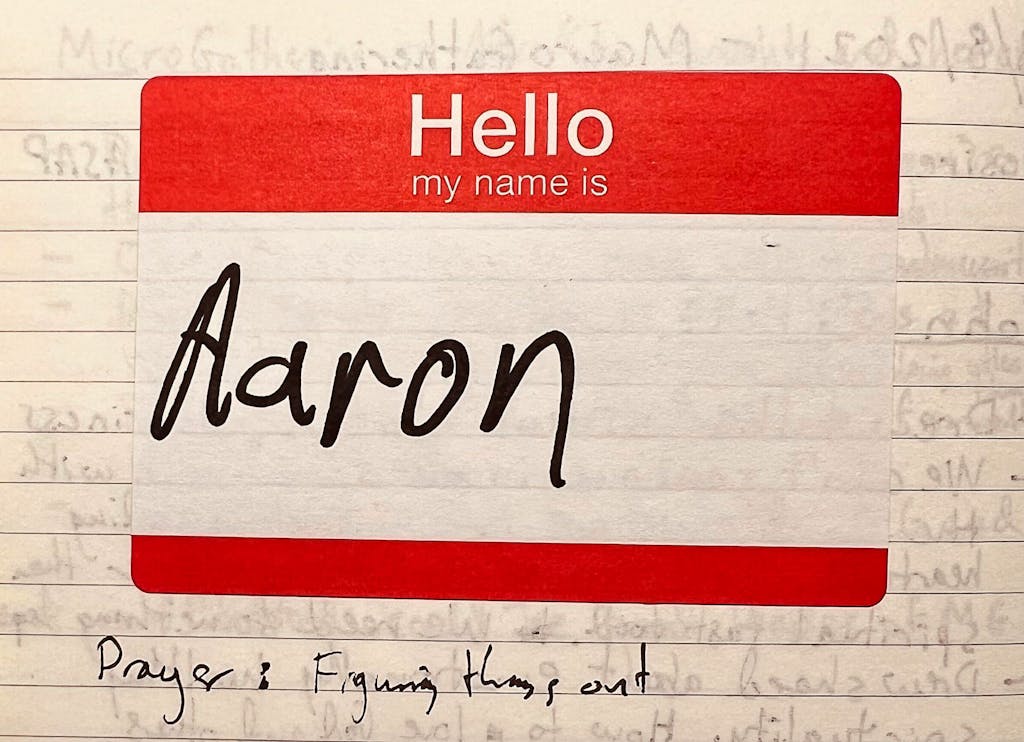

Stuart Rowe has found himself revisiting a name tag pasted to a page in his old journal: “Hello my name is: Aaron,” it says. It had belonged to Aaron Bushnell, the young Air Force service member who died last month after setting himself on fire in front of the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C., in an extreme act of protest against Israel’s actions in Gaza, which he called a “genocide” on social media prior to his death. In the journal, Rowe had written beneath the name tag: “Prayer: Figuring things out.”

The writing is a memento from the pair’s first meeting, in August 2021 at an Anglican church in San Antonio called the Gathering, where members were encouraged to swap name tags with someone they would pray for throughout the week. Rowe saw Bushnell sitting alone, he recalled, and introduced himself. Bushnell shared that it was the first time he had gone back to church since leaving the Community of Jesus, a rigid Christian group in Orleans, Massachusetts, in which he was raised. (In recent years, some of the Community’s former members have spoken out against the group, which has been characterized by some as a “cult,” alleging emotional abuse.) “He’s just trying to figure out things right now and has a lot of questions and wanted prayer during his transition,” Rowe wrote in his journal. They exchanged phone numbers that day, too.

Bushnell—who the Metropolitan Police Department says was 25 at the time of his death, though friends say he was 24—left Orleans in 2019 and joined up with the Air Force in 2020, relocating to San Antonio, where he was stationed at Lackland Air Force Base. The decision to join the military, friends say, was partly made out of a desire to move on from the Community. It wasn’t an easy transition. “He always said that one of the hardest things about making friends was that people didn’t understand the experience that he grew up in,” Rowe recalled. “It’s a big deal to leave the Community,” he added. “He was in a period of feeling grief over that loss.”

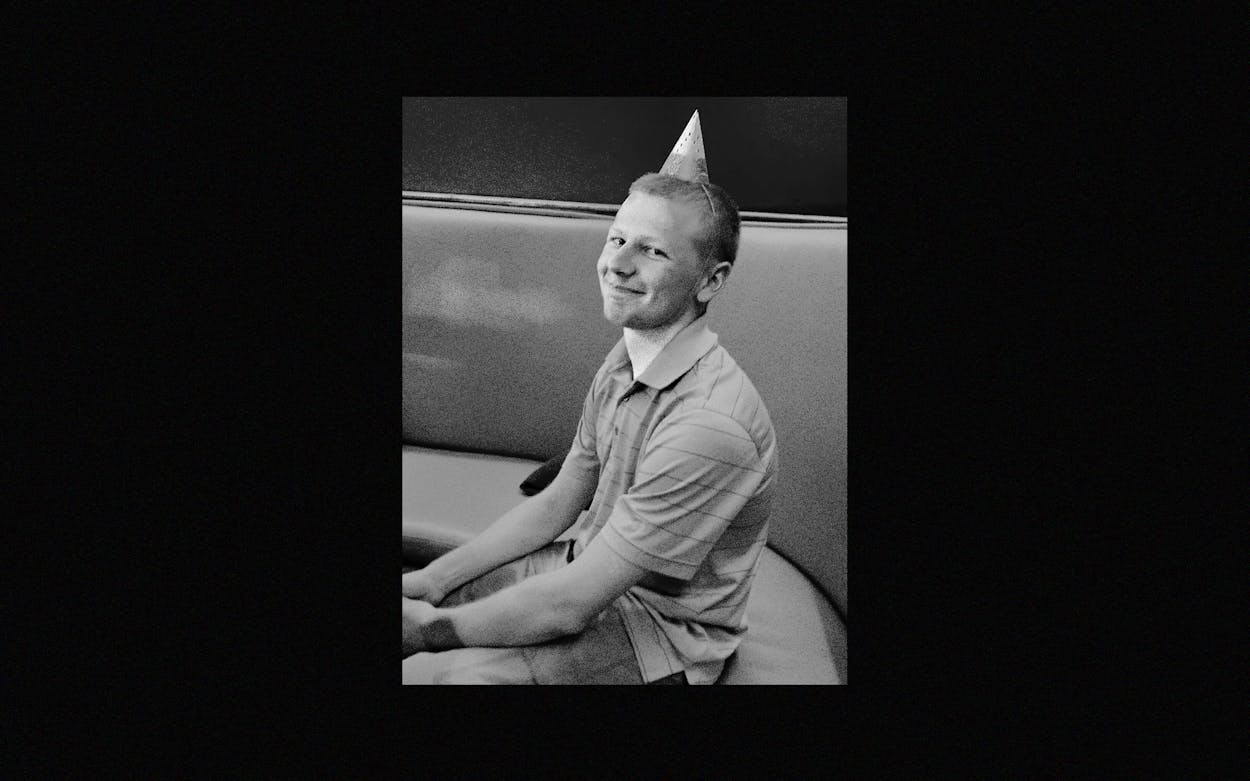

Rowe, 29, and his wife, Adriana Rios, 30, developed a close relationship with Bushnell and came to see him as a younger brother. They shared meals and saw one another at their Sunday gatherings. In many ways, the young man they grew to love was just your average twentysomething. He had two cats named Pumpkin and Sugar. He loved movies and, in particular, the Marvel multiverse. In other ways, he was disarmingly complex, not just sensitive and kind but also animated by a zeal for social justice and deeply frustrated by systemic inequalities. “Be discerning,” the couple told Bushnell when they saw him repeatedly go out of his way for others. He volunteered often, offering rides to unhoused folks at a moment’s notice or handing out clothes and other supplies through mutual aid groups. Bushnell was someone who “loved hard and loved quickly,” Rowe said. “If you were one of his people, you could count on him to show up,” Rios said.

One of those people was Terrence Bruff, thirty, who also met Bushnell at the Gathering. Bruff is autistic and has cerebral palsy, a group of neurological disorders affecting movement and muscle coordination. He doesn’t recall if he met Bushnell in 2021 or 2022, but he knows they instantly became friends. Bruff also has a photographic memory. “Every moment that I’ve had with Aaron, it’s just playing on a loop in my head,” he said.

The two played video games together at Bushnell’s dorm room in Lackland, Bushnell always offering up his only chair to Bruff, “because it hurt too badly for me to sit on a crate,” he said. They watched the Lord of the Rings trilogy together, the extended edition, meeting each weekend for three weeks to finish it. At Whataburger, they discussed the difficulties of modern dating and the shortcomings of dating apps.

Beyond their shared interests, Bushnell proved himself a caring and attentive friend. When Bruff’s dryer broke, Bushnell climbed over the machine to reattach the duct to the wall, a physical feat Bruff could not accomplish on his own. Bushnell regularly came by to help Bruff with his weighted blanket, which he used for his cerebral palsy. After Bruff told him about his fondness for exotic-flavored Oreos, Bushnell picked up Bruff from a treatment session toting four packages of lemon-flavored Oreos he’d purchased at Lackland’s commissary. “Most young guys are not selfless like that,” Bruff said.

Bushnell’s impulse to put others first might have stemmed from his upbringing within the Community of Jesus, a monastic community premised on collectivism. Its doctrine, titled “The Rule of Life,” describes the principles and procedures of living within the Community, which abides by the call to a “common life,” one in which all aspects of the Community are integrated. Married couples, children, and single adults join to “live as extended families within Community households.” The doctrine states, “Those living in households are prepared to move periodically from one home to another for the sake of strengthening communal life and meeting individual needs.” It also states: “We are to prefer others before ourselves and to pursue what makes for peace and common accord.”

Bushnell resisted the groupthink that accompanied the Community’s ideology of collectivism, said Rowe, especially as he began gravitating toward more left-leaning and anarchist political views. Nevertheless, Bushnell’s friends recalled that he struggled with his transition out of the Community. “It kind of goes against a lot of what you experience as an American,” Rowe said. “We are notoriously individualistic.”

That dissonance was sometimes a source of distress for Bushnell. He struggled to make sense of the ways life could be cruel or indifferent. When his car got broken into and vandalized, in October of 2021, a bereft Bushnell texted Rowe. “I find myself floundering for how to deal with it emotionally,” Bushnell wrote. “It feels like I’ve done everything I can to build a good life, and a bunch of senseless chaos is happening to me, and I can’t do anything about it.” He added, “Having people who do understand and are willing to do what they can do helps a lot.”

Bruff suspects Bushnell’s upbringing influenced him in other ways. “He was predisposed to extreme belief systems,” Bruff said, “because that’s what he grew up with—very regimented, very fundamental belief systems.” A former member of the Community told the Washington Post that it’s not uncommon for its members to join the military, since its rigid social structure is not unlike that of the religious group. “I always saw him striving to replace the feeling of community—lowercase c—he felt in the uppercase-c Community,” Rowe said. “He was trying to fill that hole in a way. And a lot of things couldn’t fill it.”

His friends say Bushnell struggled during his time at Lackland. He told Bruff that he didn’t have very many friends at work and that the shift hours adversely affected his sleep schedule; he struggled with insomnia. His role, which he did not specify to his friends, was very solitary. “He did not mince words talking about how much he disliked his day-to-day work in the Air Force,” Rowe said. (The Air Force could not be reached for an interview prior to publication.)

The other place where Bushnell sought a new sense of belonging, the Gathering, would ultimately fall short as well. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, church attendance waned, and in 2021 the school where the church held its meetings no longer wanted to host it, citing potential COVID contamination. At a church meeting that November, Bushnell made an impassioned plea to preserve the Gathering and, in particular, the small groups the church had formed as a pandemic response, where Bushnell had met his small cohort. He cited the positive impact it had made in his life. In December 2021, the church began sharing space with a sister church near the wealthy suburban neighborhood of Alamo Heights. The Gathering finally folded in March 2022, leaving many feeling stranded and isolated.

When Bushnell died, Rowe and Rios had since moved from San Antonio and hadn’t seen him in more than a year. But they had known him, at least for a time, intimately. They wondered what they had missed; they combed through their memories of their friend for clues. The last time Rowe spoke to Bushnell was around Thanksgiving. By that time, Rowe and Rios had relocated to Massachusetts and Bushnell had moved to Ohio to complete the SkillBridge Program, which helps military members transition into the civilian world. He had started a web-development job and sounded really positive about it, Rowe recalled.

In conversations she’d had with Bushnell, Rios said he often spoke with a sense of urgency about vertical systems of power. “He was always analyzing how power was moving.” He suggested that in order for any significant change to occur, existing systems of power had to be destroyed—“they had to be burned down,” she said. Rios would counter his argument with, “What happens next?”

Bruff last saw Bushnell in January, when he came back to San Antonio to visit. Over burgers, they discussed all matters except Gaza. “He gave me no indication that he was planning this,” Bruff said. Though Rios and Rowe also could not recall having any discussion with Bushnell about the war in Gaza, his opposition to the ongoing violence and calls for a free Palestine aligned with his beliefs, they said. In trying to reconcile the young man they knew with how he chose to die, Rowe and Rios speculate that he felt the weight of his uniform—that of the United States, a major stakeholder in the war—and the urgency of the cause.

“I will no longer be complicit in genocide,” said Bushnell, dressed in fatigues, before dousing himself in liquid and fumbling to ignite his pants with a lighter, while live streaming everything on Twitch. “Free Palestine!” he shouted, as flames engulfed him. At the end of his life, the only community present was the group of EMS workers who tried to put out the fire, and a security officer who trained his gun on Bushnell, as though he were a threat.

- More About:

- San Antonio