This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Does this world leader sound familiar? He’s bald, he’s younger than his predecessors, and he’s a newcomer. Five years ago, nobody had heard of him. The regime he heads owes its origins to a 1917 revolution. But the revolution is sick. It has throttled the free exchange of information and opinion. It has given a monopoly of power to a stultified party. It has spawned corruption, speculation, and a thriving black market. State industries are bloated and inefficient, and some of them, the new leader says, will have to be sold to private interests, even to foreigners. The whole country, in the leader’s view, needs to submit to “modernization.” Mikhail Gorbachev? Yes, but also—at least according to correspondents for the American press—Carlos Salinas de Gortari, Mexico’s president.

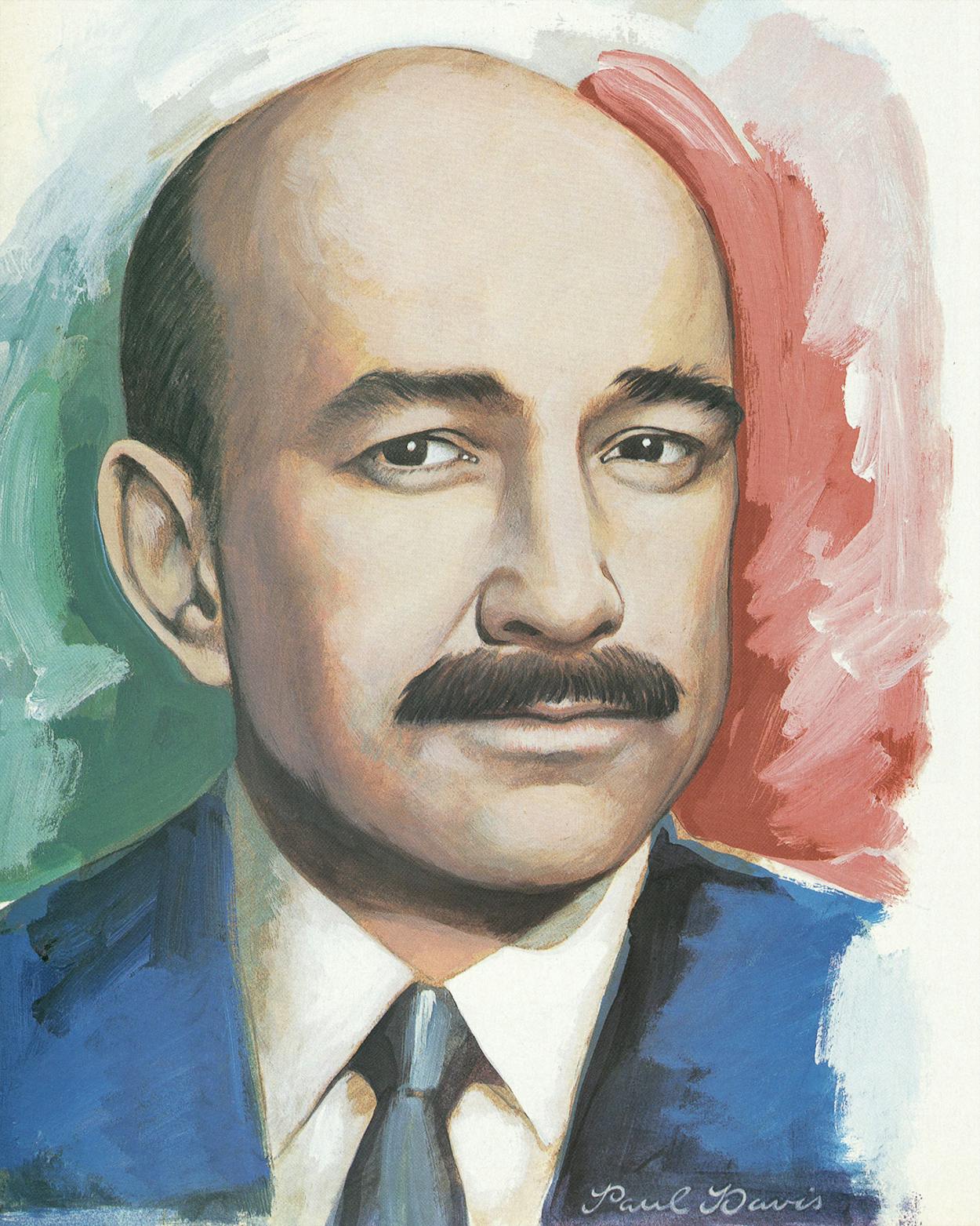

President Salinas has been making journalists’ lists of heroes this year. In a February New Republic editorial titled “a Gorbo for Mexico,” writer Morton Kondracke named Salinas to a pantheon of foreign heroes, including Lech Walesa, Corazon Aquino, and Benazir Bhutto. The list also included Deng Xiaoping. Kondracke’s list, as the June events in Beijing made clear, was a yardstick of American optimism about foreign affairs.

In January, when Salinas jailed the chief of Mexico’s petroleum workers union, Newsweek said, “In one stroke Salinas all but shattered the image of weakness that has dogged him.” The National Review dubbed him “Bald Man on a Horse.”

Texas commentators have fallen into fine. In July, when Mexico’s ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI)—the party of Salinas—recognized an opposition win in a gubernatorial race for the first time, the Corpus Christi Caller-Times headlined its editorial PRESIDENT OF MEXICO KEEPING HIS PROMISES. The Houston Post enthused that Salinas “is the best hope for democracy and economic health in Mexico.” The Dallas Morning News billed him as “an individual who long ago ceased running for office and is now running for history.”

Salinas is admired in the U.S. because Americans see him as he sees himself: as the man history has called on to save Mexico from decline. If he can’t save the country, according to the standard line, misery and turmoil—perhaps even another revolution—could result. On the other hand, if he gets his way, Mexico could become a prosperous manufacturing center, a democratic Korea or Taiwan. The stakes are high. Payment of Mexico’s mammoth foreign debt, owed mostly to American banks, could depend on the outcome.

But American praise of Salinas and his program isn’t echoed on the other side of the Great River. The independent press there is skeptical of Salinas. The country’s most thorough newsweekly, Proceso, and its most respectable newspapers—the leftish La Jornada, the centrist El Universal, and the rightist El Norte—have all stood aside while our press has serenaded Salinas. Americans who reside in Mexico share their misgivings. “I have seen Batman, and his name is Salinas. I almost believe. What spoils it are the cheap detective stories,” quips a columnist from the Mexico Journal, the weekly magazine of Mexico’s Anglo-American community. Salinas, like George Bush, is more popular abroad than at home. But most home-country readers do not evaluate presidents by headlines. They judge leaders by changes in daily life—changes that foreigners don’t see. From inside Mexico, Salinas’ shining deeds seem tarnished by the very evils they’re supposed to combat.

Recipe for a Chilango

Carlos Salinas is an exceptional man by anybody’s account. But in Mexico his outstanding intellectual traits do not compensate for other deficiencies. Salinas is a short, thin, hyperactive fellow with big ears who was nicknamed the “Atomic Ant” by Mexican journalists. He is not suave and handsome like Mexico’s last popular president, Adolfo López Mateos (1958–64). Because he has no box-office appeal, Salinas can never be a John F. Kennedy or a Santa Anna, a leader who woos a nation with his good looks and personal charm. As if to make up for his lack of physical stature, Salinas is a world-class horseman, a six-mile-a-day jogger, and a sometime practitioner of martial arts, but that makes him only what Teddy Roosevelt would have been without the Spanish-American War.

If Salinas is to become a great Mexican leader, he must win a popular following with his personality traits or his political program. He faces an uphill battle because he owes his office not to public acclaim but to a former president whose chief characteristic was ineffectiveness. Even members of the PRI were not waiting for Carlos Salinas to become president in the way that liberal Democrats waited for Robert Kennedy to succeed Lyndon Johnson. Most of them had never heard of Carlos Salinas until Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado handpicked him for the presidency. “Carlos Salinas was selected because of President de la Madrid’s conviction that the cronyism of Mexico’s older generation of politicos is responsible for the nation’s present predicament,” an American commentator speculated after the nomination. That explanation is plausible, but no one can know for sure. Mexican presidential selections have never been publicly explained.

Before Salinas took office as president on December 1, 1988, his only significant public role had been as a numbers cruncher—he was the secretary of Mexico’s Ministry of Planning and Budget during the De la Madrid administration. He had never run for public office. On the hustings, Salinas made a better appearance than his grunting predecessor, but he was no great shakes as a campaigner—his speeches tend to be stiff and formal. He’s reportedly no better in one-on-one meetings. “His attitude is one that says, ‘I know what I’m talking about, and you don’t.’ It’s the arrogance of an academic,” an American reporter says.

Nor is Salinas a Benito Juárez or an Abe Lincoln, a homely, plainspoken man who wins his way on the purity or populism of his sentiments. He was not born in an adobe cabin, but when he speaks to commoners he often wears jeans instead of suits. Salinas comes from the circles of the prosperous and prominent. His father is a senator from Nuevo León. His mother is a founder of the Mexican Association of Women Economists. Because his parents pursued public-service careers, Salinas was born in Mexico City, not in the family’s home state of Nuevo León—and that makes him a chilango.

Chilangos are so unpopular in the rest of Mexico that recently, in protest of the capital city’s grip on local party affairs, Tijuana PRIistas circulated this recipe for chilangos: “Over a very low flame mix one hundred grams of know-it-all with one hundred grams of presumption. Add one hundred grams of authoritarianism and another hundred grams of laziness. But be careful: Everything must be perfectly measured, because if you add one milligram too much, instead of producing a chilango, you’ll come out with an Argentinean.” Argentineans, it should be added, are unloved in Mexico because they have a reputation for arrogance, especially racial arrogance. They point out that they are white whereas other Latin American peoples are largely from Indian or African stock.

Like Yale graduate Bush, Salinas carries the seal of competency but also faces the popular resentment and distrust that come with an Ivy League education. In the late sixties he was the favorite student of future president De la Madrid at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. Salinas spent most of the balance of the decade at Harvard, where he earned master’s degrees in public administration and political economy and a Ph.D. in government. De la Madrid was also a Harvard graduate, but perhaps because he was closer in time to the nationalist and populist traditions of Mexican politics, he downplayed his foreign education. Salinas is strident where De la Madrid was cautious: Not only does he speak English freely but he has also placed other Ivy Leaguers in the cabinet and the Chamber of Deputies (Mexico’s congress), alongside old-line Mexican politicians with shady reputations. No one knows if Salinas sees Japan as the model of Mexico’s future, but Japanese, not English, will be his children’s second language. They attend a private school operated by Mexico City’s Japanese community, and Salinas and his family make annual pilgrimages to Tokyo. Were Salinas not past 40 (he’s 41), he would be pegged as a “junior”—a Mexican analogue for yuppie. He is an elitist in a country of populists and an internationalist in a country notorious for nationalism.

The Economic Program

Carlos Salinas is most often identified as a neoliberal political economist. His approach to the Mexican economy, shared with De la Madrid, is “a smaller government is a stronger government.” His anti-inflationary, free-market enthusiasm has won him widespread praise in the U.S.

American editorialists laud Salinas partly because he has pledged fiscal responsibility. Under the leadership of De la Madrid and Salinas, Mexico has become a docile debtor. Unlike Peru and Brazil, it has declared neither moratoriums nor suspensions on its payments. But Mexico is enlarging its internal debt, and it isn’t paying off its external debt, as Americans commonly believe. In 1982, when De la Madrid took office, Mexico’s foreign debt totaled some $84 billion. Today it stands at $107 billion. One reason the foreign debt has increased is that Mexico’s chieftains have wheedled new loans to tide the country over while the terms of payment are renegotiated. In the year since Salinas’ election, the Mexican government has finagled four such loans, for some $7 billion. Thus far, Salinas is paying today’s debt with tomorrow’s indebtedness.

When Salinas came home from negotiations in Paris last July with a package of alternatives for paying the debt, he went on national television to tell his countrymen, “We can now leave behind the crisis. As a result of negotiations, we will be better off each day.” He also described the debt agreement as one that could heighten Mexico’s international leadership, saying that “Mexico has opened the way for other nations with similar problems.” But the new deal was only more of the same. What Salinas brought home from Paris was an agreement from banks to discount the debt, reduce interest rates, and agree to loan new funds—at the election of the bankers, not the Mexicans. In response, columnists in Mexico voiced second thoughts. “I have yet to see a single story saying what the debt deal really is—namely a lousy deal for Mexico, at best a stopgap measure,” Mexican scholar Jorge Castañeda complained. Financial analyst Christopher Whalen of the Wall Street Journal predicted, “Mexico’s total indebtedness, domestic as well as foreign, probably will be higher at year-end than it was at the beginning of 1989.” But most American newspapers applauded. The Dallas Morning News, for example, reported, “Now that Mexico has successfully renegotiated its foreign debt, other developing countries are hopeful they can reach amicable agreements with the banks.”

Because foreigners and important sectors of the Mexican business community all back his plans, Salinas is likely to make more headway in reforming Mexico’s internal economy. At that task, as in most of his other initiatives, however, Carlos Salinas is not an trailblazer but an understudy to De la Madrid. Although it will be years before Mexico establishes full participation, De la Madrid signed Mexico into the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs, a multinational pact aimed at reducing barriers to international commerce. De la Madrid also encouraged investment in maquiladoras, plants that produce solely for export. The number of maquilas in Mexico rose from 585 to 1,473 during De la Madrid’s six-year term, or sexenio, and more than 1,500 maquilas are in operation today. One happy result of the GATT and maquila expansion is that Mexican exports have risen; in 1989 Mexico will ship more nonpetroleum goods overseas than ever before.

Salinas has courted the Mexican business community, which has been formally excluded from political representation ever since the founding of the PRI. He sponsored legislation that for the first time in fifty years legalized the foreign ownership of companies in Mexico. So successfully has Salinas tailored his economic messages to business tastes that during last year’s presidential campaign, Manuel Clouthier, the presidential candidate of the Republican-esque Partido Acción National, repeatedly accused Salinas of stealing the PAN’s platform. PANista cynics jibed that government leaders were advocating perestroika.

But it is one thing to tout a program and another to implement it. During De la Madrid’s administration, the Mexican government sold or closed some 60 percent of the companies it owned, an accomplishment widely hailed in the American press. With the exception of the Aereonaves de Mexico, however, most of the enterprises trimmed were of tertiary importance; conservative economists in Mexico say that the companies generated only 3 percent of the income the government derived from business ventures. De la Madrid left to Salinas the task of selling Mexico’s most important operations, notably the government’s share of the national phone company. Salinas has not made big divestitures yet.

The vision revealed in the Salinas economic plan is one of a Mexico that competes with South Korea, Taiwan, and other oriental exporting nations. But while the plan may inspire business, it may also inspire labor unrest, just as perestroika has done in the Soviet Union. Mexico’s workers earn only a third as much as those in Singapore and Hong Kong. The PRI can’t afford to offend its labor base, which it depends upon for electoral victories.

Economic reform has thus far won few friends for Salinas and the PRI among ordinary people. Mexico must create a million jobs a year just to stay even with population growth, and it isn’t doing so. Unemployment is rising, not decreasing. During the De la Madrid administration, the purchasing power of the average Mexican shrank by 50 percent to a level below that of the seventies, and for the first time since the revolution, middle-class Mexicans began migrating to the north in numbers. They haven’t quit going yet.

The pinch that Mexico’s people feel comes largely from the elimination of federal subsidies on foodstuffs, one of Salinas’ accomplishments as budget minister. As a result, pork, red meat, and fish were practically removed from the working-class diet during the De la Madrid years, while even the price of tortillas and beans increased several times over. The subsidy eliminations, government officials admitted, were the result of pressure from the International Monetary Fund, which is supervising Mexico’s financial life. Obeisance to the IMF is popular in the press of creditor nations like ours, but it doesn’t play well at home.

Corruption

On January 10, after Mexican federal troops surrounded the home of Joaquín Hernández Galicia—better known as La Quina and the chief of Mexico’s petroleum workers union at Pemex, the national oil company—and, guns blazing, brought the union leader to jail, the Wall Street Journal‘s correspondent in Mexico declared that Salinas “quickly transformed his image from milquetoast to macho man.” The raid and its aftermath—La Quina is likely to linger in jail for the rest of the Salinas presidency—cast Salinas in the role of gangbuster, like a Bobby Kennedy facing down a Jimmy Hoffa.

Salinas, however, did not publicly confront La Quina, as Kennedy did Hoffa, and according to government spokesmen, he did not authorize La Quina’s arrest or know about it in advance. Such inaction hardly befits a hero. The official denials are barely credible, of course; they are best read as an attempt to mollify powerful unions. The official story is that the arrest proceeded from tips about arms-law violations—some two hundred Uzi machine guns allegedly were found in La Quina’s home—not from information about union mismanagement. The public-relations handling of La Quina’s arrest signals something less than a general campaign against recalcitrant labor leaders.

The actual motives for La Quina’s arrest may never be known, given the dearth of information available to the public and press in Mexico, where informed rumors tend to be more believable than official explanations. When the Mexico Journal (whose reporters have access to sometimes guarded information from wily Mexican newsmen at La Jornada, which owns the English-language newsweekly) put together what it knew with what it heard, it concluded, “For too many reasons, personal and political . . . Salinas’ choice of La Quina as the first victim of his modem politics reeks of revenge.” The Journal listed three slights that the union leader’s arrest avenged: First, La Quina was believed to have funded part of the presidential campaign of Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, Salinas’ principal opponent in the 1988 elections; second, even though he formally endorsed Salinas, La Quina informally made it known that he supported Cárdenas, and that helped Cárdenas carry the vote in most of Mexico’s refinery towns; and third (perhaps most important), La Quina supposedly was also behind a book published during the campaign describing how the PRI candidate shot and killed the family maid when he was a child. “Salinas,” the Journal said, “with the help of his current interior secretary . . . reportedly traced the book back to La Quina, and then waited for his chance to get even.”

The Journal‘s allegations about the interior minister’s detective work and La Quina’s sponsorship of a book are nearly impossible to verify; copies of telltale memos are not within the lawful reach of the Mexican press. But the homicide story is true. While Salinas was still a preschooler, on a visit to his family’s rural home he picked up a shotgun and unintentionally killed a maid. Salinas’ failure to confront La Quina lends credence to the charge that he ordered La Quina’s arrest.

After his arrest, La Quina signed a wide-ranging confession, as prisoners in Mexico usually do. But while reading it on a live television broadcast, the crafty union leader departed from its text to say that he had signed the confession only because he had been told that if he didn’t, he would never see his family again. When he tried to launch an impromptu defense, the broadcast was cut off.

It is sobering to recall that during his own crusade for “moral renovation,” President de la Madrid also played gangbuster: Former Pemex director Jorge Díaz Serrano spent the sexenio in prison. But Pemex did not become an honest or efficient company as a result, as the arrest of La Quina, its union chief, makes clear. In our own history, since Jimmy Hoffa was jailed, several high-ranking leaders of the Teamsters Union have also been investigated, indicted, and imprisoned. A similar succession is now taking place in the Mexican petroleum workers union.

The Press

On June 7, Freedom of the Press Day in Mexico, Carlos Salinas promised to clarify the mysteries surrounding the murder of Manuel Buendía, who had been Mexico’s leading newspaper columnist until his death in 1984. The president’s promise drew rapt attention from the Mexican press corps, which suspects that the Mexican government or the CIA or both had a hand in the killing. De la Madrid had promised to find the killer but had not turned up a trail, despite appointing special investigators to the case. If Salinas could succeed where his mentor had failed, Mexican newsmen reasoned, then perhaps his presidency really did herald a Mexican glasnost.

A few days after Salinas made his pledge, prosecutors named a killer. But solving the crime—if that is indeed what the Salinas government did—only heightened Mexican cynicism rather than establish Salinas’ credentials. The suspect, José Luis Ochoa Alonso, a former federal cop nicknamed El Chocorrol—loosely, “the Chocolate Roll”—matched descriptions of the killer as a “coastal type,” a man with Negroid characteristics. He was also identified by witnesses as the killer. But the solution lacked credibility for two reasons. First, El Chocorrol was dead—executed gangland-style by federal cops 41 days after Buendía died—and second, he had been accused in 1985 by the daily Ovaciones.

Without any explanation, a week later prosecutors named a different triggerman, Juan Rafael Moro, and the figure behind him as well. A white-skinned man, Moro was a former colleague of El Chocorrol’s. Moro’s principal, the prosecutors said, was José Antonio Zorrilla Pérez, a man whose life epitomizes the extent of corruption in Mexico and the nearly insurmountable difficulties confronting reformers like Salinas and De la Madrid.

Zorrilla began his public career in 1970 as the personal secretary to Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios, then a deputy minister in the Interior Ministry. Buendía visited the Interior Ministry often, and his contact with Zorrilla evolved into a deep friendship; Buendía dedicated his book on the CIA to Zorrilla. After serving a term as a federal deputy in the late seventies, Zorrilla became the head of the Federal Security Directorate, an agency that kept watch on dissidents. According to the charges against him, Zorrilla provided drug-runner Rafael Caro Quintero with the police credentials he used to penetrate roadblocks after the 1987 slaying of American Drug Enforcement Agency agent Enrique Camarena (Quintero has been charged with Camarena’s murder). Zorrilla is also accused of accepting several cars and more than $5 million from Quintero. The prosecution alleges that when Buendía threatened to publish information about Zorrilla’s drug connections, his old compadre ordered subordinates to kill him. Zorrilla has close ties not only to Gutiérrez Barrios, who is now Salinas’ interior minister, but also to Manuel Bartlett, the interior minister under De la Madrid and the education minister under Salinas. Courageous newspapers and opposition leaders are now asking how much Bartlett, Gutiérrez Barrios, and even De la Madrid knew about Zorrilla’s activities and when they knew about them.

The prosecution’s charges in the Buendía case are shocking because they expose federal protection of the drug trade. But allegations of official malfeasance are no longer a novelty in Mexico, and they do not necessarily compel change. Mexicans have grown accustomed to seeing one thug succeed another in office. Though the Buendía scandal has not touched Salinas personally, it speaks volumes about the administrative machinery at his disposal. In reforming Mexico, he will have to rely on corrupt incumbents to accomplish the task.

The Elections

If Carlos Salinas is a man on a horse, one of his chief problems is convincing his people that the horse he is riding isn’t stolen. His election in 1988 was the most fraudulent in Mexico since 1940, and—those who know will never tell—he may not actually have won. Official results gave him only decimal points more than 50 percent of the vote, and it is generally agreed that the runner-up, the nationalist and populist candidate Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, credited with 31 percent of the vote, was badly cheated in the tally. Nevertheless, a formidable opposition to Salinas and the PRI rose from the election, and its ascent has convinced optimists that a new day is at hand. Even melancholy philosopher and poet Octavio Paz, formerly identified with the opposition, declared faith in the future. “The secret and free vote of Mexicans,” he wrote, “in one day finished the one-party system.” Skeptics decided to wait and see if the prediction would be true. Meanwhile, Salinas renewed his vows to establish “a more transparent electoral process.”

On July 2 citizens in 4 of Mexico’s 31 states voted in legislative, congressional, or gubernatorial races. The focus of the press and opposition was on two states in which results were disputed on all sides: Baja California and Michoacán. In Baja, congresswoman Margarita Ortega Villa—handpicked by Salinas despite his promises of interparty glasnost—faced Ernesto Ruffo Appel, a shark-fin exporter and the former PANista mayor of Ensenada, who was nominated in open convention.

Ruffo and the PAN waged a thorough campaign against electoral fraud and found it, even before election day. For example, in one Tijuana district of some 8,000 voters—where 21,334 new electors had registered since last year’s presidential vote—party operatives exposed the registration of dozens of quintuplets and sextuplets: They had the same last name and the same birthdates; only their first names were different.

When the first tallies were announced, PRIista candidate Ortega conceded defeat, then did an about-face and claimed victory. But from Mexico City, Luis Donaldo Colosio, the president of the PRI’s national executive committee, called the election a PANista triumph. That caused Ortega’s supporters to fume that they had been betrayed. “Colosio’s announcement apparently headed off efforts by state PRI officials to usurp the election,” the Los Angeles Times explained.

The PRI had won by losing, the press said. “The defeat of the ruling PRI’s gubernatorial candidate may well be the opening of a new democracy in Mexico,” the Austin American-Statesman declared. The Dallas Morning News predicted that the Baja concession “may turn out to be the most significant act of his [Salinas’] already dramatic presidency.”

The Morning News also noted that in Michoacán “the PRI will likely continue to hold sway,” but it was in error: The PRI has not held sway in Michoacán since favorite son Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, a former governor, bolted from the party to head his populist opposition front. During the presidential elections last year, Michoacán provided Cárdenas with a victory so strong that two opposition senators were swept into office—for the first time in Mexico’s modern history. Michoacán was the banner of optimists in 1988, just as Baja California is today.

In this year’s Michoacán elections, however, the PRI claimed victory in twelve of the eighteen legislative seats on the ballot. Widespread, brutal, and inept fraud accounted for its triumph. In the La Piedad district, on July 3, with 74 percent of the ballots tallied, the opposition was credited with 1,230 votes; the following day, with 99 percent of the vote counted, the opposition total declined to 697. All the usual tricks—ballot stuffing, box theft, tally alteration, phantom polling places, padded lists, expulsion of poll watchers and of the local and international press—were documented during the election. During the scandal over Michoacán, some of the converts of 1988 recanted. Leftist intellectual Carlos Monsiváis, who in 1988 had declared, “This is a new country,” reported after seeing the Michoacán balloting that “we are now living through a native chapter of 1984.” Even the foreign press changed its tune. A week after having written that Ruffo’s victory “appears to usher in a new era of competitive politics,” New York Times correspondent Larry Rohter reported that the Michoacán results “have tempered some of the praise lavished on President Carlos Salinas de Gortari last week.” The Los Angeles Times agreed: “The credibility that [PRI] gained earlier this month after conceding its first governor’s race in sixty years is rapidly eroding.”

The Mexican press termed the election results “selective democracy.” In Baja California, a border state whose elections are closely watched by the foreign press and whose opposition looks with favor upon the Salinas economic program, the PRI had honored democracy. But in rural Michoacán, the PRI had flattened its strongest opponent by robbing victory from Cardenas’ followers inside his own house.

Mexico’s Jimmy Carter?

The elevation of Carlos Salinas to hero status by the American press is naively optimistic and premature—he has been in office for less than a year. The central problem of Mexican politics is not a national lack of educated leaders or well-crafted economic plans—Mexico has plenty of both. The central problem is lack of credibility. Only a great leader or a great movement can establish credibility. By tradition and law, the president of Mexico has vast appointive authority and nearly dictatorial powers over the Mexican congress. But patronage and legislation cannot transform the set of understandings behind the PRI’s monopoly: One says that perpetuating party rule is the only measure of public virtue, and the other, as old as the Spanish Conquest, says that public office exists for private gain. The task confronting Mexican reformers—winning a determined, broad-based national following to the ideals of good government—is not an official mandate. Thus far, the Mexican press, the opposition, and its candidates, not Carlos Salinas and the PRI, have made the biggest contribution toward that goal.

To reform his nation, Salinas must use as levers the kind of men the PRI has promoted, mainly men like La Quina, Manuel Bartlett, and Zorrilla. He can’t win with players like that. He can succeed only by forfeiting, and by forfeiting almost everything, including his party’s own power. For the remainder of his sexenio Carlos Salinas faces only one honorable course—accepting the same fate accorded to De la Madrid, who is considered the Jimmy Carter of Mexico. Salinas can’t become a hero, because heroes win.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Mexico