Before brisket dominated Texas barbecue, meat markets served a vast variety of smoked beef cuts. The old-school meat markets of Central Texas would smoke anything left in the case too long, most often cuts from the forequarter, like shoulder clod or beef chuck. In the Dallas area during the forties and fifties, smoked beef typically came from a little further back on the steer, specifically beef plate, a.k.a. beef navel, a.k.a. navel plate.

Billy McDonald runs Mac’s BBQ on Main Street in Dallas, a barbecue joint started by his father more than sixty years ago. “Back in the fifties when I was a kid sitting on the wood pile at my dad’s barbecue place down there at 3600 Main, you didn’t have briskets. It was navel plate ends or clods,” McDonald told me. They also didn’t serve it sliced. Barbecue meant a chopped beef sandwich, or some other smoked meat on a bun, as McDonald recalls. “When he opened up at Main Street, he had navel plate ends, he had Farmland cured canned hams, and he had Rudolph’s sausage. Those are the three meats he carried.”

Roland Lindsey founded the Bodacious Bar-B-Q chain in East Texas, but before that he had a little shop of his own in Duncanville (just south of Dallas) in the late fifties. He, too remembers cooking those giant beef plates. “I didn’t see a brisket for years,” he recalled. As for the beef plates, “We’d use a mop to put the gravy on it. We’d serve it on white bread for a long time. In about 1964 I started to use buns. We’d put the beef and gravy on there. At the end of the day it would all get cooked down and get real rich. It was good.” (He referred to that gravy as “Arkansas gravy–mostly water with a little sugar, salt, a little Worcestershire, and a little tomato sauce.”) As McDonald remembers, they didn’t start off by offering white bread at Mac’s Bar-B-Que. “We would use white buns or square rye bread.” But the condiments were important. “You always had pickles, relish, and onions,” just as McDonald–and most other Texas barbecue joints– offer today.

What is a beef plate? It comes from the center of the steer just below the ribeye. In fact, when the rib primal is separated from the carcass, the lower portion of those ribs that remains is the beef plate, also called the beef short plate. It’s IMPS item #121, and is rarely sold intact these days. Included in the cut is the outside skirt steak, inside skirt steak, beef belly, and the beef plate short ribs. That’s right, in Dallas they were eating smoked beef short ribs (albeit chopped along with everything else) long before it was cool.

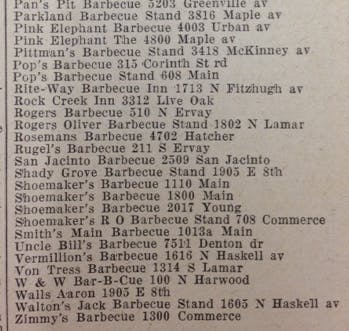

Gary Williams owned Gary’s Barbeque in Amarillo for decades, but worked at a few other barbecue joints before then. He started at Dub’s in downtown where they cooked beef plates. When I interviewed him recently, I was curious how Dallas and Amarillo shared such similar barbecue traditions. He told me, “They had started in the forties. They were trained by Shoemaker’s, in Dallas. There were two guys who learned from them and came back here. It was Dub and Bingo.” Dub, of course, owned Dub’s, and the spin-offs from that included the now-shuttered Gary’s Barbeque, along with Doug’s Bar-B-Q and Henk’s Bar-B-Que, which are both still in operation. They all cook brisket now, but back then they cooked the same beef plates that Dub cooked and everything was served on a bun. They didn’t serve barbecue plates with options for meats and sides like they do today. The other guy, Bingo, went off to Lubbock to help start Tom & Bingo’s Bar-B-Q. They cooked clods for a time, but today, a sandwich is still all you can order at Tom & Bingo’s. It’s kinda like eating barbecue in Dallas sixty years ago.

Back then there were four locations of Shoemaker’s Barbecue. They were all run by a family member, and from the addresses I found in an 1947-48 Dallas directory, it was hard to pass through downtown Dallas without bumping into one. Roland Lindsey said he enjoyed their barbecue when he lived in Dallas. I couldn’t find much on the family, but the demolition of the R.O. Shoemaker Barbecue Stand at 708 Commerce was news enough to warrant a mention from Texas Monthly in 1974.

James Earl Shoemaker passed away late last year, but the Shoemaker style lives on as far away as San Diego. The Barbecue Pit restaurant was started in 1947 by Joe and Lila Browning and Ed and Mela Jenson. They claim a strong tie to Dallas on their website, which says, “Joe came from Texas where he learned the barbecue business from his step-father, R.T. Shoemaker. R.T. owned several barbecue restaurants in the Dallas area called ‘Shoemaker’s Famous Barbecue’.” Alas, there’s no beef navel on the menu.

Williams loved the fatty beef from the navel, and he described how one would tackle it on the cutting block.

“In the morning you’d get one on the block and remove the big fat cap. You’d peel that off and underneath was about an inch of butter fat. Yummy, yummy. There was also a thin membrane like elastic, so you’d run your knife down and get all that out of there. Then you were ready to go.”

Billy McDonald also recounted the struggle of cooking a whole beef plate. “You have to understand, this piece of meat was huge. About a third of it was bone. You had to cook it one day to pre-cook it. Then you’d flip it over and take a paring knife and cut away the bone and strapping out before you could finish cooking it.”

And flipping a whole beef plate wasn’t an easy job, as McDonald remembers. “[My dad] cooked four plates a day. That took up the whole pit. These things weighed probably forty or forty-five pounds.”

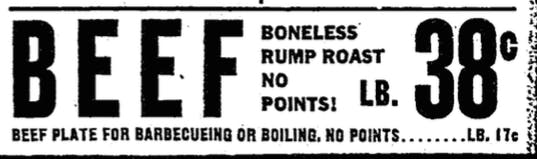

All that waste went to good use back then. In Dallas there was money to be made from the Valcar Rendering Plant who would come pick up the waste and pay a fee for it. McDonald remembers separate barrels for the different levels of waste. Grease was drained out of the pit into a barrel. Another barrel held the bones, and a third barrel captured anything else that was left on the board. “Valcar, they would buy your grease and your bone scraps. The bone scraps would be ground and made into rosebed fertilizer.” Every little bit helped even though the beef was dirt cheap at the time. Even as late as 1964, there were ads for $0.17/lb navel end plates when brisket cost $0.53/lb. McDonald said there just wasn’t a huge demand for it. “It was pretty good meat, but they had no market for it except for hot dogs.” But then the prices started to raise, and brisket remained cheap. Once boneless brisket was available by the box, it replaced beef navel on the menu at Mac’s Bar-B-Que in the mid-sixties, and pretty quickly became the de facto protein across the state. Beef navel hasn’t seen the inside of a smoker in Dallas since…2015.

Don’t call it a comeback, but while I was researching this story, two barbecue joints in Dallas advertised a new special on their menus. Lockhart Smokehouse in Plano and Cattleack Barbecue in Dallas were smoking beef belly, a cut from the beef plate just below the short ribs. It’s a fatty cut, but they were serving it sliced anyway. Cattleack’s version was beefy with thick ribbons of fat. I tried it next to slices of fatty and lean brisket, both of which I preferred to the unadorned beef belly.

At Lockhart Smokehouse the fatty cut struggled to maintain its shape in the grease soaked butcher paper. A bite of the rich beef seemed decadent. Sold by the half pound, I couldn’t imagine how my gut would react if I finished a full order, but then I remembered how it was enjoyed by so many Dallasites before me. I grabbed a couple slices of white bread and topped it with the remaining beef which I had chopped along with some pickles and red onions (see photo at the top of this post). It was at once soft and crunchy, heavy but crisp. The acidic pickles and stout onions cut the richness of the beef considerably, but the fat soaked into the bread like melted butter. This was a sandwich to savor, and I did. It felt like I was consuming a long-forgotten piece of Dallas history, but it also made for a delicious lunch.