This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

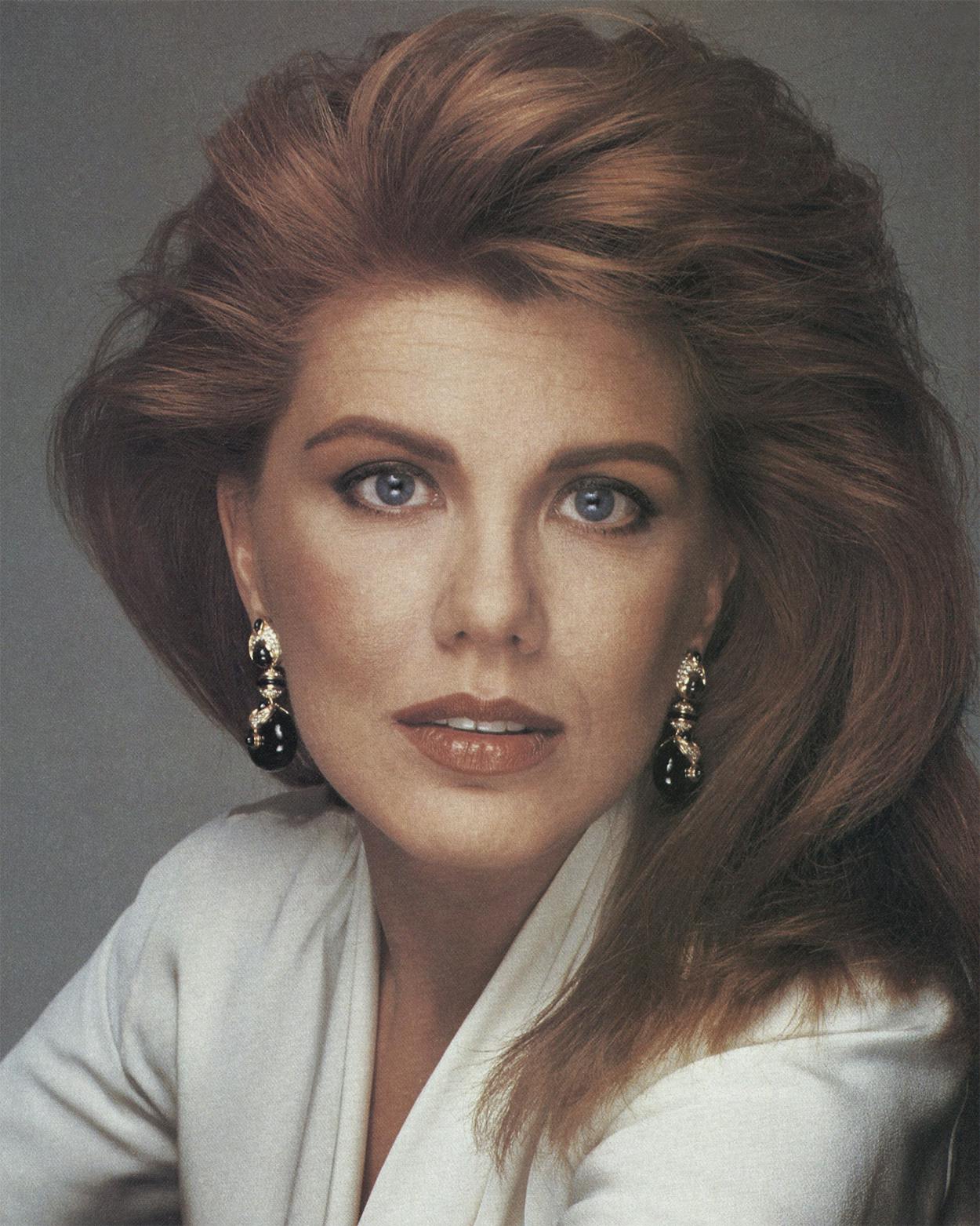

It has been a frantic morning in the Madison Avenue office of Georgette Mosbacher, 40, socialite, skin-care mogul, and wife of Houston oilman and Bush campaign finance chairman Robert Mosbacher, Sr. Operating on four hours of sleep (the couple jetted in from the first presidential debate at one o’clock in the morning), Mosbacher has been at the office since eight, completely in command, part Damon Runyon broad, part Cosmo girl. Mosbacher wears the uniform of the mega-well-to-do: Her coffee-colored Yves Saint Laurent knit embraces her bountiful curves, a gold clasp subdues her opulent red mane, the Bulgari knockoffs at her ears and throat telegraph a subliminal message of wealth and privilege. Still, marriage to one of Texas’ richest men and the social clout it brings have not changed the Indiana-born, twice-divorced Mosbacher as much as you would think. She can affect a lady-of-leisure pose for only a minute or two before lapsing back into unadulterated working girl. “I’m pressure-oriented,” she says, a firm resolve fixed in her fabled ultrablue eyes. “I move fast.”

She always has. Like many people who have engineered their own success, Georgette Mosbacher is more interested in the moral of her story than the details. Listening to her version of events, one has difficulty knowing whether she is being ingenuous or just plain cautious, shaping the past to fit a future that is still—and forever—in development. “I don’t know what you mean,” Mosbacher replies, when I ask whether the pressure of keeping up with New York’s Nouvelle Society queens Ivana Trump and Gayfryd Steinberg is ever overwhelming. Like fellow Hoosier Dan Quayle, Mosbacher has a tendency to take refuge in platitudes—“You can be anything you want to be” is her motto too. Unlike Quayle, Mosbacher has a story that validates the cliché: a poor girl from the Midwest moves to Hollywood, marries (Robert Muir, real estate developer), works (producing commercials for real estate firms), divorces (1977). She joins a cosmetic company, Fabergé, as an executive in a newly created film-production division. She moves to New York, marries (George Barrie, the chairman of Fabergé), works (as a Fabergé licensing executive), divorces (1982). Meets and marries (1985) Texas’ most eligible bachelor and nicest guy. Together they come up with about $35 million to buy one of the world’s most expensive skin-care lines (price of a jar of La Prairie eye cream: $65). Georgette becomes a familiar face in the social pages of the New York Times and W—although she does not manage to splash other Texas socialites like Lynn Wyatt and Anne Bass out of the social swim, she certainly claims her place beside them in the water. Now, with the Bush presidency, Mosbacher’s influence will extend to politics as well. “She’ll be a great asset at those tedious chicken à la king dinners,” one Houston social observer suggests. “The Republican party needs her.” There is an awesome economy to Mosbacher’s life, in which nothing is wasted and every part contributes to the whole—perfect for a woman who will help set the social agenda for the nineties. As with many women who have reached the top of the social ladder, it isn’t wealth, beauty, smarts, or wit that got Mosbacher there. It is determination, pure and simple. No peripheral vision.

From an office softened by billowy shades and surrounded by the spires of midtown Manhattan, Mosbacher fulfills her role as the chairman and CEO of La Prairie. With the assistance of a perpetually cowed secretary named Louise, she attacks the sort of tasks that squeeze the highest and best use from her business and social connections. Mosbacher dispatches baby gifts from Tiffany, contributes hefty charitable donations (“It’s worth it! These are good customers!”), pens timely thank-yous, and RSVPs to invitations (“That’s Empress Farah Diba,” she says helpfully). Frowning, Mosbacher fingers a lavender swatch, considering whether a polyester blend will be appropriate for La Prairie’s saleswomen. Impatient, she rules on an executive’s pitch to place La Prairie products in hotel rooms (“If we could get the suites—okay,” Mosbacher says. “If we get the tourists, it doesn’t do us any good”). Lunch comes from a pretzel vendor on the street (“I’m Pritikin, so I can only eat starch”); she rushes out to have her nails done at a nearby Korean nail salon when she cannot find a manicurist to come to the office at a price she can abide (“Five dollars for a manicure!” she says, exiting the salon exultant at the bargain, her drying fingers splayed into high hallelujahs. “In twenty minutes! Twenty minutes!”). Back at the office, she takes time out to speak briefly with her husband (“Hi, honey! How’s your day? Good. Good . . . Good . . . Gooo-ood. Goo-oo-ood! Good!”) before confronting a series of crises.

The first involves her dressmaker: Louise anxiously relates that Mrs. Farkas, the dressmaker, doesn’t know anything about Mosbacher’s Bob Mackie dress. Nor does she know anything about coming to the apartment for alterations. Mosbacher looks panicked, then puzzled. Then, tightly, she asks Louise where she found the number for Mrs. Farkas. The truth tumbles out: Louise has called not Mrs. Farkas the dressmaker but Mrs. Farkas the socialite—Kimberly Farkas, who is a lot more famous for wearing dresses than for fixing them. Georgette is not amused. If there were a sign blinking from Louise’s forehead at this moment, it would read “Days Are Numbered.”

Soon after, Mosbacher’s husband calls again to say that he cannot take her to Anne Bass’s dinner dance tomorrow night. Send the hostess flowers, the spurned Georgette insists. “Have one of your secretaries do it. Three dozen roses in a box. The really long-stemmed ones. In a box. The old-fashioned way. Yellow or white. One color. This,” she snaps, “is a major IOU. You’re going to wish you went to this party when I collect on this one.”

The calls keep coming. A testy Mosbacher picks up the receiver. She listens. She thaws. It is a reporter from the Washington Times who wants to know how the Bush White House would differ socially from the Reagan White House. Under her Empire desk, Mosbacher crosses her left leg over her right leg and then tucks her left ankle behind her right ankle. She purses her lips and raises her eyes to the ceiling, where trompe l’oeil clouds are always parting: “What is the Reagans’ style, and what is the Bushes’ style? The Bushes’ style is a less lavish style.” Mosbacher listens for a minute and then continues, her confidence growing. “I don’t think it’ll be less exciting. It will be more . . . intel-lec-tual. More intellectual. More national and international as opposed to show business, for instance. The Bushes will contribute more on an issue basis. On a social basis.” The reporter suggests that Robert Mosbacher might join the Bush administration and then asks another question. Georgette laughs a throaty you-can’t-be-serious laugh. “We would not be there playing a role in the social scene,” she says. “My office is in New York. My home is in Houston. I don’t see how we could handle another city.” Then Georgette Mosbacher hangs up—relieved and happy, wearing a satisfied look that says she could handle just about anything.

Anything You Want

Fresh from the dentist, Georgette Mosbacher sits surrounded by silk pillows on a sofa in the Houston townhouse she shares with her husband. She has dispensed with the designer clothes, expensive jewelry, and imposing makeup she wears for business—in a red housedress, embroidered slippers, and little makeup she almost looks like the carefree teenager she never really was. When I ask about the workings of her new bite plate—she’s been grinding her teeth at night—Mosbacher pops it into her mouth, grits her teeth, and stares at me, blinking.

“You have to set goals for yourself,” she tells me, a line that, banality notwithstanding, has served her well. “I wanted to be independent. Coming from a one-parent home, you don’t trust dependency. I don’t want to be in a position of depending on anyone.”

That was a notion shaped by family history: Georgette’s great-grandmother, widowed early, worked for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad until retirement age. Georgette’s grandmother divorced young and supported herself as a property manager for the rest of her life. Georgette’s mother ended up in similar straits in the small town of Highland, Indiana: Dorothy Bell was utterly devoted to George Paulsin, a charmer whose family owned and managed Highland’s bowling alley. Paulsin defied his family to marry his fiancée, whom they saw as lower class. The couple had four children; Georgette and George (there are two more daughters) were named after their father. “I loved my husband so much I would have named every child George if I could,” Dorothy Shepherd says today. But the family was thrown into chaos when Paulsin was killed by a drunk driver. When her mother went back to work, seven-year-old Georgette, who had been her father’s favorite, took over the child care. “The men in my family didn’t exist,” Mosbacher says. “There weren’t any men.”

Georgette always knew what she wanted. She spent her money astutely, preferring one angora sweater to three polyesters. Her powers of organization doubled as creative visualization: She converted a hosiery divider into a container for her costume jewelry with neatly labeled compartments for her faux pearls and diamonds. “She lives just like she did then, but today everything is real,” her mother recalls. Georgette was always pretty, but she didn’t bother with hometown boys. She was too busy improving herself. She stayed out of the sun, entered beauty contests, and worked, one summer driving twenty miles to a job as a Chicago switchboard operator during the day and returning home to Indiana in the evenings to sell sportswear at a department store. Always, Georgette ran the show. “She attracted girlfriends who needed her to help them,” her mother says. “She never had a problem. She was too busy solving her friends’ problems.” She graduated from Indiana University in 1969. After working for an ad agency in Detroit, she followed her brother to California, where he had become an actor (he is now an attorney).

Seen from today’s perspective, the next fifteen years assume a logic that may have been less obvious at the time. It was natural that Georgette’s film-production experience could get her a job with a cosmetics company pursuing that sort of expansion. It was natural, when that venture failed, that Georgette would find a new slot for herself with Fabergé. It was also natural that marriage to the head of Fabergé would be more glamorous than marriage to a Los Angeles developer. Those were the years Georgette added jet-setters like the Khashoggis to her roster of contacts. But the marriage to Barrie was a miserable match—the couple separated after a year and were divorced a year later. Georgette was on her own again. A mutual friend suggested she look up Robert Mosbacher—the scion of an old East Coast family, now the chairman of Mosbacher Energy—the next time her work took her to Houston.

The couple had their first date in the dining room of the Westin Galleria, where Georgette was staying. But before that meeting, the future Mrs. Mosbacher did her homework. She called an old friend, Susan Glesby, who was then living in Houston. Glesby, preparing for a big date of her own, was under the hair dryer and tried to put Georgette off. Her friend persisted. “I’ve just got one question,” Georgette pleaded.

“What is it?” Glesby finally asked.

“Robert Mosbacher,” Georgette said.

“He’s the second-most-eligible man in the world!” Glesby confided, agog.

“Who’s the first?” was Georgette’s next question, Prince Rainier having slipped her mind for the moment.

Georgette saw it as her mission to bring fun into Mosbacher’s life. He had enjoyed a long first marriage that ended tragically when his wife died at 44 of cancer. His second marriage, to prominent Houstonian Sandra Gerry, ended in divorce. “He married on the rebound,” Georgette says. “That was a disaster.” Georgette and Robert traveled to the South of France, to Los Angeles, to Africa on safari. “He’d always try to cancel,” Georgette recalls. “I’d have to intimidate him.”

When Robert Mosbacher was slow to meet Georgette’s marriage deadline, she employed, in the words of Glesby, “the oldest trick in the world: another man.” Georgette began dating a wealthy New Yorker. “Robert couldn’t stand it,” Glesby recalls. “So he claimed his treasure.” They married March 1, 1985.

It has taken Georgette somewhat longer to hook Houston—ironic, since she possesses in abundance the qualities that city seems to hold so dear. The social world is not known for its generosity; Georgette was flashy and unstoppable, and Houston’s reaction was familiar to many in the upper reaches of New York society. “I think the few people who look down their noses at her are women who are unnerved or jealous,” says syndicated gossip columnist Liz Smith diplomatically. “But the men are crazy about her.” In Houston Georgette suffered in the inevitable comparisons to Lynn Wyatt. They called her by her old New York nickname—“Jawsette.” People tsked over a Houston Post story that had Georgette trying on a $20,000 broadtail-lamb suit at Neiman’s and carping about her seat at a Bill Blass fashion show. They sniped when they learned she traveled with her makeup in a Ziploc bag (“I can see what’s inside, and every week or so I can throw it away and get a new, clean one,” she told the Chronicle). They weren’t impressed that she kept her social calendar on spread sheets either, or that she had had her eyebrows permanently darkened by a Gary, Indiana, tattoo artist (“I figured, who could do it better than a tattooist?” she told me). Perhaps Georgette hasn’t mastered the rules of etiquette, or perhaps she is just too economical in her use of them. Not that it matters—she’s won, after all.

Nowadays the Mosbachers retire to Houston every weekend, no matter where they are during the week. Georgette is easy to spot, driving around town in her beige Maserati, shouting orders to the New York office on the car phone.

The Personal Touch

Mosbacher’s pursuit of La Prairie mirrors her campaign for her husband. She says that her Fabergé experience left her hungry to own a cosmetic company. Applying La Prairie eye cream one night, she realized she held the answer in the palm of her hand. Soon after, Mosbacher launched her attack. She made a cold call to the company’s parent, American Cyanamid. “I didn’t get very far,” she says today, still grim at the memory.

But La Prairie was in need of rescue. It began life as an exclusive Swiss spa; skin-damaged people came from all over the world to receive pricey rejuvenating treatments from the placentas of black sheep raised on the premises (the $8,000-a-week spa now has only a tenuous link to the cosmetic company). In recent years, however, La Prairie has suffered an identity crisis. A small business (around sixty employees) in a sea of conglomerates (Chesebrough-Pond’s owns tony Erno Laszlo, for instance), it endured several changes in ownership. When La Prairie fell into the hands of a French concern called Sanofi, the new Mrs. Mosbacher used some Houston contacts to make her move. She called Sanofi every month for a year, offering to buy La Prairie. “I would pay whatever they wanted,” Mosbacher confesses. “I was prepared to commit the bulk of my resources to it.” With her husband’s backing and some shrewd New York advisers, Mosbacher beat out bigger guns, like Revlon, Avon, and Estée Lauder. Some people may question whether a former midlevel executive has the capability to run a corporation with $60 million in sales last year. Not Georgette. She hired Ted Thomas, a well-respected cosmetics-industry executive, to take care of the details as president while she carries out her own personal imperative—doling out beauty advice on a grand scale. There may be a lot at stake, but La Prairie is nothing less than her ticket to freedom. Here Georgette’s models are the so-called Working Rich, career women like Ivana Trump and designer Carolyne Roehm, who got big career boosts from their husbands’ millions. If there were once women who married so that they wouldn’t have to work, today those same women marry so they can work the way they want to. In endorsing La Prairie, Mosbacher’s pronunciation is strictly Sutton Place. “There is LITrally nothing like it on the market,” she tells me. “LITrally.”

On this October day, when the autumn sun bestows on Fifth Avenue its most promising light, Mosbacher prepares for a store tour. With account executive Edna Cuttler and an assistant, Diana Bozan, in tow, Mosbacher will call on La Prairie’s beauty advisers (read: saleswomen) at nearby Saks Fifth Avenue, Bergdorf Goodman, and Bonwit Teller. It is Mosbacher’s plan to build morale, something like Lee Iacocca paying unannounced visits to the best car salespeople in Detroit.

For her appearance, Georgette wears a silver Yves Saint Laurent power pantsuit. She wears a necklace of pearls the size of gum balls. Her earrings match her necklace, except for the added diamonds. Her hair is secured in a French twist. The final accessory: Mosbacher’s King Charles spaniel, the dog of choice among wealthy New Yorkers, introduced as Adam Mosbacher.

At lunch hour, Saks is packed to its finely paneled rafters. Mosbacher cases the store with her entourage trotting behind her and Adam trotting at her side. She zigs toward a jazz quartet promoting Yves Saint Laurent’s new perfume (“Too noisy for us,” Georgette declares) and zags through the aisles of cosmetic counters, turning up her nose at computerized makeup services. “Our customer wants more-personalized service,” she announces, “especially in this impersonal world.” She approaches the La Prairie counter under full sail but slows when she spots the beauty adviser with a customer. She briefly introduces herself and then passes on, out the door. While Georgette advances up the avenue expounding on her theories of personal service, Edna, a dark-haired, stylishly groomed woman, listens raptly, adoring as an acolyte. Adam jogs alongside, nails clicking on the pavement, sniffing at the noses of beggars’ Seeing Eye dogs. “My husband has two hundred employees,” Mosbacher begins, launching into a lecture. “He makes a point once a week to talk to all of them. He says look on their DESKS! On the WALLS! You’ll find something to talk about! There are ways of building personal relationships—no matter HOW BIG YOU ARE!” The group spins through revolving doors into the hushed environs of Bergdorf Goodman. In contrast with Saks, this cosmetics department is solemn and reverential—oval-shaped and carpeted, sort of like a museum for skin care. The counter contains a display for Skin Caviar, a $75 vitamin cream that comes with a silver spoon. It sits in a caviar dish, fanned by small paper napkins.

After greeting the counter manager—“Hi, Gail!”—Mosbacher gets an idea. “We’ll send Godiva chocolates to the telephone operators! That way they’ll put you right through to La Prairie!” Then it’s on to Bonwit’s and a final minilecture on the street. This one is about sunblock. “The tip is to put our sunblock on your hand—like hand cream!” Georgette insists, screaming a little over the traffic on Fifty-seventh Street. “Liver spots come from the sun. Brown spots come from the sun. And there’s NOTHINGYOUCANDOABOUTIT! Our compact says for eyes and lips—it SHOULD say for eyes, lips, and hands. My other tip,” Mosbacher says, pulling Adam away from a street light, “I’m never out on the beach without those cotton gloves. Even when you’re swimming. DON’T BE EMBARRASSED! I think it’s a great idea to bring gloves back! Put your hand cream on and your cutical cream and gloves!” Thoughtful, she slows her pace. The entourage leans in to catch her words. “Sleeping is not so easy in gloves,” Mosbacher declares. “But on the beach? You don’t get sand in your hands!”

Keeping Up Appearances

With the acquisition of La Prairie, Mosbacher’s social position can be used to advance her business and vice versa. She is not just a corporate head but a representative of a lifestyle. Every time other women see her, they will associate her with the product. They might come to believe that they are buying a bit of cachet with their night cream. In that way, Mosbacher’s visibility is profitable in more ways than one.

Tonight, for instance, we are riding in the Mosbacher limousine on the way to Mortimer’s Fête de Famille, an annual benefit. Georgette explains the importance of the event: “If you don’t show up, you don’t get a table for the rest of the year.” Since getting a table at the Upper East Side restaurant is an indisputable barometer of social status in New York, Georgette, who is headed—alone—for Anne Bass’s dinner dance later in the evening, has factored in 25 minutes for an appearance. The limousine glides to a halt. Georgette jumps out. Like an anxious Channel swimmer, she plunges into the crowd and starts stroking. She wears a black body-hugging number with a massive feather collar. “Is that removable?” a photographer asks, pointing to the spray of glistening black feathers. “No, it’s Chanel,” Georgette answers, shooting through a tented tunnel lit by photographer’s strobes, into the dimly lit party tent beyond.

It’s a W roll call at Mortimer’s, an impeccable assemblage of society and the people who make their living catering to it. In swift succession Georgette greets Bill Blass, Nancy Kissinger, designer Mary McFadden, Bergdorf Goodman president Dawn Mello, and Tiffany senior vice president John Loring. Georgette reminds everyone that she has bought La Prairie (“Six hundred Madison! Come and see me!”) and that Bush is going to win. “I’m a little overdressed,” she says breathlessly, “but I’m going to another party.” She meets Bob Miller, the sales manager for Victor Costa, who compliments her on a dress she wore to the opera the night before. “Oh, my God, he’s going to knock it off tomorrow morning,” she mutters, pushing ever onward. Fifteen minutes into the party, Mosbacher begins to work her way back through the crowd. Conspiratorially, she talks charity fundraising with a beaming CeCe Kieselstein-Cord. Reentering the tunnel of photographers, Mosbacher throws her arms around Kimberly Farkas, tonight a long, tall vision in a flowing white Mary McFadden. The combination of light and dark, grace and glitz, is too much for the photographers. An orgiastic clicking of shutters ensues.

Afterward, Georgette hustles toward her limousine. Before she flings herself into the back seat, she swerves to look back wistfully. “Kimberly just got here,” she frets. “And she’s going to Anne Bass’s!” Elapsed time: 25 minutes.

The Best Billboards in America

It is a social truism that women who photograph well are photographed often. On another fall day, for instance, an elderly society photographer has staked himself out on the street in front of the Fifth Avenue building where designer Arnold Scaasi is holding a premiere in his showroom. Spotting Georgette, he takes a step toward her and aims a large, cumbersome camera in her direction. Mosbacher, in the middle of hotly damning the Democrats’ behavior during the debate (“We didn’t clap until they started clapping. They broke the rules!”), stops herself. She draws herself up. She cocks her head slightly. Her eyes fill with a dazzling light. Her lips glisten. Her teeth gleam. The photographer clicks the shutter. “Thank you,” Georgette says gratefully. “Thank you,” the photographer gasps, stumbling back to his perch.

When Georgette was just a socialite, designers needed her more than she needed them. They were the ones who benefited most when she landed on the Chronicle’s best-dressed list or appeared on the Today show touting couture. Now, as a corporate head, she has all the more reason for dressing in a way that garners the right sort of style-setting publicity. The only problem, says Georgette, is that clothes have gotten so expensive (“Seven thousand dollars for Valentino ready-to-wear?” she asks in tough-girl tones. “For a sweater with no zipper so you have to pull it over your head?”) and she is just too busy to buy them. Mosbacher has had to cut back on her visits to designers’ shows—“They just send me the videotapes, and I pick from them,” she explains.

This afternoon, however, she finds herself in Scaasi’s small, sunny atelier to check out his new furs and holiday gowns (four-figure evening gowns are his specialty). The fashion press is represented by Vogue editor in chief Anna Wintour and New York Times fashion arbiters Bernadine Morris and Carrie Donovan. On one side of the room, Joan Rivers comforts her tiny Yorkshire terrier. Across the aisle sit the best billboards in America, members of New York’s Nouvelle Society, spectacularly married women who are young enough, rich enough, and prominent enough to capture the attention of the fashion press. They are Mrs. Donald Trump (Ivana), Mrs. Robert Trump (Blaine), Mrs. Saul Steinberg (Gayfryd), the former Mrs. Sid Bass (Anne), and, snuggling into her own front row folding chair, Mrs. Robert Mosbacher. Seeing them all seated together, perfectly coiffed, perfectly dressed, not a bad nose in the bunch, an outsider will experience a queasy sense of déja vù. They look like the most popular girls in high school.

The music comes up, the models waft down the aisle in lavish creations of chiffon, sequins, and fur. “That’s for going to the A&P,” Gayfryd Steinberg joshes to Georgette, studying a pink-satin ball gown with a matching reversible coat lined in mink. “It’s what I wear in the morning,” Georgette jokes. “I love ermine,” she says a few minutes later, her eyes locked on the snowy fur making its way down the runway. “But what can you do with an ermine coat?” she pines. “You can’t check it. You can’t leave it in the car!”

“You can wear it around the house,” suggests the frosted-haired, wide-eyed Kimberly Farkas, sitting to Georgette’s right.

Afterward, in the crush for the elevators, Ivana Trump, electrifying in a multicolored suit, with platinum hair and her eyebrows plucked into a state of permanent amazement, busses Georgette (“How eez zee companee?” she asks) before zooming on to catch her elevator. Other women congratulate Mosbacher on her new acquisition. “Did you get it?” “I got it!” “Are you having a great time?” “I’m having a great time!”

Riding down the elevator and locating her driver, Georgette seems exhilarated, almost satisfied with her accomplishments. It reminded me of a remark her sister, Lyn Gastevich, had made after attending a New York charity ball with Mosbacher. “All of a sudden I looked at her and she was on,” Gastevich said. “You could see it in her face that she was totally, happily content. She’d made her mark.”

As we ride up Park Avenue in her limousine, I am sure Mosbacher has made her mark, but I am not so sure she is content. Uncharacteristically subdued, Georgette dangles a leather-tipped khaki shoe from her foot and studies it critically.

“I was the only one there in flats,” she says finally.

“What’s wrong with that?” I ask.

“Nothing,” she says, peckish. “Thank goodness I don’t care what they think.”

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston