The federal agency caring for children apprehended at the border has begun sharing information with immigration officials about people offering to take custody of them, a sweeping change that a former official says will make it increasingly difficult to place children with their families—particularly those who are reluctant to get on the radar of an evermore aggressive immigration service. The Department of Health and Human Services, the agency mandated to care for these children, and the Department of Homeland Security signed a memorandum of agreement in April that called for the data sharing, and U.S. representative Beto O’Rourke, D–El Paso, said an HHS official told him Saturday that the information sharing began this week.

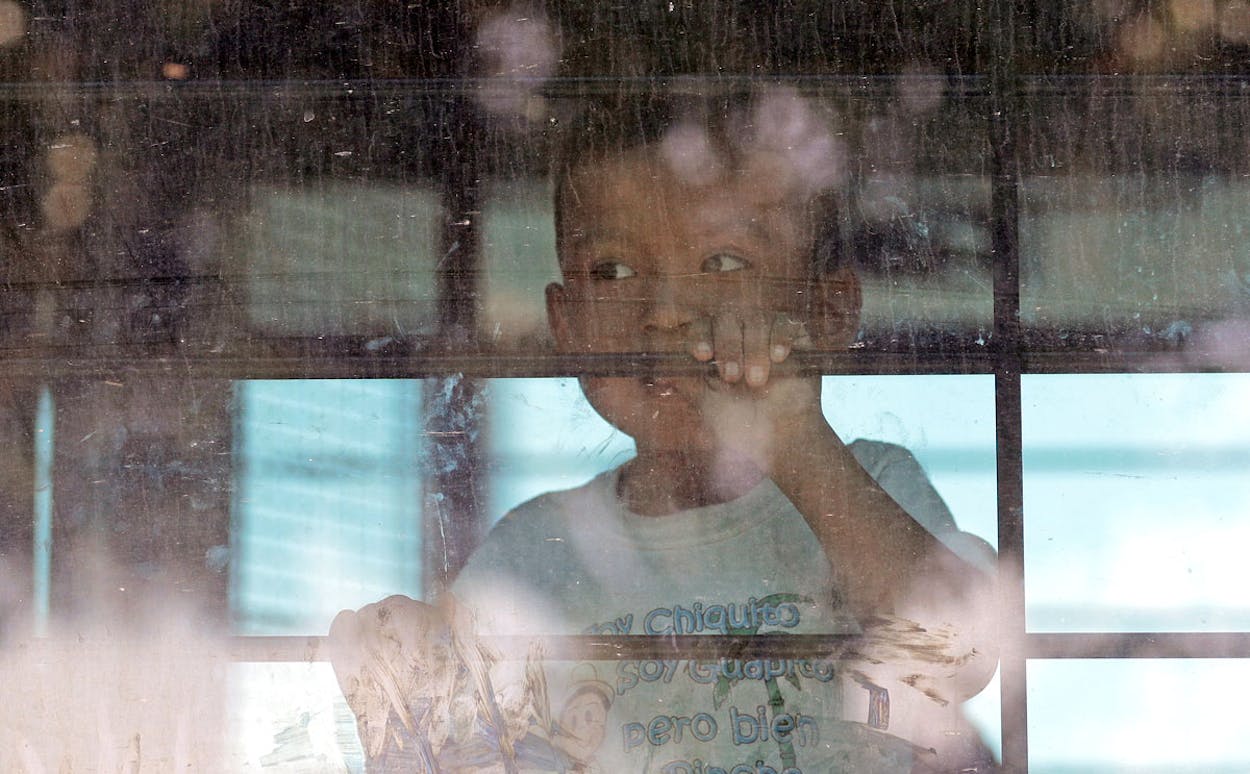

“There is a policy now on the part of our government for the Office of Refugee Resettlement to share information with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. That’s as new as four days ago. ORR, entrusted with the safety and placement of those kids who are without family, are sharing who those family members are with Immigration and Customs Enforcement,” O’Rourke said after he and other members of a bipartisan congressional delegation completed a tour of a tent city for near Tornillo, Texas, that is housing more than three hundred children who came to the border unaccompanied by an adult or were separated from a parent after the parent was arrested and are now classified as unaccompanied.

O’Rourke disclosed the agreement after touring the Tornillo facility with five other members of Congress, including U.S. representative Joaquín Castro, D–San Antonio, and U.S. senator Tom Udall, D–New Mexico.

The agreement calls for ORR to give ICE the names of potential sponsors for children in custody, as well as the names of all adults in the household. ICE then must request fingerprints from all adults in the household to review for criminal records. The unprecedented ICE access to ORR data will deter many potential sponsors who are undocumented or have family members without legal status, meaning untold numbers of children will remain in government custody rather than with their families, said Mark Greenberg, who oversaw ORR during the Obama administration. The current average stay of a child in detention has almost doubled in the past year, according to government records, and even that count only includes children released to a family member or sponsor—not those who are still detained months after coming into government custody.

“In the last administration we felt that it was important that the Office of Refugee Resettlement not be functioning as a partner in immigration enforcement because that wasn’t what the program was supposed to do,” Greenberg told Texas Monthly. “The program was supposed to provide shelter and services to children and help them get to a parent or other sponsor. And it would completely defeat those goals if parents and other sponsors were afraid to come forward because of immigration enforcement.”

The memorandum of agreement shows that “DHS and HHS see children as bait or suspects first, not children,” the Women’s Refugee Commission and National Immigrant Justice Center said in a June 6 background paper on the policy. “The MOA will undermine family reunification, the fundamental principle of child welfare law, by turning safe placement screening into a mechanism for immigration enforcement. This contradicts HHS’s goal of placement with the most appropriate caregiver.”

O’Rourke said he pressed an HHS official in the shelter on whether her department was sharing information with Immigration and Customs Enforcement about potential sponsors for the migrant children in federal custody. “She avoided the question at first but when I asked her for an answer, she paused, sighed, and said, ‘Yes, as of four days ago,’ ” he said.

The agreement, signed in April, calls for DHS and HHS to share information on “unaccompanied alien children” in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, the HHS agency charged with caring for migrant children apprehended at the border and, if possible, placing them with a relative or other sponsor so they could leave detention while their immigration cases are decided in court. That group includes children who arrived at the border without an adult and children who were separated from their parents by border agents. Children are often placed with family members already in the United States, including many who were undocumented. O’Rourke said the HHS official assured him that ORR would continue to place children with relatives regardless of immigration status but that ICE would have background information on everyone in the household.

Homeland Security officials didn’t directly address how agencies like Immigrations and Customs Enforcement and the Department of Customs and Border Protection were using the ORR. “This [memorandum of agreement] sets forth a process by which DHS will provide HHS with information necessary to conduct suitability assessments for sponsors from appropriate federal, state, and local law enforcement and immigration sources,” an official said in a statement. Health and Human Services officials didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

O’Rourke said he isn’t clear on what ICE will do with information it is collecting on potential sponsors, including whether they would use it to target people for deportation. But just the knowledge that ICE would have information on household members will create a chilling effect, O’Rourke and Greenberg said.

Greenberg also said the administration appears to be ignoring a key provision in the memorandum of agreement, which calls for parents to know quickly where their children have been taken. Many parents have said they aren’t getting information on where their children are. “That would raise an obvious question about an area where information sharing was desperately needed and whether they were doing that here,” he said.

The data sharing between DHS and ORR is one of several steps the administration has taken that has taxed the government’s capacity for housing immigrant children in its custody, said Jennifer Podkul, director of policy for Kids in Need of Defense, a Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit that provides legal representation to children in immigration court.

“So what they’ve done is, just before they got this incredible influx of separated children, they had two policies that are actually slowing down the release, the reunifications. One is this memorandum of understanding that you mentioned,” Podkul said. “The other is they now have a policy that started in June 2017 where the director of ORR has to personally approve the reunification of any child who’s in a staff-secure or secure facility. And that has also caused a bottleneck. There are a lot of children who are not being reunified.

“So it used to be that the average length of stay was about 30 days in ORR custody, because that’s how long it would take for them to find an appropriate sponsor and do the vetting and make sure it was a safe person. Now it’s up to 57 days,” she said.

“This is a self-created crisis, a self-manufactured visual crisis that the administration wants to use so that they can finish checking off some of their policy goals that they outlined way back in their executive orders” shortly after Trump took office, Podkul said.

Trump administration officials have previously dismissed concerns that they might be deterring families from seeking to reunite with children: “If somebody is unwilling to claim their child from custody because they’re concerned about their own immigration status, I think that, de facto, calls into question whether they’re an adequate sponsor and whether we should be releasing a child to that person,” Steven Wagner, the acting assistant secretary for the Administration for Children and Families at HHS, said in a call with reporters in May.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Beto O'Rourke