Q: Last year I was attacked by a persistent and ornery mockingbird guarding her nest. It was a tricky situation because I was trying to protect a take-home plate of homemade enchiladas and borracho beans from some generous parents for teacher appreciation week. The good news is that after all my years of being a native Texan, I finally experienced an official rite of passage: being attacked by a mockingbird. Are there any other things you consider to be Texan rites of passage?

Rebekah Kern

, Austin

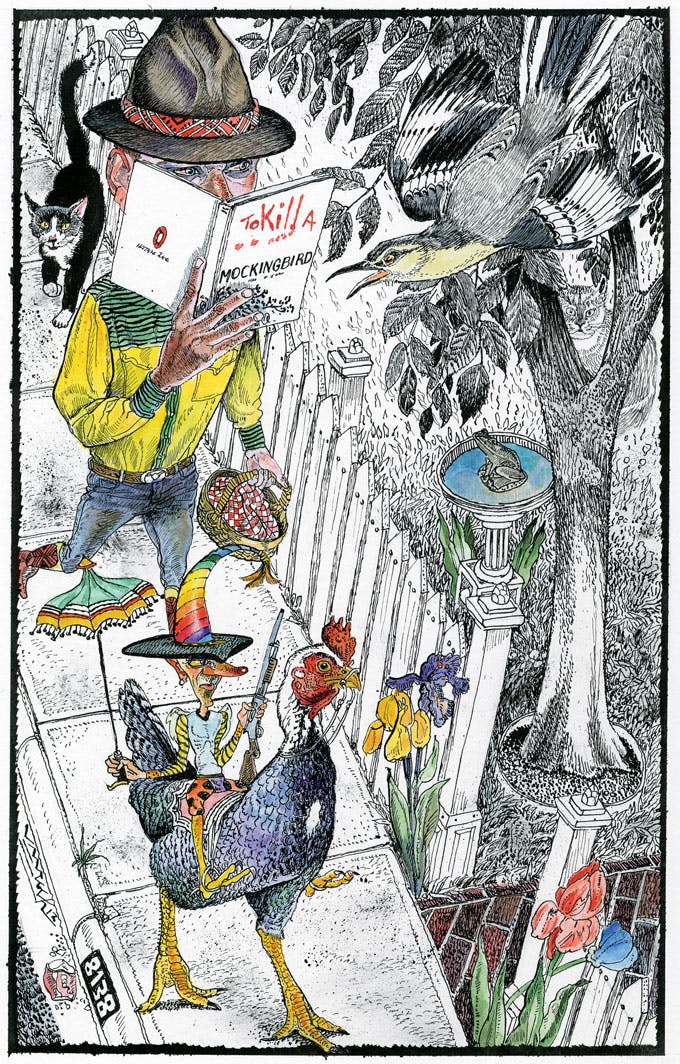

A: Getting dive-bombed by an unruly mockingbird is a fairly obscure Texan rite of passage, often overshadowed by more-celebrated rituals such as learning to ride a horse or eating one’s first corny dog at the state fair. Yet it is a sacred tradition nonetheless, and the Texanist is pleased you have brought it up. Roy Bedichek, in his book Adventures With a Texas Naturalist, described the encounter thusly: “Like a silver arrow from the bow of some high-stationed archer, down darted the mockingbird upon the incautious intruder.” Like it or not, most Texans will at one time or another know this harrowing experience firsthand—the chirpy song belying an imminent attack, the violent swoop of the fowl as it zeroes in, the cloudburst of pecks to the noggin. Nevertheless, there is something enriching about such an episode. To begin with, the mockingbird is, as of 1927, the official state bird, and any sort of physical encounter with our sanctioned heraldry is to be revered, if not enjoyed. (In choosing the mockingbird, the Fortieth Legislature applauded the creature for being “a fighter for the protection of his home, falling, if need be, in its defense, like any true Texan.”) Second, as those who study them have recently discovered, mockingbirds are capable of distinguishing between individual humans, meaning that you were chosen for some reason unique to yourself (probably the beans). As for similarly obscure and unpleasant Texan rites of passage, well, there is the requisite first in-the-face squirt of blood from the eye of a horny toad; the first fall into a stand of prickly pear; and the first time getting bucked off a goat, bull, horse, or sweetheart—all of which do their part to bring us into full Texanhood.

Q: Is there any rhyme or reason to the numbering system used to designate Texas’s great farm-to-market roads? Also, where is FM 1? What is the highest-numbered FM road, and where is it located?

Louis Dunham III

, Tomball

A: Start the clock: Sort of. In San Augustine and Sabine counties. Farm-to-Market 3549, in Rockwall County. Stop the clock and give the Texanist his prize, which he will share with his friend Penny at the Texas Department of Transportation, whom he called to get these answers. Penny also told the Texanist that the department keeps a list of all the roads in a “black book” and that when it’s time to name a new road, it just goes to the next number, although the locals sometimes have special requests, which are considered. And just in case you’re wondering if a person could drive to the moon if all the farm-to-market roads in the state were strung together, the answer is no. The 37,916 total centerline miles of our FM roadways would leave you about 200,000 miles short. Again, credit for that info goes to Penny, who also filled the Texanist in on what the deal is with ranch-to-market roads. The general but much-violated rule of thumb is that RMs belong west and FMs east of U.S. 281. What’s the shortest FM road? That would be Crosby County’s FM 122, which stretches for a mere .13 mile. And what’s the longest? FM 168 in the Panhandle, which will roll up nearly 140 miles on the odometer. The best for driving? The Texanist himself will field that one: 165 in the Hill Country, 170 in Big Bend, 139 in East Texas, and just about any one on which he finds himself on a pretty day with the windows rolled down.

Q: My son, who will start high school next year, plans to pursue lacrosse full-time, forgoing football altogether. He’ll be attending the same school where I was the starting quarterback for two years. Should I try to change his mind, or do I have to get on board the lacrosse train?

Name Withheld

A: All aboard! It seems the great Texas lacrosse revolution has no end in sight, although it remains unsanctioned by the University Interscholastic League, the organization that oversees interschool extracurricular athletic (as well as music and academic) competitions. Football, for now and probably evermore, still reigns. That said, your situation is unique, and the Texanist understands where you are coming from, having known some starting QBs himself. Still, he advises you not to intervene too strongly. It’s a proven fact that chips off the ol’ block are a naturally occurring phenomenon and cannot be manually sculpted. Your boy’s interest in the pigskin would be compelled, not natural, which would inevitably lead to an unsatisfactory 60 to 75 percent level of “giving”—far less, as you well know, than the required minimum of 110 percent.

Q: Last week, I was driving from Houston to Austin and stopped at a convenience store to get a spit cup, and they charged me fifteen cents for it. Fifteen cents! For an empty paper cup! Isn’t there something in the state constitution barring such a charge? And if there isn’t, shouldn’t there be? This is still Texas, isn’t it?

Name Withheld

A: The Texanist understands the enjoyment one gets from stuffing a big pinch of tobacco into one’s mouth while tooling along between point A and point B. He knows just as well the extreme panic of having a voluminous mouthful of tobacco juice with no good receptacle in which to expel it. The greedy, low-down scoundrel who would charge for a disposable makeshift paper spittoon is the same sort who charges for the likes of chips and salsa; sliced pickles, onions, or white bread; and tea or coffee refills. These items ought to be gratis. Maybe it is time to lobby the Legislature for a constitutional amendment making this clear once and for all. The Texanist, by the power vested in him, hereby appoints you to get this ball rolling.