Tim O’Brien, the author of the celebrated short story collection The Things They Carried, is, by his own admission, a “preposterously slow” writer. But the longtime Texas State University professor’s latest work, Dad’s Maybe Book, published in October 2019, is the sort of project that takes a decade and a half to write.

O’Brien was born and raised in southern Minnesota. In 1968, as a student at Macalester College, he was drafted and sent to Vietnam. His experiences as a soldier often inform his stories and novels, including Going After Cacciato, which won the National Book Award for fiction. After returning from war, O’Brien attended Harvard University. He’s lived in Austin, with his wife, Meredith, for twenty years and currently teaches creative writing at Texas State. (Full disclosure: I am currently a student in TSU’s MFA program and have taken a class with O’Brien.)

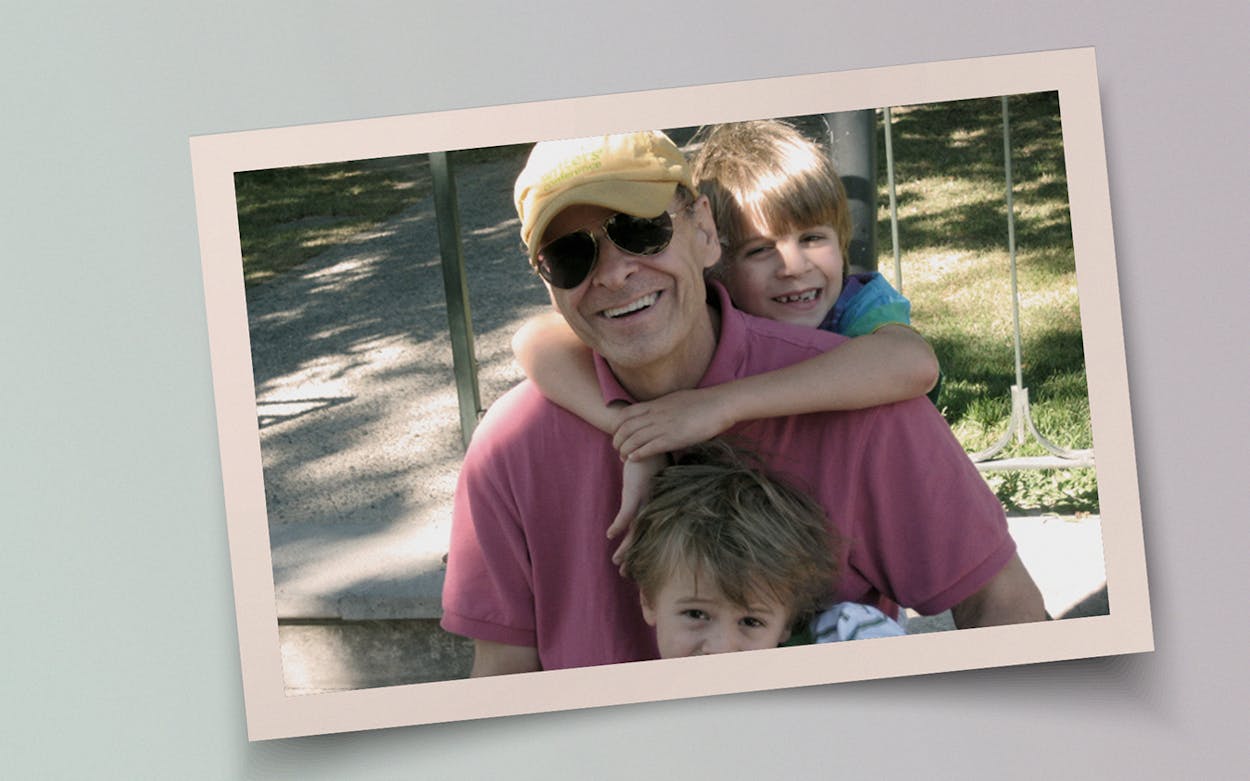

In 2003, at age 58, Tim O’Brien became a father. After the birth of his first son, Timmy, O’Brien began writing down his memories of his son’s early years. But his second son, Tad, born in 2005, gave O’Brien the idea of putting those letters together in a book. His family continued to call it a “maybe book,” and the title stuck. All books, as O’Brien writes, are maybe books at the beginning. .

The result isn’t a sage’s armchair memoir. O’Brien, now 73, grapples openly with his own mortality and the lessons he wants to teach his sons, even after he’s gone. Now on the other side of his decision to become a father, O’Brien writes to his first son: “I would trade every syllable of my life’s work for an extra five or ten years with you.” For anyone who has ever loved a child, the book’s pages will blur through tears of recognition.

Texas Monthly recently sat down with O’Brien to talk about his book, writing about war, and that time he faked a Southern accent in the movie The Notebook.

Texas Monthly: Dad’s Maybe Book is tough to categorize. How would you describe it?

Tim O’Brien: It’s not a parenting book. It’s not a manual. I don’t have advice. It’s about, in part, fatherhood. Or, really, parenthood, because Meredith contributes to this. But it’s not advice. It’s about being human and loving people. In this case, children. And loving decency, kindness, and human generosity, and despising the reverse of those things. I despise when people are cruel, intolerant, and hypocritical.

TM: Do you think the book’s title makes it difficult to categorize?

TO: The title is misleading. But it’s my title. I fell in love with maybeness. It’s not that I don’t like the title. I like it. And yet, it causes problems. A lot of people haven’t read it because of the title. And that’s my doing. But I can say that, with Going After Cacciato, no one could pronounce Cacciato. But the book succeeded, and I’m hoping the same with this book, because I think it’s a serious literary book. I’m as proud of it as The Things They Carried. In some ways, more so.

TM: There are nine chapters in this book titled “Home School.” What inspired those sections?

TO: My kids go to school, and they get that kind of education. I try to teach them other stuff that they’re not being taught in school. Usually it has to do with the moral choices you’re going to face as you grow up. It’s not to impart information but to impart situations and say, “What would you do?” Almost all of the home school chapters have to do with choices you’re going to have to make in your life, some of which are really hard. It’s not that one thing is good and one is bad. It could be that there are two good things. And you can’t have both. You love John, and you love Jack. Who do you marry? Who do you say “yes” to?

TM: In one of the “Home School” chapters, you draw similarities between the Battle of Lexington and Concord, and Vietnam. And then you turn it into an actual war lesson for your sons.

TO: I warned the reader that this chapter is going to be detailed, and the devil lives in the details. And that’s what my kids had to go through. For seven days, I researched the battle and talked to my kids about it for about an hour a day. When you think of the battle of Lexington and Concord, you think of the shot heard round the world. But it was horrendous for the British. It was as bad as Hamburger Hill in Vietnam, which took its name from all the dead people. But it was worse than that. The same number of casualties, but the British suffered their casualties in less than twenty-four hours. The Americans suffered their casualties in Vietnam in ten days. And worse yet, in the Battle of Lexington and Concord they were using single-shot muskets. They had to reload. It took two minutes to reload, a minute if you were fast. In Vietnam, we had automatic weapons, artillery, and mortar rounds.

You wouldn’t believe how many British soldiers wrote about fatigue. How exhausted they were. They walked carrying a hundred pounds, twenty miles there and back. Forty miles in 24 hours. That’s not counting the running and ducking and charging. Just imagine how fatigued you’d be. Your body. Fatigue is a lesson I talk about with the kids. How it cripples your moral faculties. You’re so tired that you lose control. What would not normally be permissible suddenly is. “I’m exhausted, my friends are dying, so I’m going to kill, even innocent people.” Which is what the British did. And then I ask [my kids], is war glamorous?

TM: The book is structurally interesting. It skips around within the chapters.

TO: The structure came out of life. Structure, in this case, is a bad word. It’s the opposite. I tried to replicate the chaotic messiness of life. That’s why the chapters jump around. Not just in the content, but they jump around in time. Back to my dad, an alcoholic, when I was a little boy. To the porch of his San Antonio retirement home. Then back to childhood. Because that’s how my memory works. There is a single theme that runs throughout the book. It’s mortality. My own. But all of ours, really.

TM: I didn’t know until reading the book that you had acted in The Notebook. What was that experience like?

TO: It was freezing cold. We were in South Carolina, and we were wearing booties to keep our feet warm. We had these parkas they put on us. All day long, we sat there pretending it was summer. They didn’t film under the table, so we kept our boots on. It was the scene where Ryan Gosling comes to meet [Rachel McAdams’s] family at this outdoor picnic. I was this rich Southern guy, putting on this fake Southern accent. Nick [Cassavetes, the director] said, “talk like yourself.” O’Brien then puts on a thick Southern drawl. “Every young man should visit Europe. Builds character.” I’d say “charactuh.” Nick said, “talk like a human being.” We were drinking whiskey, only fake. But Cassavetes started putting the real thing in mine to make me act normal. But I wanted to act it up. I’d been practicing. It was really fun.

One of the funniest things that happened was, I’m sitting here at this table. Joan Allen’s at one end and the man, David Thornton, who played her husband sat at this end. They were the parents of Rachel McAdams’s character. He was just the sweetest guy. In between takes, my wife Meredith and I would just talk to him. He was so fun to talk to. So nice and normal and kind. At one point, he said he was married. Meredith asked, “Well, what does she do?” And he said, “She’s in a band.” And Meredith said, “Well what does she play?” He said, “She plays the tambourine.” So she says, “Does she do anything else?” “Yeah,” he says, “sometimes she’ll sing.” “Well, what’s her name?” my wife asks. “Cyndi Lauper.” He was so nice. He didn’t want to brag. She plays the tambourine . . . he was going to leave it there! Someday I’m going to write about that experience.

- More About:

- Books