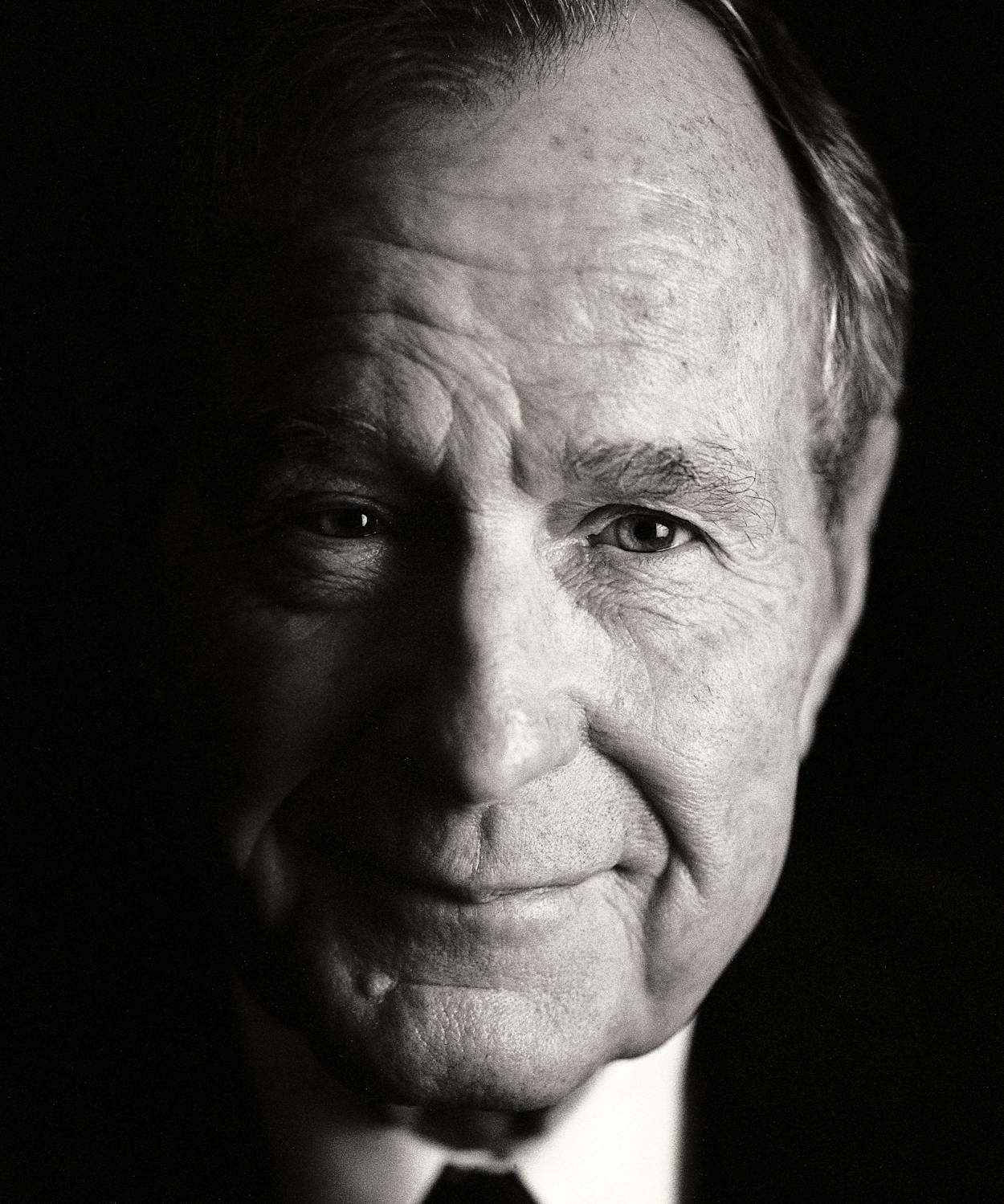

I always enjoyed watching George H. W. Bush and the media, both local and national, spar over one of the most contentious issues of the president’s life and times: whether he was a real Texan or not. Even a respectable (and generally respectful) publication such as this one got in on the act. “He was a lean and lanky six feet two, with crystal-blue eyes, neatly combed brown hair, and the kind of clean-cut, delicately handsome features that seemed to sing out ‘I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy,’ ” is how a June 1983 Texas Monthly article described a 24-year-old Bush, newly arrived in the West Texas oil patch in the summer of 1948.

There was no shortage of Bum Steer Awards calling into question his Texas bona fides over the years. In January 1985 we gave him top billing after he claimed that his real residence was his family’s compound, in Kennebunkport, Maine, so he could save $123,000 in taxes. “The IRS didn’t buy it, but we do,” we wrote. “Now we know why you spent the whole year acting like a Yankee. Anybody who’d sell his Texanhood for $123,000 deserves to be Bum Steer of the Year.”

Four years later, we gave Bush, by then the president-elect of the United States, yet another Bum Steer, this time for calling the presidential suite at the Houstonian Hotel his Texas residence during the campaign. Newspapers from the Los Angeles Times to the Toledo Blade also had a little fun with the story, much to the delight of Democrats, a group of whom rented out that very suite during their state convention to needle the Republican candidate.

Even in death, Bush has been haunted by the specter of eternal exile: “Forty-first president honored in adoptive home of Texas before being laid to rest,” announced a Wall Street Journal story after his Houston funeral. It was as if 41, as he was affectionately known here, was never allowed the privilege afforded to just about everyone else who settles in Texas, which is the honor of calling oneself a Texan without a modifier attached. Davy Crockett came from Tennessee, as did Sam Houston. No one has ever made fun of their claims to the Lone Star State.

Maybe Bush became a target because he came from a world most Texans have historically held in contempt: Yankeeland, specifically the Richie Rich environs of Greenwich, Connecticut, where his dad, Prescott (Prescott!), was an investment banker and, later, a Republican senator. And of course Bush went to that fancy-pants prep school, Phillips Academy, in Andover, and then, after a stint in the Navy during World War II, to hoity-toity Yale. There was also all that patrician stuff: the exceedingly good manners, the prolific writing of kindly notes (he once apologized in an email to me for declining to participate in a story about his son Neil’s bitter divorce). Real Texans for many years were thought to be guys like oilman Oscar S. Wyatt Jr., who shot hogs from his helicopter. Bush never got points for striking out for West Texas and building his oil business there beginning in the late forties, and anyone who has spent much time in Midland knows it makes Asmara look like an oasis.

Maybe the problem was that the struggle over his Texanness was internal as well as external. Bush’s life in Houston was often an awkward combination of old-money noblesse oblige and, well, the Texas thing. He had Texan interests if not quite authentic Texan tastes. When he and Barbara moved with their four children to Houston, in 1958, he was already on his way to being a millionaire, but he chose to live in understated Tanglewood instead of flashy River Oaks, where most other oilmen had made their home. He loved Mexican food but preferred the West Houston chain Molina’s Cantina, which has never been known for using serrano and jalapeño peppers in abundance. He loved barbecue too, but his favorite joint was the now moribund Otto’s, a homey dive near Memorial Park that was eventually eclipsed by far tastier spots in more racially diverse parts of town.

On the other hand, you have to give the guy credit for legitimizing the virtually nonexistent Republican party in Texas, a brave act for its time. Back in the day, says Dave Walden, a longtime political operative in Houston, “you basically had three kinds of Republicans: the John Birch Society types, who were really off-the-wall; the hard-core Goldwater people, who were very conservative; and the pro-business, moderate, try-to-get-along-with-everybody, try-to-keep-the-government-out-of-our-lives-type Republican—that’s where Bush was.” But it wasn’t until Bush agreed to become Harris County party chair and started barnstorming the state that people of the GOP persuasion thought it was okay to join up. As Mark P. Jones, a political science fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute, points out, “If you were a politically ambitious person, the strategic thing to do was run in the Democratic party, not to stick with your Republican brand and run as an outsider.”

Of course, even as he launched a political career, Bush had to make some changes to his image. He was stuck with the carpetbagger charge when he ran for Senate against the folksy Democratic liberal Ralph Yarborough, in 1964. As the presidential biographer Jon Meacham reports in Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush, the candidate had to give up wearing a necktie and using big words (like “profligate,” as in spending). He had to trade in his Mercedes for a Chrysler. He still lost, but along the way he won a lot of respect from people who weren’t members of the Petroleum Club.

Bush was at heart a sentimentalist, but he also came to display a pragmatism that seemed distinctly Texan. His move to the right during the Reagan years and during his own presidential campaign could have been (and was) described as expedient. But in Bush’s calculus it would also have seemed the most expedient way to maintain his own power and influence. He may have struggled initially with his electoral losses, but Bush was also one to pick himself up and start over, always looking forward and rarely back.

And like many Texans, his faith—albeit Episcopalian, not Southern Baptist—was never in doubt. “Unlike Bill Clinton or Barack Obama, his faith was a very public part of his persona,” Jones said. Bush taught Sunday school and had a family pew at St. Martin’s, in Houston. His devotion was genuine and unapologetic, as evidenced by the affectionate and knowing eulogy given by his minister, the Reverend Russell Levenson Jr., at the Washington National Cathedral. “They were not political members of that church. They were regular attenders,” Jones said.

That Bush wanted a second funeral, in Houston, was itself a testament to his adoration for the place he called home. He and Barbara had been prominent empty nesters here, socializing with longtime friends without big-dealing it, eating Chinese food at the Galleria, and attending Astros and Texans games. There seemed to be more local sports figures—Nolan Ryan, J. J. Watt, Yao Ming—on the funeral guest list than old-line Houstonians, though that may be because there were so few of the latter left. I don’t expect many people back in Bush’s hometown of Greenwich would have ever arranged for a musical tribute by the Oak Ridge Boys and Reba McEntire. But Bush wasn’t a stuffy guy.

And in the end, there was the choice of his final resting place. Bush did not pick the family compound in Maine after all, but Aggieland, a place that many would declare the most quintessentially Texan spot in all of Texas.

I say it’s time to cut the guy some slack. Welcome home, George, forever and ever and ever.

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- George H.W. Bush