On a stretch of highway between Concepcion and Premont, less than a mile from the unremarkable intersection of FM Road 716 and FM Road 1329, a miracle is growing. On any given afternoon, hundreds of cars and trucks blow past this spot, about a ninety-minute drive east of Laredo. But sometimes people feel compelled to slow down. Some say it was an angel, or even Jesus Christ, who appeared on the road and called them to pull off and park in front of a chain-link gate, where hundreds of rosaries clink against the metal in the breeze. Others, like me, seek this spot out, hoping to find the tree that Estella P. Garcia planted in 2002.

I set out for the tree in late November. Absent any major landmarks nearby, I can’t tell if I’m even driving in the right direction. Reception is spotty, but Garcia’s daughters, Estela Garcia Cantu and Gloria Garcia, are trying to guide me there by phone. “If you look up at the tree line, you won’t be able to miss it,” Cantu tells me. “It’s a good thirty feet taller than any of the trees nearby.”

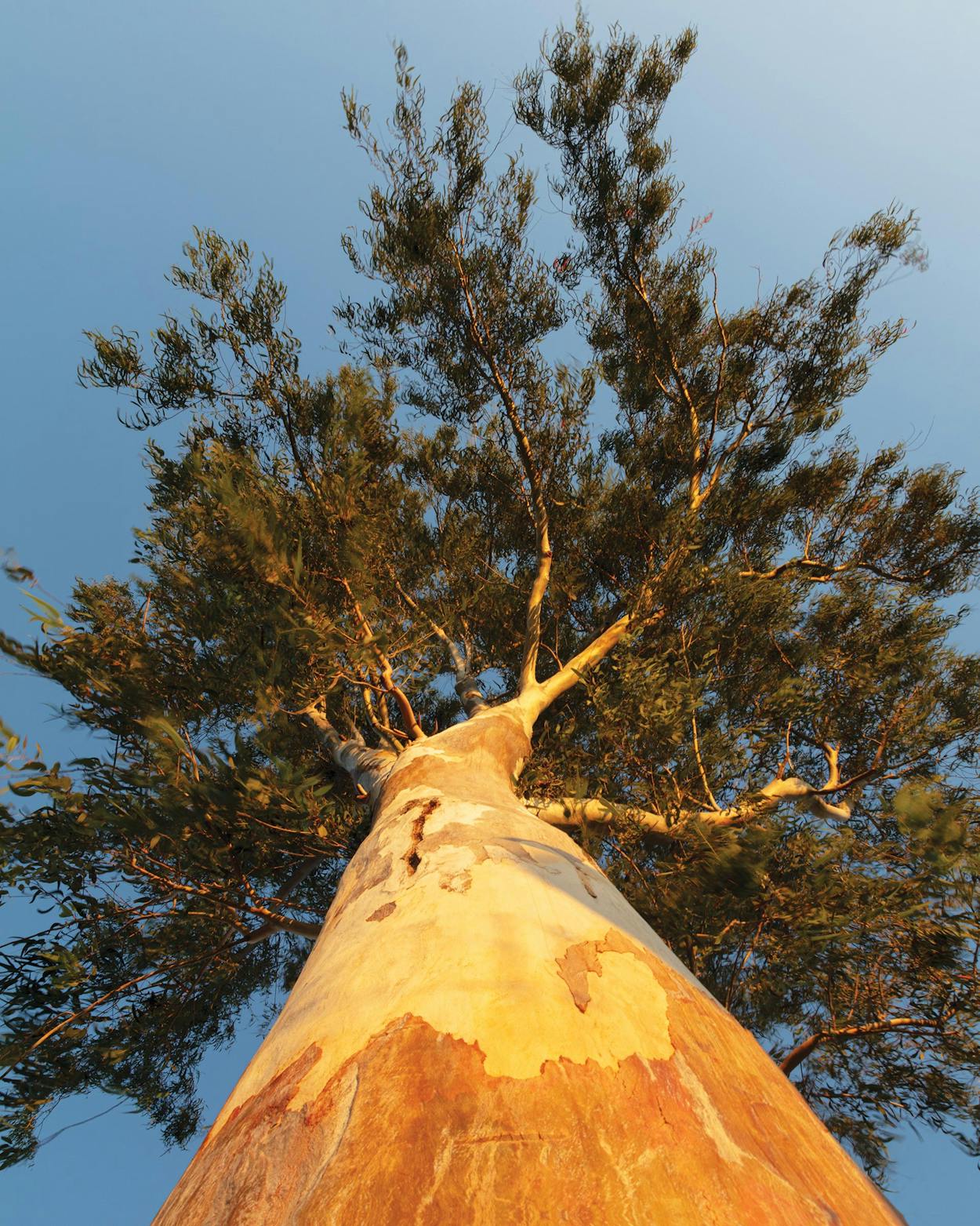

Soon I spot its leafy crown standing out against the miles of brush and ranchland. I follow the road toward it until I see Cantu waiting for me in the driveway of her mother’s one-story yellow clapboard house. Gloria is seated on a bench nearby, between the house and a white portable building resting on cinder blocks that serves as a chapel. After the sisters introduce themselves, Cantu wastes no time taking me to the tree. The bark on its narrow trunk is peeling, revealing pale splotches. The spindly branches near the top are a ghostly white. They don’t fan out; they reach straight up toward the sky.

“Look at the leaves,” Cantu instructs me, pointing up at the narrow, lance-shaped fronds hanging from the branches. “You won’t find trees like this here.”

“A lot of people ask if we water it,” Gloria chimes in. “It’s never watered, but you can see how wet the soil is.”

“It just survives on what the Lord sends us,” says Cantu.

Like a Rorschach test, Garcia’s tree appears differently to every visitor, shifting to accommodate each individual’s prayers. One lost soul might take comfort in finding the Virgin Mary’s face hidden in the tree’s bark; another visitor might feel physical relief when she holds her injured limb against its smooth, cool trunk.

Penitents think the tree is godly; it is also the product of Estella Garcia’s force of will.

Garcia grew up in Concepcion, which is home to the oldest Catholic church in the region and fewer than one hundred residents. One of six siblings, she was deeply religious throughout her life, going to church every Sunday and studying her Bible often. She retired from her job as a restaurant chef in 1986, when she was fifty years old. Since her children had left the house—and especially after her husband’s death in 1997—she was always looking for ways to keep busy. She sold fruits and vegetables around town for extra money, she picked up groceries for neighbors and family members, and she cooked for anyone who stopped by.

In 2002, Garcia found a new project. In both Testaments of the Bible she’d read about the Mount of Olives, a ridge just east of Jerusalem’s Old City that was once covered by olive trees. The site has been a sacred place for centuries, and Garcia was determined to find and plant a tree descended from those growing there. She found a nursery in the Rio Grande Valley that would sell her a cutting, but was told that it might take a while to arrive. She was happy to wait. The tree was going to be a place for miracles—a site for those with physical and mental maladies to mend—and you don’t rush miracles.

Months later, someone from the nursery called. Garcia set out for the Valley and returned with an eighteen-inch cutting of what she was certain was an olive tree. (After I left the sisters, puzzled by some of the tree’s unique characteristics, I described it over the phone to Patrick Brewer, a tree-care specialist based in Austin. We discussed its height, and he noted its peeling bark. “Sounds like a euc to me,” he said. I called Cantu shortly after the conversation with Brewer, terrified that I was about to spoil the tree’s magic. When I pointed out qualities that are abnormal for an olive, but standard for a eucalyptus, she laughed and said, “A lot of people say that it reminds them of a eucalyptus. Regardless of whether it’s an olive or not, this is the tree my mom prayed for.”)

Garcia put the cutting in the ground and began to pray. After six months, it had sprung up six feet. By the following year, it was nearly eighteen feet tall. Every day, for years, Garcia sat near the tree, asking God to keep the tree healthy. Now it towers over her house.

Gloria was living and working in Nashville in the years after Garcia planted it. “She called me to tell me about the tree and I was like, ‘Yeah right,’ ” she says, laughing.

“My mother had us all going,” says Cantu. Still, she adds, “we were all skeptical.”

In 2004, the sisters tell me, Garcia was running an errand in nearby Falfurrias when she struck up a conversation with a stranger and his wife. She made friends wherever she went, her daughters recall; within a few minutes, the man had confided in her about an upcoming knee surgery. Garcia suggested he and his wife follow her back to her home, where, she said, she had planted a miracle tree. She prayed over the man as he knelt at its base. Later that week he visited again, to tell Garcia that his doctors had said he no longer needed the surgery. To repay her, he built a tin roof over her patio, so she could sit in the shade while she prayed.

After that, the sisters say, more visitors began finding their way to the tree, through word of mouth and local news reports. A front-page article published in the Duval County Picture in October 2007 reads, “A tree believed to possess the power to heal continues to draw hundreds of people a week to see what they believe is God’s healing power.”

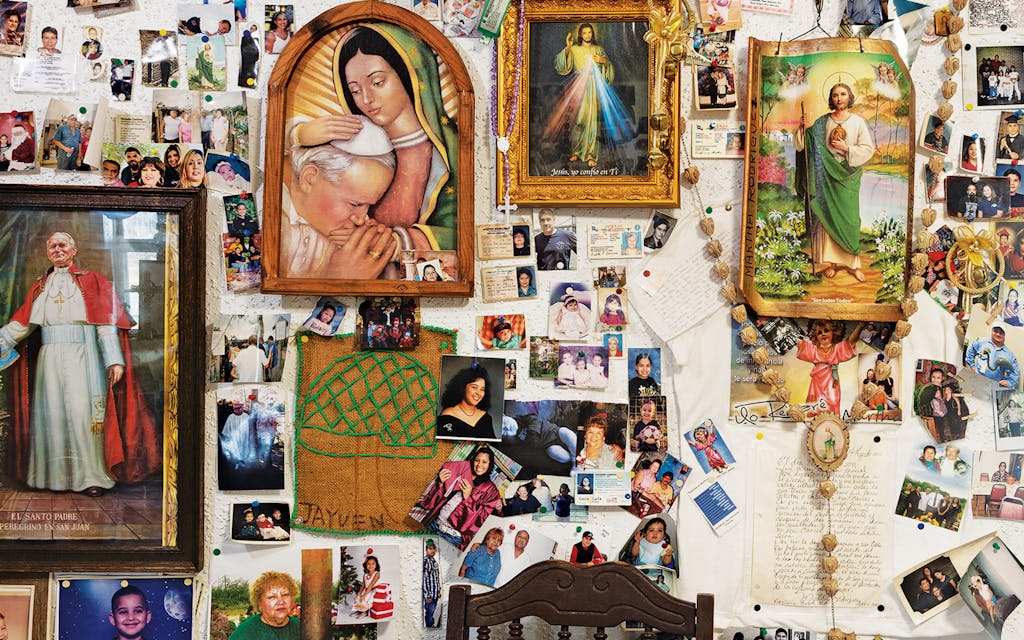

These days, the walls inside the chapel in the yard are covered in photos, notes, and newspaper clippings, most recounting miracles that visitors say happened here. The ceilings are low and the room is dim. It is silent apart from the sound of an oscillating fan in the corner. Bottles of oil infused with leaves from the tree are displayed on a table. Cantu accepts donations in exchange for the bottles, which go toward the property’s upkeep; she also gives the oil away for free.

Over the years, Cantu has compiled hundreds of letters in a black plastic binder. In one note, written in neat cursive and dated 2006, a woman whose sister brought her leaves from the tree, which she believed helped her recover from a stroke, thanks the Lord. In another, scrawled in blue ink and torn out of a spiral notebook, a woman shares that after another visitor prayed over her at the tree, the complications she had suffered during pregnancy vanished, and she gave birth to a healthy son. “I remember it was cold,” she wrote of the day of her pilgrimage. “I put my belly next to the tree and asked God to heal my baby. As I stood there I could hear water running through the tree. I felt that everything would be okay.”

For hours Garcia’s daughters regale me with stories of the hopefuls who had traveled to the tree—stories that made believers out of both of them. “I was one of those people who doubted the tree, but there’s been so many things that have happened to me or to our family that are unexplainable,” says Gloria. “We’ve had miracles of our own,” Cantu agrees.

In 2017 Garcia asked her daughters to locate her grandson, Cory Garcia, who was estranged from his father, Garcia’s son Marin Jr., and from the rest of the family. They hadn’t seen or heard from Cory since 1979, when he was four years old. They only had a handful of papers he’d scrawled on and a few photos of him as a young boy.

The sisters checked genealogy websites, hitting dead ends until they discovered a man who appeared to be a possible match. He lived in Collinsville, Illinois, across the river from St. Louis, Missouri. He was the right age, and he bore a resemblance to Marin Jr. Cantu’s daughter April contacted him on Facebook, telling Cory that he had family in Texas who were looking for him. Initially he feared it was a scam.

But when Cantu sent him the messages he’d written to his grandmother as a child and photos of him with his father, he asked to speak with her immediately. Over a two-hour conversation, they pieced his life together—from his parents’ separation to his move from Texas to Illinois. He’d grown up believing that his mother didn’t know who his father was. He’d thought he didn’t have any extended family.

Cory asked to see a photo of his grandmother, and when Cantu sent one he was startled. He tells me over the phone that at the end of June 2018, he started having dreams about a stranger several times a week. “There was this lady with bright red cheeks standing in a graveyard near a tree. When I got that picture from April, I realized that lady in my dreams was my grandma.”

When Cantu and Gloria reached out to him, Cory was battling an infection in his foot from a diabetic ulcer. He’d spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on surgeries and exams and was exhausted by the never-ending doctor’s visits—the wound from the infected ulcer, about two inches wide, exposing the bone, wouldn’t heal. By the time April reached out to him, he says, it was draining so profusely he had to change his bandages six times a day.

When his newfound family told him about their miracle tree, he made plans to reunite with them in Concepcion. He arrived July 2018. He placed his foot against the bark of the tree. On the drive back to Illinois, the wound stopped draining. When he arrived for his next doctor’s appointment, the wound on his foot had partially closed. When the hole was the size of a dime, he says, his doctor felt comfortable stitching it closed. Within a few months, all that was left was a small scar.

“It felt like my mom had planned this,” Cantu says. “It was like she knew before any of us that we could help him—that her tree could help him.”

Garcia did not live to see Cory’s wound heal—she died in 2017. Now the chair near the tree where she used to sit and pray is empty. But for fifteen years before her death, on holidays and on her birthday—even in the heat of the summer, when temperatures soared above 100 degrees—her family would gather by the tree to celebrate.

“I know it prolonged my mom’s life,” Gloria says of the tree. “She had a mission—a purpose that kept her active.”

In the last two years of her life, Garcia’s health slowly declined. For a decade or so in this area of South Texas, residents have been known to contract illnesses that some have attributed to by-products of oil drilling in and around Laredo and Alice. Among those illnesses are lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Garcia was eventually diagnosed with the latter.

At first, Garcia wasn’t bothered by her diagnosis; she would load her oxygen tank into her Jeep to run errands around town. Once she even visited Gloria in Nashville, and she kept up with her daughter as they toured the city. There were close calls, though. On more than one occasion, Garcia was taken to the local hospital’s intensive care unit, and doctors summoned her family so they could say their goodbyes. One time when she was hospitalized, her daughters made a crown of leaves from her tree to rest on her head. But every time she had a scare, Garcia would recover. “Once I woke up in her hospital room and she was sitting up in bed fixing her makeup,” Gloria says, laughing. “She always had one foot out the door, ready to leave.”

But her health continued to deteriorate. During the last weeks of her life, in the summer of 2017, Garcia was completely reliant on her oxygen tank. When she was hospitalized for a final time, she reassured her daughters that she wasn’t scared. “She told us not to cry for her,” Cantu says. “She told us from the beginning that she would always come back to us.” Garcia’s funeral was held on August 7, 2017, at the church she grew up attending.

The tree near Concepcion is not the first to inspire pilgrimages nor to become the subject of sensational stories, and a rich, cynical body of research has grown around such sites. In 2014, researchers from the University of Toronto found that pareidolia, the phenomenon of finding faces and patterns in inanimate objects, is not unusual. “It’s common for people to see nonexistent features because human brains are uniquely wired to recognize faces,” lead researcher Kang Lee said in an interview. The effect is magnified when people expect to encounter something, which could explain why the Virgin Mary might appear to someone. Visitors might just see what they want to see in the bark. And perhaps the well-proved “placebo effect” is responsible for the relief of pilgrims’ physical pains.

But to Garcia, the tree was exactly what she’d always hoped it would be.

Inside the chapel, Cantu and Gloria show me a video of their mother. It’s a home movie from 2005, when nearly 1,800 visitors came to the tree in one day. (A minister from Corpus Christi had organized a large group trip.) Gloria smiles as she reminisces to me about her mother: her attentiveness, her smile, and the rosary she wore around her neck. Cantu stands next to the TV, pointing out different attendees and recalling the energy in the air that day.

In the video, Garcia buzzes about, chatting with visitors who have driven from across the country to pray at the tree. She’s beaming. This—hundreds of people united in faith, looking for hope—is exactly what she prayed for.

This article originally appeared in the February 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Under the Miracle Tree.” Subscribe today.