There’s country music, and then there’s having your album listening party at the flagship outpost of National Roper’s Supply. The smell of leather, emanating from rows of saddles and other horse tack, hits as soon as you walk into the Decatur shop. Any shoe but a cowboy boot is suspect. On a November evening, Randall King, a Panhandle-born, Lubbock-bred singer-songwriter, hustled around the store in custom Lucchese boots, attending to the invitation-only crowd that had assembled in this small town, forty miles northwest of Fort Worth, to hear his album Into the Neon for the first time.

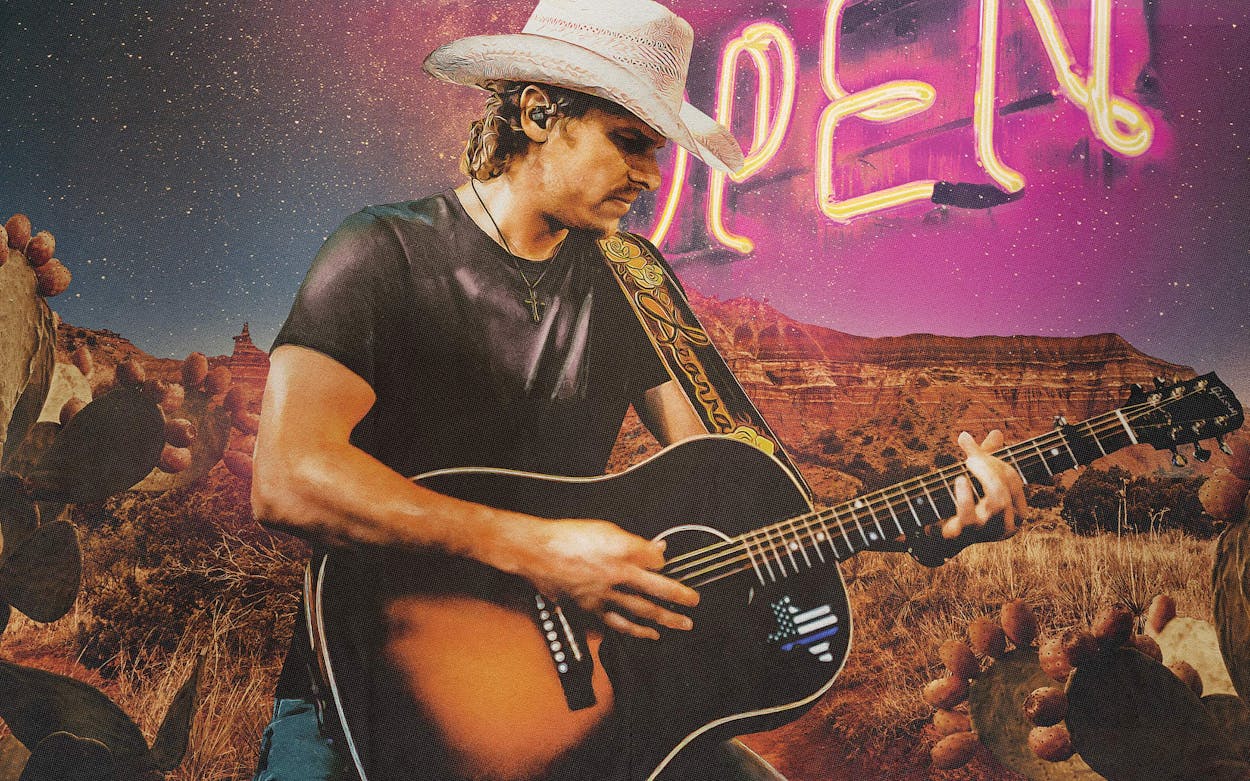

“If you took an old 1800s bar, dropped it into the Grand Canyon at night, and sipped a tequila old-fashioned under the stars, that’s what this record is,” King said. His second major-label album, released on January 26, leavens his two-step-ready sound with traces of what he calls “edge” and “smoke”—elements of the sort of easily digestible pop and rock that today’s Billboard country charts demand. He’s done so, he hopes, without losing the George Strait–inspired hard twang that fueled his rise in Texas. Fans, clad in Wranglers and Resistol coats emblazoned with King’s apt crown logo, gathered around the speakers, singing along when they heard the upbeat, Billy Bob’s–ready single “When My Baby’s in Boots.” His rottweiler, Zadkiel, whined for another taste of King’s father’s home-smoked brisket.

You’d never know that King had been at the Country Music Association Awards, in Nashville, just the night before. His Texas bona fides are unimpeachable: he’s spent years playing in the state’s honky-tonks and tiny bars. But his sights have long been set on the national spotlight and the genre’s holy grail: a number one single on country radio. “You can stay in Texas and tour for your whole life. Not interested,” said King. “I’ve seen everywhere I can see in Texas, and I love it. But I’m looking at the whole world.”

To complete his takeover, in 2020 King moved to Nashville, following in the footsteps of his near-contemporaries Cody Johnson and Parker McCollum, two radio hitmakers who have challenged the notion that Texas country is inherently incompatible with Music Row. Their success has helped bring a taste for songs laden with fiddle and pedal steel—which never left the airwaves here—back to Nashville.

King plans to take advantage of that shift. He has all the ingredients: the major label (Warner Music Nashville, which represents Blake Shelton and Kenny Chesney as well as Johnson), the big-time Music Row producer (Jared Conrad, who has crafted hits for Reba McEntire and Pentatonix), and the big-time publicist (Ebie McFarland, who handles Miranda Lambert and Strait). The question they’re all asking is whether a generation of country fans raised on streaming services—where the “everything in one bucket” format exposes listeners to countless genres—will go for King’s rootsy sound or whether his honky-tonk songs are still too twangy for country radio outside of the Lone Star State.

The 33-year-old’s upbringing in the Panhandle was humble and

unglamorous, which makes him perfectly suited to traditional country. He spent much of his childhood in Hereford (the “Beef Capital of the World”), a small town about 45 minutes southwest of Amarillo. Leaving was always part of his agenda. “Anytime anyone asked me what I wanted to do, I said, ‘I’m gonna be a singer—I’m gonna play country music.’ ”

First, King tried to do the practical thing and get a business degree at Texas Tech University. He spent all his time writing songs and flunked most of his classes. Eventually he called his dad: “Hey, I know what it took to get me here and how much money you’ve spent, but this is not in my cards,” he said, before transferring to nearby South Plains College to learn music production.

Studying audio mechanics helped set him apart from the hordes of guys writing songs with three chords and the truth, giving him the skills in the studio to craft a modern take on the traditional country sound—one that was still warm and burnished but not overly nostalgic. He coproduced Into the Neon, a level of control that helped ensure his honky-tonk style didn’t get pared down in Nashville studios.

The move also led him to the community of singer-songwriters that congregates at Lubbock’s storied Blue Light Live. King grinned

as he recounted his early performances, when he took the stage in glasses, his then long hair tied back in a bandanna. “I was a little bit hippie in college,” he said. (Now he’s “definitely redneck.”) King’s sound was rougher around the edges, more in line with red dirt rock and roll and its outsider ethos than with the buttoned-up neotraditional vintage he’s since embraced. Evidence of the period, the 2013 album Old Dirt Road, has been mostly scrubbed from the internet.

Even as he searched for his sound, King’s raw talent was

already apparent to industry heavyweights; his comanager Scott Gunter, who discovered him in a San Angelo bar, has been working with him in some capacity since 2017. In King, he heard a deep, smooth voice that instantly recalled Strait and Randy Travis; classic country stories told through a West Texas lens (“All the fences done gone up / There ain’t no cattle drive / Another bullet in the cowboy life,” he sang on an early single); and polished, danceable instrumentation reminiscent of eighties and nineties country hits.

“Coming up in Texas, you hear nothing but ‘Nashville ruins country music,’ ” said King. “Until I met [Gunter], I had no intention of going. He changed my world and my whole view on it. Nashville’s a machine, but there’s still a lot of passion within the machine—a lot of people who want to put out great music.”

Music City has often been just as skeptical about King’s home state. “ ‘He’s Texas’—that was the struggle then,” Gunter said of breaking Cody Johnson in Nashville. “Now it’s cool, which annoys me to no end. I don’t know if you saw the CMAs, but there are people wearing cowboy hats and belt buckles from the state of Georgia. It’s an outfit.” King would never be caught playing dress-up, but there’s no question that he and his label are trying to cash in on the trend.

There is a limit, though, to how far King is willing to bend. “There are things that you’re not going to hear in my music because I cannot stand them, like the snap tracks [percussion that gives many contemporary country hits a light, R&B-tinged feel] and that hip-hop-type sound.”

Within that mandate, some of his songs veer further into rock and pop territory and away from traditional boot scootin’ than others. At November’s Kingfest—his annual music festival in Luckenbach, which last year featured up-and-comers Braxton Keith and Jon Stork alongside local legend Gary P. Nunn—it was clear which style his Texas fans preferred. “Mirror, Mirror” and “You in a Honky Tonk,” two traditional two-steppers, filled the dance floors immediately.

The tracks are similar: unabashedly romantic songs that show off King’s voice amid lush beds of pedal steel as he convincingly sings lyrics that sound older than he is. Like Strait, he’s an effortless charmer. Not many singers can pull off a line like “Nothing turns me on like you in a honky tonk”—but King went viral doing just that.

“You in a Honky Tonk,” which came out in 2021, is his most-streamed song, thanks in part to significant traction on TikTok. But it still didn’t take off on country radio stations outside of Texas. “The honest truth of it is it was incredibly disappointing,” said King. “You can’t let those kinds of things eat at you, and I kind of did this year. I was angry and frustrated. I want to hear it when you walk into Walmart.” Right now, you hear it when you walk into Tractor Supply.

Even if those national dreams don’t pan out, there are worse fates than for Randall King to be the Randall King of Texas. More than 1,500 people came out to Kingfest last fall, sipping on Jerry Jeff Walker–branded sangria while waiting in the rain for King. More exciting to his team, though, was that the singer had just gotten back from his first headlining European tour, where he had—almost inexplicably—sold out most of the shows. “We were like, ‘How the f— do you know who he is?!’ ” Gunter said.

When King finally took the stage, accompanied by a light show, a projected backdrop, and a smoke machine—all inconceivable in the honky-tonks and bars where he cut his teeth—his arena-size ambitions were obvious. The sound, though, was a classic, undeniably Texan one that got people dancing in the drizzle—whether they’d heard it on the radio or not.

Dallas-based journalist Natalie Weiner has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Rolling Stone. She is the cofounder of the country music newsletter Don’t Rock the Inbox.

This article originally appeared in the February 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Straight From the Heart.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music