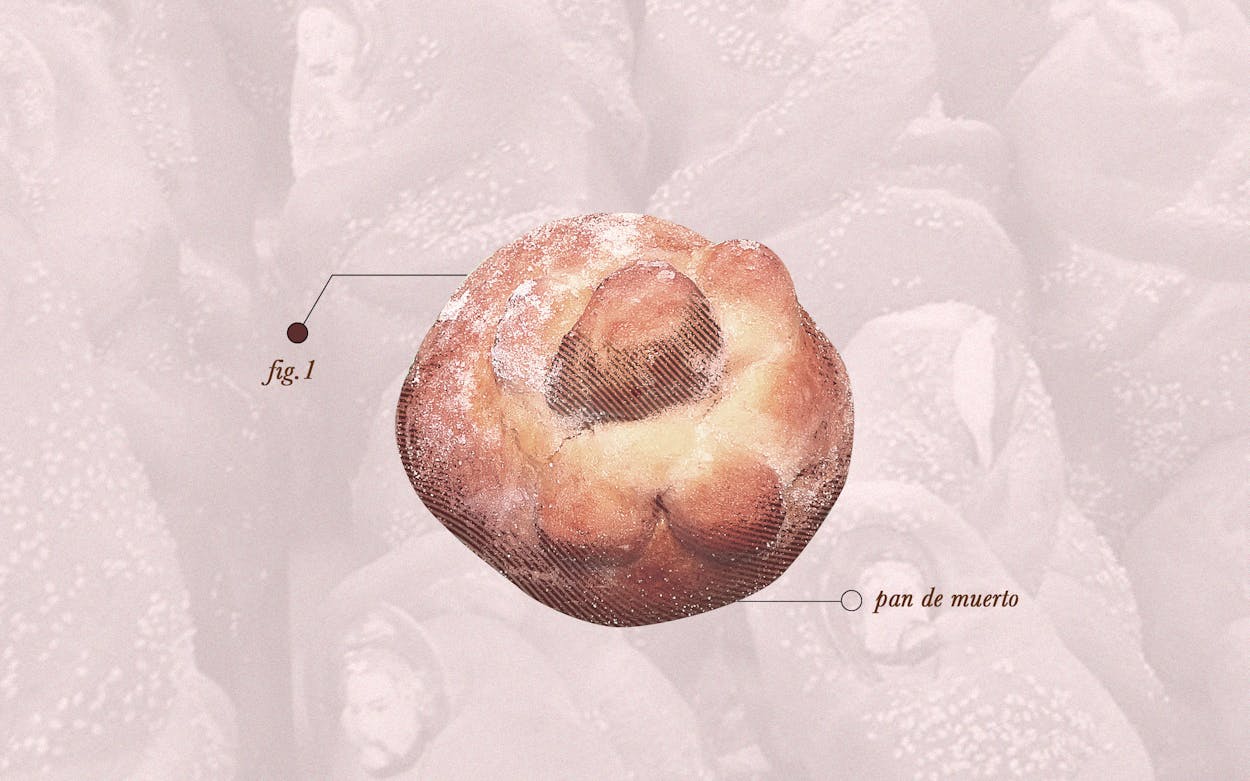

At Mexican bakeries across Texas, shelves are stocked this month with round, sugar-dusted loaves of pan de muerto. Panaderías sell this “bread of the dead”—typically decorated with dough in the shape of bones or skulls—from September through Día de los Muertos. Over two days and nights (November 1 and November 2), the joyful, colorful holiday honors ancestors and loved ones who have died.

Pan de muerto is an essential part of a Día de los Muertos home altar or shrine, also called an ofrenda. The bread adorns the altar openly or in a basket, and is meant to nourish the dead when they return to the land of the living during Día de los Muertos. The loaves share crowded space with photos of departed loved ones, a few of their favorite beverages or snacks, and garlands of bright marigolds. Ofrendas also commonly include calavera sugar skulls and a rosary, cross, or crucifix.

It has a complex sweetness that comes not just from sugar, but also from anise and orange blossom essence. Manuel Tellez, co-owner of Maroches Bakery in Dallas’s Oak Cliff neighborhood, uses the latter in his pan de muerto. The result is a spongy, challah-like loaf rife with buttery and citrus notes, after which rides a light licorice finish. Sugar falls everywhere as you eat. Tellez’s pan de muerto is so popular that he offers it year-round. A Guanajuato native, he emphasizes how widely the bread varies across Mexico. “We had different kinds of pan de muerto: the one you eat in Oaxaca, the one you eat in Veracruz, the one you eat in central Mexico, the one from Mexico City, and the one in the north of Mexico,” he says. Sometimes it’s studded with sesame seeds and pepitas (pumpkin seeds), then decorated with illustrations painted on in colorful dyes and sugars. Amaranth flour is among the grains that might be used instead of or in addition to wheat flour; Tellez also mixes pumpkin flour and orange flour into his dough.

The choice of flour is significant. Although Día de los Muertos has pre-Hispanic roots, the bread itself is usually made from wheat flour, brought to Mexico by the Spanish. The ingredient ties it to conquest and conversion. “Wheat is connected directly with the Catholic Church and how the religion was imposed and taught to the indigenous people,” explains Iliana de la Vega, executive chef and co-owner at El Naranjo in Austin. She points out that even as Día de los Muertos gains popularity throughout Mexico and the United States, especially in California and Texas, the holiday’s connection to Indigenous communities in Mexico remains strong. In a market in Oaxaca, her mother’s native state, de la Vega has seen pan de muerto in the shape of the human body, complete with a painted face.

Although my wife’s family hails from Mexico and has Indigenous roots, we don’t build an altar every year. Sometimes life gets away from us. When we do set up a shrine, we certainly don’t place pan de muerto on it, lest one of our dogs mistake it for a treat. I feel some shame in that. As a child, de la Vega also felt shame around the holiday, though of a different type. When she was growing up in Mexico City, Día de los Muertos was not widely observed there. But following Oaxacan traditions, her mother took the celebration seriously, much to her daughter’s embarrassment. “[She] used to make the altar every year, so when friends from school came to visit, they always asked if my mom was some sort of witch,” de la Vega says. “I remember asking my mom to stop building the shrine, which she obviously refused. So I stopped inviting friends over during those days. With time, I realized the meaning of it. I am very grateful that my mom maintained her values.”

Mariela Camacho, of San Antonio bakery pop-up and delivery service Comadre Panadería, connects pan de muerto to colonization and adaptation. The loaves are sometimes topped with red sugar, which Camacho theorizes may be symbolic of the human sacrifice practiced by some Indigenous cultures before the Spaniards arrived: “I believe it signifies blood or the heart.”

Ancient, colonial, and contemporary traditions are woven together in Día de los Muertos—and in the taste of its signature bread. After all, the holiday coincides with All Saints’s Day and All Souls’s Day. “[Pan de muerto] represents the end of a culture and the beginning of another one, like the end of a human sacrifice is the beginning of Christianity,” Tellez says. “It’s our way of saying, ‘Okay, we accept the religion but not the way you want it.’”

More important, though, is the personal connection. “Coming from a family from Oaxaca, where Día de los Muertos is very important, we have always made an altar and either bake or buy the pan de muerto,” de la Vega says. “It is a very profound way to celebrate and honor your loved ones who have departed.”

- More About:

- Tex-Mexplainer

- Tacos

- San Antonio

- Dallas

- Austin