This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

For one poignant moment on election night, it was 1990 all over again. As the crowd at Austin’s Capitol Marriot celebrated George W. Bush’s growing lead over Ann Richards in the governor’s race, a TV reporter found a willing subject in the audience to interview and the camera focused on the familiar face of Clayton Williams. The man whom Richards vanquished in 1990 delivered a few homilies, but then, as is his wont, he just couldn’t stop himself. Bush, he predicted, would lead Texas away from—guess what?—socialism. Oh, Claytie, Ann Richards needed you again, and you weren’t there.

Instead, November 8 was a day of a lifetime for Texas Republicans. After winning an eight-point victory in a governor’s race that was supposed to be too close to call, they now have nationally known figures holding the three most important offices in the state: Bush and senators Phil Gramm and Kay Bailey Hutchison. With the defeat of Ann Richards, the star factor in Texas politics now favors the Republicans.

The GOP also made inroads farther down the ballot. It has all three railroad commissioners and a brand-new majority of the Texas Supreme Court. The party won three swing seats in the state Senate and needs only two more for a majority; it picked up a seat in the state House, for a total of 61 out of 150. It shows how far Republicans have come that a gain of two U.S. House seats (to 11 out of 30) was regarded as a disappointment.

The big question in the wake of Bush’s victory is whether the Republicans’ current momentum is likely to be transitory or long lasting. The indicators are favorable for the GOP. Although Bush won on a historic day in national politics when Republicans took control of both houses of Congress, nothing about the Texas vote suggests that Texans were driven by fury at President Bill Clinton. The statewide turnout, 50.9 percent, was four points below the prediction of state election officials. Virtually the same percentage of the electorate voted this year as in 1990 (50.6 percent). Nor was the turnout unusually heavy in traditionally Republican areas. Collin County, a GOP suburban stronghold north of Dallas, had a 58.8 percent turnout in 1990 compared with 56 percent this year.

Population growth, not anger, explains the Republicans’ advantage. Let’s go back to Collin County. Despite the lower percentage turnout, the county grew so fast that 26,000 more votes were cast there this year—and George W. Bush got 80 percent of them. Clayton Williams won the county by 13,000 votes in 1990; Bush won it by 31,000.

Statewide, Richards actually received 90,000 more votes than she did in 1990. But Bush outperformed Claytie by more than half a million votes. Much of the growth in Texas has occurred in Republican areas of big cities and their suburbs. Democratic South Texas is growing too, but it lags behind the rest of the state in voter registration and participation. The population growth doesn’t show up in the vote. In Webb County, which includes Laredo, a 30.6 percent voter turnout produced only 500 more votes for Richards.

Do the numbers mean that the race was unwinnable for Richards from the start? Bush’s strategists certainly didn’t think so. They were worried that Richards would beat Bush to the punch, establishing her strengths and his weaknesses before he could get a chance to do the same to her. Richards, they believed, had access to more money than Bush did, and if she had started a spending war in the spring or summer, Bush would have had to decide whether to respond and risk running out of money or husband his resources for a future counterattack.

Richards did nothing, and so it was Bush who defined the race. Her campaign had no battle plan, no theme, no message. She said little about her record—which was the best of any governor since John Connally—and even less about what she wanted to do in her next term. The Richards camp seemed to lack confidence. They used focus groups incessantly, trying to figure out the mood of the voters, while Bush’s strategists operated more on instinct, using only one set of focus groups. Richards wanted just one debate, a limit to which the Bush strategists were thrilled to agree.

The Bush campaign had a game plan and stuck to it. Bush would be the candidate of change, the magic word in the nineties; attack Richards on nonpartisan issues of public discontent (crime, welfare, education); soft-pedal the generic Republican issues like taxes and spending; and avoid purely personal attacks. Mike Toomey, a wonkish former Houston legislator turned business lobbyist, helped form teams to develop Bush’s policy positions. Bush learned his lines and stuck to the message. After the votes were counted on Election Day, Toomey exulted that the race had come down to “ideas over personality.”

Richards’ strategists kept hoping for Bush to commit a fatal gaffe—that was as close as they came to having a strategy—but Bush remained disciplined. As soon as Richards began using negative commercials criticizing Bush’s record as a businessman, he countered by accusing her of making personal attacks instead of talking about the issues. The Bush campaign was as good as the Richards campaign was awful.

In the end, Richards fell victim to her biggest political weakness: She overvalues loyalty and undervalues talent. She got her start in politics as a county commissioner, and as governor she still acted like a courthouse politician, surrounding herself almost exclusively with old pals. Right from the start, her campaign staff seemed to recreate the shortcomings of her gubernatorial staff—namely, that they weren’t very good at talking to anybody except each other. It was Richards’ fate, and fault, that she was let down by her own people.

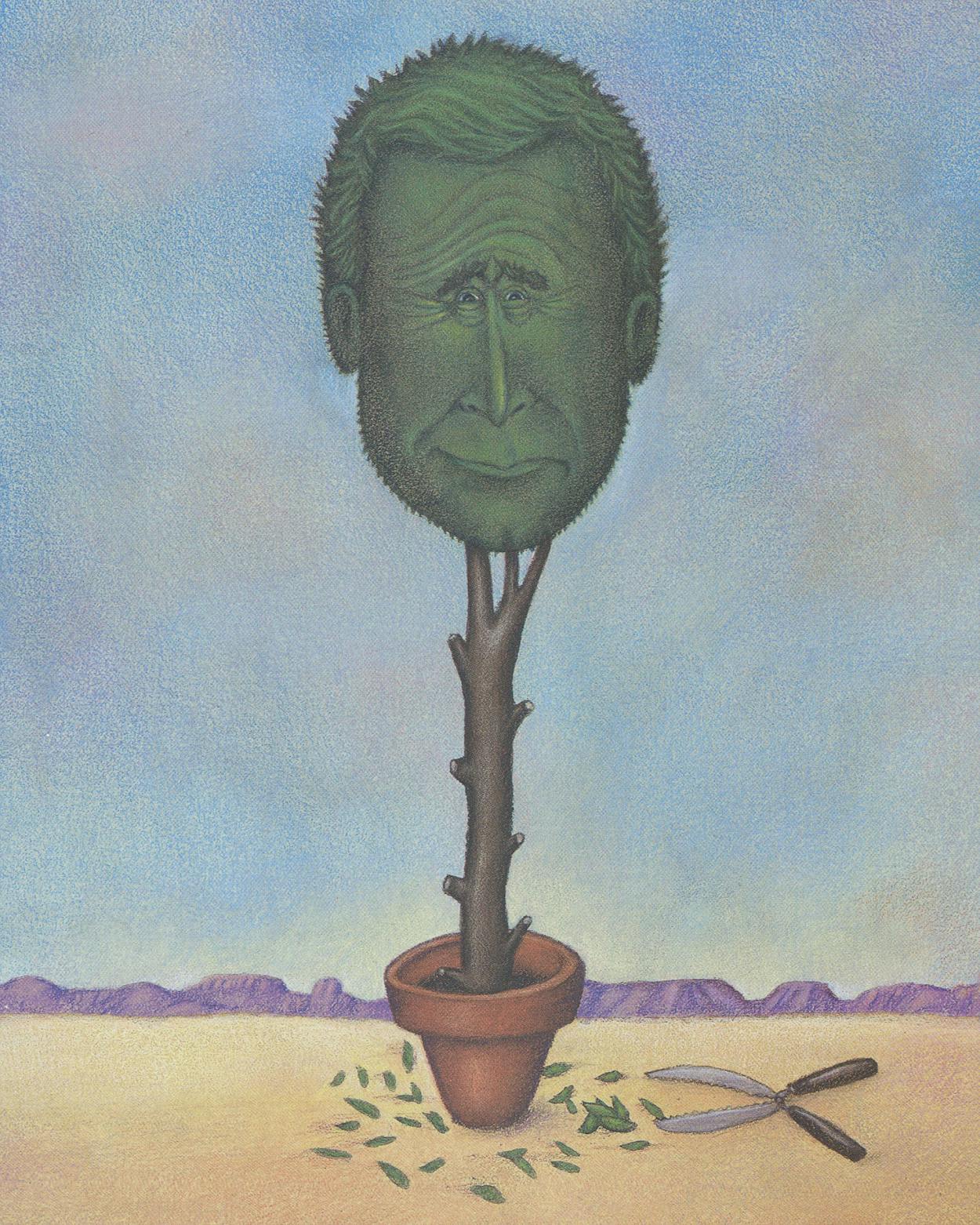

Now it’s George W. Bush’s turn, and he has his own pitfalls to worry about. Richards didn’t win may votes with criticisms of Bush’s career as a businessman, but she did paint a troubling picture of a man who has consistently benefited from very friendly deals. A lot of people will be watching to see if the habit follows him into the governor’s office. He must decide how much he owes the religious right and the Bubbas in East Texas. Richards’ veto of a handgun referendum cost her dearly in Bubbaland; don’t be surprised if a bill giving Texans the right to carry handguns becomes a law. Bush must decide how partisan to be—and he will be under the pressure to be highly partisan on issues like the budget. He is in a position to be a pivotal figure in Texas history, the person who leads the Texas Republican party out of its brash Phil Gram adolescence into maturity. But first he has to solve the same problem in Austin that Republicans now face in Washington: How to govern with a party whose elected officials hate government.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George W. Bush

- Ann Richards