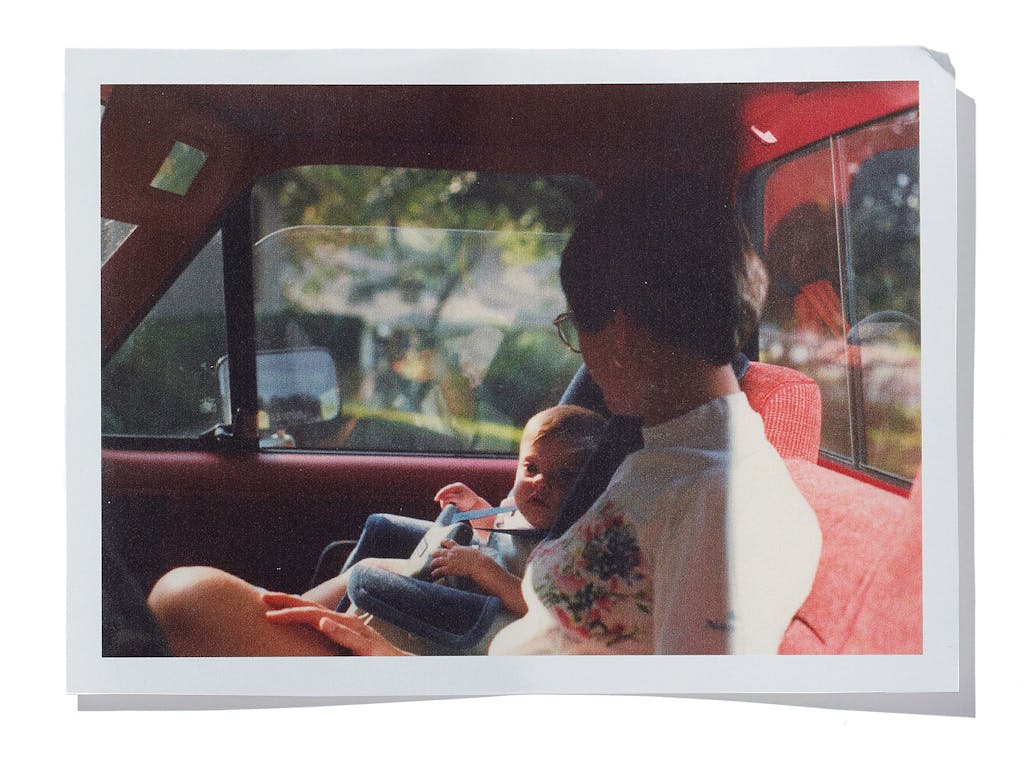

Every morning, just before heading out into the predawn light to her job as a dentist for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, my mom would hunch over the laminate countertop in our dimly lit kitchen and scribble a note for me. She would neatly place it in my lunch box, which she also packed each day. Later, when I would plop down on a long bench in the cafeteria at Huntsville’s Gibbs Elementary School, I would rummage through my smooshed turkey sandwich, Dole fruit cup, Ruffles potato chips, and single Hershey’s Kiss, and—without fail—find an extra napkin marked with her unkempt cursive.

Often she wrote to tell me, as she always did before I left the house, to be “gentle, sweet, and kind.” Other times, prompted by my teachers, she urged me to stay quiet in class, despite the fact that she adored my tendency to randomly break out in song. On Fridays she would remind me of our weekly ritual: an after-school trip to King’s Candies, downtown on the Huntsville square, where we celebrated the beginning of the weekend with a BLT and a bag of pastel-colored mints we plucked out of rows of giant glass candy jars. It didn’t much matter what the note said, though. It was my mom’s way of reminding me that she was always there.

Of course, other kids got occasional notes in their lunch boxes: encouragement for a math test, a simple “I love you” in flowery script, goofy renderings of smiley faces, the occasional lip-mark in a shade of red that could only have belonged in an East Texas cosmetics bag. But for my mother, who found order in quotidian rituals, the extra napkin wasn’t simply an afterthought; it was as much a part of my lunch box as the meal itself.

My mom had a particular attachment to handwritten notes. The joke among the blue-haired ladies at First Baptist Church was that if you ever did anything nice for my family, you’d better hurry home if you wanted to beat Cinde Johnston’s thank-you card. Years ago I found a note tucked into one of my dad’s college textbooks, A History of Soviet Russia. It was an apology written by Mom, then a newlywed, for losing her temper the night before.

So it wasn’t all that surprising when a letter arrived in our mailbox a few weeks after her funeral. It was addressed to me, a third-grader at the time. It was a note from Mom.

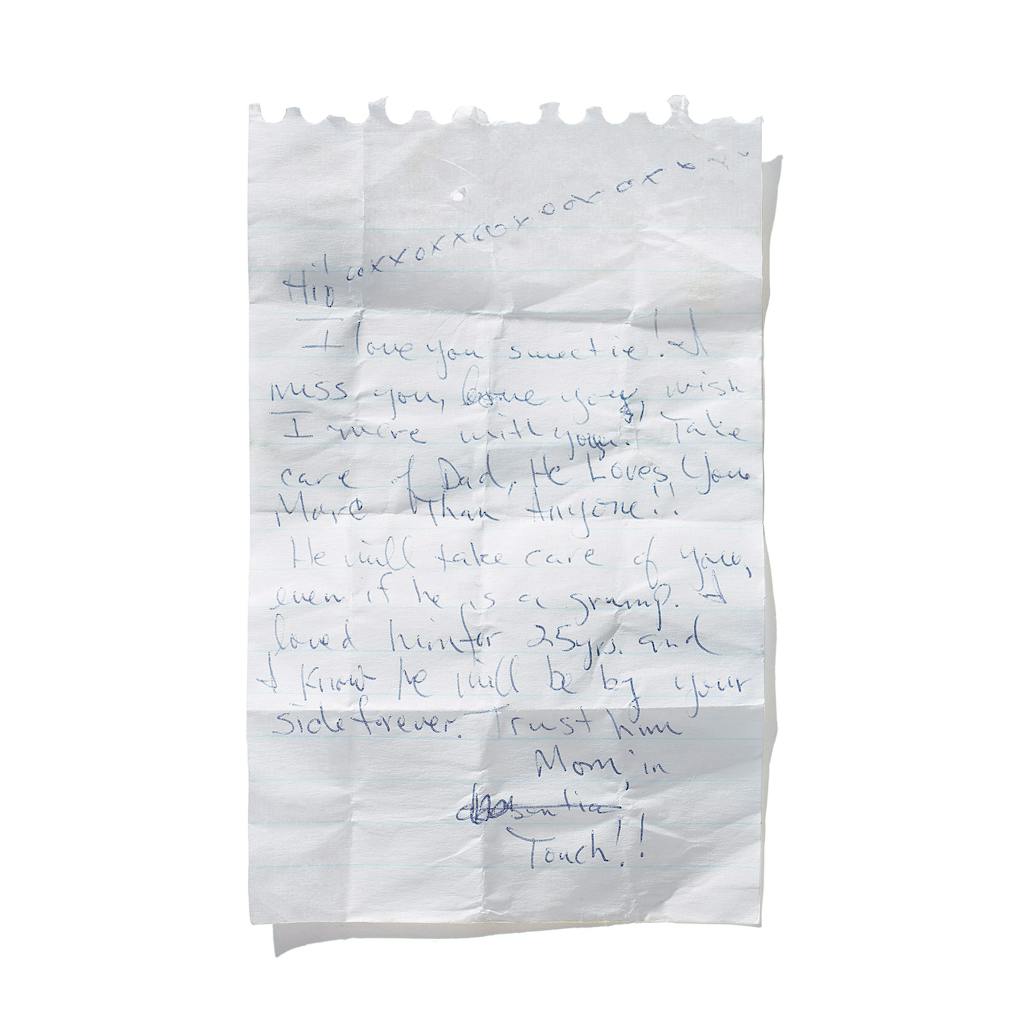

My first memory is of my mom. I was around four, spending the day in Houston with my paternal grandparents, who had traveled from Arlington to help my dad during one of Mom’s extended stays at MD Anderson Cancer Center. We made our way to the top of a multistory parking garage so I could glide along the empty expanse of concrete on my tricycle and roller skates. Granddad, who had been staring off into the distance as Mimi watched me turn circles, eventually called me over to the edge. Mimi followed, bracing herself against the concrete barrier as Granddad hoisted me onto his hip and pointed. It took several moments for me to spot a woman waving—her short, curly, dark-brown hair gone, completely shaved—behind one of the hundreds of shiny glass squares in front of me. It was the first time I’d seen my mother in weeks. I don’t know how long both of us lingered like that, waving to each other, but in my memory I can still hear my grandmother start to cry.

Other memories of Mom exist in short, blurry flashes, like an old home movie that fades and flickers over time.

Many of my childhood memories are set in Houston, an hour and a half from home. I made regular trips there with my mother, and I looked forward to those car rides to the city. When we left, hours before the sun came up, it felt like we were somehow sneaking away from something, embarking on an adventure together, just Mom and me. She would stop and buy me doughnut holes at the first open bakery she spotted, and I would happily munch on them as I gazed at the stars still in the morning sky, wondering how the dark could persist if we had entered a new day.

She often scheduled her hospital appointments on weekends so we could visit the Houston Zoo or Six Flags AstroWorld (my mother, even during her weakest moments, remained a roller coaster enthusiast). And she would frequently go out of her way to drive by Rice University. She firmly insisted that one day I would be among the throngs of students strolling across its verdant campus, suggesting more practical majors than the French and journalism degrees I would eventually pursue.

Other memories of Mom—those outside the context of an endless succession of doctor’s visits and chemo treatments and breast scans—are harder to come by. They exist in short, blurry flashes, like an old home movie that fades and flickers over time. I remember sitting with her on the banks of the Comal River in New Braunfels when I was seven years old, watching inner tubes tumble down the Prince Solms Park chute, the waterslide carved into the side of the city’s dam. During our annual trips to the river, we typically rode the chute together, me in her lap, but that year the port in her chest, which had been implanted for chemo treatments, kept her from getting into the water. Instead, as children of family friends rode the rapids over and over, we were both content to watch from the sidelines. I buried my face in her neck, taking in the scent of sunscreen on her tanned skin, and asked if next year we’d be able to ride the chute again. Mom, her hair only just starting to sprout back, could only offer me, “Maybe, honey. We’ll have to see.”

Another memory: we’re wading through a creekbed on the outskirts of Huntsville, dappled sunlight filtering through the towering East Texas pines. As I bounded ahead, Mom, whose body was starting to slow, shouted after me, reminding me to be vigilant in watching for water moccasins. I recoiled in horror, rushing back and clinging to her waist, but she took my hand and said, “I’ll look out for them too.” We spent most of the day splashing and lounging along sandy stretches of the creek, my mind completely at ease, making whistles out of blades of grass.

I have managed to hold on to some other specifics. I remember her clear alto ringing out both in church (particularly prominent on her favorite hymn, “On Eagle’s Wings”) and in the car (she preferred the Beatles and the blues outside of the sanctuary). I remember her absurd hats lining a wall of our guest bedroom—my favorite was an electric-blue sequined beret. I can feel the comfort of her arms wrapped around me after getting my finger pricked by a cactus in the basin of Big Bend National Park. And I can still replicate our special whistle—starting high, then a quick slide down the scale before leaping back up to the original note (if she wanted my attention when I was small, it was as good as a dog whistle).

But these memories are difficult to preserve. The main truth that I hold about Mom, which will inevitably come up in every conversation I ever have about her, was that she was very sick. And then she died.

On May 12, 1999, a week after my ninth birthday and three days after Mother’s Day, my mom left this world at age 43. Breast cancer, which had slowly spread through her body for seven years, finally overtook her, and she died at home, in her bed, with my father next to her. Of all of the things I struggle to call to mind about her, it seems cruel that I remember that first morning without her so clearly. My dad lightly tousled my hair, the lights still off in my bedroom, a soft glow coming from the hallway. I blearily glanced at the clock—it was around seven in the morning—and then bolted upright, panicked that I was late for school. He grabbed me by the shoulders as if bracing me against something. His eyes were filled with tears for the first time I could ever recall. He leaned in and whispered, “She’s gone.”

When the letter from Mom arrived a few weeks later, it was postmarked from heaven. I imagined that after she’d written it, stuffed it into an envelope, and let it slip from high above, the letter had dodged fluffy cumulus clouds on its way to our home. It took me years to understand that my dad had placed it in the mailbox. (At least, I assume it was my dad. Nearly two decades later, he’s still not one to talk about these things.)

In the first days and weeks and months after Mom’s death, I did my best to maintain a shred of normalcy amid funeral planning, the parade of family members and friends, and navigating my first summer without her. The note from Mom, not unlike the ones she stuffed in my lunch box, helped. The need to impose order is something my mom would have understood instinctively. After a troubled childhood and a cancer-stricken adulthood, she regimented every possible aspect of her life to try to maintain some sense of control. Looking back, I realize it’s a coping mechanism that I developed as well.

In the letter, Mom assured me that she was no longer hurting, that her death had been a release. It’s precisely the thing that our friends and family had told themselves—and me—to make her death feel like less of an injustice. At the time, I readily accepted her explanation. My frustration came when I realized I had no way to write her back.

I gradually began to stumble across handwritten notes elsewhere. In the year leading up to her death, Mom, ever the fastidious planner, had strategically hidden them all over the house.

That was the only time a letter from her showed up in the mailbox, but I gradually began to stumble across handwritten notes elsewhere. In the year leading up to her death, Mom, ever the fastidious planner, had strategically hidden them all over the house. I found one that December, my first Christmas without her—the same year Dad got me a puppy, something Mom had always forbidden—hidden in a tiny mailbox ornament. (She must have known the holidays were going to be especially hard.) Over the years I found them secreted away in jewelry boxes and stashed among toys. There were many in my favorite books; Mom knew it was better to hide them there than in my neglected box of Barbies. When I was fifteen, while searching for childhood photos of myself for a project with my dance team, I found another tucked inside a photo album that had been sitting at the top of my closet for years. The notes came unexpectedly, and with them, electric shocks of realization: they often turned up when I wasn’t searching for anything at all. The few times I tore through my possessions in moments of desperation or longing, trying to apply logic to her hiding spots, they never surfaced.

Yet they appeared frequently enough that, as a child, I never lost faith that another note awaited me somewhere, that Mom had left one in yet another random nook I’d never think to search. After all, until she died, Mom wrote to me in some form every day, even if it was a command scrawled on a church bulletin to stop fidgeting as I sat on the pew next to her. The hidden notes felt like a natural extension of that communication.

But as I grew older, as more birthdays passed without her, I came to the realization that the notes eventually had to end. In my teenage years, I was gripped with anxiety each time I encountered one, fearing that it was the last vestige of our shared history. I’d grown increasingly conscious of the fact that my memories of Mom were slipping, like a foreign language fading in stagnation. I’d forgotten what her perfume smelled like. I could no longer map the constellation of moles on the back of her neck, and even the details of her face began to blur in my mind’s eye.

At the same time, I was morphing from an oval-faced kid into something resembling an adult, one who looked and behaved much like my dad (I still chuckle every time I see my parents’ wedding photos—my twenty-year-old father was, essentially, me in a tux). At every milestone I was becoming ever more distant from the girl that my mom knew. Those notes felt like our only remaining connection.

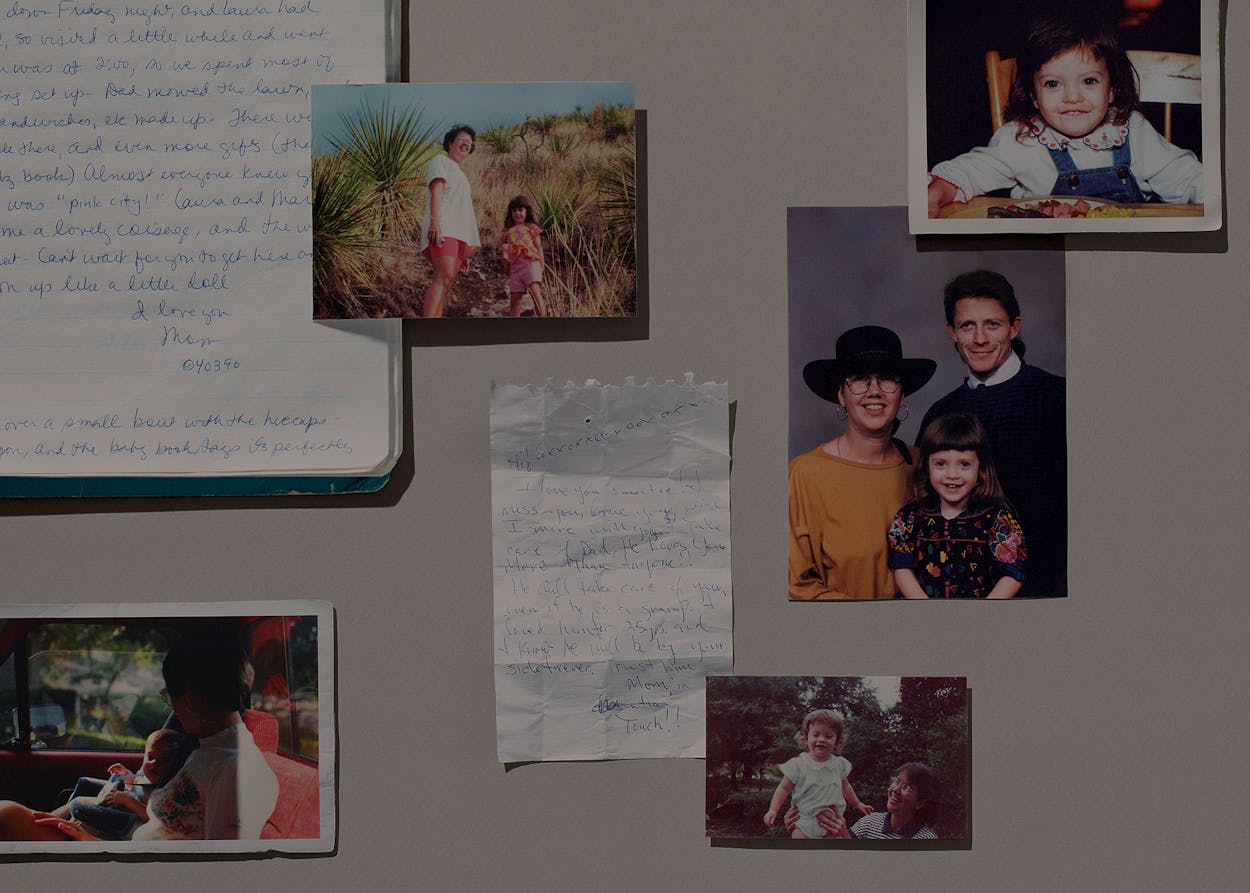

I discovered the last of them as I packed for graduate school, in 2013. I was headed to study journalism at the University of Missouri, a far cry from the law or medical degree she had hoped for. In my South Austin apartment—my first address after graduating from the University of Texas at Austin—I sorted through the parts of my life that I wanted boxed up and hauled, along with my cat, to Columbia, Missouri. I’m both hopelessly sentimental and a pack rat, so moving is a particularly painful process—every tchotchke was a reminder of family, friends, or the home state I was about to leave behind. As I turned out the contents of a plastic storage box filled with Christmas ornaments, a tiny scrap of paper floated to the floor, alongside the gaudy felt doves and nutcrackers made by my great-grandmother. It had been ripped from a small spiral memo pad and adorned with the soft ink of an already-failing pen. It was creased and folded many times over, but I recognized the handwriting instantly:

Hi!

I love you, sweetie! I miss you, love you, wish I were with you. Take care of Dad, he loves you more than anyone!! He will take care of you, even if he is a grump. I loved him for 25 years, and I know he will be by your side forever. Trust him.

Mom, in absentia touch!!

I sank into the carpet and started to cry, my shoulders continuing to heave even as the sobbing dissolved into laughter. It was the first time I had found a note since leaving my home in Huntsville five years earlier, and it had been fourteen years since Mom’s death. I was in shock, but I shouldn’t have been. My mother always dropped in right when I needed her. My shoulders still convulsing, I called my dad. He seemed surprised only by the seeming inexhaustibility of the supply of notes. How are you still finding those?

I immediately stashed the note in the mahogany chest where I also kept Mom’s Mikimoto pearls. I was a disorganized kid, so over the years I had managed to lose her early messages, and the others had been misplaced during one of my five college moves. It was a devastating loss—the older I got, the more I longed for a small piece of my mom to turn to when I needed her. So I was determined to keep this one.

Three months later, after wrapping up my first semester of grad school, I headed home to Huntsville for winter break. Dad called me to his bedroom one afternoon and pulled a teal, dog-eared WriteRight three-subject spiral notebook out of his skinny chest of drawers. He unceremoniously handed it to me. “I thought I told you about this a long time ago,” he said with an almost aggressive nonchalance. (My dad was never one for sentimentality.) I opened to the first page, instantly recognized the handwriting that I’d studied and parsed for years, and looked back up at him for answers. “She kept that for you.”

I held in my hands nine years of diary-style entries from my mother, dating from the time I was still forming inside of her until the final months before her death. These weren’t the brief messages that I’d stumbled upon for years. They were letters, addressed to me.

What do kids know about their mothers? At best, platitudes—the kinds of descriptions I had once written on handmade Mother’s Day cards in my elementary school classrooms: nice, pretty, smart. But a child’s true understanding, the acceptance that emerges between two adults who have seen the world for all its ugliness and wonder, doesn’t come until they are much older.

Growing up, I watched in bewilderment as my friends started pushing away from their parents in typical teenage fashion. By contrast, I desperately sought more information about my mother. Through friends and family, I filled in the details of her backstory. She grew up in Alvin, some thirty miles south of Houston, and was the oldest of seven children. Her father left when she was a kid, and her mother dropped in and out, so my mom spent many of her teenage years taking care of her siblings. When she was sixteen, her grandfather shaved the lice-infested heads of the four youngest siblings and put them up for adoption. I know that Mom was stricken, but I also wonder if she felt some relief.

I know she married my dad—the middle son of a Southern Baptist preacher—at eighteen, in a modest ceremony, in a borrowed wedding dress, with my paternal grandfather officiating. I know that no one expected her to amount to much more than a waitress at Merle’s Diner and Pharmacy, her first job out of high school. I know that she and Dad spent eight months on the West Coast, where he worked as a land surveyor, before they moved back to Texas to attend Sam Houston State University. And I know that my mom, defying her upbringing, later graduated from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio’s School of Dentistry. She was its first female class president.

Degree in hand, she moved back to Huntsville with my dad; an old boss of hers had promised her a job at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. She worked for the TDCJ for the next eleven years, treating prisoners across the seven units in the Huntsville area. It was a practical decision—a reliable paycheck in a town where the economy revolves around the prisons—but she also grew fond of the men she cared for.

I have been told countless times, both by the people who knew her best and the ones who only passed through her life, about her generosity and kindness. I’ve read a letter from an inmate in the Estelle Unit, the super-maximum-security facility, thanking her for her compassion. “An individual must have respect for himself to ever love and respect others, and your friendliness to the men here is a first step in that direction,” he wrote. “To know that not everyone has condemned us for life.”

I’ve read the transcripts of a conversation dutifully recorded and preserved by my grandfather, who used it in the eulogy he delivered at her funeral. “I want to tell you what Cinde did for me,” a young prison guard told Granddad while standing in the driveway of my childhood home, one of many who gathered there, swapping stories after her death. “I work in the building where Cinde worked. Cinde was always smiling. She would come in every morning, smiling, and would greet me. This went on a while, and one day she turned around and came back to me. She reached up and with her fingers, pushed at my mouth and said, ‘Why don’t you ever smile? I smile and greet you, and you never smile.’ She saw my mouth and my teeth and said, ‘Come by my office in town, and I am going to fix your teeth.’ I was so ashamed of my teeth that I never smiled. She gave me my smile.”

These stories make me proud, of course, but after nearly two decades without Mom, I still digest them for what they are—a biography. They are the mythos of a larger-than-life woman, a person I can admire but never truly know. When my dad handed me that teal notebook in his bedroom, it seemed like an opportunity to change that. And so I was surprised when I didn’t immediately bound downstairs and pore over the entire thing. I convinced myself to savor it, to wait until the perfect moment to crack it open. But days passed, then weeks. I returned to my life in Missouri. Classes resumed, and still the notebook remained closed. Eventually I realized that I was afraid to read it.

Any young child who loses a parent spends their life asking questions that will ultimately be met with silence and doubt. For me, they cropped up with an increasing persistence the older I grew: Would we have been close? What was she really like? Would she love the adult version of me like she had loved the child? And, of course: Would she be proud of who I have become?

The trouble with knowing the end of a story while you’re still reading it, of course, is that it strips it of its hope.

The notebook offered the possibility of getting to know my mother as a fully realized person, something I’d always craved. But it also stoked fears about whether I would have disappointed her. After all, I’d gone to the University of Texas, not Rice. I had no interest in medical school. How else had I veered from the path she had envisioned for me?

One winter night back in Columbia, besieged by a sudden wave of homesickness, I finally decided it was time. I opened a bottle of wine and pulled the notebook out of a drawer in my bedroom. I took a deep breath and began to read. Two hours passed. Snow piled up outside. I drained the bottle of cabernet sauvignon as I sped through page after page, and finally I came to an entry dated February 23, 1999. It included a mundane account of my performance in the final round of the school spelling bee. “You misspelled ‘initial,’ and I claim it’s because you may not have ever seen the word written, since Dad and I called out the list (600+ words) over a period of weeks,” she wrote. And then she signed off: “Well, hon, I’ll write again soon. Love, Mom.”

Except she didn’t. The rest of the pages were blank; she died less than three months after that final entry. I snapped the spiral shut. “Mom!” I cried out, almost expecting her to answer. There was nothing but the wind and creaking of my small apartment, which suddenly felt cavernous.

As a kid, I had spent endless hours studying photos of my mom and probing people for information about her, but the pain I endured while reading her notebook was beyond comparison. I didn’t so much as glance at it for another six months. When I finally summoned the courage to return to it, I was shattered once more. I deposited the notebook back into the drawer, where it remained undisturbed for another few months.

Eventually something shifted within me. At first I’d consumed the notebook so rapidly that the fact of its existence—that it was here, and my mom was not—was all that registered. But I began to slow down. I wanted to understand the letters more deeply, to see what she might have been trying to tell me. I began treating the notebook as a scholarly endeavor. I read it the same way I analyzed a novel for class discussion, searching for clues that might reveal hidden meanings. Essentially, I was looking for all the things that friends and family had failed to impart.

In her early entries, Mom’s writing was clearly fueled by surging pregnancy hormones. “Hang in there, Abbey,” she scribbled on December 28, 1989, the first letter in which she had given me a name—even if she hadn’t settled on a final spelling. “Four short months and you’ll be here for us to love with our arms (we already gave you our hearts).”

I noticed the first time she referred to herself by her new title, ending an entry on February 11, 1990, with “Love, Mom.” Flipping through the following pages, I could see her becoming a mother.

May 8, 1990

Dear, sweet Abby,

I know you’re sweet because you’re here! This is your third full day in this big world, and I can’t express on paper how very full of love our hearts are for you.

. . .

We are absolutely enchanted by you, little girl, and I don’t know if you’ll ever have the same experience or feelings, but I sure hope so. God made a miracle for us, and I hope we can be worthy of this blessing.

Love,

Mommy

I was taken aback by the heightened degree of sentimentality in her words. I adored my mom, but as a kid I also feared her. She wielded a you-know-what-you-did stare that could reduce me to instant tears. She was generous and kind but also stern. The saccharine tone of the letters was largely unrecognizable.

May 12, 1990

Dear Abby,

This is a “stolen” moment. You have completely changed our previously unscheduled life, and you’re asleep right now, so I’ll jot a line or two.

Each day you’ve become more special. Can this go on forever?

The trouble with knowing the end of a story while you’re still reading it, of course, is that it strips it of its hope. Nine years later, to the day, she would die.

As I continued reading, I discovered some of her first pangs of parental guilt as she prepared to return to work, when I was six weeks old. “Abby, Mom went to school a long time to become a dentist, and there is really not a way I can stay home with you. When you’re older, and understand more, maybe my hours will be flexible enough to spend time with you.”

I noticed how her handwriting—usually loose and loopy—collapsed into itself on October 5, 1992, when she set in ink that “Dr. Atkins called me @ work and said that the lump looked suspicious.” In the large gaps between the entries that followed, I filled in the timeline with the kinds of treatments she was undergoing.

Part of the notebook’s power, I realized, was that it supplemented my own memories of my nine years with her. I hadn’t forgotten how much I used to hate swimming lessons, but one letter reminded me of the time she showed up at the pool after she’d been hospitalized for three weeks: “When I got home from the hospital the first day, we surprised you. I was waiting in a chair while you took your shoes off. I whistled our special whistle, and you looked around quickly then ran over and gave me about twenty kisses (you’re not much of a lover). I ate it up!”

In my mind, Mom had always been bald, with scar tissue where her left breast used to be. I never knew a time when she didn’t spend long stretches at the hospital. I knew that cancer was serious, but I didn’t have the emotional tools to understand what a threat it was. More importantly, I never understood just how scared she was. Still, even as a kid, I’d wanted to shoulder some of her fear and hope, to share the weight of her burden. But here’s something else I learned: Mom was determined not to let that happen. In the first moments she learned of her cancer, my mom was not thinking about the pain or the treatments or the daunting uncertainty. She thought about me: “We were pretty devastated,” she wrote. “We didn’t know what to expect. I wasn’t really frightened per se, but Dad was. I guess the saddest thought was that I wouldn’t be around to watch you grow up, and you are so very special to both of us that that thought was the first to come to my mind, not my own body.”

In many ways, reading the notebook was frustrating. I kept returning to it again and again, searching for clues that simply weren’t there. This is perhaps reflected in a recurring dream I have: I am face-to-face with my mom. She is alive, wearing the long blue dress I picked out for her burial, but she doesn’t look like she did in her final days lying in bed at my childhood home. She is smiling, her hair thick and curly. She’s relaxed as she approaches me, as if we’ve never spent a day apart. And yet, as she draws nearer and begins to speak, I realize that I have nothing to say. I always awake with the same uneasy thought: I have no idea what I would tell my mother if I had the opportunity.

I now realize that I’ll never know for certain if Mom would have made peace with my decision not to attend Rice. I’ll always wonder if we’d be the kind of mother-daughter pair that call each other every day or if we’d rarely speak at all. And I still don’t know if she was quite as extraordinary as everyone claims—we have a tendency to canonize those who die young, after all.

It’s been more than five years since that frigid night I first opened the notebook, nineteen years since her death, and her words still gut me when I read them. Sometimes I’ll sit with a glass of wine (though not boxed white, as she preferred) and tear through the whole thing in one sitting, just as greedily as I did the first time. More often I will open to a random page, dropping in on a particular moment in our life together. No matter how I consume it, I always feel the same vulnerability, the same aching sense of loss. Yet I keep coming back because the most profound thing about the notebook turned out to be the simplest: its existence offers comfort, its creation a tangible reminder of my mother’s love.

Of course, losing her hasn’t gotten any easier. Many times over the years people have noted my ease—bordering on stoicism—in talking about my mother’s death. They praise me for my strength and bravery. But it isn’t toughness they see. It’s self-preservation. I have forced myself to accept her absence as normal.

Reminders that it isn’t normal do come, though. Birthdays or anniversaries or Mother’s Day are triggers, but ostensibly ordinary things are too. A certain bend in the path of the Window Trail at Big Bend National Park, the chorus of “Yellow Submarine,” the smell of sunscreen on hot skin—these all force me to reckon with the fact that most people my age still have their mothers, but I’ll never have mine again; that she was once here, with me, and now she’s gone.

Yet the notebook is also a reminder of all that she gave me before departing. There’s a certain passage I’ve been drawn to recently. It’s nothing dramatic. She’s explaining, as she does many times throughout the letters, why it’s been a while since she’s written. Often the reasons for this are expected—she was caring for a newborn (me), she’d had an extended hospital stay. But this one was different. “When you put together the dates on these very infrequent ‘tomes,’ ” she wrote, “I hope you’ll forgive my lapses in writing. I have so much to say to you, and want you to know how I feel about so many things, that if I were to convey it all, I’d be so busy writing I’d never have time for you!”

For once, I was glad that she decided to put down her pen.