resemble a Hickory Farms gift basket. (Okay, I’ll stop harping on the clothes.) And although Bridges is asked to shoulder some of the movie’s most tin-eared “Texas” dialogue—with Johnny whooping dunderheaded lines like “I don’t give a horse’s patoot!”—at least he doesn’t seem to mind too much.

Blythe Danner, in her first lead role (and her only, for many years) also acquits herself about as well as can be expected in a film that asks her to spend most of her time being pawed at by Perkins in the itchy-looking grass, or reciting wistfully cornpone curlicues such as “My menfolk began rising with the moon.” Plenty of contemporary critics, McMurtry and King among them, trained their ire on a scene in which Molly clutches to her bosom a newborn calf that’s slicked with afterbirth, giving it a tender kiss. But suffice it to say that any actor who can get through that without pulling a Greta Garbo–like disappearance deserves some sort of accolade.

Because this was the seventies, Danner—along with a young Susan Sarandon, who’s fleetingly glimpsed as Perkins’s long-suffering “other” woman—was also drafted into doing some gratuitous nudity, which she handles with admirable dignity. All of this fits with the film’s overall perception of Molly, dramatically simplified from McMurtry’s novel, as a sort of farmland fairy godmother who bestows her love liberally to all the town’s neediest creatures. Molly’s own desires are largely smeared away in her saccharine voice-overs or her repeated assertions that even she doesn’t really know why she does what she does. She’s ostensibly a feminist character, although her “independence” is largely about choosing which man she wants to be devoted to in that particular moment. That Molly emerges nonetheless as a sympathetic and likable presence, despite Danner’s often hammy stabs at a Blanche DuBois–esque Southern accent, is testament to the actor’s own understated charms.

I suppose this leaves us with poor Anthony Perkins, who feels the most obviously miscast here as Gid, the more traditional and taciturn of this ménage-ing trio. Gid spends most of Lovin’ Molly—and his own life—agonizing over Molly’s refusal to marry him, an anxiety that Perkins conveys largely by squirming his chin into his chest and tensing his jaw, looking for all the world like he’s about to slip into one of Mother’s dresses and start carving people up. Perkins’s attempt at a Texan dialect largely consists of an uncommitted drawl and dropping the occasional “plum” as a modifier (as in “I’m plum tired”). He seems vaguely uncomfortable in nearly every scene, as though the entire film is one of those bad dreams where you suddenly find yourself thrust into a play you’ve never rehearsed. In Lovin’ Molly’s third act, once Gid has receded into a gray and elderly husk, Perkins simply goes stiff, perhaps hoping that the camera can’t see him if he doesn’t move, like the T. rex from Jurassic Park.

Still, it’s not entirely Perkins’s fault that he’s left flailing. In fact, it’s hard to imagine any actor, even Robert Redford in his seventies prime, bringing some spark or soulfulness to a movie that’s this irredeemably inert. Lovin’ Molly was shot by Lumet with all the tactility and atmosphere of Google Street View, with no real sense of geography or scope. He manages to reduce the Bastrop countryside, already a laughably lazy stand-in for the Panhandle, to a generic blur of trees and dirt. It doesn’t just feel like you’re not really in Texas. It feels like you’re nowhere, something you could never say about McMurtry’s writing. It’s no surprise to learn that Lumet rushed through the Bastrop shoot in a matter of weeks, apparently eager to scurry off back to New York and get cracking on Dog Day Afternoon. For Lumet, Lovin’ Molly seems to have been an afterthought before it was done being conceived. It was released to reciprocal indifference.

After all, it’s not really worth getting worked up over a movie that can’t be bothered to do the same—even though indifference, when wielded this unapologetically, can feel indistinguishable from malice. For all its high-minded aspirations toward a sort of humid Southern poetry, Lovin’ Molly treads uncomfortably close to hicksploitation, from that hacky dropped g in its title to Fred Hellerman’s boilerplate score of banjo plunks and wretched, warbling harmonicas. It’s a film that takes zero interest in locating the genuine texture and spirit of our state, and this is all the more egregious for the fact that it was actually filmed here, surrounded and supported by locals who deserved much better.

“Instead of producing a work that would, in a modest way, have helped people recognize themselves,” McMurtry wrote in Film Flam, “[Lumet] has, perhaps more out of indifference than ineptitude, produced a grotesque distortion, and erected yet another small barrier to any meaningful or moving recognition. One cannot but think it a shame.”