On October 30, David Eckstrom put a Bob Dylan record up for auction on eBay. It didn’t appear much different than any other listing on the site. It wasn’t flashy, and it didn’t appear professionally done. Featured in the “people were also interested in” section was a different version of that same Dylan album for $20.

When the auction ended ten days later Eckstrom had received no offers, likely because he set the minimum bid at $100,000. If that seems like a crazy price for an album, Eckstrom would have to agree. He thinks that was far too low.

“That, to me, is a bargain,” Eckstrom says. “It’s something that somebody should have jumped at.”

The record is a stereo version of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan with four deleted tracks that never made it on the final cut, a version that wasn’t known to exist until 29 years after the album’s release. Currently, only two have been documented, and the whereabouts were a mystery to even the most obsessive collectors. But it turns out that one of them is in Grand Prairie, and has been for quite some time.

“I haven’t talked to anybody,” Eckstrom says. “This is the first time I’ve even let anybody know that I had it. I wouldn’t talk to anybody, until now, 52 years after [the record] was made.”

eBay patrons, it seems, missed a chance to bid on one of the world’s rarest albums.

Before Highway 61 Revisited, before “Like A Rolling Stone,” and before Dylan went electric, he recorded Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. The sophomore studio album and his first to be comprised of almost all original songs captured the Dylan we now think of as the protest singer of a generation.

The earliest recording of Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, the one Eckstrom has, included four songs that didn’t make it onto the final cut, which released May 27, 1963. There are only theories as to why they were scrapped from the album and replaced with four others.

One possibility was censorship. A few weeks before the album’s release, the singer was to perform on The Ed Sullivan Show and had rehearsed the song “Talkin’ John Birch Blues” before CBS executives caught wind. Fearing it could be perceived as libelous to the radically right-wing John Birch Society, they told him to choose another tune. Refusing to be censored, Dylan famously walked out on the show. A common theory is that in the aftermath, Columbia Records, which was owned by CBS, also asked him to remove the song, leading to the reconfiguration of the album. But others argue that the four tracks were simply replaced by superior songs.

“I would bet on the latter,” says Patrick Prince, editor of record collector publication Goldmine Magazine. “This is Dylan we’re talking about here. It’s not like he ran from controversy.”

Whatever the case, that version of the album was not supposed to exist.

“It’s release day. The new Adele came out today.”

Forever Young Records was about to open and David Eckstrom’s employees were hurriedly preparing the new vinyl releases. I followed him into his cramped office, which, at one point, years ago, might have accommodated three, maybe even four people. But Eckstrom is a collector and, as such, sees any extra room as storage space. I barely fit a stool between boxes of old cassette tapes.

Just off the service road of TX-360 in Grand Prairie, the 11,000-square-foot record shop’s entrance was built to make the shopper feel like they’re walking inside a vintage jukebox. Forever Young Records hasn’t changed much in seventeen years. It’s a relic of the nineties intended to look like a relic from the sixties.

Eckstrom opened his original record shop in 1984. Today, at his new location, he claims to have the largest selection of vinyl records in Texas. “I cater to any and everybody,” he said. “I go from the framework of you can’t sell it if you don’t have it.”

Eckstrom wasn’t always a professional collector, though. He has a degree in chemistry, a Masters in Business Administration, and left behind a career as a chemical salesman. The 55-year-old is confident, aware of his eccentricities, but authentically unembarrassed about his new path. “You might not understand, but there’s genetics involved,” he tells me. “There are people that like to collect and there are people that don’t understand us collectors. It’s a passion and it’s also a big waste of time and money. It just depends on your point of view.”

And it was Eckstrom’s particular obsession with Dylan that sparked his collecting. Growing up in Southern California, he would listen to his older brother’s copy of Bringing it Back Home. It wasn’t until he was finishing his MBA at Pepperdine in 1979 when “Baby, Stop Crying” off of Street Legal came on his car radio. Recognizing the voice, he pulled over to the side of the road, turned off the engine, and listened intently. It was the first time he had heard new Dylan.

That year he went to a record store in search of a Japanese released edition of Dylan’s Live From Budokan. He ended up buying it and two additional rare Dylan releases, totaling $64. “‘Am I really going to do this?’” he recalls asking himself. “’Yeah, I’m going to do this. This is fun. I’m going to collect Bob Dylan records.’ I purchased those and haven’t looked back since.”

In 2008, Eckstrom collaborated with art designer Geoff Gans to create a picture book of 150 of his personal record sleeves of Dylan singles released all over the globe. Flipping through, you see that the artwork on a Portugal sleeve for “Lay Lady Lay” differs from the Israel’s (printed in Hebrew), which differs from the Australian sleeve just as China’s diverges from the French design.

“The Bob Dylan people had no idea how much was out there,” Eckstrom says. “It takes an individual like me to acquire or accumulate over the years and put [it] together in a collection.” Dylan’s camp was impressed enough by Eckstrom’s book to include it in an album box set and sell it as tour merchandise.

Eckstrom’s wife and three kids have had no choice but to oblige his obsession. “My wife puts up with me. I provided. I was really good at not spending rent money. I was always good at keeping it, not in moderation, but in control.” He spends more time regretting purchases he didn’t make than ones he did. He chalks up money spent to “opportunity cost”: what’s expensive now could become priceless over time.

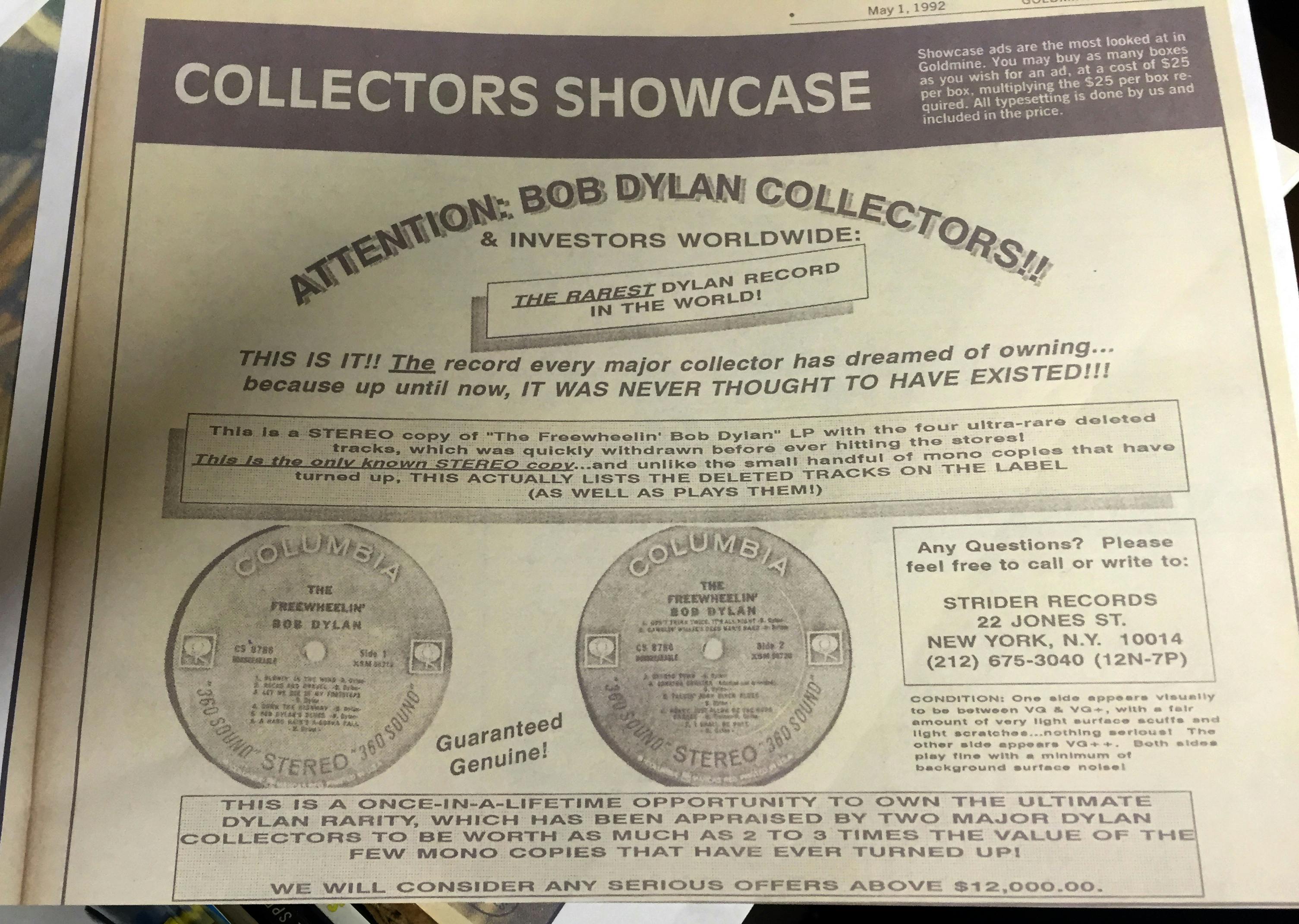

And that was surely his mindset when, in 1992, he opened up an issue of Goldmine to find this advertisement: “ATTENTION: BOB DYLAN COLLECTORS!!” “Oh boy, that’s me,” Eckstrom remembers thinking as he went on to read: “THE RAREST DYLAN RECORD IN THE WORLD!”

“Want to look at it up close, just so you can say you held it?”

Honestly, I did. Vinyl records are already nostalgic, but this bordered on being a historical document.

A New York man was perusing through a church thrift shop when he found it, so the story goes. No one knows how it got there. Perhaps a record executive who had received an advanced copy discarded it years earlier, but eventually, the man who found it put out the ad in Goldmine with a starting bid of $12,000. Eckstrom offered $12,345.67. “Honestly, I didn’t expect to be the winning bidder.”

Others bid higher, but when push came to shove, their money failed to materialize. In this pre-Internet era of sales, Eckstrom won by default.

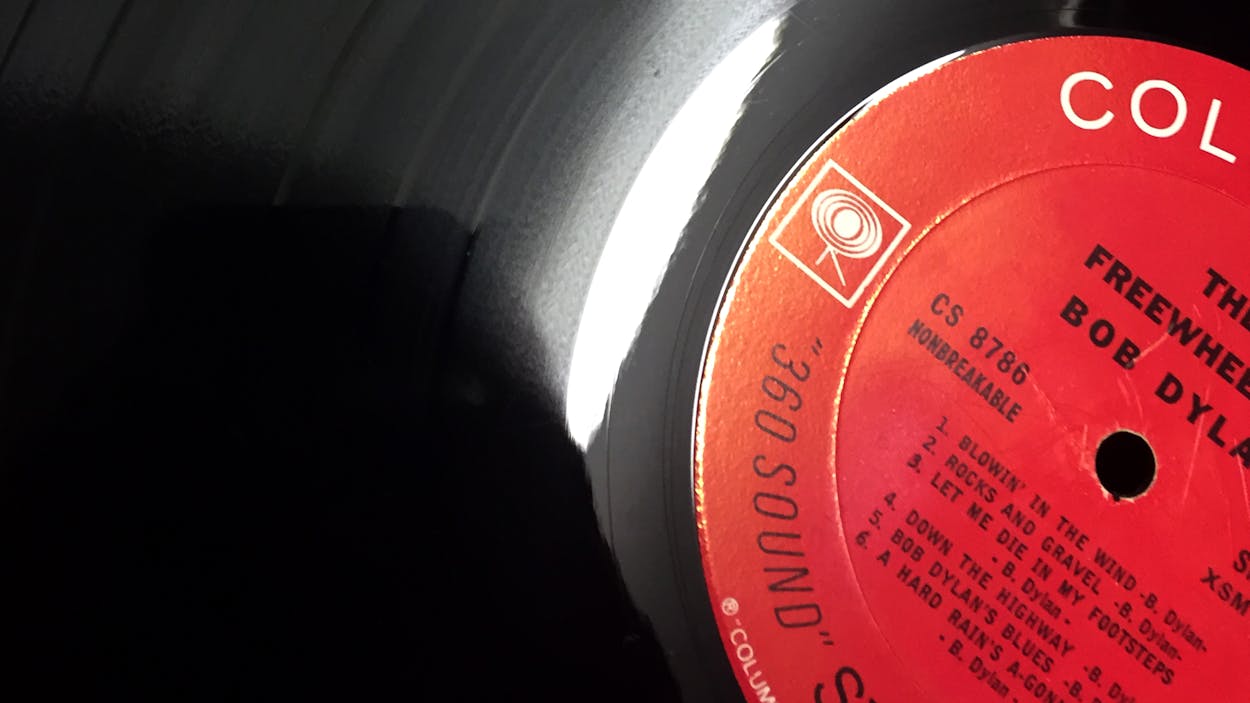

The album came with certificates of authenticity, but Eckstrom didn’t need them to verify what he had purchased. The last track on the wide-release version is “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” which is the longest of any song on the album. On Eckstrom’s copy, it’s the third track, meaning that the longest vinyl grooves are located in the middle of the album.

All mono and stereo versions of the original tracks were supposedly destroyed, but an error at a California pressing plant led to a handful of mono recordings accidentally being printed. Those mono recordings play the deleted tracks, but unlike Eckstrom’s stereo version they are labeled like the mass produced version. There are thought to be less than 20 of those mono versions, and one has been appraised at $15,000. Eckstrom, of course, has a few.

The stereo version, however, actually lists the deleted tracks, even though they’re listed incorrectly. The sixth track is labeled “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and the third track as “Let Me Die In My Footsteps,” but they actually play in the reverse order. If you look closely at Eckstrom’s album, you can see a previous owner wrote a “6” next to the third track and a “3” next to the sixth. It appears someone else tried to erase those numbers.

Eckstrom’s only played it a few times in 25 years, because for him it’s not about listening. It’s about documenting its existence.

It’s difficult to say how valuable the record really is because it is too rare to have much precedent. “Reasonable is not a word I would use,” Prince says of the album’s asking price. “But it depends on the market. It’s definitely one of the world’s rarest.”

Eckstrom is steadfast in resfusing to lower his asking price. He told me that a private buyer offered him $100,000 over a year ago, but Eckstrom didn’t sell “because it wasn’t a public auction. I felt it was important that it be known.” He said his next step is to take it to an auction house like Christie’s or Sotheby’s for a more formal sale.

Although Eckstrom’s original eBay listing may have gotten more laughs than bids, there is a precedent for rare records selling. In early December, Ringo Starr put his original mono pressing of The Beatles’ The White Album up for auction. Prior to the sale, it was officially estimated to go for $40,000 to $60,000. The final bid, including a 20 percent auction fee, was $790,000, shattering world records for a vinyl sale. That proves that money and extreme fandom have led to some hefty bids and sales. After all, it’s not every day—it’s not every decade—you stumble upon one of the world’s rarest albums.