On a Friday morning in April, Dallas conservative talk radio host Mark Davis complained to his listeners about the crowded special election in North Texas’s Sixth Congressional District, which stretches southeast from downtown Fort Worth to past Corsicana. With 23 candidates—11 of them mostly like-minded Republicans—competing to take the seat vacated by the late congressman Ron Wright, even he, a politics obsessive, found it hard to keep up.

“It can make your brain turn to jelly,” Davis said. But he had a treat for his listeners: Michael Wood, the one Republican who had differentiated himself in the race, was coming on The Mark Davis Show that morning.

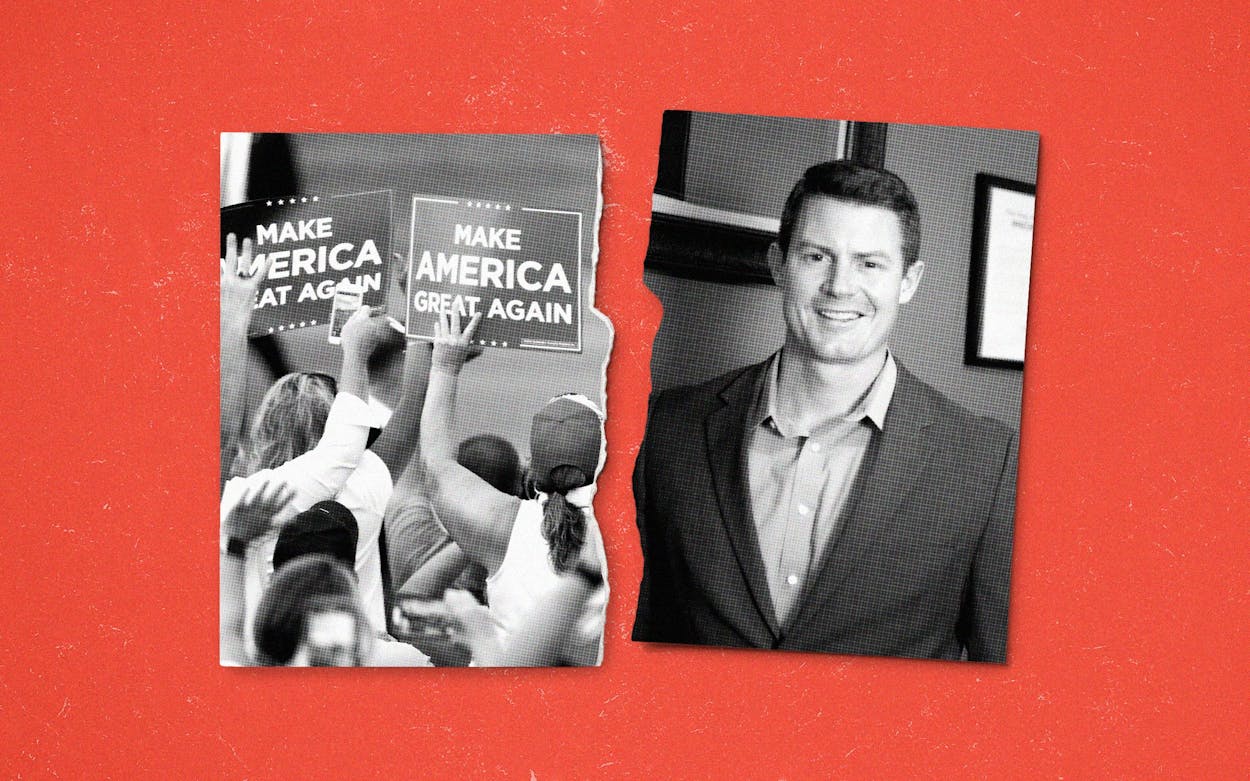

Davis walked Wood through his bona fides. A 34-year-old former Marine infantry officer, Wood lives in Tarrant County with his wife and four young daughters. A small-business owner, he observes all the usual pro-life, pro-gun, pro-oil articles of faith of his party, with one glaring exception—he really, really does not like Donald Trump.

Wood explained to Davis that he had voted for Gary Johnson, the Libertarian party nominee in 2016, because he didn’t trust Trump with the nuclear codes. But Trump got his vote in 2020, after the president exceeded Wood’s expectations and the Democratic party seemed to drift leftward. Wood would come to regret his vote.

“I think that all of his actions since Election Day, including on January 6, forfeited him the right to ever lead this party again,” Wood told Davis. Trump had duped patriotic Americans into committing treasonous acts, jeopardizing the peaceful transfer of power for the first time since 1860. “His Big Lie, saying that the election was stolen, really undermined the faith that the American people had in our system . . . It was one of the worst things an American president has ever done.”

Until this moment, Davis had held his fire. But Wood’s insistence that tens of millions of Americans had been deceived by a demagogue put Davis in attack mode. The candidate’s view of Trump supporters was “condescending to its core,” said Davis. “It’s your feeling that everybody that disagrees with you is just deluded. That is your feeling, Michael.”

But Wood was ready with a sizzling comeback: “This is one of the worst parts of what Trump has done to the right, is he’s turned us into a bunch of whiny little lefties. It’s all about ‘feelings.’ It’s all about ‘Well, you’ve got your truth; I’ve got my truth.’ ”

The exchange was tense, but when it was over, Davis told listeners just tuning in that they had missed something special. “That was some wonderful radio,” Davis said. “And if you are a Trump-hating Republican, Michael Wood is your guy. You have a voice. You have a candidate.”

It was a crystallizing moment for Wood’s short campaign, which launched March 1. For weeks he had attended one candidate forum after another with remarkably little pushback from rival candidates, some of them voluble Trumpers, or from those in his audiences, who mostly responded with respectful silence to what for many of them must have sounded like political apostasy. But here, on one of the biggest conservative media platforms in North Texas, he had mixed it up with a master, and his campaign had achieved a moment of political frisson.

Attention is what Wood needs if he is to differentiate himself in the huge field of those who hope to replace Wright, who died of COVID-19 in February. Where Wood has outdone all of his rivals is in garnering national media coverage with his depiction of the race as “the first battle for the soul of the Republican party” and his insistence that even as the former president is seeking to tighten his grip, there has to be someone to say, “We got to get away from this guy.” On Tuesday it was a positive spread in Politico. On Thursday morning, it was fourteen minutes alone on CBS’s digital streaming service. Even better would be if Wood could bait Trump into bashing him (though that’s not as easy now that the former president is banned from Twitter).

Brendan Steinhauser, the Austin consultant guiding Wood’s campaign, said the media attention builds momentum and boosts fund-raising, which has now surpassed $100,000—a fraction of the money raised by some of the other candidates but enough to target 100,000 voters, which he thinks may be double the number who turn out on Election Day on May 1. “If I can be successful in this endeavor, I can give Republicans the vocabulary for next year’s midterms,” Wood said.

It is a very big “if,” made remotely plausible only by the dynamics of a jungle primary, in which everyone, regardless of party, runs on the same ballot. If no candidate receives more than 50 percent of the vote, the top two finishers go to a runoff. Susan Wright, the late congressman’s widow, has a long history of political service and an extensive list of endorsements and is the most likely of the 23 to cinch a place in a runoff for TX-06. At least two other Republicans and three Democrats are regarded as having a better shot than Wood to join Wright in the runoff. (One recent poll, commissioned by conservative media outlet Washington Free Beacon, has Democrat Jana Lynne Sanchez leading with 16 percent, followed by Wright with 15 percent. Wood barely registered, with 1 percent.)

But Wood’s theory is that he can reach a silent minority of Republicans—he estimates as many as 30 percent to 40 percent—in the district who agree with him. They include the folks who sit through his remarks without clapping but come up to him afterward to get his literature: shy Trump skeptics not quite ready to out themselves. He hopes that he can harness enough of them, perhaps 20 percent of the total vote, to slip into the runoff. The Sixth Congressional District, he thinks, is primed for a tilt away from Trump. In recent years, it has grown a lighter shade of red. In 2012 Romney won by 17 percentage points. In 2016 Trump won by 12. In 2020 Trump’s margin had slipped to just 3 points, though Wright—who voted with Trump but nonetheless cultivated the persona of a genteel, old-fashioned Republican—beat his Democratic opponent by nearly 9 points.

Wayne Thorburn, a former executive director of the Texas GOP who is supporting Wood’s campaign, said the splintering of the vote and the distinctive character of a conservative anti-Trump appeal gives the candidate a narrow path to victory. Regardless, Thorburn said, Wood’s candidacy is part of a long-term project to pull the party back from the edge. “I think to accomplish that goal, one has to be willing to forgive and forget those who voted for Trump” in either 2016 or, like Wood, in 2020, he said.

Wood has won the endorsement of the Dallas Morning News and of Country First, the political action committee launched by Adam Kinzinger, the Illinois congressman who was among the ten Republicans who voted to impeach Trump in January. “I was impressed by his kind of standing alone in a crowd and saying what needed to be said,” said Kinzinger, who plans to campaign for Wood on April 26. But like Thorburn, he too emphasizes the long game, particularly the importance of persuasion. “In some people’s estimation, Donald Trump is the equivalent of the Second Coming of Jesus, and I’m not even kidding in that,” Kinzinger said. “If you believe that and somebody confronts you with the reality that this guy was bad, it’s tough to get through. But it’s that exact kind of leadership which is the only way we’re gonna get there, ever.”

To his supporters, Wood is trying to do what so many Never Trumpers just talk about: prove that the GOP’s future lies in a conservatism freed from Trump.

Wood tells a polished story about his path to victory, but the record of anti-Trumpers in the last few years suggests that he faces long odds, to put it mildly.

Southern Methodist University political scientist Cal Jillson argues that even in a field of 23 candidates, an anti-Trump Republican doesn’t have a large-enough constituency to win. “That’s not an electoral strategy. That’s not something that you take to the voters at this point, because most of the polling suggests that Republicans are still enamored of Trump and committed to him having a major role in the party,” Jillson said.

According to a University of Texas/Texas Tribune poll conducted in February, 85 percent of Texas Republicans viewed Trump favorably, and 81 percent didn’t think he had done anything to justify preventing him from holding office again.

Susan Wright told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram she’d be “honored” to have Trump’s support. State representative Jake Ellzey, who ran against Ron Wright in the 2018 GOP primary and is probably Wright’s most formidable Republican foe, told Politico the race “has nothing to do with President Trump.”

Two former Trump administration officials in the race—Brian Harrison, who served as chief of staff for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and Sery Kim, a former assistant administrator at the Small Business Administration—are seeking the former president’s endorsement. (Trump hasn’t endorsed anyone.) Most of the other Republican candidates lavish praise on Trump. Only Wood has been critical.

Texas may prove particularly tough terrain to wean the party faithful from Trump, even though he won by the state by a narrower margin in 2020 than in 2016, and by a far narrower margin than Mitt Romney in 2012 and John McCain in 2008. As Jim Henson and Joshua Blank of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas wrote in January, “Texas Republicans were pretty Trumpy before Trump,” striking all these same responsive chords with the party’s base: “the unabashed resentment of the political and cultural legitimacy gained by people of color, the unbounded vilification of political opponents, a white nationalist view of American identity, [and] the conviction that undesired electoral or policy outcomes are the result of incurably corrupt national institutions manipulated by uniformly feckless elites.”

Wood has enough in his background and bearing to invite his critics to view him, however unfairly, as in league with those elites. He left Midland, where he grew up, to attend New York University and, as he put it, “play around with left-wing politics for a while.” He studied economics and history, focusing on America’s founding, and picked up the habit of reading newspapers, bringing the New York Times with him on his first date with his wife, an NYU student, “in case it went sideways.”

He added, “But Greenwich Village, man, it really knocked the progressivism out of me over the course of four years.” He finished NYU a pro-life conservative and, ten days after graduation, reported to Quantico for Marine Officer Candidates School.

He is a National Review conservative rather than the Fox News variety. (He even did a regional fellowship with the venerable magazine a few years ago.) He didn’t know who Mark Davis was until he was booked to appear on his show. If he’s elected to Congress he would like to turn his office into a conservative think tank, as Paul Ryan, the former speaker and vice presidential candidate, did earlier in his congressional career.

Participating in an April 5 NAACP candidate forum in Arlington, Wood said that Republicans have sometimes used “disgusting” rhetoric likening the welfare state to plantation life. “I want to move away from that, and I want to move away from this idea that too many Republicans have that there’s real America, which is filled with white people and cows, and the rest of the country doesn’t matter,” he said.

The next night, he warned a standing room–only crowd of about a hundred at the Ellis County GOP headquarters, in Waxahachie, that if the party does not “move past Donald Trump,” Texas could go the way of Barry Goldwater’s Arizona and Newt Gingrich’s Georgia, both of which voted for Biden in 2020 and are now represented by Democrats in the Senate. “We are not a party of conspiracy theories. We’re not a party of QAnon,” Wood pleaded. “We can again be the party of Reagan. We can again be the party of Eisenhower. We can again be the party of Lincoln. That’s why I’m in this race. I respect you enough to tell you what I actually think to your face.”

Wood’s impassioned appeal drew tepid applause, along with a question from an older man in the crowd who had been listening intently to Wood, his arms crossed. “Who are you representin’? The people in this area, Texas, or are you more concerned about the USA?”

Wood assured the man that his family, among Stephen F. Austin’s original three hundred settlers, came to Texas “before there was a Texas.” Two of his four daughters were born out of state while he was in the Marines, and he’d had Texas dirt shipped to Indiana and North Carolina so they would be born on Lone Star soil.

“I love this state so much. But I love my country more; I do. I took a bullet for this country. Got two Purple Hearts. And, honestly, I don’t see any sort of conflict there,” said Wood, who served two tours of duty in Afghanistan and is now a major in the Marine Corps Reserves.

While very direct in his views on Trump, Wood told me when we first spoke last month, “I’ve developed a way of talking about it that I think doesn’t insult the people who have grabbed on to this guy for the past four years.” But as the exchange with Davis showed, Wood runs the risk of coming across as just another effete snob at odds with MAGA Nation. How do you tell someone he is in a toxic relationship without being seen as dangerous and disdainful; as the enemy? Wood’s appeal is to those who were never comfortable with Trump or have grown weary of him, are ready to move on, and are just waiting for a secret ballot they can cast for someone saying what Wood is saying.

When I last spoke with him, Wood acknowledged that the power of persuasion can go only so far. “I’m a realist, and I understand just how difficult this fight is gonna be,” he said. “I don’t regret at all—and I never will—deciding to do this, but there are moments when it feels like I’m just beating my head against the wall. This is just something I had to do. Nobody else is saying this, so I felt like I needed to say it.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Donald Trump