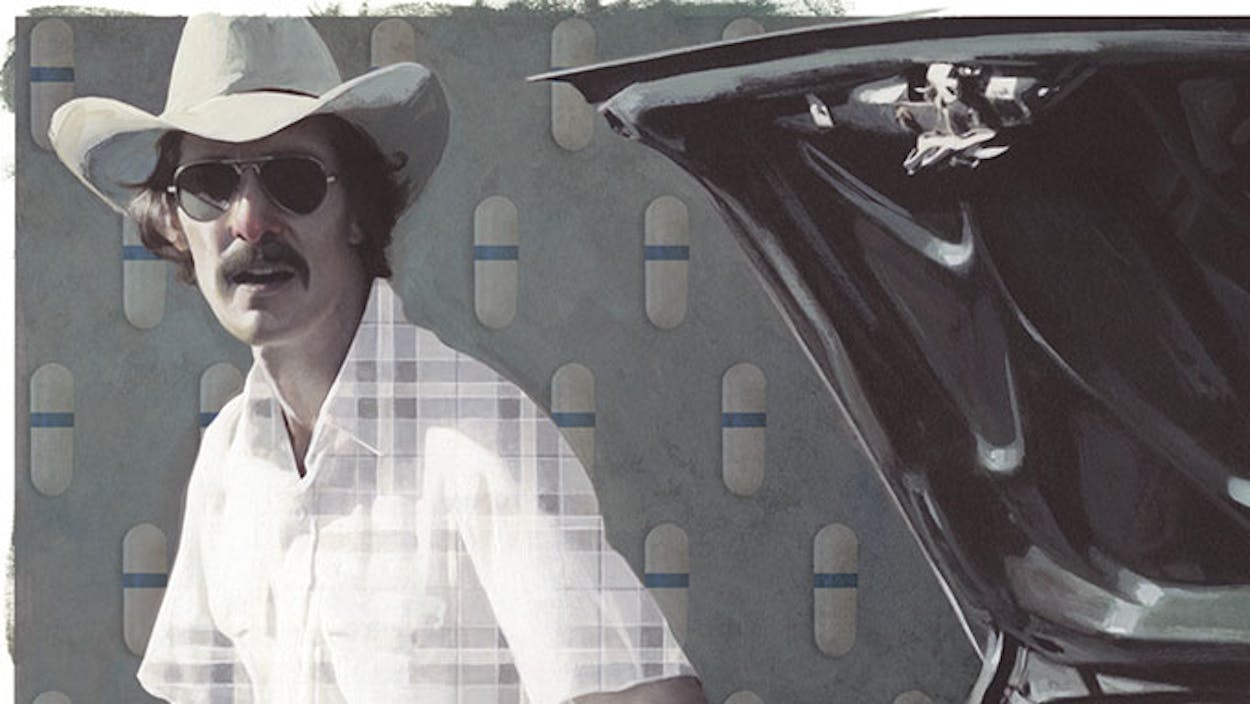

Matthew McConaughey has been on perhaps the least-expected tear in Hollywood history, serving up, in less than two years, fearlessly nervy or affecting turns in movies such as Bernie, Killer Joe, Magic Mike, The Paperboy, and Mud. After seeming out of his depth for so long (remember Amistad? Frailty? The unholy calamity that was Sahara?), McConaughey today steals scenes from the award-winning likes of Shirley MacLaine and Nicole Kidman. Now comes the fact-based drama Dallas Buyers Club, which features his most impressive transformation to date. McConaughey plays Ron Woodroof, an AIDS-afflicted electrician living in Dallas in the mid-eighties who—despite his deep-rooted homophobia—partners with an HIV-positive gay man to help fellow AIDS patients gain access to potentially lifesaving drugs.

Physically speaking, McConaughey—who dropped about forty pounds to play Woodroof—presents a harrowing vision of a once robust body in a state of rapid decay. His cheeks are hollow; his waist is no bigger than a boy’s; his famously cocksure swagger is now a bowlegged hobble. (When he removes his shirt, as he’s done in so many other films, the audience once again gasps—though this time for entirely different reasons.) Even more remarkable is how thoroughly the actor commits to this difficult-to-like character. The Matthew McConaughey of yore was a classic pretty boy who exerted little or no effort, because he knew all too well that the audience couldn’t stop ogling him. The Matthew McConaughey of Dallas Buyers Club flattens his usually mellifluous drawl and narrows his eyes in beady desperation, offering an unflinching study of a deeply cynical self-motivation. In one scene, after his physician (Jennifer Garner) suggests he attend an AIDS support group, he coldly sputters, “I’m dying. You’re telling me to get a hug from a bunch of faggots.” It’s as if he is determined to erase every last vestige of the golden-god, just-keep-livin’ persona that Killer Joe, The Paperboy, and Mud hasn’t already wiped out.

Yet as commanding a performance as McConaughey delivers—one that seems likely to earn him his first Oscar nomination come January—it’s hard not to see Dallas Buyers Club as a missed opportunity. The story takes place at a fascinating moment in recent American history, when gay men were desperately battling for access to AZT, an expensive drug that many believe actually hastened the deaths of AIDS patients. But the director, Jean-Marc Vallée, and the screenwriters, Craig Borten and Melisa Wallack, reduce all of this to a trite man-versus-The-Man melodrama, with Woodroof squaring off against heartless and money-hungry FDA reps and pharmaceutical companies to obtain access to non-approved forms of treatment. Crowd-pleasing though this may be (there’s even an outburst, reminiscent of Al Pacino’s scenery-chewing in Scent of a Woman, in which Woodroof shouts at an FDA panel, “I’m a drug dealer? You’re a f—ing drug dealer!”), it also feels like a cheat—and in the end the movie sells its extraordinary lead actor short.

Part of the problem with Dallas Buyers Club is that it falls into the same trap as countless other human-rights-themed dramas, from Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner to Mississippi Burning to Schindler’s List: it takes a story that rightly belongs to a minority group and frames it in terms of the majority character’s moral awakening. When we first meet Woodroof, he’s having a ménage à trois with two women in a rodeo pen. After he learns of his illness—presumably contracted from unprotected sex with a female intravenous drug usaer—his first response is one of disbelief: AIDS, he thinks, is a disease that strikes only gay men, whom he regards as almost subhuman. Even if you haven’t seen The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert or an episode of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, you can guess what happens next: Woodroof initially pushes away the gay men who try to embrace him, until he strikes up a business relationship—and then a friendship—with one of them, the transsexual Rayon (Jared Leto), who introduces him to countless AIDS sufferers in need of Woodroof’s help. Eventually Woodroof comes to see that gays are people too—and even defends Rayon when his boorish friend (Kevin Rankin) insults him in a supermarket. To be fair, McConaughey makes Woodroof’s transformation convincing and even touching. But at this tipping-point moment in LGBT history, with same-sex marriage legal in thirteen states and counting, it’s hard to fathom the purpose of a movie that celebrates an epithet-spewing good ol’ boy as the gay community’s knight in shining armor. Didn’t this ship sail twenty years ago, back when Denzel Washington was learning lessons in tolerance from Tom Hanks in Philadelphia?

If the emotional arc of Dallas Buyers Club is dubious, the plot is just plain creaky: a race-against-the-clock story that sidesteps historical fact for fear of muddying its central civics lesson. Given just thirty days to live, Woodroof initially tries to illegally obtain AZT from an aide at Dallas Mercy hospital. But then he meets an American doctor (Griffin Dunne) living in Mexico who convinces him that AZT is in fact toxic, and he begins an alternative therapy regimen and starts to get better. Realizing a business opportunity, he forms the Dallas Buyers Club and, with Rayon’s help, sells vitamins and non-FDA-approved drugs to hundreds of AIDS patients in Dallas, at a cost of $400 a month per patient. The FDA, however, is determined to shut him down, because—in the decidedly schematic scheme of the film—the government is in the pocket of the big drug companies and Woodroof’s club is affecting potential AZT profits. The political reality of the era, of course, was far more complicated (see last year’s Oscar-nominated documentary How to Survive a Plague or merely Google the phrase “AZT debate”), and many HIV-positive people credit AZT with saving their lives. Nor does the movie point to anything more than anecdotal evidence that the club’s regimen actually extended or saved lives. Instead, the filmmakers buy wholesale into Woodroof’s righteousness and demonize anyone who dares to object, even poor Garner, who’s saddled with the lousiest “lovable doctor” part since Robin Williams in Patch Adams.

Maybe none of this would grate so much if Dallas Buyers Club felt more authentic in its portrait of Texas. But Vallée, a Canadian, depicts Dallas as a backwater—one that seems to employ exactly one police officer (Steve Zahn)—where the gay men all congregate in a dingily lit club in some forgotten industrial corner of town. (Filming took place mostly in Louisiana; until the closing credits, I was guessing Ottawa.) It’s hard to feel generous, too, toward a movie that so insistently undermines its performers. Leto is a revelation in a part that asks him to keep stripping away (literally and figuratively) his defenses. But the film cuts short his best scene—in which Rayon visits his disapproving banker father—and does little justice to Rayon’s relationship with his devoted boyfriend. As for McConaughey, as good as he is, you’re left thinking about the ways Vallée might have allowed him to be great. There’s a scene late in the proceedings when Woodroof spies a woman among the large group of gay men lined up outside his office to purchase drugs. A devilish sparkle enters McConaughey’s eyes, along with a hint of anguish: Could it be that, at long last, Woodroof has found an attractive, HIV-positive woman with whom he can have sex?

Alas, the director cuts to a quick shot of Woodroof and the woman boinking, the audience enjoys an easy laugh, and the knotty dilemma of a once sexually voracious man struggling to reclaim his identity is abruptly sidestepped. That’s Dallas Buyers Club in a nutshell: what should be strong medicine ends up going down much too easily.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Matthew McConaughey