This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The young man in his thirties, wearing a pink knit shirt with brown pockets, parked his maroon and chrome pickup on the shoulder of Farm to Market Road 1418 some three miles east of Falfurrias. His wife stepped down from the pickup and joined him inside the gate to the chain link fence that surrounded the ten-plot cemetery. She wore polyester shorts and a cotton blouse, and she carried a votive candle.

Hand in hand, the couple entered a small concrete-block building in the corner of the cemetery and knelt at the altar inside. They made the sign of the cross—Mexican style, kissing the thumb and forefinger at the end of the gesture—and in quiet voices began to pray. In the name of God and Don Pedrito Jaramillo, Juan and Julieta asked for success in childbirth, or perhaps the recovery of an ailing friend, or the elevation of a relative’s soul to heaven.

Pedro Jaramillo, a thin, bearded man with the omniscient stare of a Yoda or Meher Baba, died at Falfurrias in 1907. He was 77. He left no widow, no descendants, no endowments. But within days of his death, admirers searching for potent talismans sacked his hut of all his personal belongings. Today, so little is known about Jaramillo’s life that even his matronymic is lost. Yet Don Pedrito is revered as no other Texan is.

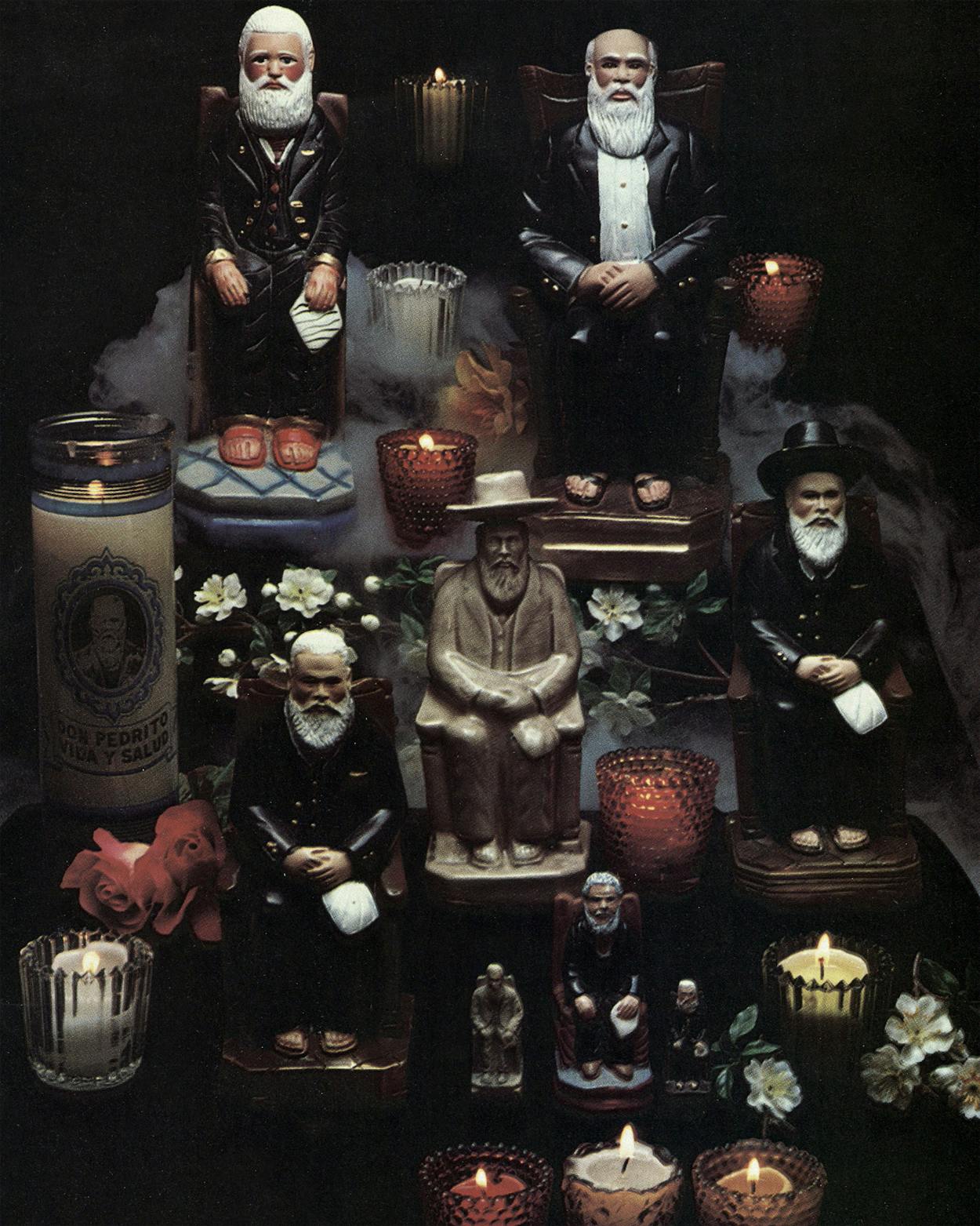

In Juan and Julieta’s house and in thousands of homes across South Texas, painted plaster of paris statues of Don Pedrito sit on family altars next to the Virgin of Guadalupe or Our Lady of San Juan of the Lakes. Candles bearing his image are sold in grocery stores across the state, and in the Valley, medallions, prayer cards, incense powders, and oils labeled with his name are the daily stock-in-trade of a hundred yerberías, or herb shops. Over much of Texas, and especially in the south, Don Pedro is regarded as a saint. The Catholic Church has not yet been handed petitions for his canonization, but it accepts Don Pedro, too. All souls in heaven are saints, and prayers may be said through them. The cult of Don Pedrito Jaramillo fits comfortably into Church doctrine, linking native traditions to a far-off Vatican.

Jaramillo’s advent was timely. In 1881, when Don Pedro, then in his fifties, came from Mexico to the Los Olmos Ranch near Falfurrias, both savers of the body and savers of the soul were in short supply in South Texas. Only one doctor lived in the region between Corpus Christi, San Antonio, and the Rio Grande, and much of the Catholic ministry was in the hands of horseback itinerants. Don Pedro filled the gap as only a curandero, or cure maker, could have.

A curandero is a folk doctor, priest, attorney, and psychologist. Licensed medical, religious, and legal specialists dispense contemporary wisdom; curanderos deal in indigenous New World mysticism, mixed at times with bits of hocus-pocus from the days of conquistadors and colonists. In the eyes of conventional doctors, curanderos are quacks at worst, practitioners of bedside manners at best. The strong suit of curanderismo, and the Achilles’ heel of the organized professions, is that the curandero or curandera—for many healers are women—is a sympathetic soul who has time to listen. Unlike their licensed counterparts, curanderos accept gratuities but do not charge fees.

Curanderismo in its simplest form is household herbalism: mothers in traditional Valley homes are expected to alleviate colds and croup and cases of mal ojo, or evil eye, in the same way their grandmothers did. Stomachaches are abated with sweet basil tea, and susto (an ailment thought to arise from fright or shock) is treated with a regimen that includes both Hail Marys and body sweepings with a whole, unboiled egg. Supplies for herbal cures are dispensed in dozens of borderland yerberías and botánicas. However, few herbs in use today have any medical significance, and herbalism as a science became obsolete when it was replaced by modern synthetic pharmaceuticals.

Curanderismo has survived despite medical progress because faith cures do occasionally work, because physicians are sometimes inaccessible, and because most curanderos also practice the occult arts. Using the forty-card Mexican tarot deck, colored stones, magical sands, invocations, candles, and incense, they conjure up predictions and solutions for business and personal problems. They also cast spells. One consequence is that South Texas is periodically pocked with bitter duels in which curanderos call down bad luck, ill health, or even death upon one another or upon enemies of their clients.

If supplicants like Juan and Julieta are not content with a simple prayer said in Don Pedrito’s name, they may turn to one of the dozens of living curanderos who offer to put clients in touch with spirits of the dead, including that of Don Pedrito himself. Spiritism, though contrary to Catholic belief, is the current curanderismo vogue. In shamans’ sheds across the Valley, mediums in trances voice advice and prescriptions from Don Pedro. His communications, they say, are brief, brusque, businesslike, even abusive; Don Pedro in spiritist apparition is the same paternal but irritable soul who presided in the flesh at Los Olmos. According to a legend, Don Pedrito prescribed that a woman afflicted with migraine headaches have her head cut off and thrown to the hogs. The advice infuriated its recipient, who—after a bout of reddening rage at Don Pedro—never again suffered a migraine. On some occasions Don Pedro refused to prescribe for patients, telling them they had too little faith to make any cure work, and at other times he told them that their ailments did them more good than harm.

Don Pedro was not an ordinary curandero by the standards of his time or ours. He declined to counsel clients about romantic or business affairs, did not tell fortunes, and would not pronounce curses himself or rescind those cast by others, because, he told one supplicant, he did not want to earn the enmity of other curanderos. Unlike his heirs, he apparently believed that those who put faith in magic merited the misfortunes conjured up by like-minded men.

Though he sometimes prescribed herbal remedies, Don Pedro suspected that their greatest power was that of suggestion. An oral legend tells of a Falfurrias grocer who, while chatting with Don Pedro, bemoaned a stockroom oversupplied with canned tomatoes. For the next two weeks, the legend says, Don Pedro told his supplicants that in order to cure themselves they need only put faith in God—and bathe with canned tomatoes. Jesus used only three substances to heal—water, mud, and spittle—and Don Pedro emulated His method. Don Pedro’s most frequent prescriptions for any ailment required no herbs at all: three or nine baths, or three or nine glasses of water. Like Jesus, Don Pedrito explained his healing powers by telling cured patients: “Your faith has made you whole.”

According to several myths, Don Pedro had parapsychological abilities. In one story, a pair of murderous doubters invited him to drink. Before downing the glass of wine they offered him, Don Pedro warned them that he knew it was poisoned and that he would turn the occasion into a proof of his powers. He suffered no ill effects after drinking the poisoned wine, but the doubters were immediately stricken with stomach cramps. In another instance, Don Pedro is said to have told a doubter, “I am as certain of my prescription as I am certain that you are wearing borrowed shoes.” The doubter, who was sitting across a table from Don Pedro, was wearing borrowed shoes.

Both written and oral reports indicate that Jaramillo was subject to psychic storms similar to the mystical moods of Muhammad, Jesus, and Joan of Arc, not to mention schizophrenics. Don Pedro frequently was seen talking and gesturing while walking or riding alone. In 1899 he wrote a letter urging his followers to “do penance of your sins without pomp . . . venerate the Sacred Church and its images . . . pray Mary’s Holy Rosary . . . for on the contrary I will make the earth open and swallow everyone.” At the bottom of his epistle, he wrote the words “transcribed by Don Pedrito Jaramillo,” as if his hand had merely taken a message dictated from above. However, there is no evidence in document or legend that Don Pedrito, a resolute Catholic and a dutiful contributor—in 1903 he bought the bell for the Falfurrias parish church—believed in spiritism or would attend any séance, even one held in his name.

In April 1894, after his renown had spread throughout the region, Don Pedrito visited San Antonio. At the end of his mission there, a reporter for the Express wrote, “Whatever Don Pedrito may or may not be—and nobody seems to know—he kicked up more high jinks during his stay of one month than any one quiet individual who ever entered the city limits of San Antonio. Whether he cured people or not is for some of the thousands to say who went to see him.” Other than the brief Express accounts of his San Antonio circuit, no contemporary record of Don Pedro’s life and work has been found. The man who is worshiped at the cemetery in Falfurrias and across South Texas is part family remembrance, part oral legend, and part creation of his curandero heirs.

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics