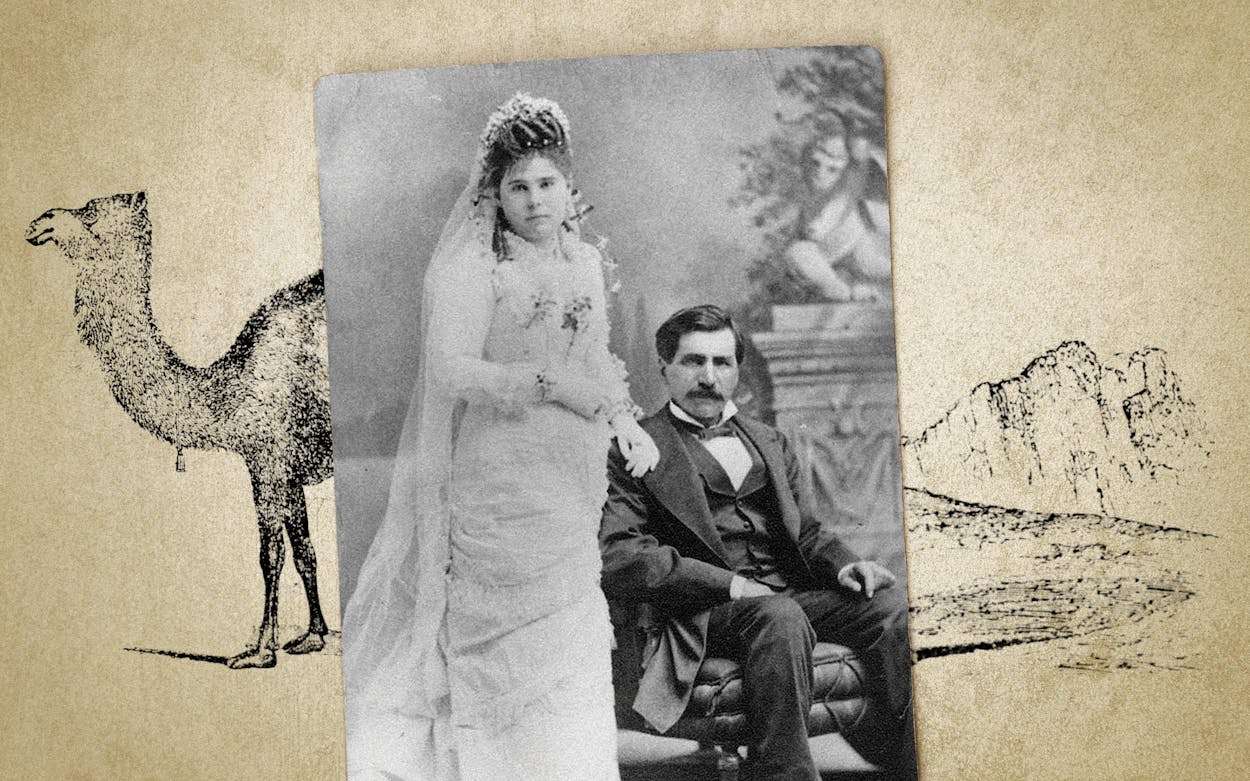

In 1856, Hadji Ali—one of the first documented immigrants from the Middle East to the United States—was recruited by American soldiers and brought to Indianola, along the coast between Galveston and Corpus Christi, to lead a herd of camels along the unforgiving trails of the West. He traveled alongside Navy Lieutenant Edward Beale through New Mexico to California, as part of a project dubbed the United States Camel Corps—an effort that was ultimately abandoned, but not before the duo made progress that became part of the iconic Route 66. Ali, often pictured wearing western clothing, spent the rest of his life in the United States.

Laith Majali, a Los Angeles–based Jordanian photographer, told me he was drawn to this man who was pulled from the Arab-speaking world to “the deserts of America” to assist in the nation’s westward expansion. Majali, whose photo series “On the Trail of Hi Jolly” recounts this journey through the American Southwest, said Ali’s experience of navigating the unknown resonates with his own story of immigration. And it’s one in which I can see reflections of my own.

Like Ali—commonly referred to as “Hi Jolly” because it was easier to pronounce for Americans—my name has also taken on a watered-down pronunciation; “Saliha” sounds closer to “Selena” than its original Arabic sound when flowing from a native English speaker’s tongue. I grew up in Massachusetts, where my Muslim and Turkish identity wasn’t always well received; when I started wearing the hijab in middle school, I took on nicknames such as “towelhead” without putting up much of a fight. When I moved to Texas this past summer, I expected I’d have to hide parts of myself again; the mythos of the state as a wild west, hostile to outsiders, persists in the Northeast.

Some of that perception is warranted: Governor Greg Abbott has long opposed the resettlement of refugees in Texas—notably Syrian refugees following the 2015 terror attacks in Paris—and he announced in 2020 the state would opt out of the resettlement program. (Despite this, Texas still resettles more refugees than any other state in the U.S.) Growing up, I knew Texas only through election maps, as a sea of red with small blots of blue. I had expected I would come across small-town, conservative Texans who were unfamiliar with my culture; I feared they would hate people like me. Orientalism-fueled false narratives have long been perpetuated about people of Middle Eastern heritage: that we are backward, barbaric, and unable to blend into American society. But I had also absorbed flawed stereotypes about Texans, and it wasn’t until I lived there that I discovered the long history of Middle Eastern influences in this massive—and massively diverse—state.

Ali’s ethnicity is debated, but he was most likely a Bedouin man from the Ottoman empire—though he was not the first man from the Middle East or North Africa region to come to America. That was Mustafa Zemmouri, or “Estevanico,” a Moroccan Berber slave who was part of an ill-fated Spanish expedition that washed ashore in present-day Galveston Island in 1528. Centuries later, between the 1870 and 1930, an estimated 300,000 people emigrated from the “Greater Syria” area—which includes modern-day Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria—and around 1,600 eventually settled in Texas. By 1920, there were more than 3,200 Arabic-speaking immigrants and their families in Texas.

It was during this time that Fred Kadane, a Syrian immigrant, and his brother George arrived in Denison, along the present-day Oklahoma–Texas border, from his original point of arrival in New York to invest in the oil industry. He wrote that he was shocked at the scene in the “little Texas town,” with cowboys, saloons, gambling houses, Texas lingo, and wild horses. Initially resistant to this new environment, Kadane grew to love Texas, finding success in multiple business ventures and planting roots. But still, there was persistent hostility; early immigrants from Greater Syria were considered nonwhite and faced assaults and discrimination. In 1922, Kadane lost the grocery store that he had opened in Wichita Falls to the Ku Klux Klan, who forced him to sell the grocery for one-fourteenth of its value.

From news accounts at the time, it’s clear that the Syrian community in the U.S. held tightly to the conviction that they could both be proud of their heritage and leave their mark on what was once unfamiliar American land. “But we Syrians, as well as other races who are not classed among the so-called Nordics, want to prove that we are a valuable element in the composition of the American nation,” wrote Salloum A. Mokarzel, editor of New York–based the Syrian World, in 1928, during a time when Syrian clubs were emerging in Texas and across the country.

That early influence of Middle Eastern immigrants on the American Southwest is still apparent if you look closely. Sama’an Ashrawi grew up in the nineties in Cypress, which was at the time a smaller suburb of Houston comprising farmland, horse stables, and pickup trucks. It’s a town where a loose cow literally crashed a party Ashrawi attended in high school. So it’s no surprise that Ashrawi, who is a proud Palestinian, fashions himself as an “Arab Cowboy.”

When I ask Ashrawi, a storyteller (and Texas Monthly contributor) with a love for music writing, where he thinks Palestinian and Arab culture overlap with that of the American Southwest, he points to the music. Many of the musical scales characteristic of blues and jazz are influenced by Arabic music, a crossover that originates from the folk music created by the early enslaved Africans brought to America from Muslim nations. Ashrawi himself produced a rendition of the blues classic “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” which features vocals from Kam Franklin over an oud instrumental played by Kareem Samara, creating a track of solidarity.

During my stint in the state’s capital, I’d often drive by the Arab Cowboy hookah lounge, owned by “a boy from Tunisia” and “a girl from Kansas.” On my last day in Austin, I finally stopped in. It’s a place Ashrawi would frequent while attending the University of Texas, sometimes to study and sometimes just to smoke hookah. On my visit, I walked through a cloud of smoke, a scene and smell that unmistakably reminded me of Turkey. A young woman in a blue hijab worked on her laptop, while couples in casual clothes slouched on the couches, lost in conversation.

In and around Austin, I could see the impact of the Middle Eastern diaspora everywhere. The Lebanese-American Antone family made their mark in and around downtown with Antone’s Nightclub, Antone’s Record Shop, and their po’ boy grinders. Tacos al pastor, an adaptation of meat preparation by Lebanese shepherds in Mexico, is a dish I saw everywhere. And across the state, restaurants serving classic Southern dishes, such as Ricky’s Hot Chicken in Dallas, have decided to use halal meat to make their dishes more accessible to the Middle Eastern Muslim community.

I never once felt out of place in Texas. That assumption I’d arrived with—that the South is hostile and the Northeast is tolerant—doesn’t reflect my reality.

The idea was born in part from a restrictive two-party political system that pits people with seemingly irreconcilable differences against each other. Dr. Husam Omar, who researched immigrant entrepreneurs in Laredo for many years as a visiting professor at Texas A&M International University, noted that regional and individual attitudes differ widely in Texas. He told me that Arab Americans in Laredo, where many of these first Syrian immigrants settled, today hold esteemed roles in the community as business leaders, lawyers, and politicians. But in some places, an outward display of one’s Middle Eastern culture is still met with hostility. In order to curb this, we must stop “politicians who capitalize on divisions,” Omar told me. “It’s like a storm that is gaining strength.”

Despite that storm, a real sense of solidarity exists among residents in many areas of the state, even in some parts of rural Texas. Amarillo, for example, home to the tristate rodeo and Big Texan Steak Ranch, also boasts the growing Islamic Center of Amarillo. The city of 200,000 mostly white and Christian residents has welcomed refugees from countries like Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Myanmar, and, most recently, Afghanistan. It now has the largest density of refugees per capita in the state—there were 256 refugees for every 100,000 residents in 2014. Paul Harpole, who was mayor of the city from 2011 to 2017, expressed his support for the refugees, along with his concern that the influx was overwhelming the city—an attitude shared by many Amarillo residents. But Ginger Nelson, the current mayor of Amarillo, retains a positive attitude toward the newcomers, and many residents have welcomed them with open arms. Amarillo-based nonprofits, like Catholic Charities of the Texas Panhandle, help resettle and accommodate thousands in the small city.

Although some Texans are continuing to come to terms with it, we are not strangers at odds, but people with a shared history who have triumphed over unfamiliarity before. I came back to Massachusetts with a pair of old cowboy boots and a new understanding of Texas—the culture of the American Southwest is not incompatible with my own Middle Eastern heritage, and it requires no compromise.