This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There’s a saying in politics that a year can be a lifetime, so quickly do fortunes rise and fall. The Texas Democratic party has discovered to its sorrow that half a year will do. Just six months ago everything seemed to be going the Democrats’ way. Republican governor Bill Clements was stigmatized by revelations of his leading role in the SMU football scandal and cover-up. By insisting on deep cuts in education as the way to balance the state budget, he had led his party into a legislative battle that it was doomed to lose. The Democrats had the education issue and the candidates, Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby and San Antonio mayor Henry Cisneros. Even Republicans were conceding that 1990, the year of the next gubernatorial election, looked like a Democratic year.

Then came the twin shocks of late summer. First Hobby, then Cisneros withdrew from electoral politics. Now the Democrats face the likelihood that their nominee will be attorney general Jim Mattox, who barely defeated a neophyte Republican in 1986 and who, as the Republicans will no doubt remind us, might well be in jail today but for a vote of twelve of his peers.

Some strange malaise has overtaken the Democratic party. On the national level its three best candidates for president—senators Sam Nunn and Bill Bradley and Governor Mario Cuomo—have declined to run, leaving the field to a group that has become known as the Seven Dwarfs. Now the same fate has befallen the party in Texas. The Democrats seem bent on acting out Yeats’s terrible prophecy for the twentieth century: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/are full of passionate intensity.”

To insiders Hobby’s departure from the race was not entirely a surprise. In his fifteen-year career as the leader of the Senate, he has shown an affinity for government, not politics. He is an effective leader of those who are inclined to listen (as when he persuaded a Democratic governor to support a tax bill in 1986) but an ineffective negotiator with those who are not (as when he was unable to persuade a Republican governor to support a tax bill in 1987). In retrospect, it is clear that Hobby’s declaration to run for governor in 1990 was a mistake. He could no longer do what he does best—posture himself above politics, as one who cares only about what is best for Texas. Instead he made himself a target. Republican strategists like party chairman George Strake, still smarting from a stinging defeat by Hobby in the 1982 election, saw the budget fight as a chance to bring Hobby down. They lost the substantive battle—in the end, Hobby’s position prevailed—but they won the political war. Given a taste of the vitriol that awaited him, Hobby chose not to partake.

Cisneros’ withdrawal is harder to understand. At issue is not his reason—family illness—but his timing and the way he reached his decision. The burden of having an infant son with an incurable heart problem (see “The Time of His Life,” TM, September 1987) must make run-of-the-mill politics seem insignificant by comparison. But Cisneros is no run-of-the-mill politician. He would have been a solid favorite to win in 1990, and it does not take much imagination to envision Texas’ first Hispanic governor as the Democratic nominee for president in 1996 or 2000. That is a lot of future to reject. No one would have questioned Cisneros had he said, as is undoubtedly the case, that he has higher priorities at the moment than deciding his political plans. But why did he find it necessary, three years in advance, to declare himself out of races (a challenge of Republican senator Phil Gramm was also a possibility) he had never been in?

There has never been any question about Cisneros’ intelligence and integrity. There has, however, been occasional doubt about his impulsiveness and his commitment to politics, dating back to the time in 1977 when he threatened to resign from the San Antonio City Council because he had not been named mayor pro tem. When Cisneros made his recent announcement, without talking to either his political adviser, Austin consultant George Shipley, or his mentor and uncle, Ruben Munguia, the doubt resurfaced: Did he really prefer a safer course, such as seeking a Cabinet appointment?

Perhaps the one element missing from Cisneros as a politician is the love of a good fight. To succeed in the exacting world of politics for the long haul, a politician needs more than the motivation to do good. The nature of politics, sad to say, is that good is hard to do. Between the rare opportunities a Lyndon Johnson, a Jim Mattox, a Bill Clements, draws sustenance and succor from putting his enemies to the sword. Henry Cisneros and Bill Hobby do not. They may be better people as a result, but the Democratic party is the worse for it.

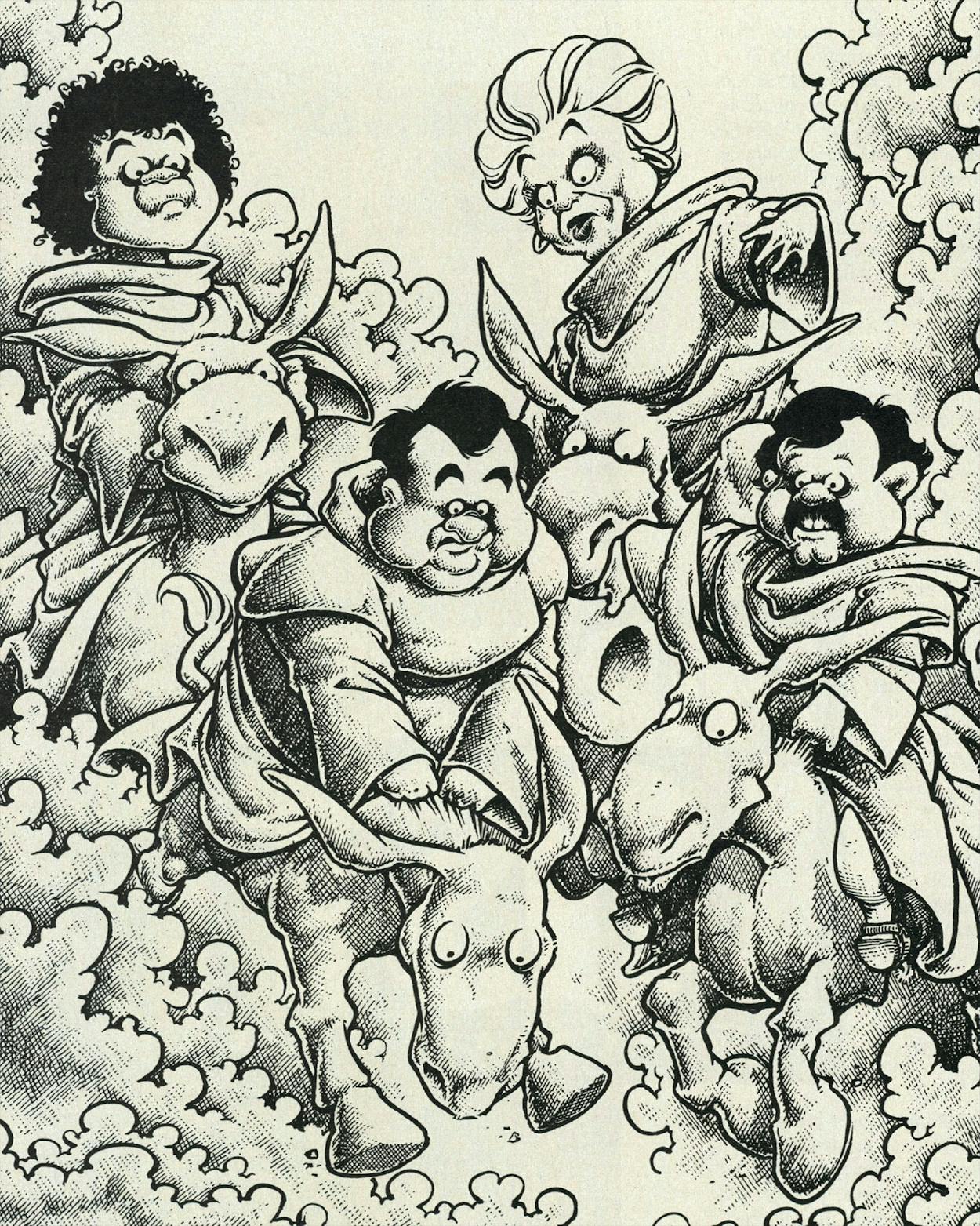

Now the Democrats are left with the Texas version of the Seven Dwarfs: the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. A political apocalypse may indeed occur if some combination of Mattox, land commissioner Garry Mauro, agriculture commissioner Jim Hightower, and Treasurer Ann Richards constitutes the Democratic ticket for senator, governor, and lieutenant governor in 1990. All come from the liberal wing of the party, which hasn’t produced a winner in any of those races since 1964. All carry other baggage. Richards is a recovered alcoholic. Mauro has been under fire for his financial wheeling and dealing. At a time when family issues play a major role in politics, Mattox, Hightower, and Richards are conspicuously single (Richards is divorced). State comptroller Bob Bullock, a recent entrant into the lieutenant governor’s race, isn’t identified with the liberals, but he too is a recovered alcoholic. Meanwhile, the resignations of Democrats from the Railroad Commission and the Supreme Court have given Bill Clements the chance to groom GOP candidates; he has already resurrected Kent Hance’s career by naming him to the Railroad Commission.

More will be at stake in 1990 than a few high offices: Control of Texas politics is in the balance. During the following year, 1991, the Legislature must reapportion itself. A Republican governor can veto the Democratic majority’s plans and, under the Texas constitution, automatically shift the task to a body known as the Legislative Redistricting Board. Its five members are the lieutenant governor, Speaker of the House, attorney general, comptroller, and land commissioner. At least three of those positions will be vacant in 1990. If the Democratic ticket collapses, a GOP-dominated board will draw legislative districts to its liking. The prize is within the Republicans’ sight at last; the House and Senate could be theirs by 1993. Meanwhile, the Democrats can take solace in remembering that a year can be a lifetime in politics.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Austin