Regino Rojas is choking back tears. “It feels like I’m starting all over again, with the same fears, the same anxieties,” says the usually jovial, carefree owner of Revolver Taco Lounge in Dallas’s Deep Ellum entertainment district. He sounds nearly defeated but determined. Since March 16, when local officials closed restaurant dining rooms and bars to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, Rojas has had to furlough his employees and shift his business model toward takeout only for now. “I told them this is not a firing situation, but I have to obey the government’s order.” Rojas expects to welcome back former employees once the pandemic passes.

Rojas’s restaurant relies on foot traffic. Customers can still call ahead or walk up for window service, but there are fewer of them. “I’ll keep going. I have a family behind me that supports me, and that’s all I need.” He adds that prior to the pandemic, he always hated his restaurant’s little sliding window. He now depends on it. “I never I thought I was going to use it. It’s just there. But it’s saving my life right now.”

Like Revolver Taco Lounge, most taquerias and Mexican restaurants are family-owned operations run on small margins with minimal staff. Over the past few weeks, I’ve listened to the stories told by taqueros, food business owners, cooks, and others in the restaurant industry. Some owners, like Rojas, have furloughed employees or pivoted to a takeout and/or a delivery model to continue to pay the bills. Those are the lucky ones. The stories I’ve heard from others, including restaurant managers, chefs, cooks, bartenders, and spouses of workers, involve children who need feeding and abuelas who refuse to stop cooking despite a risk of exposure to the disease that has wreaked havoc on the hospitality-service industry and small businesses.

Before the COVID-19 crisis is over, America’s nearly $1 trillion restaurant industry will lose an estimated $225 billion, and it will lose five to seven million jobs over the next three months alone, according to the National Restaurant Association’s plea to Congress. The median small restaurant—any restaurant—has only sixteen days’ worth of cash reserve. That includes the more than 50,000 restaurants and their 1.5 million employees in Texas.

Despite all of this depressing news, the taco offers hope. As Andrew Savoie, chef and co-owner of Resident Taqueria, told me over the phone, “There has never been a better time to sell tacos. They’re quick, versatile, healthy, and portable.” He’s right. Rojas echoes Savoie’s remark. “I’m very blessed to have a product that I can prepare and serve right away.”

Tacos have survived much worse than the current pandemic.

First, Spanish colonizers and later the Mexican elite denigrated corn (the taco’s original foundation) as the food of a barbaric culture and glorified wheat as the food of the civilized. The attempt to eradicate corn in favor of flour didn’t work. Rather, wheat flour was integrated into the Mexican diet, including as an element of some tacos. Whatever was thrown at the taco, the taco took on as its own. For example, the taco al pastor developed from Middle Eastern shawarma, which Lebanese immigrants brought to Mexico in the early twentieth century. More recently, Korean tacos, Indo-Mex tacos, and pricey modern chef-driven tacos (sparked by a renewed interest in ancient artisan techniques) developed north of the border. With each passing year, tacos become more popular. They’re the inspiration for fashion as well as the subject of documentaries, a legion of books (including my own), a battle over an emoji, and memes. So many memes.

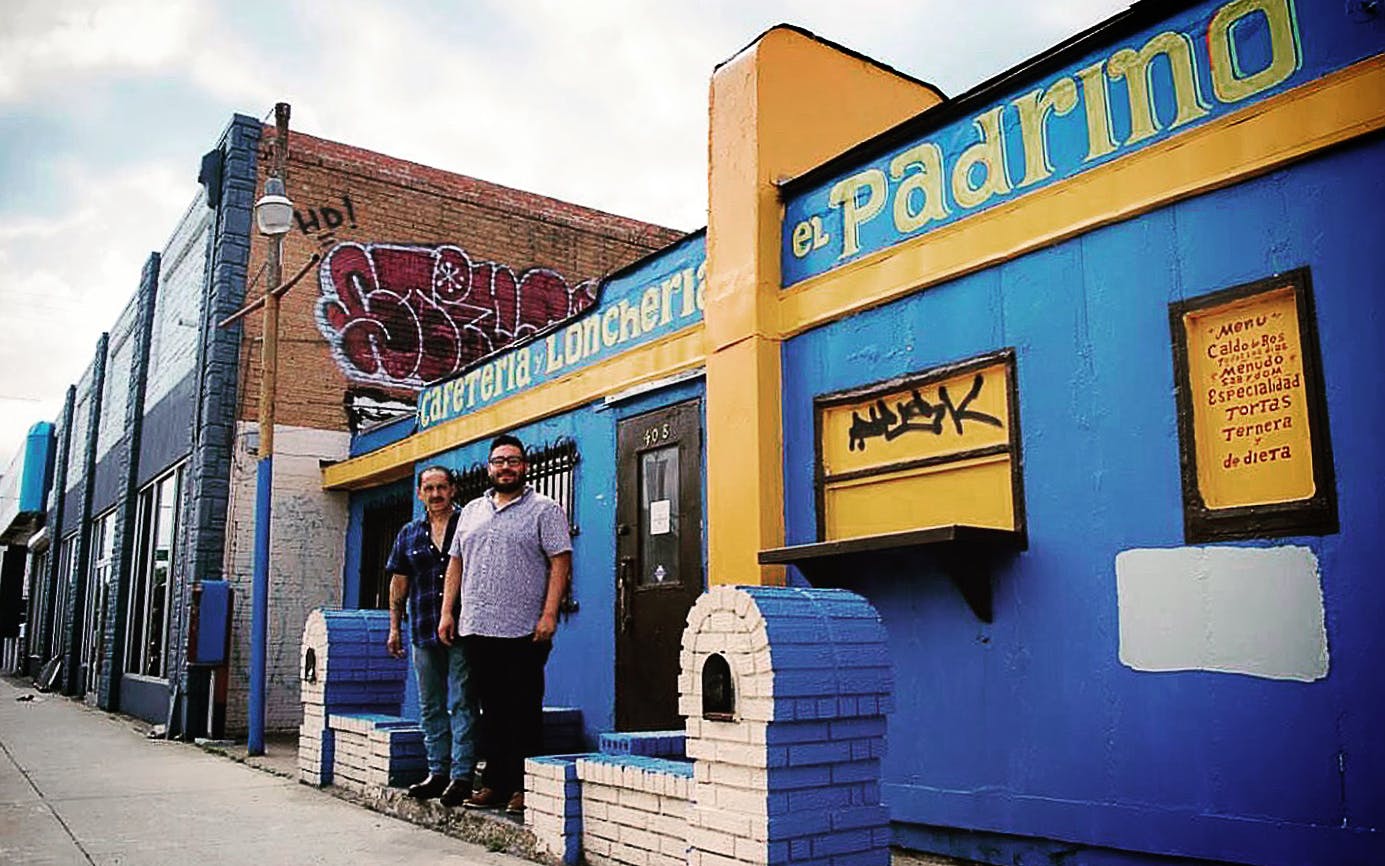

Then came COVID-19. Mexican restaurants and taquerias are shuttering at a rapid pace, one I’ve tried to keep up with and share information about here and in my TacosNotCOVID19 Instagram story highlights. The toll has been unrelenting, especially for the wave of unemployed workers, many of whom are undocumented and cannot benefit from a system they pay into. But the restaurant business is adapting as best it can, and quickly. While many of us are sheltering at home, we can continue to support local businesses, especially mom-and-pop shops like El Padrino in Dallas, Ray’s Drive Inn in San Antonio, and Wall St. Cocina in Midland via delivery, drive-through, or pickup. There are hundreds you can help: just check out the aforementioned Texas Monthly list, which is updated regularly.

Trucks and pop-ups are especially resilient. They can adapt faster and operate at the thinnest of margins. They’re also the most like the traditional puesto (taco stand) of Mexico. Tarrant County-based pop-up Bad Spanish Tacos has taken to delivery. In Austin, at Vaquero Taquero, which began as a breakfast taco pushcart before eventually becoming a small storefront, brothers Miguel and Dani Cobos will jump in their little black pickup truck to bring you tacos al pastor in fragrant, handmade corn tortillas. San Antonio-based food truck El Remedio is taking preorder is taking phone preorders for weekend pickup. Also in San Antonio, Comadre Panaderia owner Mariela Camacho prepares and sells creative Mexican pastries, such as a strawberry-hibiscus concha and a soft and tangy guava and cream cheese empanada, as well as fresh Sonoran flour tortillas; she also is willing to drive to customers—even in Austin.

For Camacho, adaptability is essential to survival. “My initial response to continuing to try and make food was honestly just from being scared [of] not having money,” she tells me over the phone. “I think that is so ingrained in us. I grew up really poor. My parents are immigrants and we always struggled with money. I’ve got to hustle even harder now. By being there, I just want people to know that I’m around to be able to deliver. I think it’s also still important for people to know that there are other people struggling.”

Luis Robledo, owner of Cuantos Tacos, a squat yellow truck parked on Manor Road in Austin, closed his business temporarily March 17 but reopened a week later. His Mexico City-style taco operation was once again selling subtly flavored lengua, silky suadero, and rich chorizo served from the same chorizera, the stainless steel concave pan with a raised center that acts as secondary cooking surface. “Everything was changing by the hour,” he tells me. “I decided to take a risk and just close down the whole week and see how things were going to be playing out—they’re still playing out.” He decided to reopen because he has a family to support, and he has a small team he wants to keep employed. Besides, it’s not like there’s a rush on beef tongue, he jokes. He has access to the product and intends to sell to-go for as long as he needs to. The fact that Robledo’s truck is on an open lot with a lot of space for customers to spread out, eat in their cars, and wait for their orders helps. Nevertheless, he admits it feels like he’s starting over again too. “It’s like I’m back at day one.”

It’s true that not all the businesses currently offering food will be able to remain open the longer this crisis continues. Not all the restaurants that closed or will close will be in a position to reopen after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides. However, I believe the small family-owned taquerias, Mexican restaurants, pop-ups, and taco trucks with the flexibility to ride through this uncertain time are the ones best suited to survive. That flexibility depends on the taco, which will endure, especially in Texas. I put my trust in the taco. You should too. But doing that requires supporting those businesses by ordering delivery or pickup. As Rojas tells me, “Tacos will feed America.”

- More About:

- Tacos

- San Antonio

- Midland

- Dallas

- Austin