A few minutes after two-thirty on the morning of November 18, the bottom stack of the Texas A&M bonfire began to groan and creak like a door opening in a horror movie. The 18-foot logs, which were wired together so that they stood perpendicular to the ground around the base of a towering center pole, started to lean slowly to the southeast. Above this base rose three more perpendicular stacks, stair-stepped to make the entire 59-foot structure resemble a wedding cake. Each tier rested on the one below it, so that when the bottom layer shifted, the entire stack of logs, more than a million pounds of timber, was set in motion.

At that moment, Thomas Kilgore couldn’t believe his eyes. One of the student leaders of the bonfire project, he was walking around the perimeter of the bottom stack, carrying out his assigned task of making sure that everything was going according to plan, when he thought he saw some logs move away from him. Thinking that his eyes were playing tricks on him — he felt weary, hungry, and a little faint — he shook his head to clear it and took a few steps back to get a better view. That retreat may have saved his life.

Brittny Allison was sitting on a plank some thirty feet in the air, suspended by ropes from the center pole as she wired incoming logs to those already in position in the second tier, when she saw the timbers in front of her start to move. She looked up, saw the third and fourth stacks bulge, and knew that they were going to fall. Her first instinct was to jump, but instantly she recognized that to do so would only propel her into their path, so she chose to ride it out in her swing. A log landed on her left shoulder, leaving a bruise on her biceps, bounced up into her face, and hit her nose. “I remembered to give with it,” she later said in her witness statement, “because I didn’t want my face to get injured.” The next thing she knew, the stack had finished falling, most of it away from her position, and she found herself on the shapeless heap that less than ten seconds before had been the bonfire, her swing nowhere in sight. Her left foot was trapped between two logs, but she was able to maneuver it free and climb down.

Collin Zacek was one of twelve Corps of Cadets members toting a huge log to the south side of the stack, the area that would suffer the brunt of the collapse. He heard a loud pop, which was the center pole fracturing, and saw it all happen in front of him, maybe ten yards away: A few more paces, a few seconds difference, and they all might have been dead. “I saw people jumping and trying to get away,” his statement read. “I saw some crushed to death in less than a second. We all froze in shock, as if we had turned to stone. The log we were carrying fell to the ground.”

Lucas Gregory was working on a second stack swing when he felt the stack move. He ducked his head, grabbed the two logs in front of him, and prayed. Instead of falling off the stack, the logs toppled over onto what was left of it. “After I realized that the stack had quit moving and I was not dead, I tried to get up,” he recalled in his statement. But he was pinned to the pile by a guy rope that had snapped and fallen into the collapsing logs. Rescuers cut him loose.

Jeremy Worley, standing on the second tier, heard a loud crack and saw the stack start to shift underneath him. “It happened so quickly, yet at the same time, it almost seemed like slow motion,” his statement read. He tumbled 34 feet to the ground and knew that he had to get away as fast as possible before a log crushed him. But when he scrambled to his feet, he did not know which way to run: The air was choked with dust, and most of the lights on the perimeter of the bonfire site had gone out. Through the dust cloud he spotted a lone light that was still working and sprinted for it. Only when he was safely out of harm’s way did he feel pain in one of his legs, which was so intense that he had to lie down.

Erica Alcala was on the ground on the southeast side of the stack, cutting wires into the right lengths for tying logs to the stack, when she heard the loud pop of the center pole. Above her, atop the first tier, a co-worker yelled for her to get out of the way. She looked up, saw the stack falling in her direction, and ran for her life. But Michael Ebanks, whose warning had saved her, was squarely in the path of the cascading logs and perished. The avalanche of timber would claim eleven other young lives.

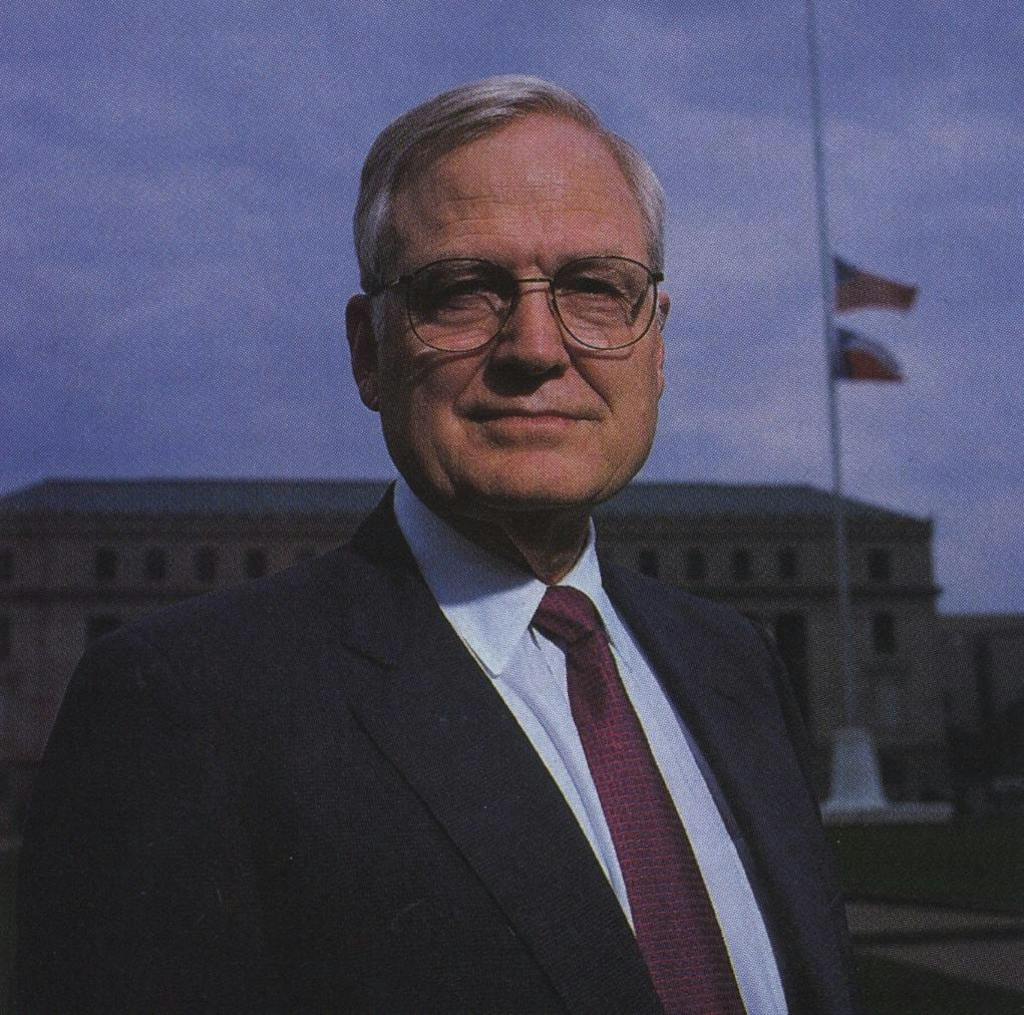

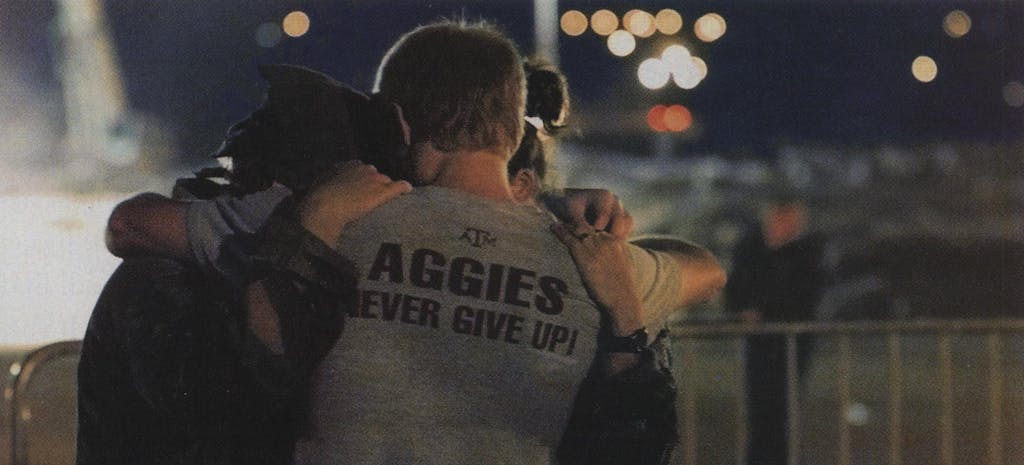

In the days after the bonfire’s collapse, the university turned its best face to the world — its unity, its dignity, its expressions of grief — but as the months have passed, shock and empathy have been followed by some hard questions: What went wrong? What happens next? Such is the rhythm of all public tragedies, whether it is the fall of a bonfire or the fall of an airplane. We have to know what happened so that the living can go on with their lives with some assurance that it will not happen again. The official judgment about what caused the bonfire tragedy will be rendered in May by an independent commission created by the university and chaired by Leo Linbeck, Jr., the head of a Houston construction company, who chose its members. Then the question of whether Texas A&M will have another bonfire this fall — or ever — and, if so, how it should be designed, built, managed, and inspected, will rest with A&M president Ray Bowen. At any other university, this process would be routine. At Texas A&M, it is charged with emotion. A correspondent who identified himself underneath his name as “An Aggie Dad” wrote the university, “[I]t is not the Aggie spirit to accept defeat. We do not wish to have these fine Aggies who have given their lives to have died in vain. AGGIE BONFIRE MUST CONTINUE AND DAMN THE TORPEDOES. . . . there must be a continuation of Aggie Bonfires, even if it doesn’t seem wise.”

Not all Aggies hold such extreme sentiments, of course. But enough do that the issue of what will happen to Bonfire (always capitalized in Aggie usage and seldom accompanied by “the”) is reminiscent of other crises in the university’s history, when hard-line traditionalists among both alumni and students resisted such changes as the end of compulsory membership in the Corps of Cadets and the admission of women. And make no mistake, this is a crisis, because if A&M does not take steps to ensure the safety of its students — to make certain that no other Aggies ever have to face what confronted Brittny Allison and Lucas Gregory and those who did not survive to make witness statements — then the empathy the university received from the world will turn to outrage.

How can a stack of wood be so important? As everyone knows, Aggies are different. To them, A&M means not just a university but a “fantastic, heart-warming, impossible-to-describe family,” as a graduate wrote in a letter published in the Bonfire memorial issue of the school’s alumni magazine. That family is defined and united by a unique culture rooted in the university’s history as a military and agricultural institution. Even today, when fewer than 2,000 of A&M’s 43,000 students are members of the corps, military esprit and conformity run deep, as do the idealized elements of small-town life: community, tradition, loyalty, optimism, and unabashed sentimentality. The continuity of this culture has been undisturbed by the admission of women and the increase in enrollment from around 10,000 students in the sixties to more than 40,000 — and a main reason, Aggies will tell you, is Bonfire, an immense three-months-long project that introduces freshmen to the Aggie way of preserving traditions and bonding in common cause. Never mind that it destroys thousands of trees every year, inflicts dozens of serious injuries, occupies upward of 100,000 man-hours, puts some students in academic jeopardy, and calls for two six-hour nighttime shifts in addition to daytime work during Push, the last two weeks of construction. Isolated, overlooked, and made sport of for much of their school’s 124-year history, Aggies long ago stopped caring whether the outside world appreciated or approved of their ways. “From the outside you can’t understand it. From the inside you can’t explain it” goes a popular saying on campus.

But now A&M has something it must explain, and the questions will not be easy to answer. Unlike an airplane crash, the bonfire had no black box. It did not even have a blueprint. Nor did it have professional supervision. It was a product of craft rather than science, a towering but primitive totem built according to methods that were passed on by word of mouth from one year’s group of artisans (student leaders known as redpots, a reference to the color of their hard hats) to the next. In hindsight, the more that is known about the history of the bonfire, the way it is built, and the mythology that surrounds it, the less the collapse seems like a freak accident and the more it seems like an accident waiting to happen.

Two dozen or so unsharpened yellow pencils rest in Teddy Hirsch’s right hand. The pencils represent bonfire logs. He taps the blunt lead ends against the desk in his home office to shape them into a cylinder, stands them straight up, and opens his fist. Thwack! Pencils fall in all directions. “When you stand logs vertically,” says the emeritus professor of civil engineering at Texas A&M, “you’ve got no stability.” He reaches for two small rubber bands and places them around the top and the bottom of the cylinder. This time the stack wobbles and tips over. He repeats the experiment, only this time he double-wraps the two rubber bands. The pencils stand. What’s the difference? “Friction,” says Hirsch. “With enough friction you can resist horizontal shear.”

Teddy Hirsch, class of ’52, is a lifelong Aggie. Now seventy, he has spent almost his entire professional career at Texas A&M, earning three degrees, including a doctorate, in civil engineering and serving on the faculty from 1956 to 1992. For 25 years he was the head of the structural engineering division. The next time you drive on a freeway and see a collision barricade made of 55-gallon oil drums, think of Teddy Hirsch: It was his idea. Tall, trim, and with the weathered face of a man who has spent a lot of time on job sites, he now works as a consultant in a room filled with engineering tools, references, and Aggie memorabilia. Ever since he moved into his house a few blocks south of campus in 1966, he has gone out to the woods where bonfire logs are cut to gather his winter firewood from the leavings. “I’m going to tell you what I tell prospective clients before they hire me,” he had said when I first called him. “I don’t give opinions, just facts. You may not like ’em, but they’re facts. And the fact is that the layered wedding cake is inherently unstable.”

Hirsch is no second-guesser. He became worried about the stability of the layered wedding cake years ago, when he noticed a pattern of bonfires’ collapsing soon after being lit at eight o’clock on the night before the annual football game with the University of Texas, or as Aggies call it, t.u. “We have a saying that if Bonfire stands until midnight, we’ll beat t.u.,” he says. “But every layered wedding cake, to my memory, collapsed before yell practice was over. It stood for only about thirty to forty-five minutes.” He aired his concerns inside the civil engineering department and conveyed them to an administrative office that oversees Bonfire. But university officials rarely interfere with student leaders unless rules are broken or assistance is sought. After the center pole bent 90 degrees during a prolonged 1994 rainstorm, pushing part of the stack over with it — no students were working on Bonfire at the time — Hirsch set up a meeting with a group of redpots to talk about safety. “I could tell they weren’t interested at all,” he says. “I was just another professor trying to lecture them. When I finished talking, they didn’t ask any questions, they just got up and left.

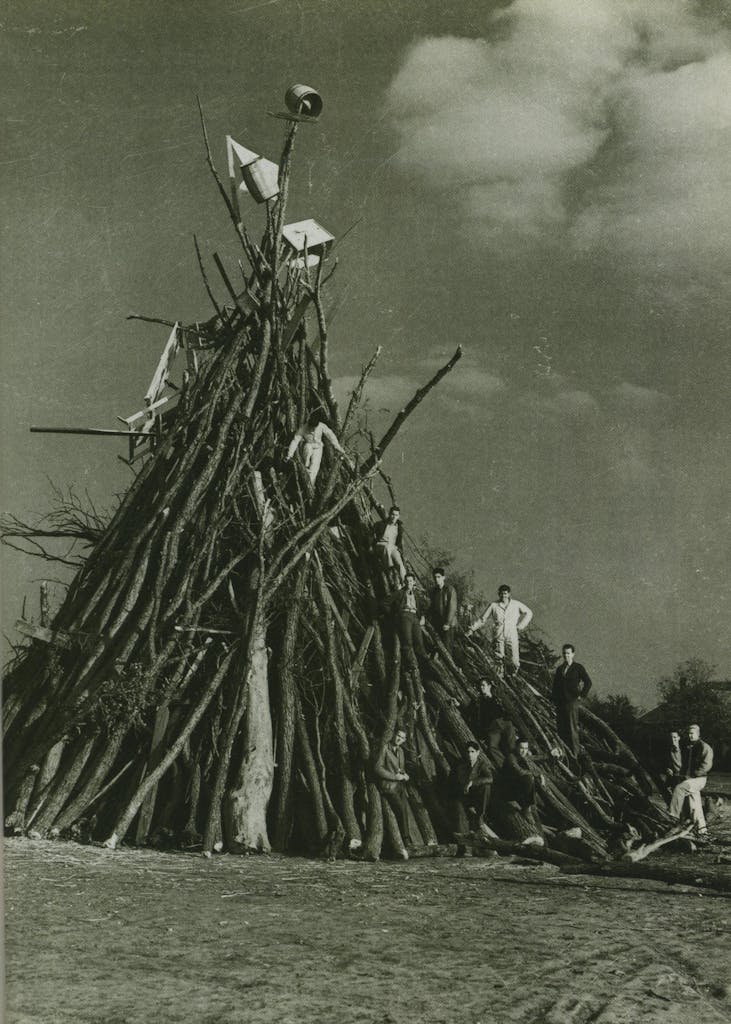

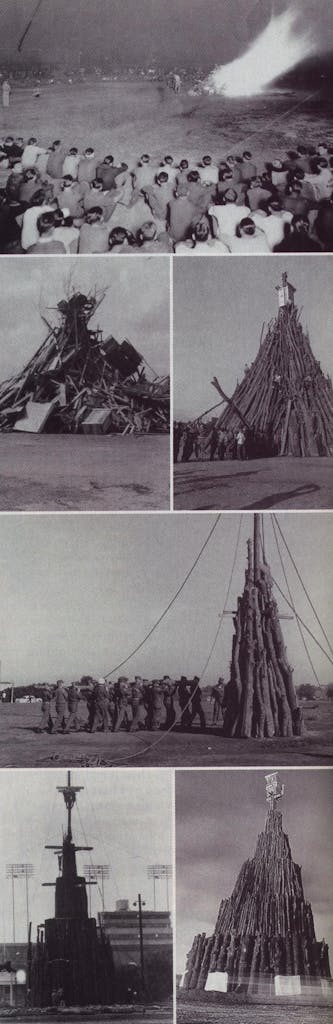

“You hear people say, ‘We’ve been building Bonfire for ninety years, and this is the first catastrophe.’ Well, it’s not so. This design is only twenty years old, and the center pole has fallen twice in six years.” He walked over to a couch and grabbed a sheaf of papers. From university archives and old yearbooks, he has assembled a series of photographs and charts portraying the evolution of Bonfire. In the beginning, he says, Bonfire was nothing more than a pile of lumber and trash. This changed radically in 1945, the first year that Bonfire was made entirely of logs placed around a center pole. It resembled a tepee. The Aggies soon learned that they could extend the sides of the tepee to a great height by splicing the center pole and using a pulley to haul up additional logs. Bonfire reached a record 105 feet in 1969, when administrators, concerned about a fire hazard from sparks flying so high in the air, stepped in to impose a 55-foot limit.

Hirsch flips through his photographs. “Look at how the logs are leaning inward,” he says, pointing to one of the tepee photos. “They’re always at an angle of between 23 and 30 degrees. This design has tremendous vertical and horizontal resistance. When logs are pushed together and lean against each other, horizontal shear can be resisted.” He flips again, this time to the 1984 Bonfire. The layered wedding-cake design has replaced the tepee. “Now the slope of the logs is 14 degrees,” he says. The last photograph shows the ill-fated 1999 Bonfire, just a day and a half before the collapse. The logs look as vertical as fence posts. “Look at the angles of the four stacks,” says Hirsch. “Zero degrees for the first stack, 4.4 for the second, zero, and zero. All that is holding the whole thing up is the center pole. It couldn’t do it.”

Just because a structure is unstable doesn’t necessarily mean that it will collapse; even a house of cards can stand under ideal conditions. Inside the bonfire stack, the center pole and the wiring of logs to the center pole and to each other provide enough strength to overcome the static force of the weight of the logs. The problem occurs when a dynamic force develops in the stack. When a million pounds of timber starts to move, the wire ties snap as if they were made of string, and the center pole must contend with forces far beyond its ability to withstand. Not even Teddy Hirsch can identify what caused the stack to reach its breaking point. But documents that A&M has released for examination by the Special Commission on the 1999 Bonfire and by the public, including the students’ witness statements, indicate several possible problems that could have contributed to the collapse, all of which remain speculative:

•The ground sloped. The area on which Bonfire was built dropped one to two feet toward the southeast — the direction in which the stack fell. This by itself wouldn’t been enough to cause the catastrophe, unless . . .

•The stack was overloaded on the uphill side. Several witness statements included this observation. Witnesses reported that only one of the two cranes that brought logs to the stack had been working the previous night, and it was located on the uphill (west) side. Students standing on top of the tiers noted that the extra logs on the west side left less room for walking than was available on the opposite side. An uneven distribution of logs could explain reports on the eve of the collapse suggesting that the stack appeared to be leaning toward the downhill side.

•The stack was top-heavy. The partially completed structure had already exceeded the university’s 55-foot height limit by 4 feet, with two more tiers and 16 feet left to go. Logs were still being added to the bottom tier when the whole thing fell. The second, third, and fourth levels were already well developed. Was the bottom tier capable of sustaining that much weight?

•The stack was “loose.” One witness who had worked on previous Bonfires noticed that when she walked on top of a tier, her feet kept getting caught in spaces between the logs. A horticulture major, she believed that the logs were more curved than usual, making it hard to pack them in tight. A looser stack means less friction.

•The center pole was flawed. A day before the collapse, a crane hit a crosstie — a piece of lumber that was nailed to the pole to help guide logs — and sent a jolt through the stack that was noticeable to students. The incident may have inflicted damage to the pole.

On the afternoon before the collapse, a surveying class reported that the pole seemed to be leaning to the southeast. By manipulating two sets of four guy ropes, Bonfire workers tried to straighten it. But the force of the logs on the pole was so great, Teddy Hirsch has concluded from an examination of the pole, that instead of correcting the original bend, the students only succeeded in creating a second bend in the opposite direction, higher up the pole. That night, a few hours before the end, workers removed the lower set of guy ropes, which were interfering with the addition of logs to the stack — a normal decision made at the normal time in the construction process, and in a normal year it would have had no effect. But on this night it may have deprived the center pole of much-needed support.

During the first part of the midnight shift, nothing unusual occurred. Just before the collapse, a crane delivered a large log to the first tier — a process known as “slamming.” Was this the trigger? Compared with the mass of the stack, the log was barely more than a twig — but something had to start the logs in motion. Or did the addition of one more log at the wrong place overload the center pole? Suddenly, the pole bent sharply to the southeast. Still hemmed in by logs on all sides, it snapped in three places — at ground level, just above the first stack, and near the top. The west guy rope also snapped near its connection to the center pole. Whether this caused the pole to break or was a result of the pole failing is still unknown. The fractured pole released its energy into the stack, disrupting it from within. The bottom tier fell toward the downhill side, the second tier wedged into it, and the upper levels dropped down into the chaos.

The death of twelve students in a university activity would be a terrible blow to any school, but at Texas A&M the pain was even more acute because the bonfire’s collapse tests one of the core beliefs about what A&M’s mission should be. Known as “the other education,” it holds that students learn as much from participating in activities as they do in the classroom, and specifically what they learn is leadership. This philosophy originated with the school’s third president, Lawrence Sullivan Ross, who wanted the military side of student life emphasized above the academic side. In recent years, as A&M has become a flagship academic institution, “the other education” — a term that was coined in the seventies — has come to mean that an essential part of being an Aggie is to join campus service organizations, to create your own organization if you wish, to participate in traditional activities like Bonfire, and to develop an ability to lead. So strong is this culture that those who don’t buy in, especially to A&M’s fabled traditions, have long been dismissed as “two-percenters” (designating how tiny the minority of dissidents is) or, more recently, “skim” (less widely used, referring to those who are only interested in academics and hence are just skimming the surface of being an Aggie). Central to the idea of the other education is the need for students to be truly in charge. Thus, the absence of professional oversight of Bonfire — by, say, a structural engineer — occurred not by neglect but by design, with the best of intentions but with the worst of results.

Student body president Will Hurd, 22, is an example of why the other education means so much at Texas A&M. “It got me here,” he says. “I was planning to go to Stanford. I wanted to go there, and I had a lot of financial aid. Then my high school counselor in San Antonio said I should apply to A&M. I came up here and saw the opportunities to develop as a whole person.” Very lean, with a long, narrow face, Hurd is an imposing figure in his black slacks, white dress shirt, solid yellow tie, boots, and suspenders. Just the way he sits in a chair communicates gravitas; he seems to be propping up its back instead of the other way around. A placard in his windowless office reads “People don’t come to A&M to become Aggies . . . They come to perfect the Aggie that is already within them.”

Hurd, who is majoring in computer science and minoring in international studies, talks about having studied in Mexico City, interned for a microchip manufacturing company in Manila, and served as a counselor at an A&M leadership program in Italy for thirty incoming freshmen. Because A&M gives students so much responsibility, he says, he had the opportunity to manage a $5.6 million budget as head of the Memorial Student Center and, in his current office, to be what he calls “the mayor of a moderate-sized town.” He is also media-savvy, perhaps as a result of the recent tragedy; he answers questions about Bonfire in an effortless manner but with careful words. When I asked him whether the idea of the other education — delegating nearly all authority and decision making to students — was compatible with safety in such a technical and high-risk activity as Bonfire, he said, “To say that the students in charge of Bonfire weren’t experienced enough is not accurate. Just because these were students doesn’t mean it was unsafe. I think documentation and planning need to be improved, and the selection of leadership needs to be based on an understanding of technical details as well as a person’s ability to manage a group of people.” At first I thought that he was advocating change, at least in the way that redpots are chosen — currently, each group of redpots chooses its successors — but then I realized the international studies student had given a diplomat’s response that was totally, brilliantly, ambiguous. “How should it be done?” I asked. “We’ll see, after the commission has completed its report,” said Will Hurd. “To be continued.”

The purpose of bonfire, wrote a redpot back in 1992, “is to promote and maintain the Aggie Spirit among students and former students . . . and to symbolize the burning desire of all Aggies to beat the hell outta t.u.” Over the years, the second function has become subordinated to the first. There are a lot of things to dislike about Bonfire: It is dangerous, harmful to academic standing, rife with drinking and hazing, and prone to occasional public displays of racism and other forms of inexcusable behavior. The night that it burns is the biggest party night of the year in College Station, not just for students but for residents and even high school kids. Bonfire has become a tourist attraction, bringing former students and their families back to the campus by the thousands; attendance estimates in recent years range up to 70,000. Think of Bonfire as the Aggie Mardi Gras: part hard work and preparation, part celebration, part public drunk. Like Mardi Gras, Bonfire originated in beliefs that Aggies hold sacred; like Mardi Gras, the sacred has often been overwhelmed by the profane. And yet, it is hard to imagine A&M without it.

Bonfire gets fish — campus nomenclature for “freshmen” — involved in becoming Aggies. Very involved. Participation is voluntary, but because students always work with those who live in their residence hall, the peer pressure to join in is substantial. Fish show their spirit by volunteering to become “letterheads”: They shave their heads to display a letter of the alphabet, and together they spell out a message such as “Aston [Hall] Fighting Texas Aggies.” The tradition is a metaphor for the Aggie family: Separately the letterheads have no meaning, only together. Each hall has its own traditions — in Hart, the letterhead with the “R” shaves it backward — and a distinctive decor for its pots. To stimulate enthusiasm, special recognition goes to fish who are exceptionally “red-ass” — a term of honor at A&M that means gung-ho Aggie.

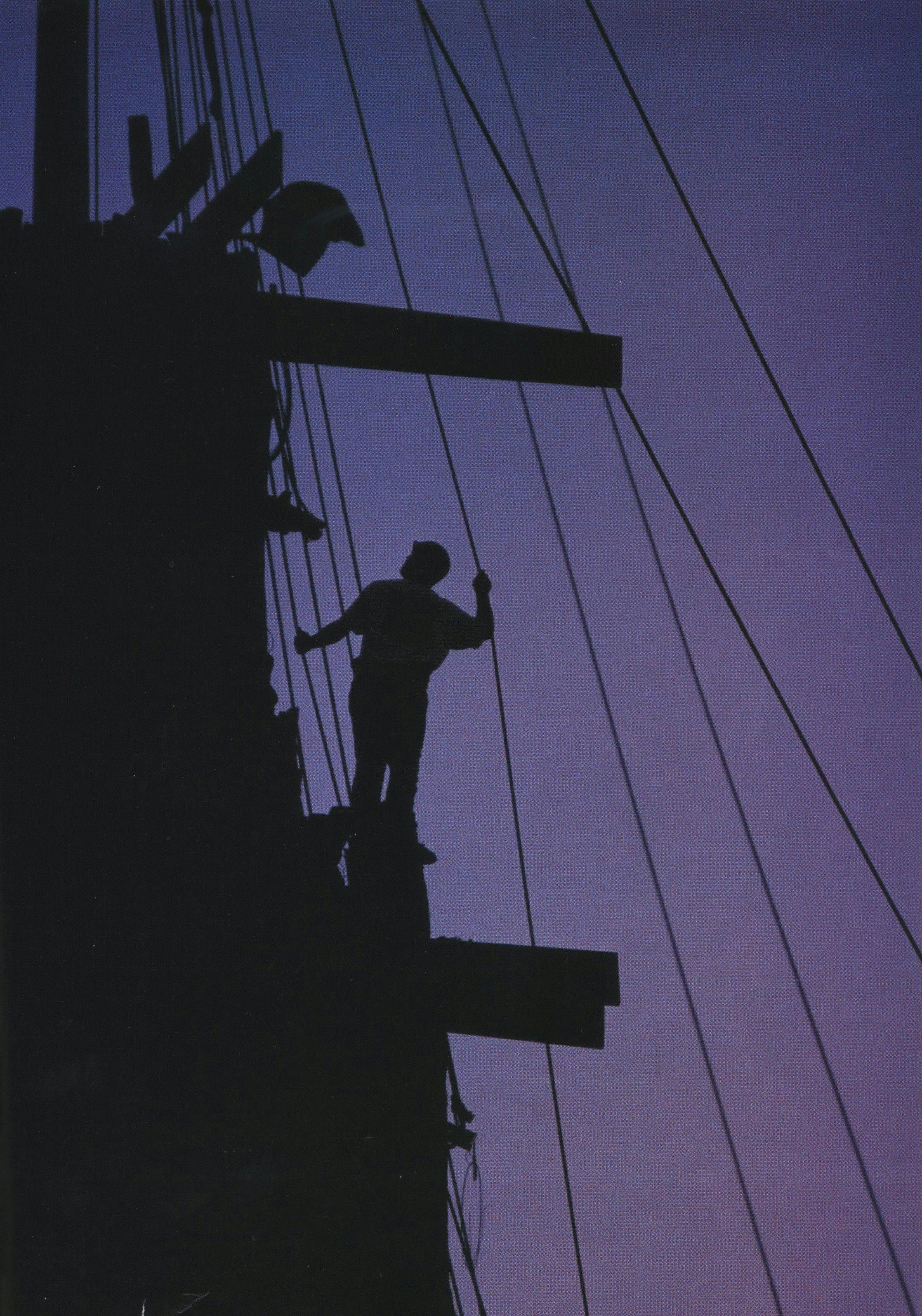

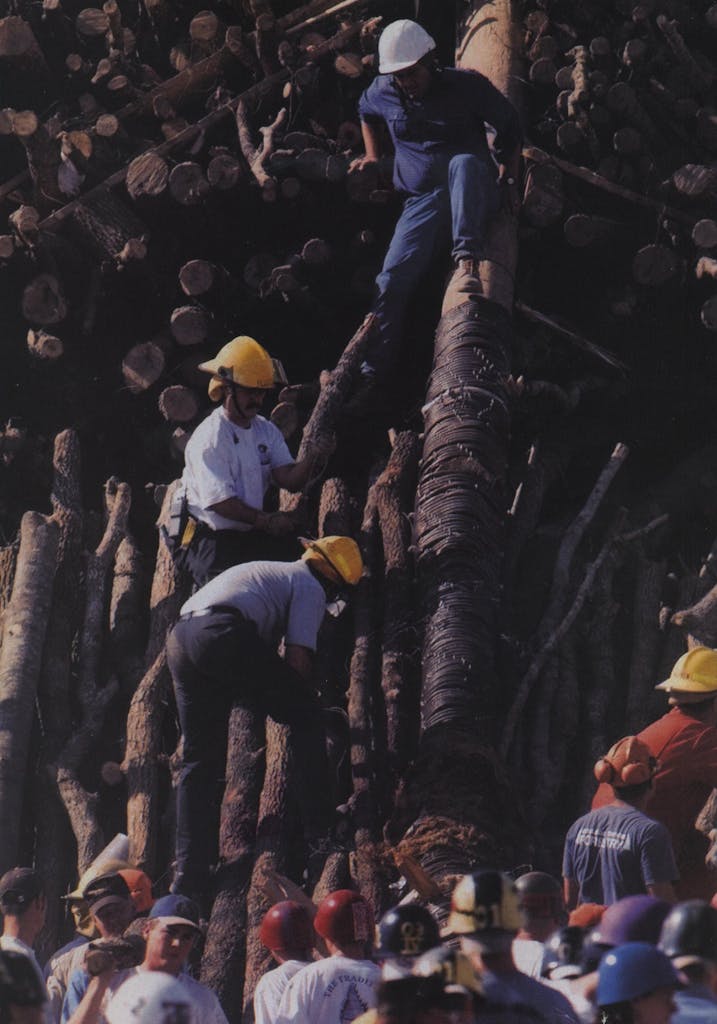

The breadth of participation is astonishing; Aggies say Bonfire is the largest student-organized project in the nation. Total participation is around five thousand students. Two thousand of them turned out this year for the first day of harvesting logs. Cut, as it is called, takes place on weekends, usually on rural land whose owner has donated the trees for the bonfire. It goes on for almost two months and involves the use of chainsaws and axes to fell trees, machetes to clear brush, and tractors and large trucks for heavy-duty work. Once the center pole is in place, construction begins. At one time fish were not allowed to work on the stack, but today they form the backbone of the workforce; most upperclassmen live off-campus, away from the Bonfire frenzy. If freshmen didn’t work on Bonfire, one witness observed, it wouldn’t get built. By the night the stack is burned, the fish have been molded into Aggies. No other campus activity can fill that role. That is why Bonfire is so important — not just to students but also to older Aggies. It preserves the A&M they remember.

That is the sacred part; here is the profane. Until this year, cutting has been regarded as far more dangerous than the actual construction of Bonfire. Two ambulances are on hand at the cut site, and for good reason. Lacerations are common. So are injuries to hands and feet during the backbreaking work of hauling logs. A&M keeps track of injuries by the week with a form that includes such categories as “Amputation” and “Trauma-Blunt.” In 1993 the injury total hit 79; in 1998 it was down to 37. Still, the official description of injuries is sobering: “foot cut with ax,” “shin cut with machete,” “smashed right index finger,” “fractured vertebra” (incurred during “groding,” or horseplay, involving other members of the student’s residence hall). In 1996 a pickup truck taking ten Aggies back to campus from the cut site, eight of them in the bed, flipped over after the driver lost control. One student was killed, and it could have been much worse.

Injuries aren’t the only problem at the cut site; located many miles from campus, it is an opportunity for making mischief. In 1997 one of the residence halls smuggled in a stripper. One year the landowner repeatedly brought beer to the cut site. Beer and chainsaws don’t mix. After a hazing incident in 1998, the Student Organization Hearing Board imposed sanctions on the Texas Aggie Bonfire organization, including a requirement that a statement addressing hazing be delivered each morning at the cut site before anyone can work. The futility of this remedy did not escape the sanctioners: “The Board recognizes that this task will require some thought and effort in order to ensure that the daily announcement does not turn into a joke.”

Nor has the stack site been free of incidents. In 1996 no fewer than three Aggies fell off the stack at different times. One hit four levels on his way to the ground, suffering head and internal injuries; the toll of the other two victims included a concussion, a broken foot, and a broken wrist. In 1998, campus police found a keg of beer in a shed near the stack. They also found an intoxicated student unconscious and vomiting — a life-threatening situation — who was not being tended to by anyone. That same year, the A&M administration received a letter from a graduate who came to town to watch Bonfire burn. He was appalled to see a member of the Corps of Cadets sporting this slogan on his helmet: “If I knew niggers were this much trouble, I’d have picked my own God damn cotton.”

The problem with Bonfire is that it is red-ass (sometimes abbreviated as RA) culture run amok. The administration has never known quite what to do about it; it needs RA Aggies to uphold the school’s uniqueness and guard its traditions, but it doesn’t need drinking, hazing, racism, and strippers, and it has never figured out how to get one without the other. The redpot traditions exemplify RA culture. One is that no woman may set foot in a certain area of the stack site unless she has slept with a redpot; an Aggie who described herself as weighing 95 pounds wrote a letter to the student newspaper two years ago protesting that a redpot had shoved her when she breached the boundary to avoid a mud puddle. A wide-ranging witness statement given by a female member of the corps told how each group of redpots fills a jar with ejaculate and sets it atop the stack to burn. “The other education,” which works so well in service areas like student government, doesn’t always work so well with redpots. In 1993 a redpot was cited for bringing 53 beers to the stack site after midnight. Redpots had to know about the keg that the police found in 1996; their job is to know everything. Redpots knew that a stripper was going to be smuggled into the cut site in 1997 and didn’t stop it. Redpots exceeded the height limit for the 1999 Bonfire. This is not the leadership that the other education has in mind.

The result of the RA attitude is that, while almost every Aggie loves the hoopla of Bonfire night, many Aggies do not want to be involved with the building of Bonfire. In the late eighties objections to the slaughter of trees led to the formation of an organization called Aggies Against Bonfire. But at A&M, any organization whose name begins with “Aggies Against” is unlikely to succeed. A&M is a positive island in a cynical sea; students put signs in their dorm windows touting their organizations (“Pro Bonfire”). In the best A&M fashion, Aggies Against Bonfire disappeared, to be replaced by Aggie Replant, an organization that plants trees in the spring to make up for those that were cut down in the fall. The RAs know that their support is dwindling. “I’ve seen lots of negative attitudes across campus,” a Bonfire crew chief said in an interview for academic project in 1998, “and sensed the feeling from both students and administration that people do not appreciate Bonfire. Every year there are fewer and fewer Pro Bonfire signs. That bothers me. Bonfire is Aggieland.”

My heart wants to have a bonfire,” Ray Bowen says. “My brain gives me the problem.” An Aggie-educated engineer, class of ’58, Bowen understands all too well what happens when dynamic forces disrupt a million-pound stack of wood. Now, as A&M’s president, he is waiting for the Linbeck commission to weigh in before he decides the future of Bonfire. “You’ll be able to track the decisions we make against that report,” he says. But he has already made up his mind about one thing: If there is to be a bonfire, it will be a student-run event. “We thought about building Bonfire with professionals,” he says. “We concluded that students wouldn’t come out to watch it. This set of students feels an obligation to keep the tradition going. If they are totally disconnected from it, then all that’s left is a stack of wood.”So the question is, can Bonfire be made safe and still allow A&M to remain true to its culture? It can certainly be made safe — smaller, for example, and built according to a different design, this time one that is written down and subject to quality assurance by a faculty structural engineer. A 45-foot tepee-style bonfire, for example, would be stable; it would also require half the volume of wood used in the present wedding-cake design and would reduce a lot of the problems associated with Bonfire: too many trees cut down, too many injuries incurred while cutting down those trees, too much time spent working on Bonfire to the detriment of classwork. But at what point do these changes mean that the cultural benefits of Bonfire, the prolonged bonding of so many new members of the Aggie family, cease to exist? This is A&M’s dilemma.

And this too is A&M’s dilemma: How to honor the dead? This is no small issue at a university with a strong military tradition. The overwhelming belief on campus is that to cut back or abandon Bonfire is to commit the ultimate negative act — to surrender to death. There is a tendency to treat the victims of the tragedy as martyrs to a cause. The last thing that the dead Bonfire workers would have wanted, many members of the Aggie community have said (including some relatives of the deceased), is for their deaths to damage the tradition of Bonfire. But if the lessons of the collapse go unheeded, and some day another Bonfire tragedy occurs, then surely the fallen Aggies of November 18, 1999, really will have died in vain.