This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Bill Clinton won on election night, but the joy of Texas Democrats did not survive the sunrise. They awoke to the realization that for the first time since Texas joined the Union in 1845, a Democrat had won the presidency without carrying the state. George Bush beat Clinton by a solid three percentage points, or more than 200,000 votes. Farther down the ballot, Democrats lost an incumbent congressman, a railroad commissioner, two judgeships on the state’s highest courts, and four seats in the state Senate. In politics nothing happens in isolation; the last day of one election cycle is the first day of another. As the political calendar heads toward 1994, when Lloyd Bentsen, Ann Richards, and most statewide officeholders are up for reelection, Texas Democrats face the prospect of reduced influence in Washington and increased peril at home.

The question now is, What happened? Texas was by no means the lost cause for Clinton that it had been for Democratic candidates in the eighties. George Bush was no more popular here than he was anywhere else. Three weeks before the election, polls showed Clinton with a four-point lead in the state. But slowly, inexorably, Clinton began to slip, losing voters to both Bush and Ross Perot. By the weekend before the election, Bush had taken the lead with a media blitz.

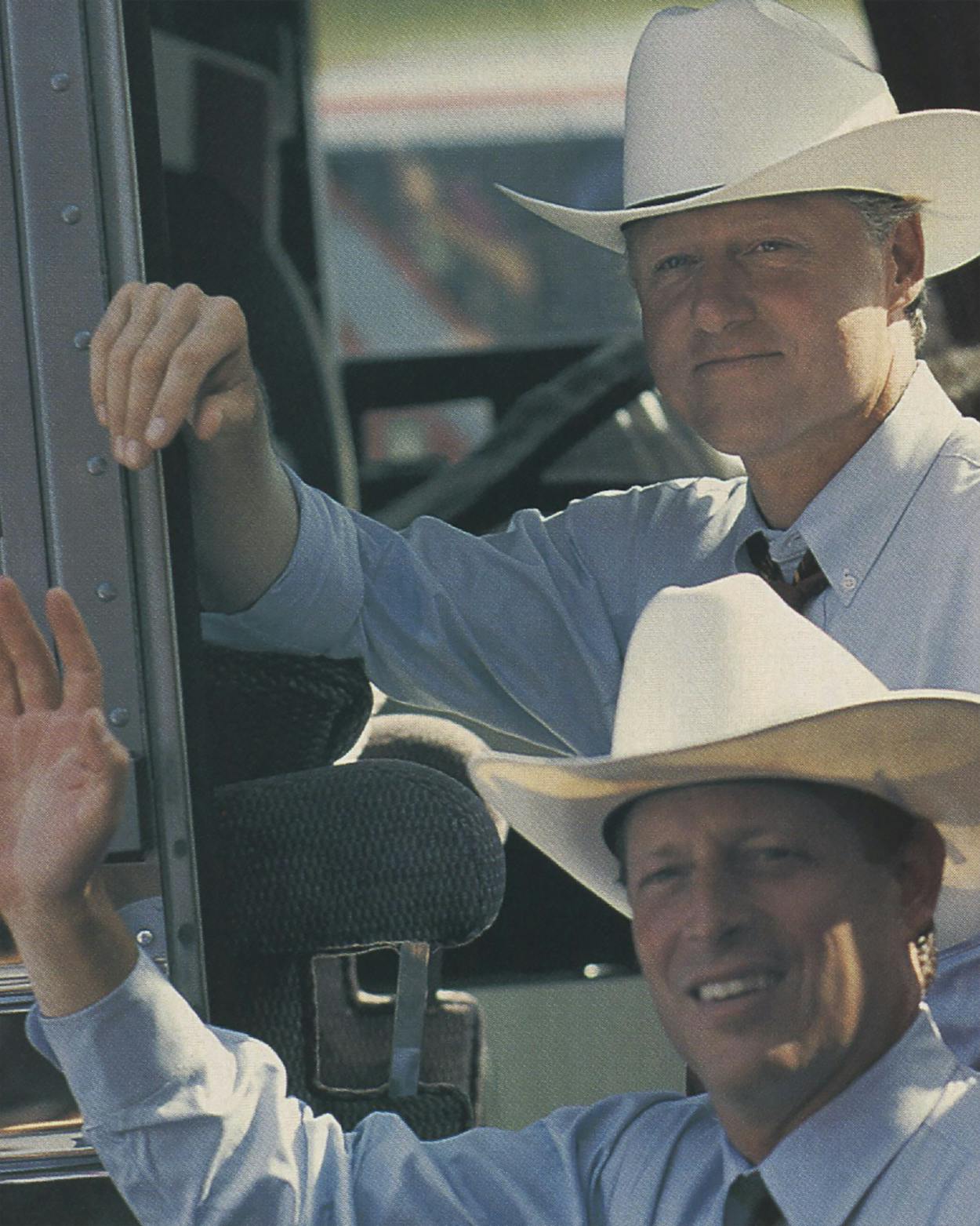

Yet Clinton did not lose Texas so much as surrender it. From the start, Clinton campaign strategists—especially political consultant James Carville—believed that Texas would end up voting for Bush. Their master plan for winning the election was to identify the states Clinton could win (31 in all, along with the District of Columbia), concentrate their efforts on them (they won every target state except North Carolina), and forget the rest. Texas was duly forgotten: It was the president’s home state and had voted 56 percent for Bush in 1988. The Clinton-Gore campaign didn’t spend a dime here to protect Clinton’s fragile lead—no TV spots, no mailings. The few commercials that did air were paid for with state and national Democratic party funds. Texans never saw the Clinton media campaign. Nor did they see much of Clinton himself after a late-August bus tour through Central Texas.

The Clinton strategy drove top Texas Democrats crazy. From Ann Richards and former lieutenant governor Bill Hobby to consultants like Roy Spence of Austin’s GSD&M advertising agency, they all kept sending messages to Little Rock that Texas could be won—if only Clinton would compete. The word kept coming back that Texas was on a list of states to watch. That hardly satisfied the Texans. “Do you know where Bill Clinton is today?” Hobby exploded to friends one day shortly before the election. “He’s in Colorado. Colorado has eight electoral votes. Hasn’t anyone told him that Texas has thirty-two?”

But Carville never wavered. Regardless of what the polls and the Texans were saying, he was certain that no matter what Clinton did, Bush would do more. But Bush couldn’t take Texas for granted, because Perot was taking votes away from him. So the Clinton plan was to run a low-budget old-fashioned organization campaign and keep the race in Texas close enough to make the president spend time and money here. Democratic operatives kept putting out the word that Clinton was about to make a big effort in Texas. “It was a rope-a-dope tactic,” said Austin-based Democratic consultant George Shipley, referring to Muhammad Ali’s description of how he won a famous fight against George Foreman: Lie back against the ropes and let Foreman expend his energy throwing punches the ropes would absorb. In the end, Bush spent more than $4 million to win the state—money that was badly needed elsewhere. “I didn’t win Texas,” sighed a Clinton staffer assigned to the state, “but I guess I won Georgia.”

Many Texas Democratic leaders thought that more emotion than logic lay behind the Clinton campaign’s attitude toward Texas. As a consultant, Carville had directed three races here: Lloyd Doggett’s 1984 Senate campaign against Phil Gramm, Fred Hofheinz’s 1989 challenge of Houston mayor Kathy Whitmire, and Jim Mattox’s 1990 Democratic primary battle with ann Richards. All ended in landslides—against Carville’s candidates.

Clinton’s neglect changed the dynamics of the election in Texas by failing to create any Democratic momentum. The absence of a viable Clinton campaign was most noticeable in South Texas, where the Hispanic turnout was disappointing. A big vote in South Texas is the indispensable element in a Democratic victory, but in most counties south of San Antonio, the turnout fell far below the statewide average of 72 percent: 59 percent in Cameron County (Brownsville), 58 percent in Hidalgo (McAllen), and 47 percent in Webb (Laredo). Bush broke the 30 percent barrier in all three of these big counties, and a strong showing by Perot in Cameron held Clinton under 50 percent. Clinton came out of South Texas with only a 71,000-vote lead—more than 100,000 votes short of the margins that victorious Democratic Supreme Court candidates Jack Hightower and Rose Spector piled up over their Republican opponents.

With no help from Clinton, the Democrats were forced to rely on the old-time religion in South Texas—party loyalty and get-out-the-vote drives. But mechanics without message did not work. The old system of relying on courthouse politics and “street money” for political patrones didn’t motivate an increasingly diverse Hispanic electorate. As more Hispanic voters achieve middle-class status, media messages and bread-and-butter issues (the economy, education, crime) are getting to be just as important in South Texas as anywhere else.

Clinton’s lead in South Texas disappeared under an avalanche of votes from traditional Republican strongholds—the suburbs and the Panhandle. Collin County (Plano) had an enormous 84 percent turnout that gave Bush 36,000 more votes than Clinton, who received an embarrassing 19 percent of the vote. (It could have been worse: Perot captured 34 percent, leaving just 47 percent for Bush.) Clinton lost the Panhandle by 78,000 votes, a two-to-one margin, but won East Texas (where Jimmy Carter led by 74,000 votes in 1976) by only 17,000. He virtually broke even in the six big urban counties but lost the next group of nineteen—the suburbs, the mid-sized cities like Lubbock, and a few South Texas counties—by 111,000 votes. In the end, Clinton polled fewer votes than Lena Guerrero, who was routed in her race for railroad commissioner after she lied about her academic record.

Now Texas Democrats must pay the price for Clinton’s neglect. The once-conventional wisdom that a winning Democratic coalition had to include Texas was no mere exercise in political theory. It was a major reason why John Kennedy made Lyndon Johnson his vice-presidential running mate in 1960 and Michael Dukakis did the same with Lloyd Bentsen in 1988. It was constantly cited by Texans in Congress to win such concessions as funding for the supercollider and the space station. Now that Democrats in Congress (and in the White House) have seen that they can win without Texas, those old entreaties won’t work anymore. Texans will have a harder time being heard in Washington.

In Texas the tab has already come due. The Democrats lost close races up and down the ballot that they should have won—starting with Pete Benavides’ defeat on the Court of Criminal appeals and going through local judicial races in Harris County. They failed to plug the down-ballot leaks that started in 1990, when state treasurer Kay Bailey Hutchison and agriculture commissioner Rick Perry won statewide races for the GOP. Republicans know that they can win if they have good candidates—and they know that the Democrats can’t win if they have bad ones, like Guerrero and Supreme Court judge Oscar Mauzy. Recruiting GOP candidates can only get easier as the party’s likelihood of success increases.

The Democrats still have two formidable figures at the top of the ticket in 1994—Lloyd Bentsen, if he runs for reelection, and Ann Richards, if she retains her spectacular approval ratings. What the Democrats have lost over the years is the assumption that their incumbents will win unless something goes terribly wrong. In the Reagan years the party label became as much of a burden as a blessing. Bill Clinton had a chance to fix that with his message that the party had changed. But Texans never heard it. Instead, the conscious rejection of the state by a Democratic presidential candidate gave credence to what Texas Republicans have long been saying: The national Democratic party has no place for—and is no place for—Texas.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Bill Clinton