In the early 1850s a small contingent of German immigrants journeyed into the heart of the Texas Hill Country, claiming a piece of land a few miles southwest of the recently settled community of Fredericksburg. Among them were the artists Hermann Lungkwitz and Richard Petri and their extended families. Lungkwitz and Petri, who were brothers-in-law, chose as their new home—a place to build log cabins and to farm—a stretch of fertile upland that overlooked a sweeping bend in the Pedernales River.

Their surviving landscape paintings depict this piece of land in the spring: the rough-hewn cabins, the wildflowers scattered blue and scarlet and gold across the hill and flowing down to meet the trees at the curving river’s edge—an idyllic setting when viewed more than a hundred years later in an air-conditioned gallery at the Institute of Texan Cultures, in downtown San Antonio.

Or perhaps not so idyllic. In 1848, a few years before Lungkwitz and Petri claimed their farm, the Army established Camp Houston—soon after renamed Fort Martin Scott—on the outskirts of Fredericksburg “to protect Texas settlers from Indian depredations.” Looking closely at those landscape paintings and sketches, it’s impossible not to notice how vulnerable their primitive log cabins must have been. One can only imagine the many uncertain nights they spent there. And the lovely landscapes fail to capture the inevitable droughts, the surging river floods, the untimely frosts, the invasions of grasshoppers, and the swarms of mosquitoes.

Petri later drowned in the unpredictable waters of the Pedernales as he sought relief from a high fever. A small plot on the property, nestled under the overhang of some live oak trees, holds his grave.

When my wife, Lynn, and I bought this acreage in 1983, we knew none of this; we would unearth this history layer by layer over the next few years. By the time we arrived, the log cabins had disappeared, but a no-nonsense house built in 1878 to take the cabins’ place still stood. The house, strategically sited a few hundred yards back from the floodplain of the river, was erected with eighteen-inch-thick blocks of limestone.

We first saw the place on a bright, cold day in December, the wind whipping down from the Panhandle. A few cows and calves huddled by the back door, bawling for a handout of range cubes or a bale of hay. The land all around was overgrazed and winter-bare, and the newer outbuildings—a two-story plank barn and a rickety chicken house constructed decades earlier—had weathered to a dismal shade of gray.

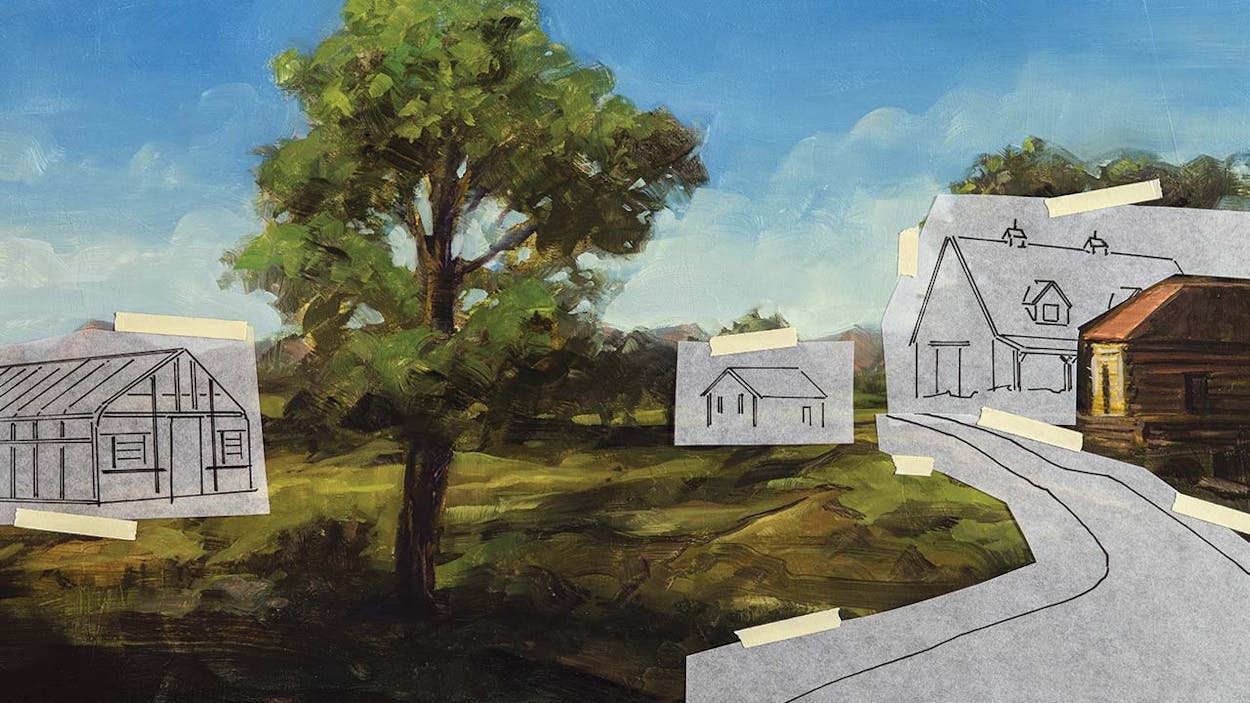

But the sun gleamed off a stone barn out back, and down the hill we caught flashes of the shallow river as it rippled by. Perhaps because I was at a point in my life when I was ready to welcome change—even difficult and perhaps foolhardy change—I began to visualize the transformation of the house, the way it might be. The house still possessed solid heart-pine floors and stable stone walls, and the interior damage caused by a worn-out roof was superficial, not structural.

After the first walk-through, Lynn gave me a skeptical “What do you think?” kind of look. I took a deep breath and plunged ahead, not knowing exactly what lay before us but not wanting to go back to San Antonio to face the still-reverberating crash of the oil-based economy. I wanted an herb farm, a place to work the land, a place to act out some of those back-to-the-earth fantasies repressed since the sixties.

“Well,” I said. “We would need a deep well and a new septic system.” I looked around. “We’d have to replaster those walls.”

“Or,” Lynn said, with sudden enthusiasm, “strip that plaster off and expose the stone.” She glanced up the stairs. “And the attic, with its high ceilings? Plenty of space for three bedrooms up there, with a bath.” By now Lynn, too, had moved into a dream state. This was getting serious.

“A big project,” I said. “You ready for this?”

She smiled and nodded.

So we were off, committed to one hundred acres of land and a 105-year-old house. A new beginning. We stared out a front window toward the Pedernales, the landscape distorted, wavering through the imperfections of the aged glass. “River Bend Farm,” I said. “Yes,” Lynn agreed. “River Bend Farm.”

Lynn, an artist with an eye for design, took charge of restoring the house while I tackled the land, hauling off years of accumulated junk. I dug herb beds and trucked in soil. I found a greenhouse that could be ordered unassembled, and we put it together in a couple of days.

By March the greenhouse had become my second home. For rigidity and strength and light distribution, its fiberglass panels were alternately concave and convex, which threw washes of light in patterns this way and that depending on the angle of the sun.

One morning, the smell was organic—soil, plants, compost. The sun refracted across the flats of seedlings crowded onto wire mesh–topped platforms. The only sound was my own breathing and the hum of a propane heater. There, at that moment, I lost myself in the soothing monotony of transplanting seedlings into pots, taking an occasional break to search for the first green curl of new shoots breaking through the friable soil. I took cuttings from a dozen scented geraniums; the air filled with rose and cinnamon and apricot. With a fine spray I watered lemon balm, seven varieties of basil, and a scattering of flowering perennials. The greenhouse blossomed rainbows in the mist.

All morning I worked, my hands deep in potting soil, my mind clear, free to wander here and there, to places of ease, without consequences. I took more cuttings: English and French lavender, Greek oregano, and a pink-blossomed rosemary.

At mid-morning I shed my jacket and filled flats for tomato and pepper seeds, going over in my mind the promises of catalogs, seeing once more those slick red and green reproductions, admitting to myself that, yes, I had overordered.

At eleven I looked over the morning’s work, propped open the greenhouse door, and stepped outside. The country landscape lay winter drab. My eye followed a fencerow waiting to be cleared of brambles, found trees to be trimmed of limbs broken in a recent ice storm. I surveyed a crumbling rock wall I had sworn to restack. Maybe tomorrow.

I turned back to the greenhouse, needing to recapture a few more minutes of the morning’s pleasure, but the day’s magic had vanished and couldn’t be reclaimed, so I trudged back toward the house.

In early May the greenhouse burst with color: enough parsley to border the herb beds, along with assorted vegetable starts. Soon we had herb gardens and a rose garden, a place for early spring irises and daffodils, and almost an acre of vegetables. That first summer we sold vegetables and pots of herbs from tables set up under the wooden barn’s overhang. Once a week I hauled produce to upscale grocery stores in Austin and San Antonio. Lynn cut and bundled flowers and herbs that we hung upside down to dry from the rafters of the stone barn.

The first two years streamed by. In time, area newspapers ran Sunday features on River Bend Farm, then regional and even national editors called and staged parties to be photographed for upscale books and magazines. Our Hill Country farm was famous! But still, after working seventy-hour weeks and hiring only minimal outside help, we found ourselves slowly falling behind financially.

During our third winter we came up with the idea of starting a country inn, and on the outskirts of town we found the perfect house for our purposes. A few weeks later we watched nervously as the house mover eased our future inn over the river’s low-water crossing and settled it near some live oak trees not far from our home.

We dreamed, and, at first, the dreaming seemed good.

Then, one summer evening, after scrambling to save flats of greenhouse starts from an unseasonable 100-degree day, I sat on the porch with my wine glass and stared out into the night. The soon-to-be inn glowed in the moonlight, and suddenly I envisioned the way it would be—really be—with the inn’s lights all bright and cars parked out front and someone calling at the last minute to cancel a reservation, a lavatory not draining and breakfast to be prepared before daylight and someone allergic to the nuts in the muffins. Then the dirty sheets and me standing over a toilet with scrub brush in hand. And all those people, when what I wanted was my coffee and my wife and my cat. And some quiet. No. I couldn’t do it.

I moved to the back door. “Lynn,” I said as calmly as I could. “Would you join me for a few minutes? And please, bring the wine.” We are both conceptual, creative people and the thought of day-in, day-out maintenance bores us. With obvious relief, Lynn agreed that it was time to leave.

We sold River Bend Farm. We moved on, geographically—out west, to Arizona. But we moved on in other ways as well; we were ready for what might happen next.

Recently I looked back through our River Bend Farm scrapbook. There we are, Lynn and I, thirty years younger, posing in front of the stone barn, hosting a photo-op party for the editor of a splashy East Coast coffee-table book. There are the herb gardens, the multitude of sage and rosemary plants blossoming blue and pink and crimson against the glow of our white picket fence. But I know what is hidden behind the glossy pages.

I think of the landscapes that Lungkwitz and Petri painted of that place more than a century and a half before and the beauty, the tranquillity, that their paintings evoked, and I know—romantics that they were—what they dared not paint.

Maybe that is how it should be, for why would I want to call up those times when it never rained, or the rising river blocked the only road to town, or we battled crabgrass and fire ants?

What I want to remember is the quiet and solitude, the honest, hard labor that produced moments—even days and weeks—of pride and pleasure. Sometimes it’s better to say no, to move on, before all you have left are the regrets of staying.