One morning in late January 2019, Rhogena Nicholas texted a prayer to her mother, Jo Ann Nicholas, just as she did every day. A widow in her eighties, Jo Ann could no longer make the four-hour drive from Natchitoches, Louisiana, to visit her daughter and her son-in-law, Dennis Tuttle, at their bungalow in the Pecan Park neighborhood of southeast Houston, but the family remained close, texting and speaking on the phone regularly. Rhogena, 58, worked as a bookkeeper, among other jobs. That afternoon, on January 28, she called Jo Ann to warn her against venturing outside in the icy weather gripping central Louisiana. Then she said goodbye, telling her mother that she and Tuttle were going to take a nap.

Less than an hour later, eleven armed Houston Police Department officers broke down the door of 7815 Harding Street and killed Rhogena, Tuttle, and their dog in a fusillade of bullets; autopsies would reveal that police shot Rhogena three times and Tuttle nine times. Four officers were also shot, allegedly by Tuttle, a 59-year-old disabled Navy veteran.

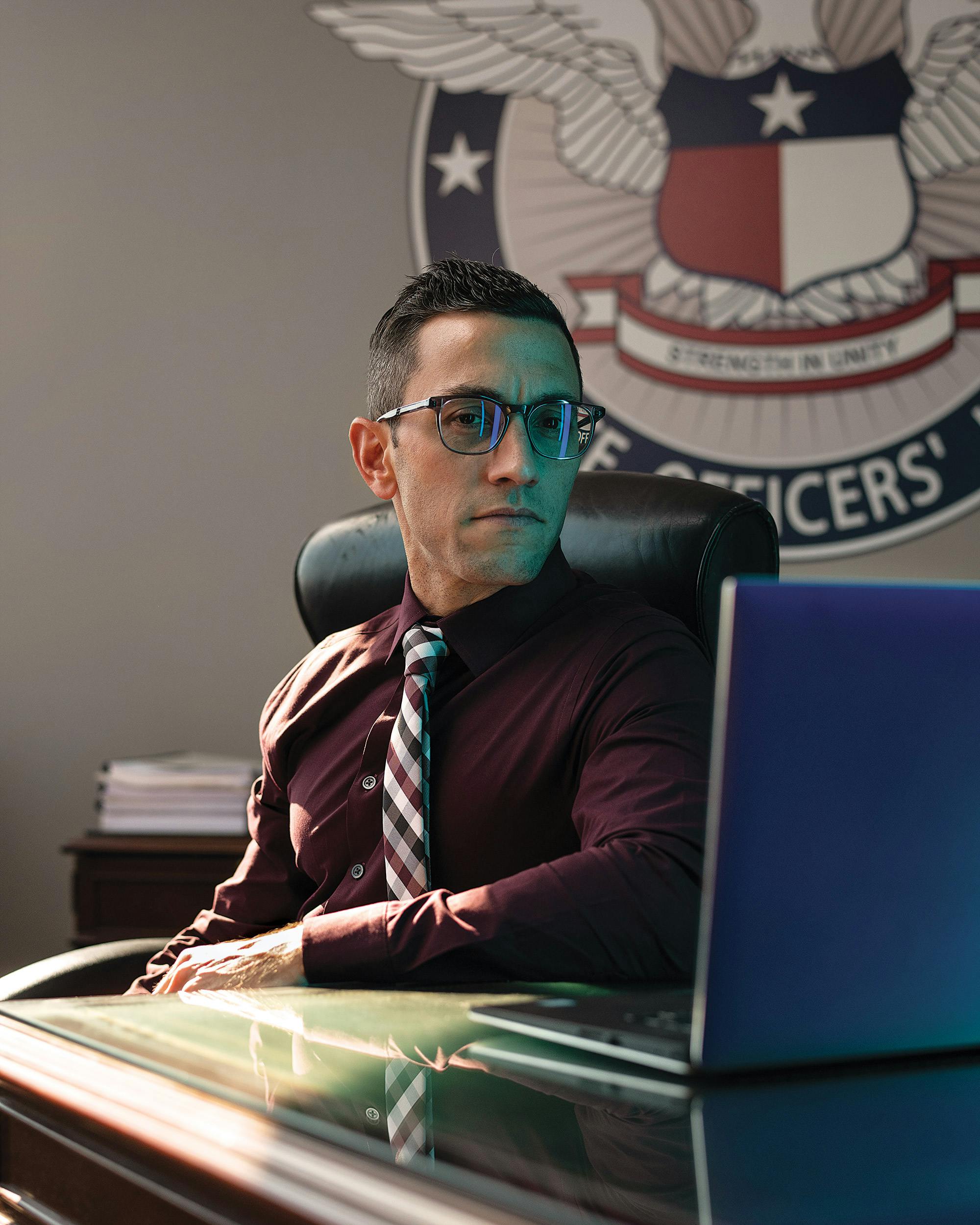

At a press conference that evening, Houston police chief Art Acevedo said that a neighbor had tipped off officers that heroin was being sold at the Harding Street home, leading a judge to issue a search warrant. Then Joe Gamaldi, the 37-year-old president of the Houston Police Officers’ Union, stepped up to the microphones.

A native of Long Island who started his career in the New York Police Department, Gamaldi has a slender build and short stature—his former NYPD partner affectionately calls him a “good little man”—that belie his street fighter instincts. And on this night, with four of his officers in the hospital, he was ready for a brawl.

“We are sick and tired of having dirtbags trying to take our lives,” Gamaldi announced in his reedy New York accent, jabbing his forefinger at the assembled reporters. “And if you’re the ones that are out there spreading the rhetoric that police officers are the enemy—well, just know, we’ve all got your number now.” To Gamaldi, the deadly Harding Street raid was the latest skirmish in what he considers a war on cops being waged by a panoply of sinister left-wing groups.

But Nicholas and Tuttle weren’t heroin dealers. There was no heroin; the warrant was based on false information, and the narcotics officer who led the Harding Street raid has since been charged with two counts of murder. The couple’s families believe, based on an independent evaluation of the crime scene by a forensic investigator that they commissioned, that the injured officers were hit by friendly fire. Those relatives have filed a petition asking the City of Houston to turn over ballistics evidence from the raid.

In the aftermath of that Monday’s events, the prayer Nicholas texted her mother in the morning seems especially bittersweet. It began, “Dear Lord, thank you for a new day and week ahead that is full of promise and possibilities.”

I first met Joe Gamaldi this past July, at a tony juice bar in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood. COVID-19 cases were approaching a summer peak in Texas, and we were the only customers there. Gamaldi wore a floral-patterned dress shirt tucked into neatly pressed rose-colored khakis that ended at his ankles, revealing a pair of monk-strap loafers. His close-cropped black hair and tortoiseshell glasses made him appear more like the CEO of a tech start-up than a cop; before we met, he told me to look for “the nerdy-looking guy with glasses.”

After we’d taken off our masks to drink iced coffees, I asked Gamaldi if he regretted his inflammatory statement about the Harding Street raid.

“In that moment, we had four police officers shot, one of which will never walk again,” he said. “Obviously, after the fact, [we learned] that the warrant was falsified. But the other people on that team didn’t know that. The officer who is paralyzed, he didn’t know that at the time. I probably should have been more careful with my words and really drilled down on what I was trying to say. But, you know, I’m an emotional guy. And in that moment I was upset and angry, and I spoke from the heart.”

What about linking Nicholas and Tuttle, who had no known connection to any activist groups, to law enforcement critics? Gamaldi responded that the “constant drumbeat of anti-police rhetoric” created an atmosphere in which those “who may already be on the edge” decide to shoot at police officers. “If all you hear from people in the media and politicians is that we’re out there murdering people, that we’re the worst people in the world, then people who are already at that point may take that additional step.”

Gamaldi’s full-throated support of the police, and his equally full-throated denunciation of groups he believes are anti-police, has recently thrust him into the national spotlight. In August 2019, eight months after the Harding Street raid, he was elected national vice president of the Fraternal Order of Police, the country’s largest police union, which endorsed President Trump in 2016 and 2020. He has visited the Trump White House twice and is a regular guest on Fox News and other conservative media outlets.

But since being sworn in as HPOU president in January 2018, Gamaldi has made at least as many enemies as friends. Annise Parker, Houston’s mayor from 2010 to 2016, described him as a “bomb-thrower.” “I don’t know whether that helps him with the rank and file, but it certainly doesn’t help him with the mayor or city council,” she told me. “And I don’t know that it helps him with the majority of the public.”

Harris County commissioner Adrian Garcia, formerly a sheriff, a Houston City Council member, and a 23-year veteran of the Houston Police Department, expressed similar unease about Gamaldi’s Manichaean rhetoric. “It’s important that a union leader exercise the same tactics that you would ask a patrolman to exercise out on the streets,” Garcia said. “If you come across domestic violence, you don’t say and do things to incite the situation. You come in as a calming force.”

The ultimate test of a union leader’s effectiveness is how he or she handles contract negotiations. In 2018 Gamaldi led the talks for the HPOU’s current two-year contract, which was quickly and unanimously passed by the Houston City Council, even though the deal included provisions that critics say make it almost impossible to hold police officers accountable for misconduct. That contract expires in December. But the road to a new one has become significantly bumpier, thanks to emboldened local activists pushing for fundamental reforms.

In June, more than a hundred Houstonians called into an eight-hour virtual city council committee meeting on the topic of police reform, many of them demanding that the council defund or abolish the police department. In September, a task force convened by Sylvester Turner, Houston’s mayor, released a report on police reform that included a long list of recommendations. “The public is always ahead of the politicians,” said Ron DeLord, a union lawyer who led the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas for thirty years. “Otherwise, women wouldn’t have gotten the vote. American Indians wouldn’t have gotten citizenship. Gay rights, gay marriage, marijuana . . . the public attitude starts changing, it builds up steam, and there’s a tipping point. And that tipping point [for police] was George Floyd.”

There are several obstacles to police reform: training that teaches officers to constantly fear for their lives, district attorneys reluctant to indict the cops they work with every day, “qualified immunity” protection that makes it almost impossible to successfully sue officers. But perhaps the greatest barrier, and the one likely least understood by the general public, is the political power of police unions, which represent a majority of the country’s approximately 800,000 law enforcement officers.

The detailed contracts that each union negotiates with its local city or county govern almost every aspect of a police officer’s job, from clothing allowances and fitness requirements to salaries and benefits. They also generally lay out a disciplinary appeal process that gives officers the opportunity to challenge, and in many cases overturn, sanctions for misconduct.

POLICE REFER TO THEMSELVES AS THE “THIN BLUE LINE” PROTECTING SOCIETY FROM ANARCHY. BUT THERE’S ANOTHER BLUE LINE—THE ONE PROTECTING POLICE FROM ACCOUNTABILITY.

Written in opaque legalese, union contracts are, at least in the short term, impervious to protest marches, unmoved by public opinion, and indifferent to presidential elections. Contracts live in the realm of the law, not the hothouse atmosphere of social media. Often negotiated behind closed doors and ratified by city council members elected with the help of campaign contributions and volunteer work by union members, contracts protect cops from activists, politicians, and even police chiefs, who, as political appointees, often find themselves in conflict with unions. Perhaps most significantly, as the nation has discovered in recent years, these contracts often protect police who use excessive force from the consequences of their actions.

Police refer to themselves as the “thin blue line” protecting society from anarchy. But there’s another blue line—the one protecting police from accountability. In Houston, that line is being held by Joe Gamaldi.

Gamaldi grew up in a middle-class suburban neighborhood on Long Island, where the value of unions was impressed upon him by his grandfather, an Italian immigrant and brickmason whose union salary eventually allowed him to purchase two homes, in New York and Florida. After earning a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from the University of Hartford, Gamaldi joined the NYPD in 2005, at the age of 22.

Like nearly all new NYPD officers at the time, Gamaldi was assigned to foot patrol straight out of the police academy—in his case, in East New York, a neighborhood in Brooklyn that has long had one of the highest crime rates in the city. When Gamaldi showed up at his precinct on his first day, his supervisor handed him a map and pointed out the two blocks he was responsible for. “I walked, I think, three miles out to my post,” Gamaldi recalled. “People were just like, ‘Welcome to the neighborhood, rookie!’ They’re throwing things off the buildings at you—batteries, eggs, all types of stuff. It was definitely a trial by fire.”

After six months of foot patrol, Gamaldi stayed in East New York and was assigned his first partner, Dave Siciliano, a three-year veteran whom Gamaldi credits with teaching him how to be a cop. They spent their time driving the streets in a patrol car, responding to one call after another: assaults, shootings, robberies in progress, stolen vehicles. “I can’t imagine anywhere tougher to patrol straight out of the gate,” Siciliano told me. “It’s hard going from suburban life to the heart of inner-city violence. It’s difficult to describe that shell shock.”

The NYPD’s relationship with the East New York community was tense. “The more police interactions you have, the less community trust you’re going to have. And when you have violence, you’re going to have police interactions, whether warranted or unwarranted,” Siciliano said. On September 2, 2007, Siciliano and Gamaldi responded to a call about a man named Audi Wilson, who had allegedly pointed a gun at a fellow spectator during a soccer match. Arriving on the scene as the crowd was exiting the stadium, the officers met the caller, who pointed them to Wilson.

According to Gamaldi, Wilson pulled a gun and stuck it into Siciliano’s stomach. “I tackle him, and we’re on the ground,” Gamaldi said. “Everybody’s screaming at us because we’ve tackled the man in the middle of all of this. We get him into custody, we recover the gun, and we have to get him out of the crowd as quickly as possible, because obviously the crowd’s turning on us.” (Neither Wilson nor his lawyer could be reached for this story.)

Wilson alleged in a 2010 lawsuit that the two officers “brutally attacked” him from behind without probable cause and called him the N-word. After Wilson’s lawyer repeatedly failed to show up in court, the lawsuit was withdrawn. Wilson also filed complaints against Gamaldi and Siciliano with New York’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, alleging “force” and “abuse of authority.”

The CCRB ruled one of Wilson’s complaints “unsubstantiated,” which, according to the board’s website, means “the available evidence is insufficient to determine whether the officer did or did not commit misconduct.” Another complaint was declared “exonerated,” meaning the “officer was found to have committed the act alleged, but the officer’s actions were determined to be lawful.” The NYPD later gave Gamaldi an award for his actions that day.

Being sued by Wilson left Gamaldi with a jaundiced view of civilian complaints. “He was saying that we did all these horrible things, that we said all these horrible things,” Gamaldi told me, his incredulity undimmed by the decade that has passed since the lawsuit. “I’m like, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ ” He and his partner did “absolutely nothing wrong,” and they definitely did not use the N-word, Gamaldi maintained. His conclusion: “People put things in complaints like that because they’re trying to get money out of them.” The incident also gave him a deeper appreciation for police unions; Gamaldi and Siciliano were defended against the CCRB complaints by the New York City Police Benevolent Association and against Wilson’s civil suit by New York City’s legal department. Partly out of frustration with Wilson’s CCRB complaint, Gamaldi transferred to the Houston Police Department in 2008, when he was 24. He was also tired, he said, of living in a three-bedroom apartment just outside Queens that he shared with two firefighters. A visit to his brother, a United Airlines executive who was based in Houston at the time, sealed the deal. “I was like, ‘You’re kidding: You can have a home for $150,000 or $200,000? I’m in.’ ”

At the HPD academy, Gamaldi met his future wife, Alexa, a fellow officer with whom he now has two daughters. He bought a house in the suburbs. And he met Ray Hunt, then the vice president of the Houston Police Officers’ Union, who would become a mentor and father figure to Gamaldi.

OVER THE SUMMER, AS THE TEMPERATURE OF GAMALDI’S RHETORIC ROSE, SO DID HIS VISIBILITY.

The two first crossed paths when Hunt gave a presentation to the police academy. When the cadets were encouraged to contribute $5 a month to the HPOU’s political action committee, which supports union-friendly candidates, Gamaldi raised his hand and asked if he could donate more. “I was like, ‘Dude, what’s your name?’ ” Hunt recalled. A few years later, when a position opened up on the HPOU board, Hunt immediately thought of the eager young officer from his presentation. Gamaldi was then patrolling Acres Homes, a predominantly Black neighborhood in northwest Houston. “He was exactly what we needed,” Hunt told me, “a young officer who got what we do here at HPOU.”

Gamaldi’s fellow cadets had long joked that he was destined to be a union leader, given his preoccupation with officers’ rights. “If they wanted us to stay late, I’d be like, ‘Hey, we’ve got to get overtime for that,’ ” he said. After spending two years on the HPOU board, Gamaldi was elected second vice president in 2013, the same year Hunt became president. When Hunt announced in 2017 that he wouldn’t run again, Gamaldi, just 34, was elected to the presidency with 91 percent of the vote.

As president he moved quickly to overhaul the union’s public relations operation, to better “jump in front of negative news stories.” In 2018 Jose Gomez, the 41-year-old owner of a local moving company, sued three HPD officers for assaulting him during a traffic stop. Gamaldi responded by going on local news to claim that Gomez had been resisting arrest and that the officers had acted appropriately. “In the past, these cases would be handled with an answer of ‘we can’t comment because litigation is ongoing,’ ” Gamaldi explained in the June 2018 issue of Badge and Gun, the HPOU’s monthly newsletter, “but I believe in defending officers and not allowing them to get dragged through the mud.” (The criminal charge against Gomez for resisting arrest was eventually dropped; his lawsuit is awaiting trial.)

Gamaldi had already taken charge of the union’s social media accounts, which regularly lob salvos against criminal suspects, whom he has described as “dirtbags,” “miscreants,” and “cowards.” In 2018 he campaigned vigorously against Proposition B, a Houston ballot referendum guaranteeing equal pay for police officers and firefighters of the same rank. According to Mayor Turner, the measure would have blown a hole in the city’s budget and forced it to lay off workers, including police officers. When Prop B passed with nearly 60 percent of the vote, the HPOU joined the City of Houston in successfully suing to overturn it for violating state law on collective bargaining.

“An overwhelming number of voters in the city of Houston voted for the proposition,” said Patrick “Marty” Lancton, the president of the Houston Professional Fire Fighters Association, who noted that firefighters have had only a single 1 percent pay raise since 2013. “For HPOU and the mayor to be operating in tandem after putting millions of dollars into a campaign that they lost was just flabbergasting to our firefighters and their families.”

Three days after George Floyd was killed by police officer Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, sparking nationwide protests, Gamaldi issued a statement to union members via Twitter. Without mentioning Floyd by name, he advised officers to avoid a similar incident: “If a fellow officer on your scene is doing something that you believe is wrong, from what you see and feel, you have an obligation and duty to STEP UP and SPEAK UP.”

But as millions of Americans continued demonstrating for racial justice across the country, including at a massive march in Houston on June 2, the tone of Gamaldi’s social media posts veered into the apocalyptic, decrying “extreme violence against officers” after two cops were shot in New York City one night in June. This turn, from initially condemning incidents of police brutality to lambasting protesters, is a characteristic move for the union boss: call it the Gamaldi pivot.

It’s an effective strategy. Over the summer, as the temperature of Gamaldi’s rhetoric rose, so did his visibility. He appeared on The Glenn Beck Program, Newsmax, and Fox News to criticize cities such as Minneapolis and Austin for pledging to dismantle, partially defund, or reorganize their police departments. When violence flared in Portland and Seattle later in the summer, Gamaldi went on Fox & Friends to assail the cities for not cracking down harder on the police critics.

“The governments in Portland and Seattle are, frankly, implicit in this right now,” he said, his voice rising in indignation. “They’ve allowed antifa terrorists—and that’s what they are. They’re terrorists, okay? They’re using violence and fear to influence how people view things—to run wild, all while tying the hands of our police officers.”

On criminal justice matters, Gamaldi and the White House are in lockstep; he regularly praises Trump on social media. On July 15 he met with Vice President Mike Pence at the White House to discuss the ongoing protests and the state of law enforcement. Gamaldi’s unwavering support for Trump has earned him the nickname “Mini-MAGA” from Black Lives Matter Houston cofounder Ashton Woods. “He’s the vice president of the Fraternal Order of Police,” Woods told me. “You know what that looks like, and you know who they support.”

Gamaldi believes he has little choice but to line up behind Trump, given what he perceives as a lack of appreciation for police from Democratic politicians. “Law enforcement officers are desperate for people to support them, because we feel like we’re being attacked by everyone,” he said. “And here you have the most important person in the world saying that he supports law enforcement.”

But Trump has a long history of encouraging the kind of police brutality that Gamaldi says he opposes. During a 2016 rally, the then presidential candidate lamented that security guards weren’t able to use sufficient violence against protesters. In 2017 he appeared to instruct an audience of Long Island police officers to be harsher with suspects: “When you see these thugs being thrown into the back of a paddy wagon—you just see them thrown in, rough—I said, ‘Please don’t be too nice,’” Trump told the laughing cops.

“I BELIEVE OUR SYSTEM IS FAIR. IT’S FAIR TO THE CITY, IT’S FAIR TO THE DEPARTMENT, IT’S FAIR TO OUR OFFICERS.”

When I brought up the latter statement, Gamaldi grimaced. “When you say things like that, I’m sure it was probably off-the-cuff, but it’s not helpful,” he allowed. Several national law enforcement groups criticized Trump’s comments, but not the Fraternal Order of Police, which issued a statement suggesting that the president hadn’t intended for his words to be taken literally.

His support for Trump hasn’t prevented Gamaldi from aligning himself with Houston mayor Sylvester Turner, a Democrat. (The HPOU endorsed Turner in both his 2015 and 2019 campaigns.) Gamaldi told me that Turner was “a huge supporter of the police and probably the best mayor we’ve ever had in Houston.”

Their synergy has continued to pay dividends for the union. In June, while cities across the country were slashing police funding, Turner successfully pushed through an annual budget that included a $19 million increase for the HPD. Despite the vote’s taking place the day after George Floyd was buried in the Houston suburb of Pearland, the budget passed unanimously in the city council. An attempt by council member Letitia Plummer to redirect $11.7 million from the police failed to gain any support; Plummer ultimately voted for the budget anyway, explaining that “there were a lot of really good programs that the city was funding.”

Gamaldi works out of a spacious, utilitarian office on the third floor of HPOU headquarters, an inconspicuous commercial building near downtown Houston. Tacked to a bulletin board next to his desk is a quote from Theodore Roosevelt’s “Man in the Arena” speech: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better.”

In early September I met Gamaldi at his office to discuss contract negotiations, which had been repeatedly delayed by COVID-19 and the nationwide protests against police brutality. I asked how Houstonians could have confidence in a fair contract when the mayor and thirteen out of sixteen members of the city council have accepted donations from the HPOU’s political action committee. (In June, Austin’s mayor and every member of city council took a pledge not to accept union donations.) Gamaldi replied that the HPOU doesn’t get everything it wants.

“What didn’t the union get in the 2018 contract?” I asked.

“I mean, obviously, we wanted more money,” Gamaldi replied, leaning back in his chair and chuckling.

I pressed him: “What about the appeals process, the protections for officers accused of using excessive force? Are there things you want to strengthen?”

“No,” he answered. “I believe our system is fair. It’s fair to the city, it’s fair to the department, it’s fair to our officers. So there wasn’t anything that we were asking for in that last contract as far as discipline was concerned, like greater rights or anything like that.”

The HPOU’s current contract is 102 pages and contains a number of provisions seemingly designed to frustrate effective oversight. Officers accused of misconduct, for instance, are granted a 48-hour window before answering questions from an internal affairs investigator. During those two days, the accused officer must be given access to both the original complaint and written statements from witnesses, officers, and supervisors. Critics of the police contend that this arrangement gives officers, who have access to union-provided lawyers, a chance to get their story straight before answering questions under oath.

Under the contract, the Houston Police Department has just 180 days after an incident of serious misconduct to fire an officer; if the incident is discovered after that period, the department can impose a suspension of no more than 15 days. Similar provisions are common in big-city Texas police department contracts; last year, in San Antonio, an officer who was fired after giving a homeless man a sandwich filled with dog feces won his appeal because the punishment wasn’t handed down within 180 days.

Even if an offense is addressed within that period, Houston officers can appeal the internal disciplinary decision to either a civil service commission, composed of members appointed by the mayor, or, in the case of more serious punishments, an independent hearing examiner. The examiner for each appeal is chosen randomly from a pool of twelve professional arbitrators, half of them selected by the city and half by the union. Because the arbitrator can only sustain, reduce, or overturn the punishment, officers have nothing to lose by appealing— and much to gain. Between 2007 and 2012, the Texas Observer reported, arbitrators “reduced officer punishment in half of all cases and overturned it completely in about one out of six.” Arbitrators must be reappointed every two years, so they may have a vested interest in finding a compromise between the department and the officer.

Gamaldi and other union advocates argue that such protections provide due process to officers accused of misconduct, but, in practice, they ensure that officers are rarely disciplined. A Houston Chronicle investigation found that between 2008 and 2012, HPD’s internal affairs division reviewed 636 shootings by its officers and concluded that only one lacked justification: a case involving an officer whose unholstered gun accidentally fired as he was trying to arrest a suspect.

The political clout of police unions makes reforming their contracts extremely difficult—but not impossible. In 2017 the Austin City Council unanimously voted down the contract the local union had negotiated with Mayor Steve Adler, sending both parties back to the bargaining table. The vote followed a determined eighteen-month campaign led by the Austin Justice Coalition and inspired by the police killing of a teenager named David Joseph and by the brutal arrest of 26-year-old Austin schoolteacher Breaion King during a 2015 traffic stop. Austin Police Department officer Bryan Richter had dragged King out of her vehicle and slammed her facedown onto the asphalt, yet he received only a reprimand for the incident. When video of the arrest leaked to the press a year later, Art Acevedo, at the time the Austin police chief, publicly apologized to King but couldn’t impose additional punishment on Richter because of the union contract’s 180-day rule.

“We knew that for that reason alone, we needed to go and try to work on that in the contract itself,” recalled Sukyi McMahon, the strategy director of the AJC board. Unlike in Houston, contract negotiations in Austin are open to the public, and when weekly talks began in May 2017 between the city and the union, the AJC made sure they had representatives in the room. “We couldn’t talk, but we could take notes and then disseminate the information back to the community to let them know this is awful, this is bullshit,” Chas Moore, the founder and executive director of the AJC, told me.

When the final contract ended up including just one of the many reforms the AJC had sought—an online civilian complaint system—the group launched a public information campaign to discredit the contract, hosting community forums in the districts of every council member. “We built this super-huge coalition, a little bit of everybody,” Moore said. “We had the environmentalists, we had the health-care folks, people who love dogs, people who love babies, people who love bikes.”

Ignoring the union’s warning that hundreds of officers would retire if they rejected the contract, the Austin City Council did exactly that, late on the night of December 13, 2017. (Only 33 officers retired from the force of more than 2,600.) With the police union refusing to renegotiate, the old contract expired at the end of the year, and Austin reverted to Chapter 143 of the Texas Local Government code, which regulates big-city police and fire departments without contracts. The union eventually returned to the table in the summer of 2018 with a new chief negotiator who sought out the AJC’s input.

The final contract relaxed the 180-day rule, prevented short suspensions from being automatically downgraded to written reprimands, and expanded the responsibilities of the Office of Police Oversight, which can now independently review citizen complaints, audit footage from dashboard and body-worn cameras, and recommend discipline to the Austin police chief—then publish the results of the investigations online. Although it didn’t include all the changes the activists had requested, the contract was a major step forward for them. And despite including a 9 percent pay raise spread over four years, the total cost of the salaries and benefits in the contract was $44 million, far less than the original proposal.

With the current Houston police contract expiring at the end of 2020, local activists are trying to replicate the success of their Austin counterparts. In Houston, however, the talks between the city and the union have always taken place behind closed doors. In July, the ACLU of Texas called on Mayor Turner to open these meetings, arguing that “policing is a public service subject to democratic governance.” The three Houston City Council members I spoke to, including Greg Travis, a conservative who represents a wealthy section of west Houston, told me they want to be more involved in negotiations.

Travis, who was on the city council when the current contract was approved, in 2018, expressed frustration at being shut out of the talks. “No council member had any input on the contract,” he said. “They come to us for approval; they don’t come to us for discussion.” In July, city director of communications Mary Benton told the Houston Chronicle that “contract negotiations will move forward at Mayor Turner’s direction and in the city’s best interest.” (Turner declined an interview request for this story.)

Thanks to the HPOU contract’s “evergreen clause,” if a new contract isn’t ratified by the end of 2020, the current contract will be extended indefinitely, with officers receiving an automatic 2 percent pay raise on July 1, 2021. But that doesn’t mean the union lacks an incentive to negotiate or that activists don’t have leverage to demand reforms. “At some point we have to have an agreement in place long-term,” Gamaldi acknowledged. “Otherwise, our officers will never get another raise for the rest of their careers.”

No matter what happens, the current contract negotiations will likely be Gamaldi’s last as Houston’s union president. He has publicly announced that he won’t run for reelection when his term expires in December 2021. “I just wanted to free up a little bit more time for my family,” he explained. Gamaldi said he’ll go back to being an ordinary police officer, although one friend suggested that he would be an effective politician—something Gamaldi pointedly declined to deny when I brought it up.

“I’m going to continue to be the vice president of the [Fraternal Order of Police], and I’m going to continue to be a voice for law enforcement,” he said, “whether some people like it or they don’t.”

The official police account of the January 2019 Harding Street raid started to unravel almost immediately, as did the angry spin that Gamaldi initially supplied. An internal affairs investigation would eventually reveal that the entire operation had been triggered by a 911 call from a neighbor, Patricia Ann Garcia, who claimed to have seen her daughter doing drugs at the Nicholas and Tuttle house. After receiving the 911 report, veteran HPD narcotics officer Gerald Goines secured a no-knock warrant to search the house by telling a judge that one of his confidential informants had purchased heroin there. But there was no informant, and the drug buy never took place—Goines appears to have simply made up these details. After the raid, police found small amounts of cocaine and marijuana but no heroin. (Garcia has been charged by the federal government with one count of “false information and hoaxes”; the case is awaiting trial.)

Two months after the deadly raid, with evidence of their misconduct mounting, Goines and Officer Steven Bryant, his former partner, abruptly retired from the department and began collecting their pensions. In August 2019, Harris County district attorney Kim Ogg charged Goines with two counts of murder and Bryant with tampering with a government record. The HPOU then stopped paying Goines’s legal bills—although it continues to fund Bryant’s defense. (“His case is slightly different from Gerald’s, and I’m just going to kind of leave it at that,” Gamaldi told me.) In July, Ogg charged four more narcotics officers with lying on police reports and stealing money from the division. The HPOU is also paying for their defense.

Gamaldi’s rhetoric continues to upset John Nicholas, Rhogena Nicholas’s brother, who volunteers as a fire chief and works part-time as an EMT in Louisiana. He remembers watching a segment on the CBS Evening News that night in January about a deadly raid in Houston. It wasn’t until the next morning that he learned that the couple killed in the raid were his sister and brother-in-law. “I’m not against police—I work for the Louisiana Department of Public Safety,” he told me. “But right is right, and wrong is wrong.”

GAMALDI RESPONDED THAT UNIONS SIMPLY ENSURE OFFICERS ARE GIVEN THE BENEFIT OF THE DOUBT. “DOESN’T AN OFFICER DESERVE TO HAVE THAT LITTLE BIT OF PROTECTION?”

According to family and friends, Rhogena spent much of her time helping others: driving friends to medical appointments, picking up groceries for housebound neighbors, and caring for Tuttle, who suffered from seizures resulting from a traumatic head injury he received in the Navy. “She did everybody else before she did herself,” John said.

The last time he spoke to his sister was when she called him a few weeks before her death, on his birthday. He’s been frustrated by the slow pace of the criminal cases against Goines and Bryant and by the paucity of information about the raid. More than anything, the family wants to clear the couple’s names from Gamaldi’s accusations. John still hasn’t received an apology. “The shoe’s on the other foot now,” he said. “They’re the scumbags and the dirtbags, the way I look at it.”

For his part, Gamaldi shows no sign of changing his tactics. In April, HPD officers shot and killed 27-year-old Nicolas Chavez, a father of three. Police were dispatched to the scene after 911 callers observed Chavez, who had a history of mental illness, wandering through traffic with a piece of rebar, repeatedly stabbing himself. As captured by body-worn cameras, officers soon arrived and spent the next fifteen minutes trying to subdue Chavez with stun guns and beanbag rounds before ultimately shooting him to death. Chavez fell to the ground after the first few shots, then was shot 21 more times while he was on his knees. Following a five-month internal investigation, HPD chief Art Acevedo fired four of the officers involved in the shooting, explaining that it wasn’t “objectively reasonable” to fire so many shots at a man who “was at his greatest level of incapacitation.” At a September press conference the police chief said, “I cannot defend that. And to anybody that wants to defend it, don’t come to this department. Because as long as I’m the police chief here … we will not allow people to use deadly force unless it’s objectively reasonable—and it just simply isn’t.”

That same day, Gamaldi spoke at a separate press conference held by the HPOU. Visibly upset and appearing to hold back tears, he called the firings “deplorable.” “This truly was a tragedy,” the union boss said, his voice breaking, “but the chief is now spreading that tragedy to four other families by unjustly firing these officers and using them as political fodder.” According to Gamaldi, Chavez was trying to commit “suicide by cop.” He believes Chavez’s shooting was justified because “he pointed a deadly weapon at officers: a Taser.” But video of the incident shows that the Taser had already been fired, rendering it harmless.

The four officers are appealing their terminations with legal representation from the HPOU; under the provisions of the union contract, if they win the appeal, they could get their jobs back. For Gamaldi, the firings were simply another example of America’s increasingly anti-police climate. Earlier in the summer, he told me that officer morale was the lowest he had ever seen.

“The officers that are older, you know, they can retire. They see the light at the end of the tunnel. Me, I’m, like, middle-of-the-road. I still got another ten years or so to do.” He said he feels the worst for younger officers. “They’re not gonna stay if this continues.”

It’s not unusual for labor unions to defend workers, even at the cost of public image, but I asked Gamaldi if he felt any responsibility for the rising hostility toward police, given his repeated defenses of officers like Goines and Bryant. Gamaldi responded that unions simply ensure officers are given the benefit of the doubt. “Doesn’t an officer deserve to have that little bit of protection?” he shot back. “Especially when we live in such a political climate right now, when a chief or sheriff will discipline someone just because.”

Ron DeLord, the union lawyer who told me George Floyd’s killing marked a turning point in American history, said a “tough reformation” lies ahead for the nation’s police departments. Gruff and plainspoken, DeLord has spent his career promoting and defending police unions, including publishing three books on the subject. He was the Austin police union’s chief negotiator during the recent contract fight. But even DeLord acknowledged that police reform was inevitable.

“The world’s going to change,” he said. “I know most of the major police union leaders around the country. I’ve talked with all of them in Texas. They know it’s coming.” For all the power police unions have accumulated, DeLord believes, it will be public opinion that ultimately decides the future of American law enforcement. “The police may bitch about it, they may get in a political argument about it, but in the end, if the city of Houston wants less police, they’ll have less police.”

This article originally appeared in the December issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “A Bad Cop’s Best Friend?” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Longreads