Richard Murray was still relatively new to the Houston political scene in 1972, when Harris County officials hired the young professor to help tabulate absentee election ballots. That year, as Murray recalls, “everybody was running for every office, and the paper ballots were about the size of a large American flag.” The count of mail ballots couldn’t legally start until polls opened on Election Day, and even with extra workers helping, the tabulation of many uncontested judicial races remained unfinished past midnight. So Murray cheated a bit: his final report to county officials on single-candidate races included some estimated final vote counts projected from incomplete data, which the judges later trumpeted as if they were official, historically high, down-ballot turnout totals.

“We just stopped. We were worn out,” Murray said, adding, “I assume the statute of limitations has expired.”

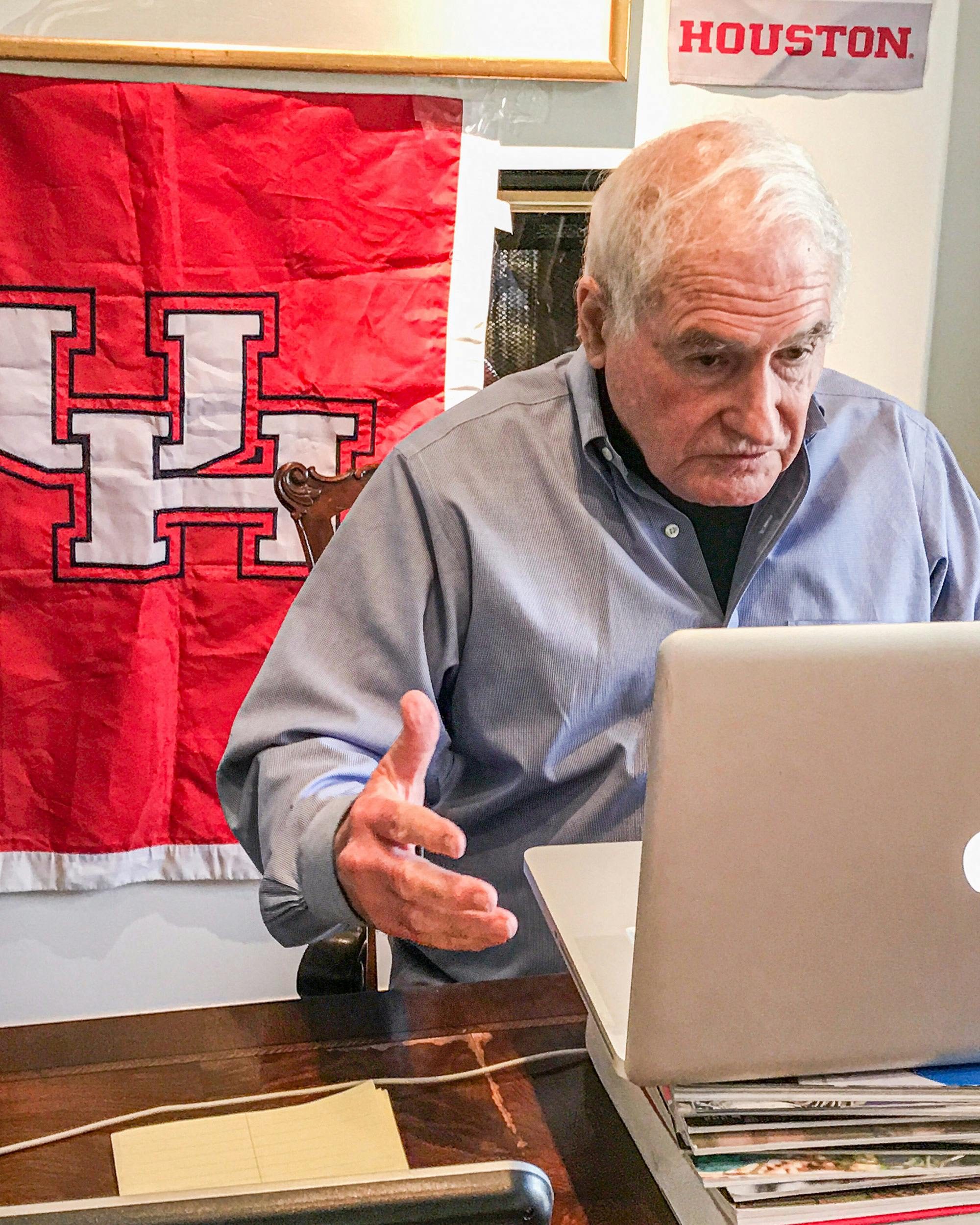

He would soon put the episode behind him as he burrowed into the city’s raw political culture through his many roles: teacher, on-air analyst for all three Houston network TV channels, pollster, raconteur, expert witness in redistricting and voting rights cases, and adviser to young politicians. When I learned that Murray had retired from teaching this month after 54 years on the University of Houston faculty, I imagined that the always-busy professor was easing into the comfortable life of an elder statesman, dispensing wisdom from on high while leaving workaday tasks to younger folks. But when I reached the eighty-year-old at his UH office, he was grading his final batch of student essays.

“I have 280 students who are demanding that they be graded. It’s rather unreasonable of them,” he said with a laugh, noting that he was one of a handful of faculty members who chose to work on campus this semester amid the coronavirus pandemic. Although he wrapped up his classroom work on December 4, Murray will continue doing research as a senior associate at the university’s Hobby School of Public Affairs.

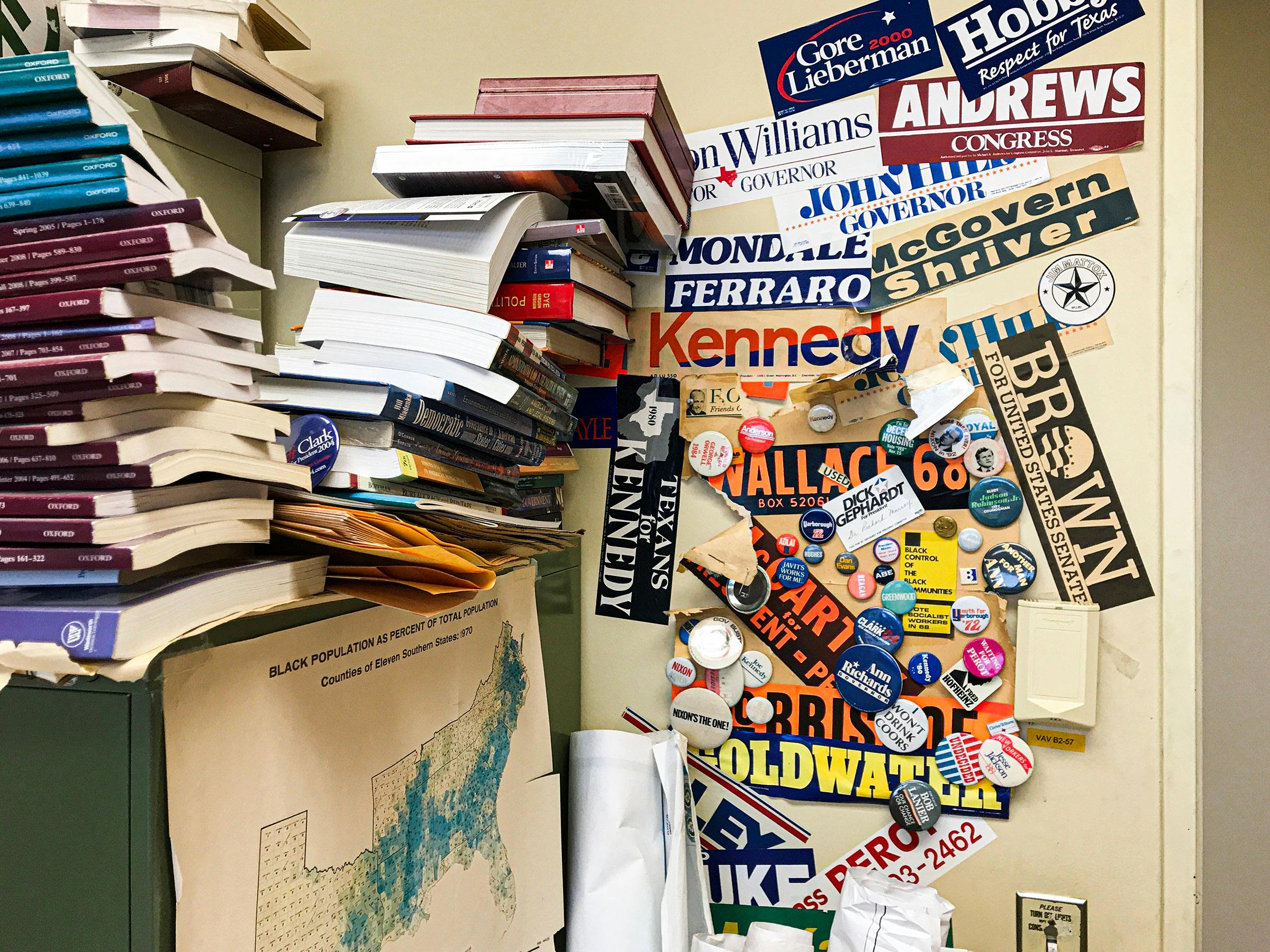

It’s doubtful that Murray, who grew up near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and once aspired to be a mechanical engineer, ever imagined he would become an institution in Houston politics and academia. He had only a passing acquaintance with the city when he arrived in September 1966 to teach political science at UH. As he became acquainted with the political landscape of his new home amid the social turmoil of the late 1960s, Murray realized that rather than political theory, he was drawn to “behavioral” politics focused on real-life elections. He developed a reputation as an expert analyst and pollster, and any reporter who covered politics soon possessed a well-thumbed Rolodex card bearing Murray’s name and number. Political aspirants of both parties flocked to him for free advice. At one time or another, anyone who consumed news about Houston or Texas politics likely heard or read Murray’s insights.

“Dick could look at a precinct or a council district or a congressional district, and just look at the numbers and tell you what was going to happen,” said Robert Stein, a Rice University political science professor who has collaborated with Murray on research and polling projects. “He was uncanny in predicting turnout.”

His polling and punditry sometimes led to backlash. Then-governor Bill Clements “went berserk,” Murray said, when the professor released a poll showing Democrat Mark White unexpectedly leading the Republican incumbent by five or six percentage points in their 1982 campaign. White ended up winning by seven. In a Republican primary debate four years later, Clements mocked an opponent for employing the same pollster who had incorrectly predicted he would win the earlier campaign. (Clements won the 1986 primary and defeated White to regain the governorship.)

During his 1981 campaign for a third term as Houston’s mayor, Jim McConn was similarly annoyed when Murray remarked: “I don’t think this guy can win; that’s why everyone in town is running against him.” Murray, once again, was correct: McConn failed to make the runoff in a four-candidate race, and Kathy Whitmire was elected to the first of five terms. But in retrospect, Murray says now, “the McConn people were perhaps justifiably unhappy. Usually I try to stick more to numbers, factual patterns.”

Murray’s most profound influence, though, might have come through a less public role: his work in the classroom. He estimates that fifteen to twenty of his students became elected officials over the years—judges, state legislators, local politicians. Among them was John Whitmire, the dean of the Texas Senate, who has traced the start of his political career to a 1971 visit to Murray’s UH office. Whitmire recalls that when he arrived to ask for an extension on a class paper, he found the professor studying a redistricting map. Whitmire and Murray agreed that the demographics of the student’s neighborhood were a good fit for him, and he ran successfully as a Democrat for a new district in the state House of Representatives, which he won, serving until he was elected to the Senate a decade later.

Carol Alvarado, who has served as a Houston councilwoman, a state representative, and now a state senator, studied with Murray in the nineties. “I was that student who would stay after class and ask him questions,” said Alvarado, a Democrat whose district covers a large swath of eastern Houston and Harris County. Later, when she sought elective office, Alvarado’s relationship with Murray continued: “If you were interested in politics, you had to go talk to Dr. Murray. He knows census tracts, he knows data, he knows trends. He has such a good historical perspective of everything.”

Some of those classroom relationships grew into formal political advising. Murray volunteered in the late 1960s to help a Black state legislative candidate whose wife was one of his students. The candidate lost, but the experience acquainted Murray with leaders of that era such as Barbara Jordan, the first Black Texan elected to the Texas Senate after reconstruction, and city councilman Judson Robinson Jr. These relationships led to volunteer work for other Black candidates, and ultimately to his role as an expert witness in a 1970 redistricting lawsuit.

Murray shared his insights in less formal settings as well. One evening around thirty years ago, he bumped into two young reporters at a Montrose area restaurant-bar, and they got to talking about politics over drinks. This encounter evolved into “the roundtable,” a weekly gathering which, at its height, attracted city council members, legislators, aides, consultants, reporters, and occasionally the mayor. The roundtable gatherings became a fixture of Houston political life and “a stop on the road to Bagby Street [where city hall is located] if you wanted to be mayor,” said a charter member of the group, Doug Miller, a longtime KHOU television reporter who now is director of news and media relations at Rice University. “A lot of the politicos dropped by to get free advice from Dick Murray. He would share his wisdom with anyone, Republican or Democrat, who cared to ask.”

The roundtable stopped meeting a few years ago; as its members’ ages have increased, their late-night drinking prowess has subsided. “We sort of petered out,” said Murray. Now as he settles into something like retirement, the professor has grown reflective. During the pandemic this year, he’s coped with isolation by talking politics with his son Keir, a Democratic consultant, and other guests in Zoom sessions posted online. I asked Murray whether he believes the institutions he’s spent his life studying are imperiled by the disinformation, polarization, and other toxins coursing through American politics and culture in the closing weeks of Donald Trump’s presidency. “The guardrails are pretty badly damaged now,” he said. “People have lost trust in government.”

He paused. “It’s a dangerous time, and we ain’t out of it yet, by any means.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston