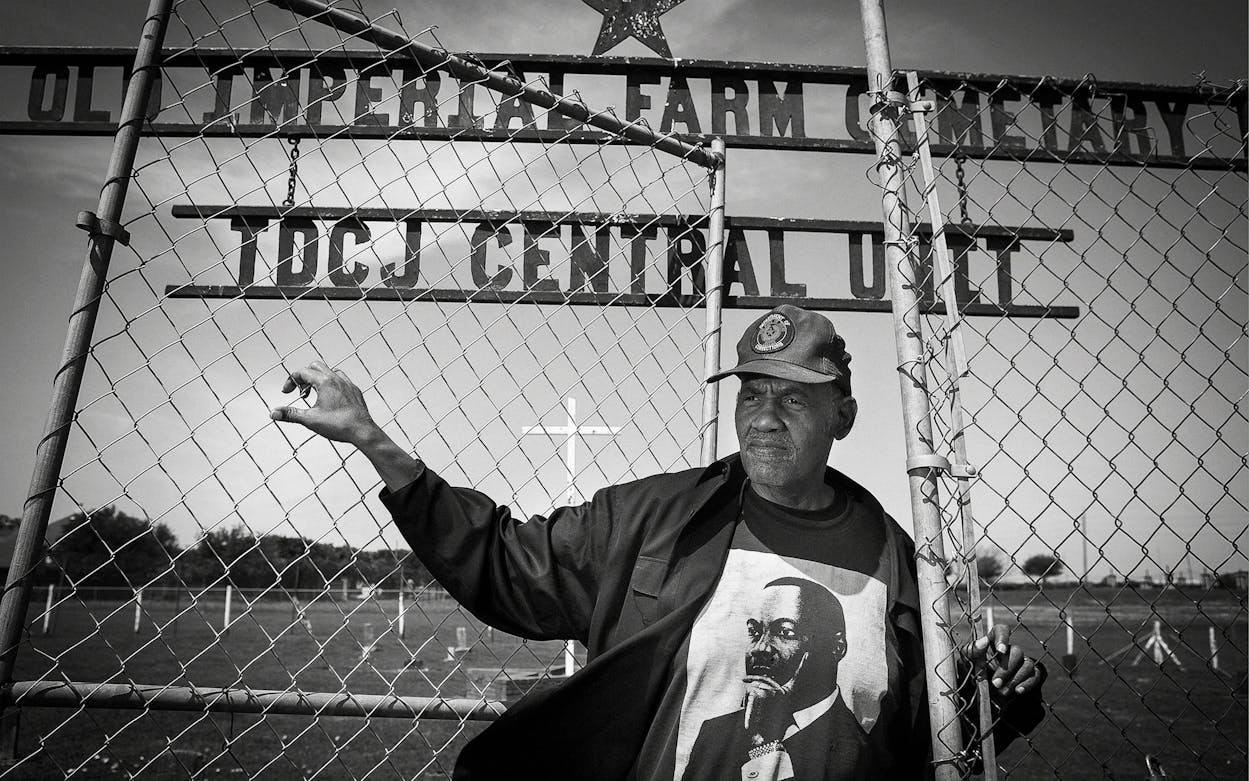

When I first met him in 2016, Reginald Moore was deeply frustrated. The retired longshoreman had spent much of the previous two decades trying—without much success—to bring attention to the brutal convict leasing system that flourished in Fort Bend County in the second half of the nineteenth century. Deprived of slave labor after the Civil War, plantation owners across the South started “leasing” laborers from state prisons, which had filled up with black men thanks to discriminatory new laws known as the Black Codes. The convict laborers worked in conditions often worse than those under slavery, but city officials Moore spoke to largely ignored the system’s existence.

Moore, who died of heart complications last week at the age of sixty, began researching convict leasing in Fort Bend County while working a brief stint in the eighties as a prison guard at the Jester State Prison Farm, outside Sugar Land. After retiring from his longshoreman job in the late nineties, he dedicated himself full-time to researching the sugar plantations that gave the future city its name. But when Moore requested that Sugar Land and Fort Bend County leaders erect a convict leasing memorial, he hit a brick wall. “There’s not a single facility, road, nor improvement that exists today in the city of Sugar Land that can be traced back to either the convict-lease program or slavery,” Sugar Land then–city manager Allen Bogard told me in 2016 to explain why the city was ignoring Moore.

That remained the city’s official position until 2018, when construction workers began building a new career center for the Fort Bend Independent School District—on land that used to be part of a state prison farm—and stumbled upon an unmarked mass grave. Archaeologists eventually uncovered the remains of 95 bodies, which they concluded were African American convict laborers who died in the early twentieth century.

Moore, who had repeatedly warned Fort Bend ISD that there were likely unmarked graves on the site, felt vindicated. “He tried offering information, he tried partnering with people,” recalled Houston activist Liz Peterson, who met Moore in 2018. “And time and again they turned him away. They figured he was at best ill-informed, and at worst a troublemaker. They didn’t want to deal with him. But when those bodies were uncovered, all of sudden they couldn’t ignore him any longer.”

The discovery of the so-called Sugar Land 95 made international news. After initially barring Moore from the cemetery shortly after the discovery, local officials eventually invited him to join a task force to advise them on how to proceed—only to mostly ignore his suggestions. “Reggie is a subject-matter expert on this topic, but often is marginalized because he doesn’t have the academic titles,” historic preservation advocate Sam Collins, another member of the Sugar Land 95 task force, recently told me. “He had done research and pointed all this stuff out, but nobody wanted to listen to him.”

A few did listen. Rice University history professors Caleb McDaniel and Lora Wildenthal offered Moore their support, and helped the Rice University library acquire Moore’s research archive in 2015. In April 2019 McDaniel organized a day-long convict leasing symposium at Rice featuring talks by some of the country’s leading historians; Moore gave the opening remarks.

In 2019, Moore also was invited to talk at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research by Hanna Kim, a student who had learned about his historical preservation efforts while taking a course titled “Culture, Conservation, and Design.” “He just blew everyone’s minds,” she recalled. Like countless others who came into contact with the tireless Moore, Kim soon came to share his passion for African American history; after winning a Soros Equality Fellowship, she moved to Houston and began collaborating on Moore’s research.

“Reggie was somebody who certainly knew how to call people out when they needed calling out,” said McDaniel, the Rice professor. “But he was also really skilled at calling people in, and building a community of allies—of friends, really. He insisted on our attention because what he was talking about deserved attention.”

One of Moore’s biggest fears, according to his friend Jay Jenkins, was that nobody would carry on his research and activism after he died. “He fought so many battles by himself, despite being told by so many people to stop bothering them,” said Jenkins, an attorney for the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition and a board member of the nonprofit Convict Leasing and Labor Project, which Moore founded. “You could tell it wore on him.”

But McDaniel, a Pulitzer Prize–winning historian of American slavery, said that Moore’s struggle to correct the historical record has laid the groundwork for more research into the state’s forgotten past. “Future historians will learn from Reggie’s archive not only about the history of convict leasing, but the history of the struggle to tell a more accurate picture of Texas history,” he said. “To me, the documents in the archive really highlight Reggie’s struggle to win that recognition.”

According to friends and colleagues, the stress of fighting seemingly never-ending political battles contributed to Moore’s premature death. Principled to a fault, Moore rejected anything he viewed as a half-measure of justice—such as reinterring the Sugar Land 95 at a different site, as Fort Bend ISD officials originally proposed, rather than keeping them in place and erecting a memorial. (The school district reinterred them in the same spot but has not built a memorial or placed any grave markers.) His uncompromising style created a long list of enemies, and could exasperate even his allies.

“There were definitely times when I didn’t agree with his tactics, or questioned a position he was calling for,” said Peterson, who also serves on the Convict Leasing and Labor Project board. “There were so many instances where my method might have been the more expedient tactic, but his was the tactic of real transformation.”

In the months before his death, Moore watched his decades of work start to bear fruit. The police killing of George Floyd, a fellow alumnus of Houston’s Jack Yates High School (though Moore and Floyd didn’t know each other) sparked a national reappraisal of race in American history. In June, Rice announced two new student internships and a travel grant dedicated to social justice research—all three named after Moore.

Perhaps most gratifying to Moore, according to friends, was the Texas Board of Education approving the state’s first-ever African American studies course as a high school elective. Moore testified before the board last November on behalf of adding the course. One of the class’s suggested lesson plans? A unit on convict leasing and the Sugar Land 95.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Sugar Land