This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

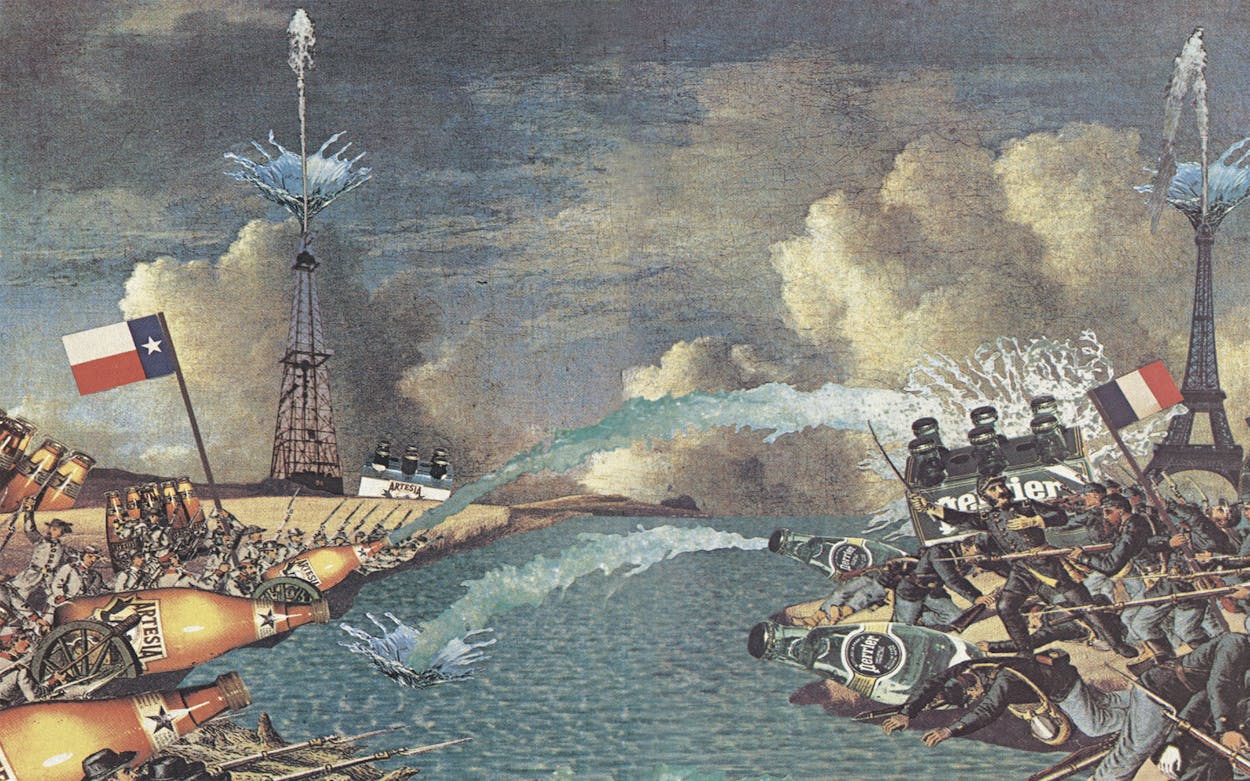

One afternoon in 1979, Rick Scoville, then a 34-year-old traveling glue salesman, was cooling his antelope-booted heels in the lobby of a San Antonio brewery when he read a newspaper story that changed his life. While waiting to make his glue pitch, Scoville read in the Wall Street Journal about French-owned Perrier Company’s total domination of the American bottled-water market. At that moment, Scoville made a silent vow that has become his water company’s business plan—he vowed to kick Perrier in the derriere.

That outburst of Texas machismo was the genesis of Artesia water, which now sells more bottled mineral water in Texas than Perrier or any other water company. Scoville, who has seen annual sales jump from $112,000 in 1980 to $3.5 million last year, runs his business according to one simple obsession: to defeat Perrier on Texas soil.

After he left the brewery that hot summer day, Scoville went right out and collected a sample of water from the Edwards Aquifer. In August he took the water and a bottle of Perrier to Texas Testing Laboratories and found that the aquifer water was higher in magnesium and lower in calcium than the French bubbly. Next, he added enough carbonation to give his product a good kick, and with fifteen bottles of the water, which he had christened “Artesia,” in hand, he went on a one-man crusade to convert Perrier sippers. Perrier’s bottles are cool, green, and European; Scoville chose to sell Artesia in small, brown bottles that look like tiny beer bottles. His first advertising campaign in 1980 was unabashedly nationalistic: He pitched Artesia as “Pure Texas Spirit” and ended each ad with “Au revoir, Perrier.”

The bureaucrats were scratching their heads, wondering how they’d gotten in the middle of a squabble over fancy water.

Scoville started his business at the beginning of the bottled-water boom. The boom is driven by a basic failure of the environmental movement: Unable to persuade the government to raise clean-water standards to their satisfaction, many environmentalists consumers are now taking refuge in bottled water. Scoville was correct in pitching his product to the mass market. The River Oaks, Highland Park, and Alamo Heights crowds aren’t the only ones who are willing to pay $1 for a product they can get free by turning on their tap; lots of suburbanites want assurance that their water is clean too. Since 1980, fears about the safety of municipal tap water have fueled a phenomenal 15 percent annual growth rate in the bottled-water business. In 1987 sales of bottled water increased at a faster percentage rate than sales of beer, wine, or soft drinks. Texans drink an average of 5.2 gallons of bottled water a year, making us the third-highest consuming state, behind—you guessed it—California and New York. If you thought the water shelf in your grocery store was getting crowded with new brands cropping up all the time, your perception was right on. In Texas 87 different state licenses have been issued to water companies vying for our dollar.

Not only can you lead people to water, but by peddling an image, you can also make them pay good money for a drink.

As in other parts of the country, French ownership dominates the bottled-water business in Texas. Perrier is by far the largest bottled-water company in the world, with sales of $1.2 billion a year. Both Ozarka and Oasis, the two biggest sellers of retail and wholesale water in Texas, are owned by Perrier. When Scoville first took aim at Perrier, he thought he was going up against one very large company. “Now they’ve bought up these other companies and completely control the market,” said Scoville. The bottled-water industry is big enough to have a statewide lobbying group called the Texas Bottled Water Association. Marcus Wren, the president of the TBWA and the owner of a small water company, agrees with Scoville that the French influence over rules and regulations is pervasive. “The French pretty much control everything,” Wren said. “Ten years ago, most of the bottled-water companies in Texas were family-owned. Now they’re being bought up by the big international companies.” For example, Anjou, a subsidiary of a French company that owns the Paris municipal water system, owns Hinckley and Schmitt, the U.S. company that recently purchased El Paso–based Five Springs Water.

Scoville found himself fighting the Franco-Texan war practically alone in December 1987, when the International Bottled Water Association and the TBWA teamed up to try to change the definition of mineral water in Texas in a way that would have prohibited Scoville from selling Artesia under the mineral water label. Under the definition that the water industry proposed to the health department, mineral water would have at least 500 parts per million of dissolved solids, otherwise known as minerals. As it happens, Perrier contains 505 parts per million and Artesia contains between 280 and 300 parts per million. “Essentially, Perrier was trying to use the regulatory process to drive us out of business,” Scoville said. The two other major independent Texas water companies, Ambrosia and Utopia, supported the proposed change. Representatives of both companies said Scoville was seeing a conspiracy where there was none.

Perrier’s attitude about Scoville’s accusation was understated, but Jane Lanzgin, a spokeswoman for Perrier, did imply that Scoville’s war was only in his mind. She indicated that the 500-parts-per-million rule had long been recognized by IBWA members as the standard for mineral waters and was the legal definition in fifteen states. William Deal, the executive vice president of the IBWA, was even more explicit when asked if the proposed definition was Perrier’s attempt to control the rules in Texas. “Poppycock!” he exclaimed. “Perrier has nothing to do with it.”

Scoville saw the invisible hand of Perrier everywhere. He asserted that the 500-parts-per-million definition was formulated while Ron Davis, the president of Perrier, was president of the IBWA. Moreover, Scoville said that of the twelve people who spoke in favor of the proposed change during public hearings last March, five had connections to Perrier and one was an officer in the TBWA.

Scoville charged ahead in opposition of the rule. “My definition of mineral water is any water that comes from a natural source and has at least one mineral in it. You can have five hundred parts per million of arsenic in your water and it wouldn’t be good for you,” said Scoville. He enlisted the help of hometown politicians. State Senator Cyndi Krier and San Antonio mayor Henry Cisneros both asked the Texas Department of Health to give Scoville a fair hearing. Krier was especially peeved. “What gall of a French company to come into Texas and try to manipulate the state’s regulations to run Texas companies out of business,” she said. The fight moved from the political to the personal; Krier went straight home from the grocery store and stocked her own refrigerator with Artesia water.

At the health department, the bureaucrats were scratching their heads, wondering how they had gotten into the middle of a squabble over fancy water. Dennis Baker, the director of the division of food and drugs, said with exasperation, “All we were trying to do was bring our regulations into compliance with those of other states.” Health department officials offered to write a grandfather clause that would have allowed Artesia to keep its valuable mineral-water label, but Scoville refused as a matter of pride. He made such a fuss that by last May, the health department had agreed to drop the 500-parts-per-million requirement. The new definition simply states that mineral water must come from a natural, nonmunicipal source and contain some minerals. “We won this round, but there will be others,” said Scoville, ever the underdog.

A measure of how big the bottled-water business has become is the variety of attempts to reform it. Remember the good old days? If you lived in San Antonio, you carried your own drinking water to Port Aransas because common sense told you San Antonio water tasted better. Well, life is not that simple anymore. Water is not always what it appears to be. There is no law that prevents a person from bottling tap water and selling it, and some people do just that. Fortunately, the new regulations, which become effective in January, require bottlers to list the source of their water. For instance, many vending machines outside grocery stores are connected to a source of tap water inside the store. As of January 1, the bottler will be required to list the source of such water as a municipal water supply.

A thorough reading of labels is shockingly educational. Most bottled water comes from a municipal water source. The advantage to buying water in a bottle is that the companies put the water through their own filtration systems and purify the water using chlorine. If you buy water in a bottle, it hasn’t traveled through city water pipes and, presumably, is purer fresh out of processing. However, it is still unsettling to read the label of Ozarka drinking water and find that it comes from the Fort Worth municipal water system or—egad!—from the Houston water system, depending on where you buy the bottle. The definition of “bottled drinking water” is very loose; “drinking” can mean almost anything, while “natural” means that the water can’t come from a municipal system. That’s the difference between Ozarka spring water and Ozarka drinking water; the spring water comes from a spring in Arkansas. Oasis drinking water is labeled “Mt. Carmel Water Supply,” which is Waco city water. On the other hand, Oasis spring water comes from a spring in Bell County, north of Austin. The source of Houston-based Ambrosia’s drinking water is a Harris County water well. Artesia is drawn from a well just north of downtown San Antonio. Utopia spring water is from a spring on a ranch near Utopia, in the Hill Country; Utopia drinking water comes from nearby water wells.

Texas water men say that if you want to know what is in a given bottle of water, buy your own test kit and check it out yourself. “There’s just no way to know for sure, unless you do your own test,” says Scoville, while acknowledging that it’s unlikely the average consumer will go to that extreme. The fundamental truth in the great Texas water fight is that not only can you lead people to water but also you can peddle an image and make them pay good money for a drink. Ambrosia is the official drink of the Houston Rockets. Scoville is proud that Artesia is served in the dining room of the New York investment firm of Shearson Lehman, as well as in the home of Vice President George Bush. Utopia water emphasizes its idyllic name and Hill Country environs. There is a reason for the emphasis on image: Unless you’re buying bottled water for the bubbles, for the convenience of having it brought to your home in a cooler, or for fear of a contaminated municipal source, water by any other name is still water.

Cool Clear Water

Ah, Utopia, Ozarka, Oasis, Artesia, Ambrosia. Taken together, the names of the state’s five leading water companies conjure up images of a perfect land, with rolling hills protected by a surrounding desert, where deep wells brim with the refreshment of the gods. But what do their products have in common besides those wonderfully evocative marketing labels?

Quite a lot. Whether from isolated ranch-country springs or urban water supplies, they all undergo state-approved filtrations that add an extra margin of purity without the chlorinated taste of city water. All except Ambrosia, whose source of spring water varies, offer middling amounts of minerals that are usually considered healthful and are chemically similar to San Antonio’s public water supply. Which brand one chooses is a matter of taste. What makes consumers want to pay for these products is the idea that bottled water may contain fewer pollutants than tap water.

Urban water emerges from the plant dosed with chlorine to kill bacteria. Then it flows by way of underground conduits, themselves a source of possible contamination, through miles of earth exposed to lawn fertilizers and pesticides. News of old, undiscovered dump sites and Superfund cleanups has made consumers anxious about the recommended eight glasses of water a day. That anxiety translates into profits for the bottled-water companies.

Chester Rosson

| Brands | Types | Source | Minerals | Size, Price | Processing |

| Ambrosia | Still spring water | Buck Springs, in Jasper County, bottled in Houston | TDS*: 17 milligrams per liter†, sodium-free, low in minerals | 1 gallon, 89ȼ–99ȼ; 2 1/2 gallons, $1.49–$1.69 | carbon filter, ozonation |

| Drinking water | Harris County (Coastal Sands Aquifer), bottled at source | TDS: 64 mg per liter, sodium-free, moderate in minerals | 1 gallon, 69ȼ; 2 1/2 gallons, $1.29 | deionization, carbon filter, ozonation | |

| Artesia | Drinking water | San Antonio (Edwards aquifer), bottled at source | TDS: 312 mg per liter, sodium-free, high in minerals | 1 gallon, 80ȼ–90ȼ; 2 1/2 gallons, $1.89–$2.29; 32 ounces, 85ȼ–95ȼ | sand filter, activated charcoal filter, 5-micron filter, ozonation |

| Carbonated well water | same | same | 7 ounces, $2.09–$2.49 per six pack; 32 ounces, 85ȼ–95ȼ | same, plus carbonation | |

| Oasis Spring | Still spring water | Tahuaya, in Bell County, bottled in Waco | TDS: 265 mg per liter†, sodium-free, high in minerals | 1 gallon, 89ȼ | carbon filter, reverse osmosis, ozonation |

| Drinking water | Mt. Carmel Water Supply of Waco | sodium-free, low to moderate in minerals | 1 gallon, 79ȼ | same | |

| Ozarka | Still spring water | Mena Springs, in Polk County, Arkansas, bottled in Houston | TDS: 150 parts per million, sodium-free, moderate in minerals | 1 gallon, 79ȼ | carbon filter, reverse osmosis, ozonation |

| Carbonated spring water | same | same | 32 ounces, 89ȼ | same, plus carbonation | |

| Drinking water | Tarrant County water supply | sodium-free, moderate in minerals | 32 ounces, 89ȼ | carbon filter, reverse osmosis, ozonation | |

| Utopia | Still spring water | Utopia Springs, near Utopia, bottled at source | TDS: 312 mg per liter†, sodium-free, high in minerals | 5 gallons, $5.75 to $6 (more in Houston), delivered; 1 gallon, 85ȼ–95ȼ | carbon filter, ultraviolet treatment, 5-micron filter, ozonation |

| Carbonated spring water | Utopia Springs, bottled in San Antonio | same | 1 liter, 79ȼ–89ȼ | same, plus carbonation | |

| Drinking water | company well near Utopia, bottled at source | same | 5 gallons, 50ȼ to 75ȼ less than spring, delivered | same as spring |

- More About:

- Business

- Water

- TM Classics

- San Antonio