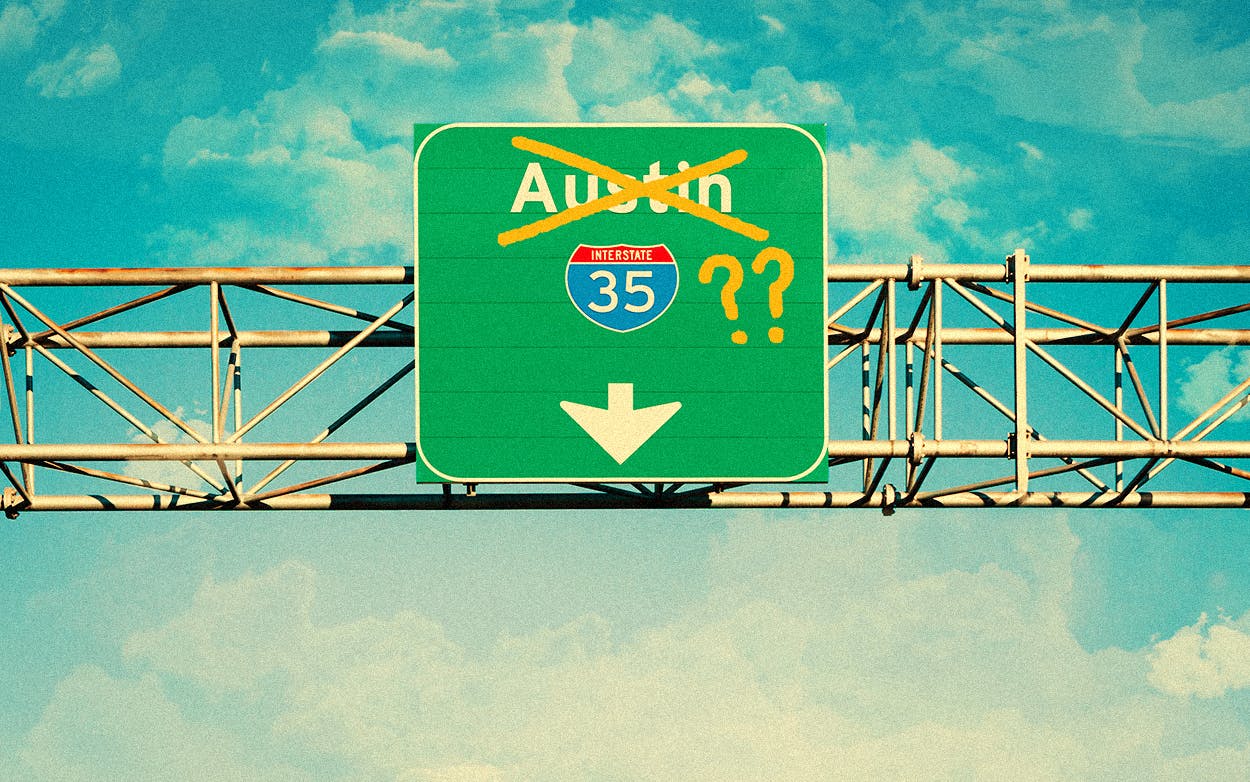

Last week, Austin’s Equity Office raised some eyebrows when it released a 25-page report highlighting locales in the city named for the Confederacy. The report is part of a resolution, which was passed last year, to remove memorials and markers related to the Confederates. But the report was broader than names on street signs. The document came in two lists: one of “initial review” assets, which included suggestions for immediate action, and another for “secondary review” assets. These streets and other city institutions weren’t directly named in honor of the Confederacy, but they “were within the spirit of the resolution representing segregation, racism, and/or slavery.” And there was a big one on the latter list: the name “Austin” itself.

The city’s namesake, of course, is Stephen F. Austin, the “Father of Texas.” Austin defended slavery, opposing Mexico’s efforts to ban the practice and arguing that emancipation would lead to formerly enslaved people becoming “vagabonds, a nuisance, and a menace.” That certainly fit the “secondary review” criteria, but the idea of renaming Austin because of the association drew headlines—and also mockery. The San Antonio Express-News solicited reader suggestions, which included “Bedwetterville” and “New California.” USA Today published an op-ed with the headline “Politically correct effort to rename Austin proves Donald Trump was right.”

But the report isn’t actually an effort to rename Austin. “I don’t know anyone who is seriously championing to change the name,” David Green, the city’s media relations manager, told the New York Times. “There are things in our past that we may want to acknowledge and look at, but that doesn’t mean you want to rename a city, especially one named after someone who founded a republic that then became a state.” A change.org petition urging the city to return to its long-ago name of Waterloo has a whopping fifteen signatures at press time—and it was started in February. Austin’s inclusion on the list is neither an effort nor a proposal—just an acknowledgment that, if the city wants a full accounting of every slavery-related asset in its midst, it qualifies.

A name change would likely be expensive. There are no clear estimates on the cost, but you could find a baseline in other relatively recent and significant name changes. When the World Wrestling Federation lost a 2002 legal challenge from the World Wildlife Foundation and was forced to re-brand as World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), it cost an estimated $50 million to fully implement. The people of eSwatini—which, until April, was known as Swaziland—may get away with shedding their colonial name for less. The rebrand for the largely agricultural nation (which, with a population of 1.5 million, is not much larger than Austin) is expected to cost around $6 million.

Those costs aren’t just about signage and logos. A city like Austin, which has invested so much in marketing itself globally as a business/tourism/creative destination would have to spend a veritable fortune recasting the image.

Of course, a lot of the advertising around a name change would be free. There’d be headlines around the world—both outraged and laudatory—about any effort to address racial grievances and grapple with the most reprehensible part of America’s history through such a dramatic move. Certainly, the “New California” slams and handwringing about political correctness run amok would abound. But Austin—especially by statewide leaders in Texas—receives that kind of reaction anyway. Last summer, Governor Abbott addressed Bell County Republicans and bashed the capital before an appreciative crowd. “Once you cross the Travis County line, it starts smelling different. And you know what that fragrance is?” he asked. “Freedom. It’s the smell of freedom that does not exist in Austin, Texas.” So what would the city really lose if George P. Bush found it to be “an insult”?

Without Stephen F. Austin, there’d be no Texas. To rename the City of Austin would be an insult to his legacy and all those who fought for Texas independence.

— George P. Bush (@georgepbush) July 30, 2018

Of course, the backlash wouldn’t just come from conservatives. People are resistant to change. Residents on the streets named for Robert E. Lee and Jeff Davis, in deep blue precincts in Central Austin were probably not strong proponents of the Confederacy—but some disapproved of the new name anyway. (The city council, in making the change, observed that few of those who gave feedback opposing it bothered to register their opposition in person at the meeting, where the move was more broadly supported.) Even in the egregiously-named Tarrant County town of White Settlement, voters rejected a name change 90-10 in 2005. “Austin,” whose racial implications are far more abstract, would presumably have a tougher road.

Austin has very real problems around race. The city is one of the most segregated in Texas. Its black population has been steadily declining and pushed out to the suburbs. Businesses and property owners tend to treat the much-celebrated cultural heritage of its white residents differently than that of its black and Latino citizens. Those things won’t be fixed by renaming the city Waterloo, but the haste with which the city’s spokesman dismissed the idea of a rechristening is telling.