In May, college football’s nascent name, image, and likeness (NIL) era came to a head. At an otherwise drowsy event gathering local business leaders in Birmingham, University of Alabama coach and SEC pooh-bah Nick Saban uttered the words that saw the sport’s message boards through the summer: that Jimbo Fisher, his former assistant and current counterpart at Texas A&M, had, by way of a cabal of deal-promising boosters, “bought every player” in the Aggies’ best-in-the-nation recruiting class.

The next morning, Fisher called a press conference to fire back. Speaking at trademark triple speed, steam piping from his ears, he defended his program against any charges of wrongdoing and challenged reporters to dig up the sordid deals in Saban’s past. But the core of Fisher’s speech came when he invoked the benevolence at the heart of the vocation that pays him $9.5 million per annum. “It’s despicable,” he said, while his face took on the shade of his maroon A&M pullover. “It’s despicable that you’re taking shots at an organization, but more importantly seventeen-year-old kids. You’re taking shots at seventeen-year-old kids and their families.”

Watching Fisher that morning, I thought of Buddy Garrity, another Texas football icon whose resonance is diminished only slightly by the facts that a) he hasn’t uttered a syllable in 11 years and b) he doesn’t, strictly speaking, exist. Buddy—we’ll skip the formalities, as he’d insist on—is the head booster for the Dillon Panthers high school football program in the late-aughts TV series and cherished regional document Friday Night Lights.

Like other characters in the show, Buddy distills an aspect of the state and the country’s relationship to football. In his case, it’s devotion: sometimes a little sweet, mostly meddlesome, always total. A season one plot hinges on the arrival of Katrina evacuee and ace quarterback Ray “Voodoo” Tatum to Dillon, which pits coach Eric Taylor’s loyalty to his current team against Buddy’s opportunism. Persuading Taylor to make a visit of questionable legality to the Tatum family, Buddy delivers a Jimbo-esque sermon after practice. “Who said anything about recruiting? I didn’t say anything about recruiting. This is about that kid whose whole family has lost everything, devastated by Katrina,” Buddy says, jowls aquiver with compassion. “It’ll help us out, and we can help him out.” Later in the episode, he’s strutting across the practice field, resplendent in sunglasses and a sweat-logged pompadour. The new quarterback—his new quarterback—is launching fifty-yard missiles and swiveling through the Panthers’ defense. “Got my Voodoo workin’,” Buddy sings, as happily as I’ve ever seen anyone do anything.

More than a decade after its final episode, Friday Night Lights has held up far better than a network-hopping teen drama by any rights should, thanks largely to its marrow-deep understanding of the characters and archetypal codes of its subject. Having won a state title does not protect good-guy quarterback Matt Saracen from losing his spot when a brighter talent comes along; for fullback Tim Riggins, yardage derives from fearlessness, which derives in turn from despair. But no one in the show’s ensemble feels as true—or, during this heady summer of NIL and conference realignment, as relevant—as Buddy, the Oz of West Texas. He is a stuffed collar and a hot handshake, a championship-ringed clap on the back, a comped luncheon with a string dangling from each riblet. He raises money so he can allocate it; he grants favors quickly and redeems them in double. At his core, the character is a man without any sense of perspective or proportion. If you’re wondering why our national sport is the way it is—in all its overloved excess, its bizarro piety, its never-ending and increasingly uncanny escalation—he’s about as good an answer as our national fictions offer.

Some other times Buddy Garrity has come to mind, in the past year: When Lincoln Riley, the decorated and well-compensated head coach at Oklahoma, left days after the Sooners’ regular-season finale to become even more well-compensated at the University of Southern California, and when a few days later he moved into a $17 million (and seven-fireplace) home in Palos Verdes Estates. When USC then left the Pac-12 conference to sign a richer contract with the Big Ten. When one Austin car dealership gave star Texas tailback Bijan Robinson a Lamborghini, and another gifted five-star quarterback transfer Quinn Ewers an Aston Martin. When Fisher sparred with an anonymous message-board commenter known only as “Sliced Bread” over the aforementioned loaf’s claim that A&M boosters had built the program a $25 million slush fund for NIL deals (NCAA bylaws prohibit boosters from offering NIL sums at the recruiting stage, to more or less the degree that Congress prohibits insider trading). When one of Fisher’s assistants, in late June, gestured up at the luxury boxes at Kyle Field and said to a gaggle of visiting recruits, “Y’all getting a lot of money from the people behind these suites if you decide to come play here.”

Public sentiment has lately, and rightly, evolved past shaming teenagers for taking their cut of an industry that generates more than $1 billion a year via their labor. Still, as NIL contracts do in the light what bagmen used to do in the dark, it’s hard not to marvel at the sheer sprawling scale of it all, now public and tally-able for the first time. In California and Ohio and Michigan and Georgia and Texas, millionaires and billionaires—by and large a group of Americans known to keep a keen eye on their margins—huck dollars with abandon at coaches, underwrite space-age and totally superfluous advances in the field of locker-room design, and bid among themselves for recruits. That they disregard what meager NIL guardrails exist is not shocking in the least; the degree to which they’re willing to do the same with their own usual standards of savvy investment is.

“Looking at this world, the figure of the booster was something that fascinated and compelled me,” Jason Katims, head writer of Friday Night Lights, told me. “A guy who’s willing to say anything, do anything, for the sake of his football team. A guy like Buddy, the fact that there might be some moral gray areas, that there might be some creative ways of looking at truth, doesn’t bother him. His growth was stunted back when he was on the Panthers; it was the greatest time of his life.” Katims tacked on the sort of follow-up conflicted football fans tend to offer after laying out the sport’s extensive faults: “I just love him.”

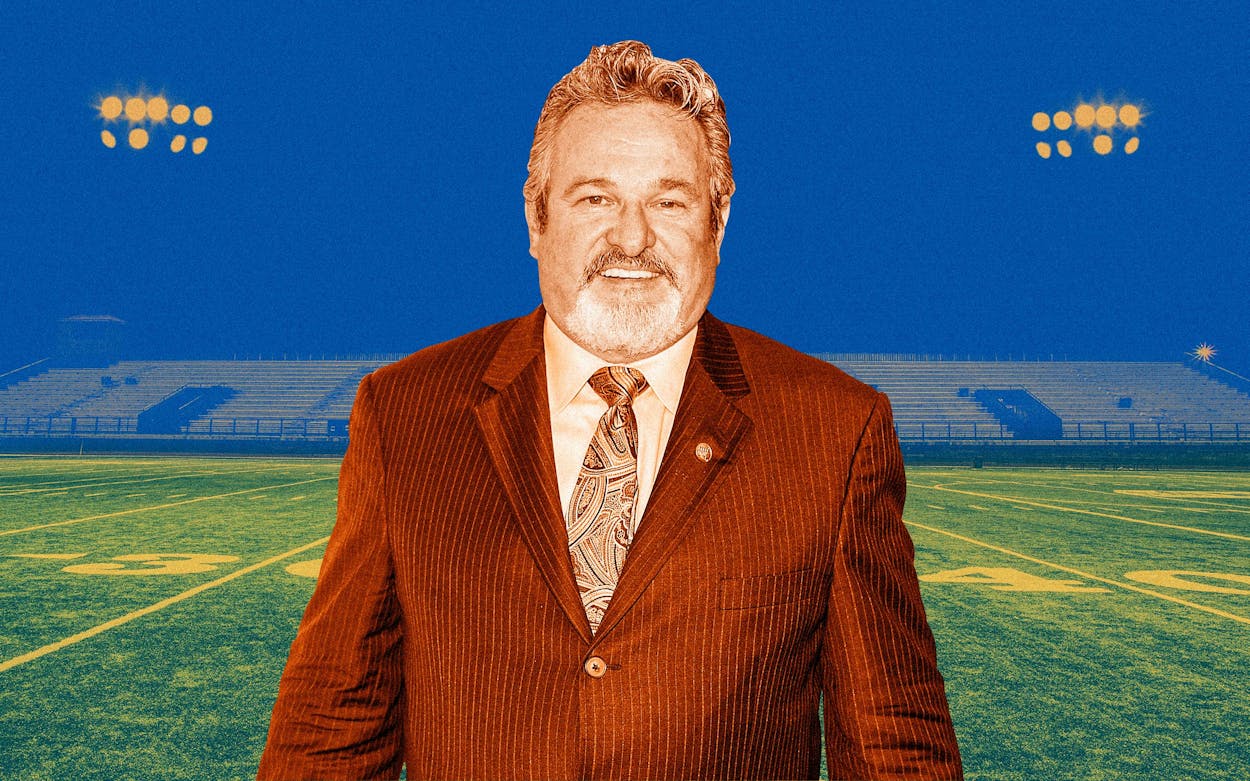

Brad Leland, the now 67-year-old Lubbock native who gave Buddy his who, me? eyes and collusive drawl, sees in the character a topography of the passions and pathologies of the booster. (Preparing for the role, Leland drew on two main inspirations: his own high school career under a saintly head coach, and an Austin-area personage who hung around the show’s set and “would never stop talking, literally ever.”) “Buddy, he got everything he ever wanted,” Leland told me. “He got a state championship in Dillon when he was a player. Then he married his high school sweetheart, and they have this perfect family. He established this very successful car dealership.” But the serenity of success can’t match the thrill of competition. “Everything was great—but it wasn’t great if they didn’t win on Friday night.”

So Buddy pursues the kind of endless adolescence available to men with enough means and without enough scruples, forever barging into Taylor’s office or the Panthers’ weight room—when does he find the time to sell any cars?—with a glossy grin on his face and something knockoff-Faustian on his mind. At various points in the series, he amends Taylor’s lineup via radio appearance, erects an unasked-for Garrity Motors–branded video board at the school’s stadium, and hammers a mailbox into an empty lot to circumvent districting rules. That ancient rite of boosterdom, slipping cash-stuffed envelopes into lockers, is nothing next to the broader and more strategically rewarding—that is to say, more vicariously football-ish—project of accruing and leveraging influence. When Tatum’s recruitment is eventually found to be in violation of the state association’s rules, Taylor and Buddy walk into a disciplinary hearing to find one of Buddy’s college chums conducting it.

Leland played Buddy in bursts of almost enviable overemotion, more teenaged than the show’s many purported teenagers. Staying at the Taylors’ home after his wife has locked him out for his latest infidelity, he decodes an imprint on a notepad revealing Taylor’s meeting with a college program interested in luring the coach away from Dillon. “A little something I learned on Magnum, P.I.,” he says, hilariously and pitifully, and when he packs up to beg forgiveness back at home, his core concerns haven’t changed. “Pam can cut off my head and put in on a spike,” Buddy tells Taylor, “but I’ll always care about the Panthers.”

Watched now, the scenes read like a parable. To love football in the twenty-first century, you have to misplace some priorities. The planet is baking, the systems are cratering, the children and young adults in helmets are sloshing their brains against the sides of their skulls. Still, the game keeps a hold on millions of fans, and I count myself among them; I belong to text threads dedicated in one part to despairing over the daily news cycle and in another (larger) part to trading clips of endorphin-igniting jukes and tackles. If Buddy has different problems than mine—the ennui of the philandering small-town baron versus the anxiety of the city freelancer—I can relate to his coping methods. This is the immersive, obliterative, extremely alluring promise of football: for three hours, nothing outside the white lines exists, much less matters. Given the money to make those three hours his world, why wouldn’t Buddy—or the hundreds of his ilk bankrolling nonfictional football teams—do so?

“There’s something so purely American about it,” Katims said. “The game itself is so adrenalized, it lends itself to extreme passion. Which lends itself to extreme behavior.”

Of course, in Friday Night Lights, as in its assorted real-life counterparts, there are drawbacks—mostly occurring when, by dint of his age or wealth or proximity to other and more responsible adults, someone mistakes Buddy for a moral authority. In season two, when Taylor has left to coach college ball and an unrelatedly brokenhearted Riggins has upped his already prodigious drinking, Buddy drives past the fullback, freshly booted from practice and walking alone on the side of the road. Riggins hops into the passenger seat of the SUV, but when Buddy prods him to to blame the new coach’s militaristic regimen, he instead shoulders responsibility: “Actually, I think I passed out ’cause I was hungover.” Gifted about as easy a wisdom-dispensing opportunity as any real or fictional universe could offer, Buddy biffs it. “I don’t want to ever hear you say that again,” he tells the high school alcoholic, tanned face pinching into an attempt at concern. “I’ve seen you play with a hangover many times, and you played like a champ.”

Over time, the show gives Buddy the sort of redemptive arc required for admission to prime-time hours. Plots move him from villain—the win-at-all-costs patriarch who all but disowns his presumed future son-in-law when football leaves him paralyzed, the cheater who squanders his daughter’s college fund on a get-richer-quicker scheme—to benevolent rogue, using his Rolodex and know-how to help Taylor build up a second, more overtly upright and heartwarmingly familial program when Dillon High splits in two. But Buddy, like the show he animates, is at his best in the buildup, before last-second wins and swells of guitars resolve the manic splendor surrounding the sport. That original, sinful Buddy would surely buck at the notion that anything needs absolving in the first place. Redemption? He’s got football.

There have been efforts, during this new era of seismic shifts and winnowing sanity in the real-life, big-money college game, to make sense of the whole thing—to guess the limits of the love of the oil barons and hedge-fund pirates and various other team-polo-wearing tycoons who pour their money into it. But the sport and the culture around it, which Friday Night Lights renders in enduring accuracy, repel reason. Fisher and Saban are pals again, USC is set to travel across two time zones to play conference games in Iowa, and the American gentry offers up its tithe.

As the Panthers make their way to a state championship in the first season of Friday Night Lights, Buddy spends an off-week fretting over a game between their chief rivals and the district’s perennial doormats, the outcome of which will determine whether Dillon sneaks into the playoffs. On Friday night, as his nerves fray, the underdogs pull out the needed victory, and the next morning he’s in an empty chapel. In a series that features a severed spinal cord, imprisonment, unplanned teenage pregnancy, rampant romantic distress, and numerous other weekly crises, this is the only time someone is heard praying in solitude. “I know that it was nothing short of a miracle, and I thank you for that miracle,” Buddy says, kneeling in front of a stained-glass window. “I know you truly are an all-powerful God to let such a crap team win.”