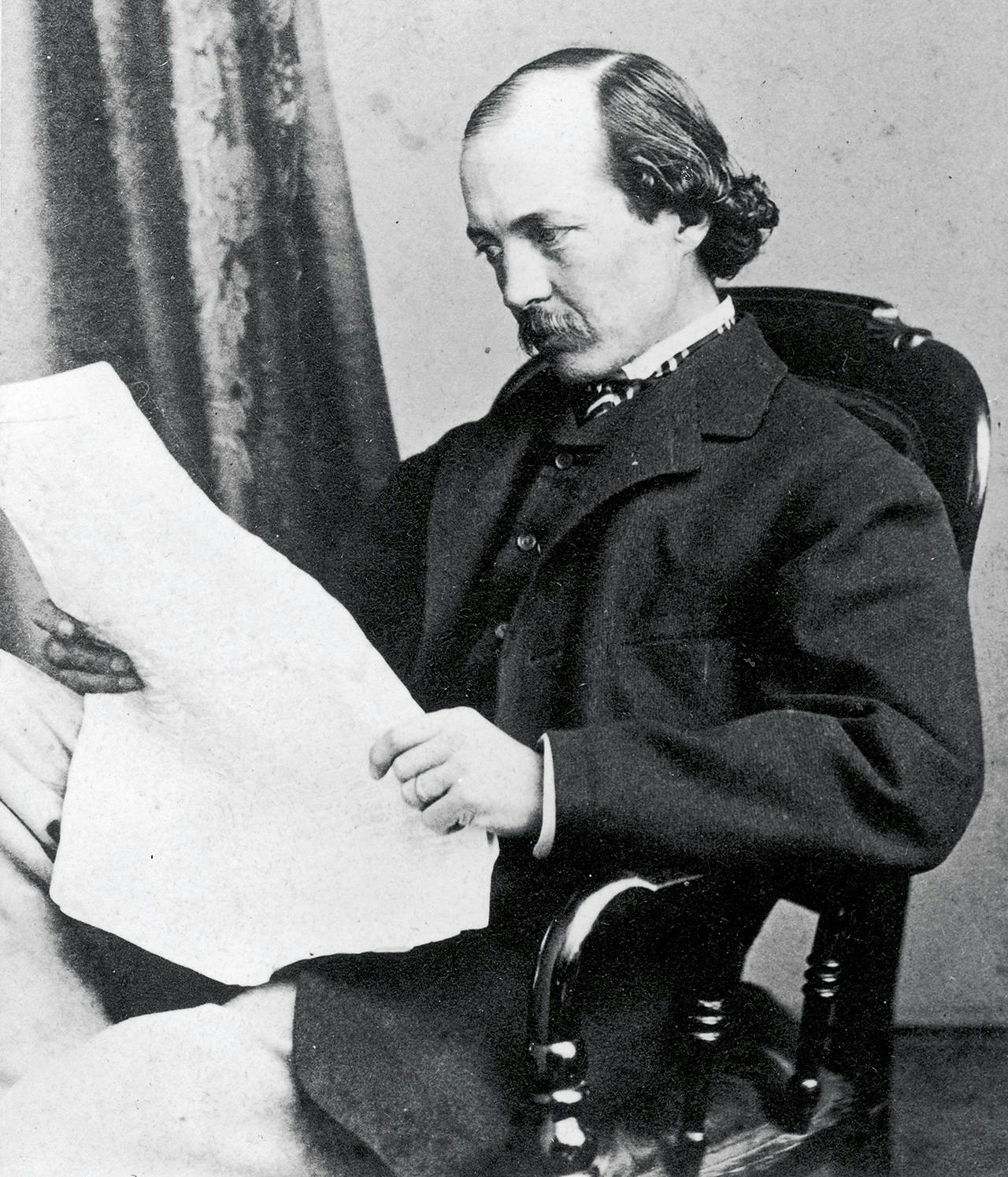

Several years ago Tony Horwitz was tasked by his wife to “ruthlessly cull” the books he had amassed as a college student during the Carter administration. Sifting through boxes stashed at their house on Martha’s Vineyard, Horwitz came across The Cotton Kingdom, an 1861 book by the New York journalist Frederick Law Olmsted—better known today as the landscape architect who co-designed Manhattan’s Central Park. The book was the culmination of several trips Olmsted had made to the American South, including Texas, in the 1850s. (His account of his rambles around the Lone Star State was also published separately as A Journey Through Texas.) Olmsted, who was then in his early thirties, had been commissioned by the New-York Daily Times to travel widely and describe the conditions below the Mason-Dixon Line, with particular attention to the effects of slavery on its economy and culture. Identified in his correspondence only as “Yeoman,” Olmsted was chosen for this delicate assignment because he was regarded as politically objective. His job, as he understood it, was “to promote the mutual acquaintance of the North and South.”

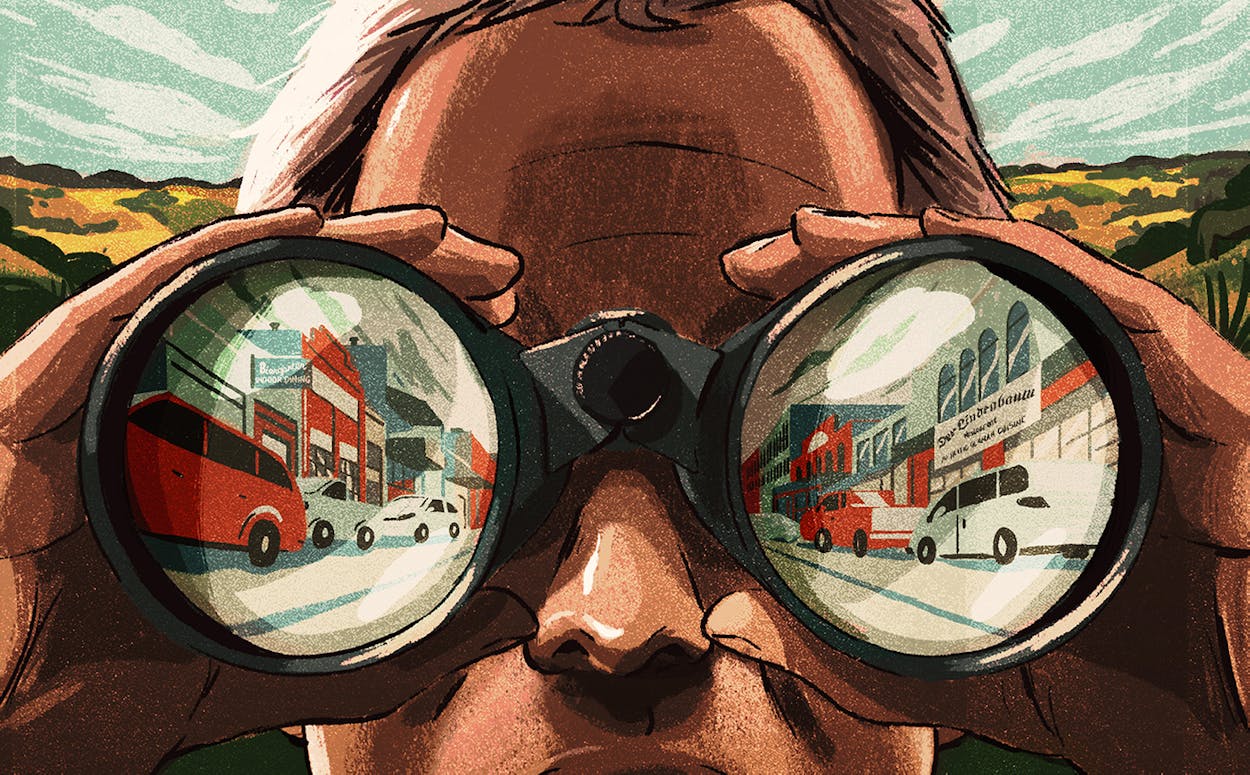

Although as an undergraduate Horwitz had merely skimmed The Cotton Kingdom, now that he was middle-aged, the book seized him. Part of the attraction, no doubt, was the affinity for travel that he shared with Olmsted; a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist, Horwitz developed his wanderlust over the course of a decade as a foreign correspondent for the Wall Street Journal. Such nomadism courses through many of his books, like One for the Road, which details his meanderings across Australia, and Boom, his quest to understand energy production in North America. Moreover, Horwitz was struck by the modern-day relevance of Olmsted’s travels, which had begun less than a decade before the Civil War. As he explains in his new book, Spying on the South: An Odyssey Across the American Divide (Penguin, May 14), “This journey had also taken Olmsted across the nation’s enduring fault line—between free and slave states in his time, and red and blue states in mine.” Noting the “inescapable echoes of the 1850s” in today’s politics, Horwitz wonders if contemporary America is “unraveling into hostile confederacies.” Or, more pointedly, he asks, “Had that happened already?” He decides to find out by retracing Olmsted’s route and sharing his observations with a divided nation, mixing history with reportage.

For Horwitz, the South is hardly terra incognita. His most successful book, the best-selling Confederates in the Attic, chronicles the months he spent among hard-core Civil War reenactors, who wear period clothing, speak in nineteenth-century dialect, and eschew the conveniences of modern life during their time in the field. Inspired, perhaps, by their commitment to authenticity, Horwitz adopts a strict protocol for Spying on the South: hewing closely to the same path taken by Olmsted himself 160 years earlier and—whenever possible—using similar means of transport. Thus, while Horwitz sets out from Washington, D.C., enjoying the relative comfort of Amtrak’s Capitol Limited, in short order he’s reporting from a massive coal towboat making its way down the Ohio River.

En route, and especially once he arrives in the Deep South, Horwitz—like Olmsted before him—regales his audience with tales of striking regional difference. In this respect, Spying on the South may remind some readers of the wildly popular 2017 podcast S-Town, which also features a Northern journalist venturing into the former Confederacy to look in on the impossibly colorful denizens of an alien land. Take, for instance, the visit made by Horwitz and his travel partner for much of the journey, Andrew Denton (described by the author as “an Australian Jon Stewart”), to the Louisiana Mudfest.

Horwitz’s apparent unfamiliarity with the Lone Star State is surprising given the enormous influence Texas has had on national politics and culture.

Held on a former plantation just outside Colfax, this annual weeklong extravaganza combines monster trucks and plein air debauchery, from heavy drinking to pole dancing on a school bus converted into a mobile strip club. Although at times Horwitz confesses to feeling like “an infiltrator,” and no doubt some readers will indict him for trafficking in a self-confessed “garish stereotype of the rural white South,” he approaches his subjects with genuine curiosity and compassion. Not so for Denton, who keeps up a mordant and hilarious commentary, at one point declaring one of the Mudfest bogs to be “God’s toilet.”

Horwitz’s equanimity is tested, however, once he crosses into Texas, at the book’s midway point (nearly half of the book is devoted to the state). At the same juncture in his journey, Olmsted and his own traveling companion, his brother John, observed, “We had entered our promised land, but the oil and honey of gladness and peace were nowhere visible.” For those nineteenth-century visitors, this unease stemmed from the sight of the grim emigrant caravans composed of determined white settlers “gone to Texas” to cash in on the cotton boom, many relying on the forced labor of their immiserated slaves.

In our time, Horwitz finds that race relations in East Texas remain particularly strained, a dynamic made plain during a stop in Crockett. At the town’s Moosehead Cafe, he talks with Joni Clonts, the friendly owner of the restaurant as well as chair of the Houston County GOP, who jokes about running off the rare liberal who dines there. (Clonts later became the town’s mayor.) Horwitz is startled by the frank racism of some of her patrons, some of whom use the N-word freely: “I wasn’t accustomed to hearing such views expressed so loudly and unapologetically, in the middle of a crowded restaurant,” he writes. Leaving Crockett after a week, he confesses to feeling as Olmsted wrote that he had upon meeting recalcitrant slaveholders early in his own sojourn: “Very melancholy” and anxiously unsure of “what is to become of us . . . this great country & this cursedly little people.”

Horwitz’s spirits seem buoyed by the prospect of the novel encounters that await once he pushes westward. While Olmsted’s ignorance of Texas was typical of Northerners at the time, Horwitz’s apparent unfamiliarity with the Lone Star State is surprising given the enormous influence Texas has had on national politics and culture—not to mention that authors like Gail Collins and Lawrence Wright have recently written high-profile books (cited in Horwitz’s bibliography) attempting to explain Texas to outsiders. This inexperience leads Horwitz to discoveries that will come as no surprise to virtually any Texan or even visitors who have traveled around the state: Houston is indeed one of the nation’s most diverse cities and has some of the country’s worst traffic; the Rio Grande borderlands are, in fact, a land apart, home to a unique blending of U.S. and Mexican cultures; the state capital, despite its natural beauty and live-music scene, lost the battle to “Keep Austin Weird” years ago; and, yes, the Alamo is small. Likewise, many Texans love God and guns in equal measure; Buc-ee’s—with its dozens of fuel pumps and acres of merchandise—beggars belief; and live oaks are craggy and majestic. In short, up to this point Horwitz’s observations break little new ground.

But Horwitz digs into fresher soil once he reaches the Hill Country. Most Texans are aware that the long history of German immigration to the state did not begin in 1998 when the Dallas Mavericks acquired Dirk Nowitzki. Yet fewer probably know that in the mid-nineteenth century many German communities were “a sanctuary for Socialists, utopians, and adherents of heterodox faiths from abroad,” as Horwitz explains.

Olmsted fell in love with places like New Braunfels and Sisterdale. At first he was simply happy to be among educated people who shared his tastes and values, in one of the prettiest parts of the state. These hamlets flourished in the years after the failed European revolutions of 1848, attracting groups like the Deutscher Freidenker—German freethinkers—who championed reason and eschewed religious dogma. Even more meaningful to Olm-sted was their apparent commitment to the anti-slavery movement, which he too had come to ardently embrace, thanks to his travels throughout the South. In short, as Horwitz puts it, “Yeoman had found his Arcadia: an agrarian domain of ‘unsurpassed’ beauty, honest labor, and intellectual and artistic refinement.”

Horwitz, though, finds less to admire. For one thing, arriving in New Braunfels he writes that “the compact, country town of Olmsted’s day had metastasized into a bedroom community of sixty-five thousand strung along the interstate corridor.” For another, he is also put off by the relentless assault of “German heritage embalmed in kitschy commercialism,” captured in a marketing slogan emblazoned on a billboard: “Sprechen sie Fun? ”

But most unsettling is his discovery, thanks to a walk-through of the town’s Sophienburg Museum and a conversation with one of its staff members, that Olmsted had misunderstood or exaggerated the Germans’ supposed aversion to slavery. Rather, he learns that—notwithstanding the principled resistance of some Germans, like those who perished in the Nueces Massacre of 1862—their communities viewed the peculiar institution as impractical more than repellent, given the small size of their landholdings, as well as their conviction that a job well done required that they—not slaves—do it.

Gradually, German immigrants and their descendants found common ground with their Texan neighbors; by the time of Horwitz’s visit, these communities had left behind their progressive tendencies and become deeply religious and solidly red. Instead of experiencing Olmstedian elation, Horwitz struggles with gloom (and indigestion, thanks to a heaping Wurstplatte).

His Hill Country sojourn goes from disappointing to disastrous when he resolves to see the countryside around Sisterdale just as Olmsted had—from the saddle—resulting in the book’s funniest and most poignant chapter. The journey is doomed from the start. While Olmsted rode a horse, Horwitz has a mule named Hatcher, who is, predictably, quite stubborn. Worse, though, is the truculent guide whom Horwitz calls “Buck” in order to preserve his anonymity. While “as ruggedly handsome as the natural surrounds,” Buck resembles an abusive parent for whom no job is done well enough, whether the task at hand is fording a river, setting up camp, or just tying a knot.

Buck’s tirades lead Horwitz’s travel companion during this part of the journey, a local named Josh Cravey, to quit mid-trip, and Horwitz suffers a concussion when he and Hatcher literally butt heads. Piling insult atop injury, Buck shouts at Horwitz: “I’ve never seen anyone in my life with so little common sense!” For Horwitz, “What stung much more was my failure in a department of which I’d felt I was chair: finding a way to reach and get along with just about anybody.” Back in Sisterdale, another local explains the breakdown this way: “[Buck] needed to put your East Coast writer’s ass in its place.”

In the end, Olmsted’s time in Texas strengthened his anti-slavery leanings, convincing him beyond doubt that the practice of bondage had hampered the state’s development despite the extraordinary advantages conferred by a mild climate and fertile land. As such, he threw in his lot with those who opposed the expansion of slavery into the West, striking a defiant tone that suggested he welcomed a fight with the other side.

For his part, Horwitz ends up deflated by his Texas trek, since he finds the battle lines between red and blue drawn with razor sharpness. He insists that this polarization is not just the fault of Republicans, taking to task his glib “New England neighbors” who regard Texas as “arid, alien, and hostile, like ISIS-controlled parts of Syria.” Horwitz himself now knows better. And his discussion of our current politics suggests that he also knows—as Olmsted surely did in the late 1850s—that the next presidential election will be uncommonly bitter and consequential. Presumably, he will be following the results from the safe distance of Massachusetts.

Andrew R. Graybill is the chair of the History Department at Southern Methodist University and the author of The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- New Braunfels