On a sunny October afternoon twenty-five years ago, Sam Carney and his wife, Patricia Kemp Carney, stopped at a Luby’s cafeteria to celebrate National Boss’s Day. Pat, who was the director of elementary curriculum for the Cleburne Independent School District, was technically her husband’s boss (he was working as a truant officer at the time). So Sam and a few co-workers were treating Pat and other superiors to lunch, with the added bonus of the couple getting to spend some time together.

The couple’s three adult children, Rick Carney, Nikki Wilson, and Renea Gilmore, lived nearby, and Pat and Sam phoned their eldest, Rick, who was working as a physical education instructor at a junior college close to the restaurant, to see if he wanted to join. Rick remembers deliberating over whether to meet his parents or head back to the college. He ultimately decided to drive back to work, a decision that haunted him for years, but that also could have saved his life.

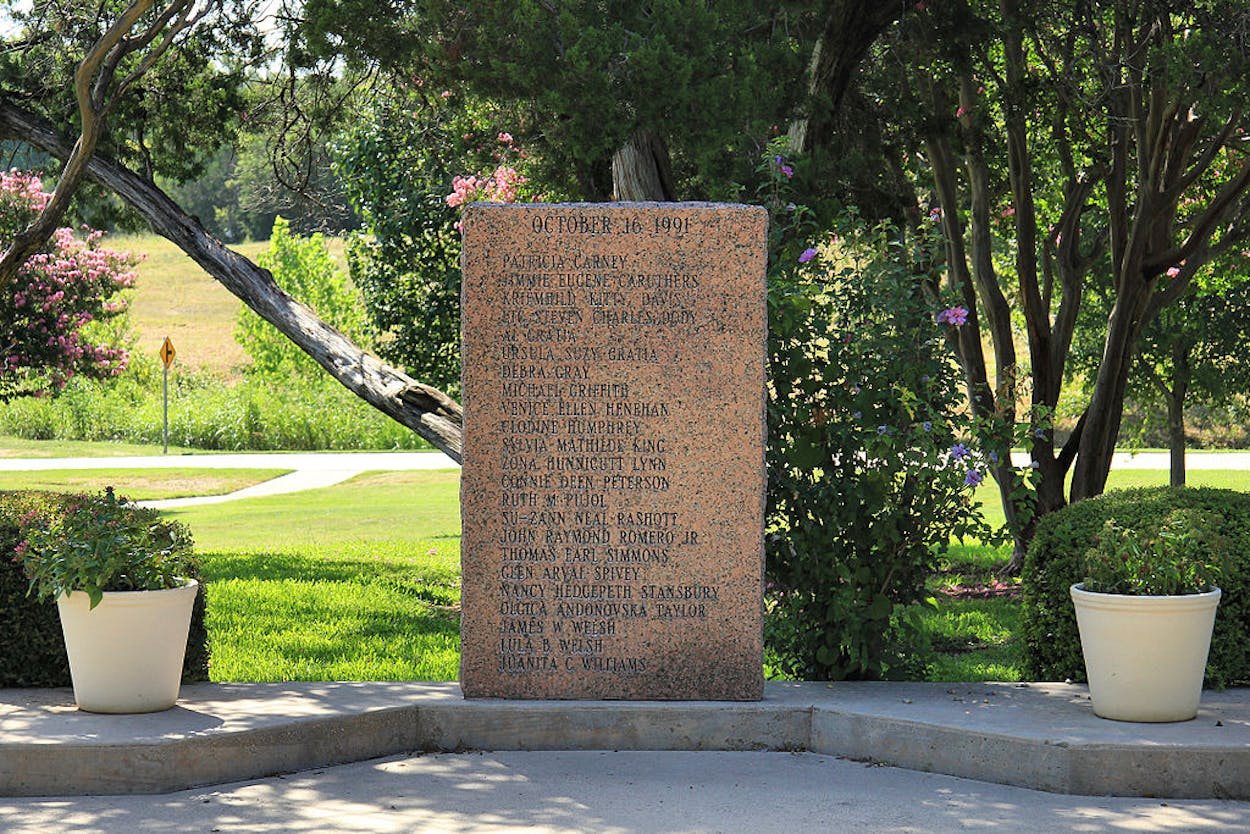

On October 16, 1991 the families of more than 20 victims were forever changed, including my own. At the time, the Luby’s massacre was the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history, a time when this kind of violence was virtually unthinkable to most Americans. It was a pre-Columbine world, and there were few major gun-related tragedies that had marred our cultural landscape. It was a more innocent time, before clear backpacks and metal detectors became de rigeur on high school campuses. My Great Uncle Sam would live to tell the story of how a simple stop at Luby’s changed his life, and the lives of many Americans, forever. But my Great Aunt Pat, tragically, would not.

Sam and Pat lived in the lake house they’d built on Belton Lake, just two hours south of Cleburne, where they attended high school together. Described as a wild party boy known for his athletic achievements as a star football player, Sam never crossed paths with the studious, overachieving Pat, though they were aware of each other from a distance. “She probably wouldn’t have dated someone like him in high school,” their son, Rick, said.

Rick tells stories of his carousing, “wildcat” father getting kicked out of his first college before transferring to Howard Payne University in Brownwood. It was there that he and Pat reconnected and fell in love. When they were students, Pat kept Sam on the straight and narrow academically, tutoring and encouraging him through his studies until they both graduated and became educators. Sam and Pat’s teaching careers took them to Odessa, where Sam was a football coach, before the couple headed to Killeen in 1964. It’s where Sam taught and coached for 32 years.

Pat was a tall woman, towering over her five-foot-seven husband by three inches, so Sam looked up to her in both a literal and metaphorical sense. The couple’s nephew David Carney grew up close to the family, riding bikes and horses with Rick, and being escorted to the bus stop in the mornings by his aunt and uncle. He remembers Pat as the “serious one” who kept Sam in check. “They were like Mutt and Jeff,” he said. “Pat didn’t bullshit around. She didn’t make nothing up.” That made her the perfect complement to Sam, the affable jokester, who kept her laughing “all the time” as David remembers.

Pat, a charter member of Trinity Baptist Church of Killeen, also served as a spiritual anchor for her family. Rick recalled finding her Bible among the things he cleared from her desk. He felt comforted seeing it worn and underlined, with highlighted passages that he feels revealed her strong character.

That character showed through her relationships with students. As a truant officer in the last several years of his career, Sam’s job involved catching kids who skipped class and phoning their parents. (David laughed as he recalls his free-wheeling uncle’s career transition. “I thought, are you kidding me? Sam went from coaching to being a truant officer?”) On the job, Sam often met young men who were down on their luck, and sometimes needed a place to stay. It didn’t take much to convince Pat to welcome these children into their home when they felt called to, letting them stay for weeks, sometimes months at a time.

Rick, a retired school teacher himself, remembers his parents’ careers fondly, noting that, in his opinion, education is the perfect profession for raising a family. “Teachers make pretty good parents, because they’ve been on both sides of the fence,” he said. “It’s probably why me and my wife wanted to be teachers.” Pat’s successful career in education, during which she taught all levels of public school, spanned 37 years and eventually put her in a supervisory role. But on Boss’s Day in 1991, a time that should have been a celebration of her achievements, was irreparably marred by a man named George Hennard.

Pat and Sam were seated at separate tables at the Luby’s lunch outing. The mood was lively when, out of nowhere, their meal was interrupted by shattered glass and mayhem. Hennard had driven his Ford Ranger pickup through the glass windows of the cafeteria. He leapt out of his vehicle shouting, “This is for the women of Bell County,” as he lay siege to the restaurant.

The 35-year-old former merchant mariner’s infamous thirteen-minute shooting spree targeted women, who he repeatedly called “treacherous female vipers” during the incident. Hennard, who had recently harrassed two young sisters who lived next door to him with long, episodic letters in which he called them his “teenage groupie fans,” punished fourteen women that day, many at close range, including Pat.

The couple was separated during the initial commotion and about halfway through the calculated rampage, a heavyset man ran through a glass-plate window. Sam saw a way out. “Dad happened to see it and grabbed a lady’s hand, but when he made his way to the window, he realized it wasn’t Mom,” Rick said.

A coworker seated near Pat hit the ground with her when the truck barrelled through the window, and they tried to hide as soon as shots rang out. The two women could hear Hennard firing off rounds and inching closer and closer, as the coworker whispered to Pat, “It looks like we’re fixing to meet the Lord.” The women were huddled so closely together that when Hennard shot Pat, the other woman thought she’d been shot too. The force of the gunshot, the blood splatter—she thought it was her own. The woman didn’t hear any more firing after Pat was shot, and it’s thought that Pat was the last or second-to-last victim.

Rick had just gotten back to the college when he saw his colleague run down the stairs to the gym, panicked. “She said there was a tragedy and my mom had been shot,” Rick recalled. “Yes, it was definitely her, and she didn’t make it. My knees buckled and I just didn’t know what to do. I obviously started crying and kept trying to rationalize it, thinking this has to be a mistake.”

A family friend who had been dining with the group had to physically restrain Sam from re-entering the restaurant, but the attempt to save his wife couldn’t erase the guilt Sam and other survivors would live with, the feeling like there’s something he should have or could have done to save her. “We all knew he was suffering in that respect,” Rick said. “They were in a good place when this happened. They were very close, all of us were.” But despite Pat’s execution-style death, Rick recalls his father saying she had a calm look on her face when he identified her body a few short hours later. “She didn’t look startled. She looked very peaceful,” Rick remembered. That realization helped him cope in the weeks and months to follow.

Pat’s memorial service was a full house. So many friends, students, and people she’d touched responded to her funeral announcement that the venue had to be changed to accommodate a larger crowd, and even then, Rick said there were people who couldn’t get in for the ceremony.

But the media was also eager to capture the family’s time of grieving, and camped out as close as they could get to the church. “We had to ask the police to help keep them away from us,” Rick said. “And it wasn’t the local media, it was the national media. They were ruthless. The sheriff told me, ‘We can’t keep them from being there, but we can make them show up across the street.’ The local authorities did all they could do to minimize the crap that comes with something like that. I remember Dad saying that several TV shows called him. Oprah called him. He declined and didn’t do interviews. None of us did. Everybody deals with it their own way but we chose the more private route.”

Pat’s death is the sort of thing no family expects to deal with, especially in the days before mass shootings seem to be habitual. “At that time these things didn’t happen hardly. Nowadays it’s not as bizarre. I’m not condoning it, but with the media now you see stuff everyday,” Rick said. Any death in the family is a bombshell, but the shock of hearing a loved one was lost in a gruesome cafeteria shootout was unthinkable, unbearable.

Eventually, though, the family and the world moved forward. Sam soon remarried and he and his wife took frequent trips to Las Vegas with other couples. His new wife lost her ex-husband in a car wreck shortly after they got together. I like to think a shared grief deepened their bond and ability to care for each other. And to this day, Rick receives phone calls, emails, and is approached by strangers who want to tell him how much his mom meant to them.

The shooting also created lasting impact on open-carry laws and gun legislation in Texas. Suzanna Hupp, a survivor who lost both of her parents in the massacre, became a staunch gun rights activist after that day. Hupp, who was 32 at the time of the attack, had left her gun outside in her car in keeping with Texas’ concealed weapons law. When Hupp reached for her weapon in her purse, she realized it was “a hundred feet away,” and that she was defenseless against Hennard.

Hupp went on to testify before Congress in support of concealed-handgun laws, believing that if she’d had access to her weapon, she would have been able to fight back, and her parents and other victims of the shooting, like my Great Aunt Pat, would still be alive today. Losing her parents at Luby’s drove her to politics. She went on to be elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1996, and helped pass a concealed-weapons bill signed by then-governor George W. Bush.

The Luby’s massacre is especially haunting in light of all the mass shootings that have taken place after it. Since 2006, there have been more than two hundred mass killings in the United States. On average, there’s a mass killing about every two weeks, according to research by USA Today.

I never had the opportunity to meet my great aunt. All I know is that she was a tough Texas woman who was fiercely devoted to her family and her career. She’s long been remembered as simply a victim of one of the nation’s most heinous mass murders, a name on a list, but she’s the stock I come from. She went to her death head held high, secure in her convictions, and with no regrets about how she’d lived her life. She was a “one-in-a-million” type to all who knew her. For 25 years, my family has refused to give interviews until opening up to me now. But honoring Pat by sharing her story is the best way I know to preserve her legacy.