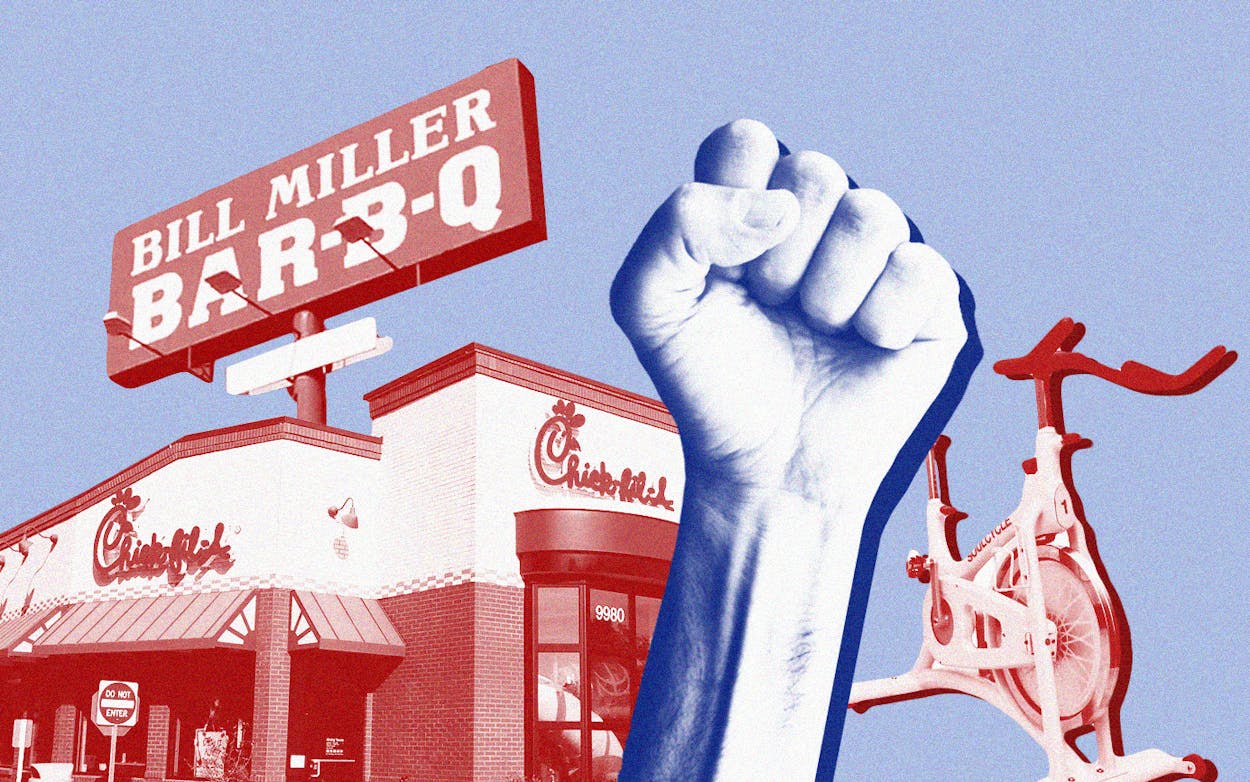

Last week, Joaquin Castro tweeted a list of big-money individual donors to Donald Trump’s campaign from his hometown of San Antonio. In the tweet, Castro singled out San Antonio business owners, including Balous Miller of Bill Miller Bar-B-Q; Christopher Goldsbury, whose Silver Ventures owns the revitalized Pearl Brewery hotel and retail complex; and Phyllis Browning, owner of a leading real estate agency.

Almost immediately, Castro was accused of “doxxing,” or endangering the safety of the people he named. But the outcry was overblown. The donation information is publicly accessible and Castro’s tweet didn’t include addresses or any other identifying information other than the names and businesses of those on the list. Rather than an act of doxxing, Castro instead seem to be suggesting that his followers take action by reconsidering where they spend their money.

Sad to see so many San Antonians as 2019 maximum donors to Donald Trump — the owner of @BillMillerBarBQ, owner of the @HistoricPearl, realtor Phyllis Browning, etc.

— Joaquin Castro (@Castro4Congress) August 6, 2019

Their contributions are fueling a campaign of hate that labels Hispanic immigrants as ‘invaders.’ pic.twitter.com/YT85IBF19u

The conversation around boycotts has taken on new energy as America has grown more politically divided. Conservative fans of Sean Hannity smashed their Keurig coffee makers in 2017 to protest the company pulling its ads from Hannity’s show; longtime NFL fans vowed to quit watching football games after players took a knee in protest of police brutality, sending the league into crisis mode.

On the other side of the political spectrum, liberals have taken aim at the Miami Dolphins—as well as fitness brands SoulCycle and Equinox, also owned by team owner Stephen Ross—after Ross hosted a $250,000-per-plate lunch to raise money for Trump’s 2020 campaign. In March, the San Antonio City Council voted to oust Chick-fil-A from the airport, in part because the fast-food chain’s owners have a history of funding anti-gay causes, prompting Greg Abbott to sign into law a bill prohibiting Texas cities from taking “adverse action” against organizations based on their donations. It became known as “the Chick-fil-A bill.”

Then, last week, Chick-fil-A struck back at San Antonio, announcing that it would be removing the city from the list of potential hosts for its annual convention in 2022. The company claimed the decision was unrelated to the airport fight, instead citing “the logistics for a group our size” as the reason the Alamo City was no longer being considered. (It’s unclear how the city’s logistics failed to satisfy the company’s need to host approximately 6,500 people when San Antonio has hosted significantly larger events like the NCAA men’s basketball Final Four.)

If Chick-fil-A was attempting a low-key protest against the San Antonio City Council, it would be understandable—and also symptomatic of the times. We’re firmly ensconced in the era of the boycott, in which people who’ve long been courted for their consumer dollars feel increasingly empowered to use them to make political points. Boycotts aren’t new, of course. During the civil rights era, activists organized boycotts of segregationist businesses; in the eighties, a global movement helped bring about the end of apartheid by boycotting South Africa; and in the early days of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, supporters of the war pushed the Dixie Chicks off the airwaves. But in the age of Trump, the cultural dynamics around boycotts have changed. Whereas boycotts in earlier eras were typically expressions of collective action that required a galvanized public to give them power, boycotts driven by social media are extremely easy to declare, and much more rooted in the participants’ sense of their individual consumer power, and their ability to communicate directly with the target of their ire.

Individual consumer power isn’t particularly relevant to a boycott, though. One guy tweeting to Nike that he’s never going to buy their sneakers anymore doesn’t trouble the company; even if the company assumes that he represents a dozen more people who feel the same way, they can also assume that there are just as many who are going to seek out Nikes because they want to wear the same shoes as one of their sports heroes.. The boycotts that have been successful in the age of social media and hyper-polarization have been built around organized, collective action like the “Sleeping Giants” campaign, which targeted corporations that spend advertising dollars with far-right media companies. The line between individual and collective action on social media is a blurry one, though, which means that we’re seeing more folks calling for boycotts, and less impact from most of them.

It’s also sometimes difficult to parse exactly how it all works. Let’s look at this tweet from San Antonio-based actor Armie Hammer.

Hey, while everyone seems to be on this Equinox thing, it might be a good time to mention that one of Trump’s largest financial contributors is the chairman of Marvel Entertainment (Isaac Perlmutter)….. jussayin.

— Armie Hammer (@armiehammer) August 9, 2019

It’s unclear from the tweet if Hammer is calling for a boycott of Marvel, rising to the defense of Equinox, or trying to make a point about the futility of boycotts generally. It could be all three. But if he’s suggesting that liberals should boycott Marvel, all that would do is put them in the same company as their conservative counterparts, who frequently have Marvel parent company Disney in their sights as a boycott target. Dolphins fans on the right frequently condemn outspoken wide receiver Kenny Stills for taking a knee during the national anthem, while fans on the left protest Ross’s fund-raising activities for Trump—which means that, even if the company’s bottom line were to be affected by a boycott, it’d be a heck of a challenge to fully understand which group it needs to listen to.

Meanwhile, Bill Miller Bar-B-Q will probably survive Joaquin Castro. In a mirror image of the Nike effect, Trump supporters have rallied around the chain, and Twitter, where this whole thing started, is awash in photos of cars lined up at the restaurants’ drive-thru lines.

https://twitter.com/MamaGill10/status/1159576051548401664

https://twitter.com/TamieJMcDonald/status/1159081704583303168?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1159081704583303168&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.theepochtimes.com%2Fcastros-trump-donors-list-leads-to-booming-business-for-texas-bbq-chain_3036961.html

This is a side effect of politics by boycott, and it’s creating a weird culture. Chick-fil-A endures despite not being in the San Antonio airport by catering to folks who do share its leadership’s views. Americans are already divided over their politics, where they live, where they get their news. Now, in America’s divorce, conservatives get custody of Bill Miller and Chick-fil-A, while liberals get Nike, Harley-Davidson, and the NFL. The companies at the greatest risk are those like SoulCycle and Equinox, who are in the process of getting disowned by the Democratic-leaning affluent city-dwellers who currently claim them, without a plan for how to appeal to the other side.

It’s long been true that our tastes are fairly reliable indicators of individual political leanings. Facebook’s advertising model depends in great part on identifying where people’s seemingly unconnected interests overlap. (That’s also the method that Cambridge Analytica used to help the Trump campaign target voters it could either win over or persuade to stay home.) And the correlation between lifestyle and politics is still active. In last year’s mid-terms, 70 percent of House seats that flipped from Republican to Democrat were in districts that had a Whole Foods. But these days, where we like to eat and shop doesn’t just tell us about our personal politics—in the boycott era, our politics also increasingly dictate our tastes.

That’s good for Bill Miller Bar-B-Q, if its new customers stick around. But it’s bad for anybody who wants to feel like they are part of the same country, and the same culture, as the people they disagree with. When Texans can’t even agree about Willie Nelson anymore, we’re a divided people. Neither Joaquin Castro, the San Antonio City Council, Chick-fil-A, or Balous Miller started it, but they’re all part of why it’s happening.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Joaquin Castro

- San Antonio