Tre Johnson’s three seasons of varsity basketball at Lake Highlands High School, in Dallas, were bookended by standout performances. Johnson debuted in December 2020 by scoring a team-high 30 points in a double-digit win. Last March, the six-foot-five junior shooting guard was named the most valuable player of the 55–44 victory over Beaumont United in the class 6A state championship game in San Antonio’s Alamodome.

“Tre’s just incredibly skilled,” Lake Highlands coach Joe Duffield said recently. “He’s got great size and length for a perimeter player. He shoots the ball incredibly well. He can do it all.”

Johnson is one of the nation’s most coveted collegiate recruits. Texas and Baylor are on the list of schools he’s considering, along with Alabama, Arkansas, Kansas, and Kentucky. But it appears there will be no senior season at Lake Highlands for Johnson. He has transferred to a boarding school in Missouri called Link Academy, which finished last season as the number one boys’ high school basketball program in the country, according to ESPN.

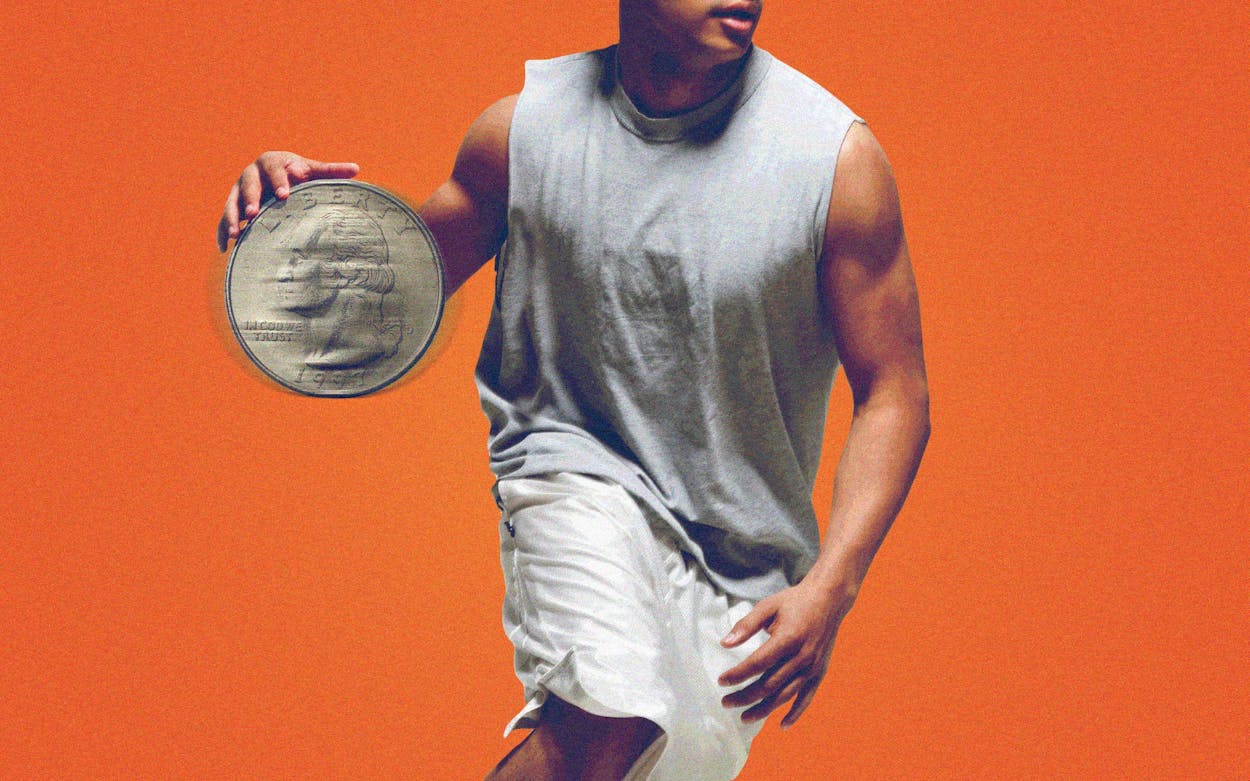

There’s nothing new about elite high school athletes, particularly basketball players, being lured away from public to private schools. What’s different about Johnson’s decision to relocate is the business strategy around name, image, and likeness (NIL) rights.

NIL became part of the American sports landscape following a June 2021 Supreme Court ruling that spurred the NCAA to abandon its longtime ban on allowing college athletes to be compensated for the use of their NIL rights, such as in video games or through jersey sales. The students became free to, like the pros, endorse products or tout restaurants and businesses.

Missouri is one of thirty states, plus the District of Columbia, that have subsequently extended the NIL rules to high school athletes, according to Eccker Sports Group, an NIL consulting firm that educates high school coaches, administrators, athletes, and athletes’ parents on NIL matters. Texas is not among those states, thanks to a 2021 state law that prohibits high schoolers from monetizing NIL rights.

Days after Johnson announced his move to Missouri, Panini America—the NBA’s exclusive trading card partner, based in the Dallas suburb of Irving—announced a multiyear deal with him. “I definitely have mixed feelings about it,” Lake Highlands’ Duffield said of the Texas law. “I see for certain athletes that can potentially move the needle in that world; I do feel like for them they should be able to capitalize off that if they’re able to. The reality, though, is that’s a really, really small number of student athletes.”

Jordan Lowery is also among that really, really small number. Lowery, a rising junior who played last season at Denton’s Guyer High, is a six-foot-one point guard who already has scholarship offers from Kansas State, Oklahoma State, Wichita State, Saint Louis, and SMU. His hometown newspaper named him the area’s 2022–23 boys’ basketball defensive player of the year. “He’s a great kid, great student,” Guyer coach Grant Long said. “Loved his coaches. Loved his teammates. We loved him.”

Lowery became a Texas basketball expatriate this summer, too, after he decided to continue his high school career at Winston Salem (North Carolina) Christian School. He, like Tre Johnson, has signed with Panini. “I’m waiting on the cards to come in and sign them,” he told Texas Monthly. “Then the money will come in.”

Lowery said the chance to earn NIL income as a high school athlete wasn’t the main reason for his move to North Carolina. Like Link Academy, Winston Salem Christian has an elite basketball program that plays a national schedule against some of the best teams in the country. “But [NIL] was like one of the pluses that went with it,” Lowery said. “For sure.”

Lowery is represented by the NIL agency Levelution Sports, which recently changed its name from Level 13 Agency in an effort to rebrand itself from a regional to a national entity. The business has offices in Lubbock and Houston, but founder and owner Kirk Noles said the operation will soon move its headquarters to the Dallas area.

Noles’s background is in art and graphic design. The Lubbock resident started Level 13 soon after the courts allowed for NIL. “I figured with the skill set and team that I had for marketing and advertising that it just fit that dynamic,” he said. Last year, the agency helped arrange the deal in which Texas Tech women’s basketball players each received $25,000 from funds raised through a Red Raiders NIL collective, the Matador Club. It also represents Texas Tech starting quarterback Tyler Shough and wide receiver Jerand Bradley.

Chris Wash, a Levelution rep who recruits and signs athletes, said he used to work in the mortgage business and ran a basketball scouting service. Lowery described the guidance he received from Wash, which included facilitating the move to Winston Salem Christian. “He talked to me about it, like telling me what would be the best decision for me,” Lowery said. “I’ve got this card deal; he got me that. One of the youngest to sign an NIL deal. It’s truly a blessing for him to help me out.”

“Do we like kids leaving the state? Absolutely not,” said Joe Martin, executive director of the Texas High School Coaches Association and a former head football coach at multiple North Texas high schools. “But to change [the law] and essentially affect every athlete in the state of Texas? Right now, that’s not something that we would promote.”

It appeared Texas’s NIL prohibition for high school students might be partially scrapped this year during the biannual session of the state legislature. Giovanni Capriglione, the state representative for the Ninety-eighth District in Tarrant County, introduced HB 1802, which would allow high school students eighteen years of age and older to participate in NIL. Capriglione’s district includes Southlake, where in the early days of NIL, Southlake Carroll High’s then–star quarterback, Quinn Ewers, skipped his senior year and enrolled early at Ohio State to take advantage of NIL opportunities. Ewers never played at Ohio State and is now starting under center for the Texas Longhorns.

Capriglione’s bill never made it out of the Public Education Committee. Jack Reed, the committee clerk, said the legislative session ended before HB 1802, among other bills, could be heard.

Unless Texas’s NIL status is amended in a special session, the topic won’t be addressed again until the Lege next convenes, in January 2025. That’s fine with Martin. “There were twenty-plus created NIL bills [nationally] in the last two years,” he said. “Since we only meet every other year in our legislative sessions, let’s evaluate what those other thirty—thirty-five states by the time we get to January 2025—what they’ve done. What did their original look like? What does their current look like? And how many times have they adjusted?”

Martin added: “Let’s learn from them before we jump in and just say, ‘The Joneses are doing it; Florida is doing it; so let’s go do it in Texas.’ Let’s be smart.”

Kelli Masters, an Oklahoma City–based lawyer and certified NFL agent who helped TCU and UT–San Antonio organize their NIL collectives, disagreed. “I am actually shocked that there are still states that don’t allow it, especially Texas,” Masters said. “I just don’t know what the reasoning is. At the end of the day, to be able to compete and to retain talent in your state, I think it’s going to become necessary. I think we’re already there, actually. It seems a bit extreme that a high school student and his or her family would up and move states just for that purpose. But for an athlete that can truly earn a sizable income from NIL, it makes sense.”

- More About:

- Sports

- College Football

- Basketball

- Lubbock

- Denton

- Dallas