Tom Craddick has served in the Texas House of Representatives since before the first man walked on the moon. At 54 years in office and counting, he is the longest-serving state lawmaker in the United States. For one out of every three days that the House has been in session since statehood, Craddick has been a member. He represents Midland, the pumping heart of the Permian Basin—the largest oil basin in the country and one of the largest in the world. So it should come as no surprise that for most of the past half century, Craddick has sat on the Energy Resources Committee, which oversees the misleadingly named Railroad Commission of Texas, the powerful body that has nothing to do with railroads but instead regulates the state’s oil and gas industry. From 2003 to 2009, he served as a feared and formidable House Speaker, the first Republican to hold that position since Reconstruction.

Craddick’s official Texas Legislature web page describes him as a “successful businessman” who owns an investment company. What it doesn’t mention has been an open secret in Austin for decades: Craddick not only regulates the oil industry, but he also makes a lot of money from it—in ways that apparently are legal under Texas law but pose substantial and obvious conflicts of interest. No one knew just how much money he was making, or how widespread his holdings were, until Texas Monthly recently examined royalty data from 41 county tax offices from Laredo to Lubbock and San Angelo to Van Horn. These offices record who owns even a tiny fraction of the royalties for the state’s oil-producing wells.

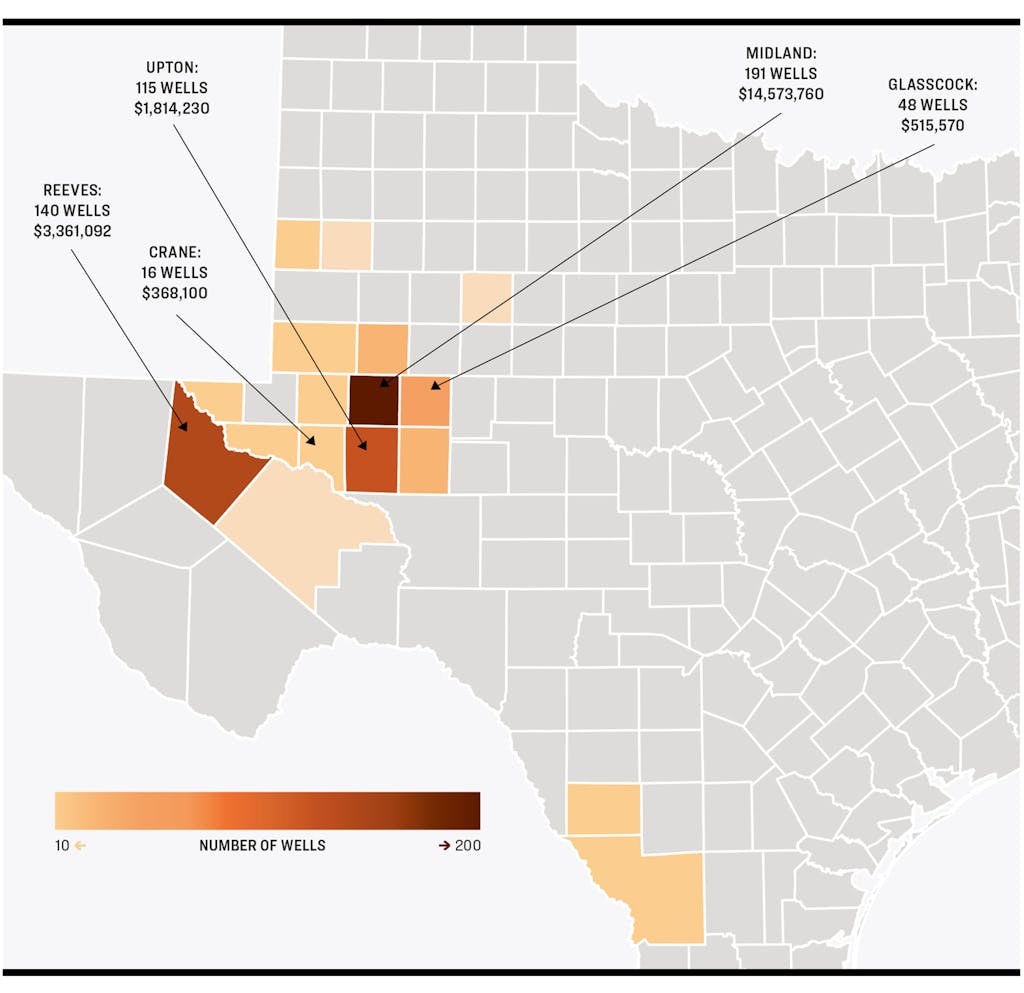

Craddick holds slivers of approximately six hundred oil and gas leases and receives a percentage of the value of the fossil fuels produced from them. Much of his family is involved, and some of his holdings are co-owned by his daughter, Christi Craddick. That’s notable because she has been an elected member of the Railroad Commission since 2012 and currently serves as its chairman, which makes her the state’s top oil and gas regulator.

The family business mixes oil and politics, and business is good. Last year the Craddicks’ mineral interests in hundreds of wells across seventeen counties entitled them to profits from a river of oil that, based on prevailing prices, earned them about $10 million. What’s more, the appraised value of the family’s mineral holdings—based on anticipated future royalty payments—totaled more than $20 million. That doesn’t include royalties from wells that have yet to be drilled, which may be substantial.

Having a powerful state lawmaker and an even more powerful state regulator profiting from oil deals makes good business sense for the fossil fuel industry. The sector “wields a lot of power and influence across the state, and I think it probably does whatever it can do to make sure it holds on to that,” said Dan Gattis, a Republican House member from 2003 to 2011 who was one of Tom Craddick’s lieutenants. “The oil and gas industry is going to work hard to protect itself. I’ve watched it happen.”

For the Craddicks to get rich off oil interests while regulating those same interests is ethically troubling, said Luke Warford, a Democrat who ran unsuccessfully for railroad commissioner last year. “One of the roles of a public servant is to ensure public confidence in our institutions and our government,” he said. “They are failing at this.”

The Craddicks don’t drill or operate wells. Instead, Tom Craddick has been a consummate dealmaker, bringing together oil companies, large and small, to buy and sell leases. For his trouble, he typically takes what’s called an “overriding royalty interest.” This entitles him to revenue from the oil and gas output. For Craddick, it’s a sweet deal. He doesn’t have to put up any investment capital. He doesn’t share in the costs of drilling. He just sits back and counts the royalties as they flow into his bank account.

What does Craddick do to earn his cut? Drawing up a mineral lease and assigning an overriding royalty is not a time-consuming job. But what matters in these deals are the hours spent schmoozing at the Petroleum Club of Midland and making phone calls to figure out who is selling and who is buying. Brokers such as Craddick rely on their contacts and reputation. “Unlike other industries that have adapted to the new age of technology, oil and gas deals are very old-school,” said Austin Kuenstler, president of the Permian Basin Landmen’s Association. “It is all about handshake relationships.”

Neither Tom nor Christi Craddick agreed to be interviewed for this article. Instead, they issued a statement to Texas Monthly through Bill Miller, the cofounder of HillCo Partners, an Austin lobbying and public relations firm. “Their experience and knowledge about the industry and our state’s natural resources is one of the reasons why voters have consistently reelected Tom and Christi to public office,” the statement read. The Craddicks, Miller added, cast votes to ensure that Texas has a robust oil and gas industry “that promotes energy independence and security and supports hundreds of thousands of jobs.”

While the Craddicks’ ownership stakes tend to look relatively small—sometimes just a fraction of a percentage point—the payouts can be quite large. Consider the Alkaline Earth leases, about twenty minutes southeast of Midland. Four wells were drilled on the leases in 2020, and they began producing oil the following year. Midland County assessed the value of the leases in 2022 at $83.4 million. The operator and largest owner was CrownQuest Operating, the twelfth-biggest oil producer in Texas.

CrownQuest’s CEO is Tim Dunn, one of the most powerful figures in the state, who wields unparalleled influence over Texas’s elected officials. Dunn is a major Republican donor who has pushed for restrictions on the development of renewable energy, as well as on voting, reproductive rights, and transgender students’ participation in sports. The second-largest stakeholder of the Alkaline Earth leases was Tom Craddick, whose fractional interest was appraised at $2.64 million.

You’d never know how lucrative Craddick’s stake in these wells was if you looked at the personal financial statements he provides to the state. That’s because disclosure guidelines in Texas are as flimsy as a wet paper towel. Last year Craddick reported earning royalties worth more than $46,580 from CrownQuest—the highest figure that the Texas Ethics Commission asks lawmakers to disclose. Craddick’s public filing doesn’t reveal that his interest in the CrownQuest wells entitled him to payments for more than 20,000 barrels of oil last year, worth an estimated $1.9 million. Because his stake was an overriding interest, he didn’t have to pay any of the substantial costs of drilling or fracking. It was all profit.

Craddick holds some of his oil and gas interests under his name and others through a limited partnership called Craddick Partners. According to records filed with the state, Tom and his wife, Nadine, as well as his daughter are general partners and part owners of the company. Again, he had to disclose only that he earned more than $46,580 in income from Craddick Partners. Texas Monthly added up the output from wells in which the company had a stake in 2022 and found that Craddick Partners’ interest entitled it to more than 38,000 barrels, worth $3.5 million.

Born in Beloit, Wisconsin, Tom Craddick came of age in Midland, where he was an Eagle Scout. He served in student government in high school and again as an undergraduate at Texas Tech. Craddick recently told the National Conference of State Legislatures that at the beginning of his political career he wanted to be a U.S. congressman, and he figured that serving in Austin would be a good stepping stone to Washington, D.C. His ambitions weren’t exclusively political, though. Before his first election, he told a friend that he wanted to make enough money to leave his children a million dollars. At the time, he wasn’t married and didn’t have children.

Craddick was 25 in 1968 when he was elected to the Texas House. The job clearly suited him better than he had expected; he never ran for Congress or for any higher state office. In the early seventies, the Texas Legislature paid its members $6,480 per year (including a $12 per diem) in the odd-numbered years when the lawmakers were in session; that’s equivalent to $48,709 in today. To earn more, Craddick became a “mud” salesman—an unglamorous job selling fluid used in drilling oil wells.

Craddick was successful in politics and eventually in the oil business as well. When he joined the Legislature, Texas was ruled by Democrats. In 2002 his years of recruiting candidates and helping Republicans raise funds paid off when Craddick helped the party win control of the state House for the first time in more than a century. Craddick, a pro-business, low-tax conservative, was elected Speaker. He was “the most powerful Speaker ever,” Paul Burka, Texas Monthly’s longtime politics writer, wrote in 2009, in large part because Craddick would recruit and finance an opponent to unseat almost anyone, Democrat or Republican, who crossed him. Eventually, his heavy-handed tactics sparked a backlash; in 2009 Craddick was deposed and replaced as Speaker by Joe Straus, a moderate Republican with a more conciliatory leadership style.

As Craddick gathered political power over the decades, he also had been amassing a growing stake in the state’s oil fields. In 1976 the lawmaker and his wife created the Craddick Children’s Trust for their two young kids. The family began dissolving the trust in 2013, long after the children became adults, with the assets transferred to a company called Quarry, controlled by his daughter, Christi, and son, Tom Jr. Like Craddick Partners, Quarry holds pieces of wells across several counties.

Tom Craddick was a wheeler-dealer, a broker who connected buyers and sellers of leases for drilling. He told Texas Monthly in 2005 that his fee for brokering deals was a stake of between 1.5 percent and 3 percent. “The art of making the deal is the thing for me,” he said.

After he lost the speakership, in 2009, Craddick’s power in the Legislature declined precipitously. But he was given a plum first-floor office, along with assignments to the Energy Resources and State Affairs committees. “He retained a base of influence because of his deep roots in both policy and politics in the energy sector,” said James Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas. Still, his new role marked a step down from the preceding three decades, when he’d served not only as speaker but also as chairman of the formidable Ways and Means Committee and the Natural Resources Committee.

After her graduation from the University of Texas School of Law, Christi Craddick went to work as an oil and gas lobbyist; her father’s political action committee reportedly paid her $1 million over seventeen years for consulting. Not long after he was replaced as Speaker, he helped her launch her political career. In 2011 she announced a run for an open seat on the Railroad Commission. “Growing up in the Permian Basin, I have a unique understanding of the oil and gas industry,” she said. “It is the economic engine that drives the Texas economy.”

Christi Craddick had never previously run for elected office. In the Republican primary, she faced state representative Warren Chisum, of Pampa. From the beginning of her campaign through the end of the primary, she raised nearly $2.4 million. Her largest donor, by far, was her father, who contributed more than $600,000. More than $1 million came from other donors with oil and gas interests. Craddick outraised Chisum by a margin of more than two to one and defeated him in a runoff before dispatching her Democratic opponent in the general election. Since taking office, she has been an unabashed supporter of the oil and gas industry, even in cases where its interests seemed at odds with those of most Texans. About 1.5 percent of the state’s workforce has jobs in oil and gas extraction and production, and another 1.1 percent work on pipelines and in petrochemical manufacturing and refining, while all Texas residents are affected by the prices of petroleum products as well as by the industry’s impact on air and water resources. During the extended freeze of 2021, for instance, the failure of natural gas companies to weatherize their facilities—a legal requirement in most states but not at the time in Texas—contributed heavily to the multiday blackouts suffered across the state. Meanwhile, the injection deep into the ground of salty water used in fracking has “almost certainly” triggered numerous West Texas earthquakes in the past couple of years.

With Tom Craddick serving as a member of the energy committee in the Texas House and Christi Craddick as one of the elected officials who run the state agency that regulates oil, the family has exerted enormous influence over Texas energy policy. And with Christi Craddick as a commissioner, staffers of the agency were put in the awkward position of being assigned to regulate wells in which the father of their boss—and sometimes by the boss herself—held an interest.

Take, for example, the Alkaline Earth wells in which Tom Craddick holds a 3.1 percent interest. They’ve required a lot of attention from Railroad Commission employees. In 2020, before the wells were drilled, the agency’s staff cited issues with CrownQuest’s lease. The commission issued six so-called problem letters, an unusually large number. They flagged errors with the paperwork and layout of the leases that needed correcting before CrownQuest could begin drilling. CrownQuest complied and drilled four wells in October 2020. Between January and June of 2021, the Midland company completed them by fracking layers of petroleum-bearing rock, installing cement and pipes to protect shallow aquifers, and connecting the well pad to pipelines. By the end of the year, all four wells were producing oil.

A few months later, in March 2022, Railroad Commission staff issued six more problem letters. It is not clear what prompted this new examination, but the staff identified more issues. One major snafu was that one well extended into, and was taking oil from, land tracts that weren’t on the paperwork, according to the letters. CrownQuest filed amended leases and drilling permits to fix the problems. This was no small matter. Reallocating the wells would determine which mineral rights owners would be paid for the oil produced.

The Alkaline Earth wells were very productive, pumping more than 700,000 barrels in 2022, according to Railroad Commission records. The oil was worth about $64 million, and Tom Craddick’s overriding royalty interest amounted to about $1.9 million.

How was Craddick in a position to collect such a windfall? The answer dates to a deal he arranged involving Exxon, based just north of Houston, while he was accumulating seniority and political power as a member of the Texas House. In 1988 Craddick was involved in a sale of several leases from Exxon to Parker & Parsley Petroleum. (Parker & Parsley later became part of Pioneer Natural Resources, one of the largest Permian Basin oil producers.) Exxon transferred the leases to Craddick, who turned around and, later the same day, conveyed them to Parker & Parsley. Parker & Parsley then provided Craddick and a partner with an overriding royalty interest. Documents filed with Midland County indicate that he and his partner together received a 25 percent overriding royalty, significantly more than Craddick’s typical fee of 1.5 to 3 percent.

It is unclear why he received such an unusually large interest, or why Exxon and Parker & Parsley didn’t simply deal directly with each other, rather than involve an expensive middleman. Austin Kuenstler said some brokers are simply paid with a transaction fee. Among those who receive an interest in the lease, Kuenstler said, he has seen brokers take as little as half a percent to as much as 5 percent for their dealmaking but never anything above 10 percent. Bill Miller, speaking on behalf of the Craddick family, said Tom Craddick drives a hard bargain. “He squeezes everything and he takes advantage of business opportunities,” Miller said. “That is who he is. That is just the man.”

Asked about the unusually large royalty interest, a spokesman for Pioneer replied that the company “does not comment on the details of our private leasing transactions, and we are unable to address one managed by a predecessor company 35 years ago.” Exxon officials did not reply to requests for an interview.

Craddick was well known to be friendly to Exxon. In 1989 he authored a controversial measure in the Texas House urging Congress to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for oil exploration—a move that would benefit Exxon and one that the company was lobbying for. Craddick filed the bill just days after the Exxon Valdez oil tanker ran aground and spilled millions of gallons of crude into Alaska’s Prince William Sound. “You’re going to have spills,” Craddick said at the time. “It’s just something that happened.”

The Alkaline Earth leases were particularly lucrative for Craddick. But this was just one of many such deals he’s done over the years.

In 2022 Tom Craddick held slices of 274 leases in the counties whose tax records we reviewed—all of the major oil-producing counties in West and South Texas—while Craddick Partners held pieces of 327 leases. Quarry, still owned by his son and daughter, held pieces of 55 leases. Altogether, the taxable value of the Craddick family’s leases amounted to more than $20 million.

Issues with these leases sometimes come before the Railroad Commission. In some instances, at least, Christi Craddick has not recused herself—and it’s not clear whether she’s required to, thanks to the ambiguous conflict of interest rules under which the Railroad Commission operates. One such instance occurred in 2020. Quarry owns a slice of the Ringo 9 lease in Reagan County, about 46 miles southeast of Midland, that was operated by Parsley Energy. In 2018 Parsley sought, and received, permission from the Railroad Commission staff to flare off natural gas when needed, over a two-year period. This allowed the company to produce valuable crude oil without waiting for sufficient gas pipelines and processing facilities to be built for the purpose of preventing the air pollution that comes with flaring. In 2020 Parsley asked for another two-year extension. This time, the matter required a vote by the commissioners. Christi Craddick voted, along with the two other commissioners, to allow Parsley to flare off gas.

“The public is counting on elected officials to make good decisions about our collective future and not their own personal wealth,” said Virginia Palacios, executive director of Commission Shift, a nonprofit watchdog group based in Laredo that advocates for reform of Texas’s oil and gas oversight. Had the Ringo 9 well been in Oklahoma, the rules would have been different. There, state regulators are required to exempt themselves from voting on any matters that involve their mineral interests.

Even in Texas, members of the Public Utility Commission must divest from all investments in industries they regulate, and they can’t derive any money from regulated utilities. But there is no similar requirement for those who sit on the Railroad Commission. One major effort to reduce conflicts and raise the ethical bar was undertaken in 2013, when the Texas Sunset Commission recommended limiting campaign contributions from oil and gas companies to railroad commissioners. The matter died in the Legislature.

Commission Shift has documented multiple instances where Christi Craddick voted on matters in which she had a financial interest. In 2020 she intervened in a dispute between Williams Companies, an Oklahoma-based pipeline enterprise, and CNOOC, a China-based energy firm, over the rates Williams charged to move natural gas through its South Texas pipeline. Craddick proposed a motion to address the dispute, which the commissioners approved in a unanimous vote. At the time, she owned shares in both companies.

During the next year’s legislative session, Tom Craddick proposed a law that could preserve for generations the flow of oil money to his family. The bill was written to benefit those who hold overriding royalties, favoring their interests over those of other parties to complex oil and gas deals, by addressing something called a “washout.”

What’s that? Let’s say Big Oil Company leases drilling rights from a ranching family called the Smiths, taking 75 percent of future oil revenues and leaving the rest for the landowners. Big Oil Company doesn’t do much with the lease, and some years later the company agrees to sell the lease to a small operator called Permian Oil, in a deal orchestrated by Joe Broker. For his work, Joe gets a 3 percent overriding royalty, leaving 72 percent for Permian Oil and a 25 percent royalty interest for the Smith family. A small well is drilled, and everyone makes a little money.

Then, years later, Permian Oil decides to terminate the existing lease and then signs a new lease with the Smith family (or more likely, the children and grandchildren of the Smiths who made the original deal). Terminating the old lease means that Joe’s overriding royalty is “washed out” and legally disappears.

In Craddick’s bill, if a washout is done in “bad faith,” or expressly to erase the overriding royalty, Joe Broker can sue for damages and attorneys’ fees. When Craddick filed the bill in 2021, recent court cases had weakened the legal protections of override holders. His legislation was designed to help them, said Bill Keffer, a professor of practice at Texas Tech’s law school and a two-term Republican state representative from Dallas County. “There’s such a concentration of people who have overrides in Midland, irritated that they were losing streams of revenue, that they decided to do something about it,” he said.

Appearing at a hearing of the judiciary committee in 2021, Tom Craddick explained his bill. “Mr. Chairman, if you do this for a living, you’ve earned your override,” he said. “It’s wrong.” Craddick didn’t mention that nearly two-thirds of his family’s mineral holdings are in overriding royalty interests. He didn’t disclose that the bill would give the Craddicks legal leverage if anyone tried to cut off their steady stream of payments. He also did not point out that he and his family were earning millions a year from mineral interests he had collected over decades. Under Texas’s weak legislative rules regarding disclosure of possible conflicts of interest, he didn’t have to reveal any of this.

Craddick got a friendly reception at the hearing: committee members thanked him for appearing, calling him “Mr. Speaker.” Mike Schofield, a Republican from Katy, reminisced about a trip he took as a schoolboy to the state capitol. “By the time I visited here at thirteen, the Speaker had already been in office for ten years,” he said. The committee asked Craddick no questions.

The bill passed both chambers of the Legislature, but it was vetoed by Governor Greg Abbott. “Texas prizes the freedom of parties to enter into private contracts and to have their bargains enforced,” Abbott wrote in his veto statement. The implication of his message was that the broker who received the overriding interest should have done a better job of negotiating, rather than asking the state government to bail him out. Late last year, ahead of the current session, Craddick reintroduced his bill. In late February, it was referred to the House judiciary committee and began to move through the chamber.

By constitutional design, Texas has citizen-legislators. Today they earn about $40,000 for approximately six months of work during regular sessions every other year. Almost all work at other jobs. It is not surprising that you’ll find chemical engineers, emergency room physicians, litigators, ranchers, and real estate investors serving in the Lege, often on committees where their expertise can be useful. But Tom Craddick is in a category all his own. His family’s mineral interests interconnect with Permian giants such as CrownQuest, Diamondback, Occidental, and Pioneer, as well as a number of smaller operators. The Craddicks make deals with these companies.

The statement we received from HillCo Partners said the Craddicks “fully comply with all Texas laws of financial disclosure.” That appears to be accurate. And it stands as an indictment of the state’s lax disclosure laws. The Craddicks have been movers and shakers in the oil industry for decades, but the extent of their holdings remained out of view until now. Their $10 million in earnings last year remained as deeply buried as a layer of oil-soaked Permian rock waiting to be liberated by the jolt of a perforation gun and the hydraulic force of fracking.

Meher Yeda contributed reporting to this story.

Disclosure: The chairman of Texas Monthly, Randa Duncan Williams, also serves as chairman of the general partner of Enterprise Products Partners L.P. As a major pipeline owner and operator, Enterprise sometimes has cases before the Railroad Commission. Enterprise’s political action committee contributed $10,000 to Christi Craddick’s campaign in 2021.

This article appeared in the May 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Gushers of Cash.” It originally published online on March 14, 2023, and has since been updated.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Legislature

- Longreads

- Tom Craddick

- Midland