Invasive species are on the rise across the U.S., but they just seem more extreme in Texas. Other states have mild threats, such as California’s graceful mute swan or New York’s stylish spotted lanternfly. We’ve got crazy ants that chew through the insulation on electrical wiring, feral hogs that stomp lawns into mud pits, and zebra mussels that slice open swimmers’ feet. The latest animal to expand its territory in Texas is a poisonous, slimy, and sort-of-immortal creature that may well be lurking in your garden at this very moment. Let’s get to know your new nightmare, the hammerhead worm!

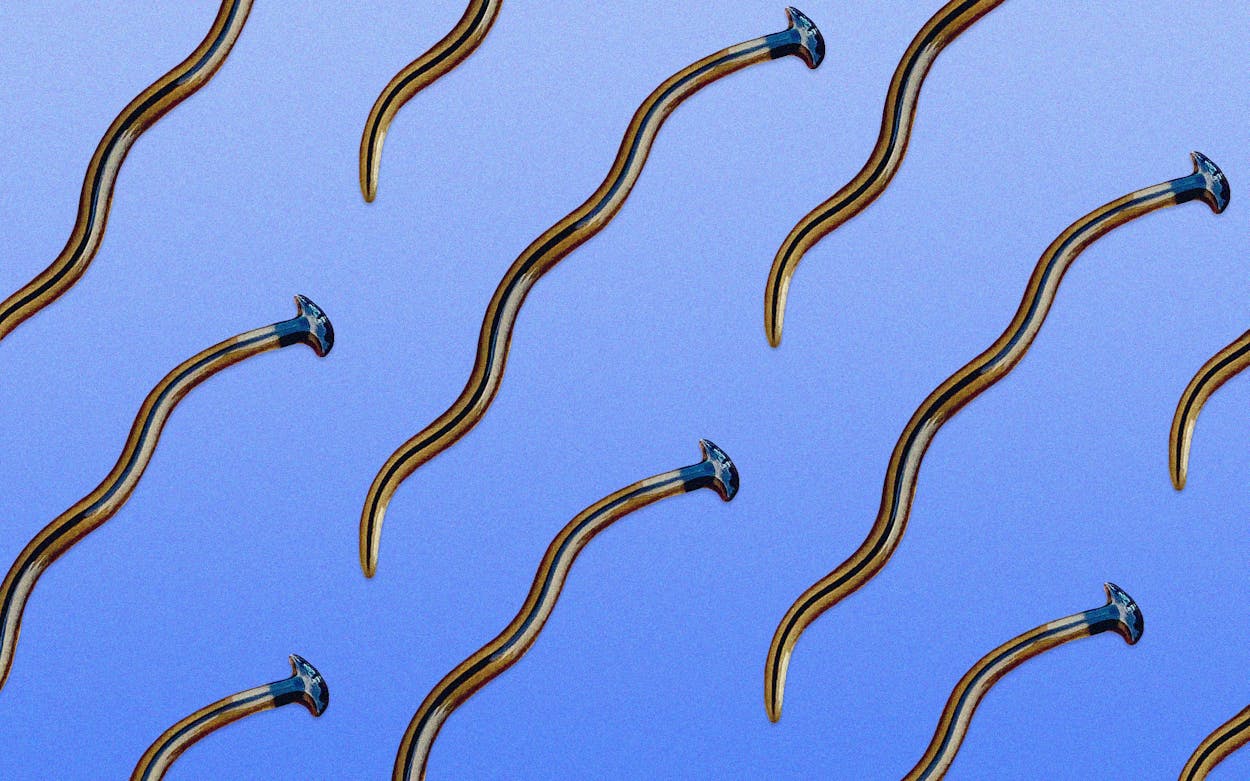

The aptly named invertebrate is easily identified by its creepy, spade-shaped noggin. “It doesn’t look like anything else we’ve seen,” says Ashley Morgan-Olvera, research and education director with the Texas Invasive Species Institute. “We knew it to be in East Texas, but it’s also in North, Central, and South Texas—so pretty much everywhere but our dry, arid areas.” Good news, West Texans! While you do have to watch out for acid-spewing “land lobsters,” you get a pass on this one, at least for now.

The worm can reach about a foot in length, though six inches is more typical. Texas is actually home to two hammerhead species: Bipalium kewense, which is more commonly seen, and Bipalium vagum. Both often have a dark stripe down the middle. The latter is smaller, topping out at about two inches, and only began popping up in Texas within the past few years. The larger species is a threat because it eats earthworms, which play a vital role in keeping soil healthy and rich. “If earthworms were eliminated, then our plants aren’t getting the nutrients they need,” Morgan-Olvera says. “This could impact how our yards, our gardens, and our crop fields grow.”

Encountering a hammerhead worm isn’t the most pleasant experience for humans and pets, either. Hammerheads are the only terrestrial invertebrates known to secrete a neurotoxin called tetrodotoxin—the same poison in pufferfish. Touching one of these worms won’t seriously hurt you, but it might briefly cause your hands to tingle or go numb. Dogs have also been known to eat them, to ill effect. “The worm won’t kill pets, but it will leave them feeling sick for about a day,” Morgan-Olvera says. “I’ve talked to vets who have dealt with animals that ingested these flatworms, and the animals were fine the next day.” She adds: “They definitely did not try to eat the flatworm again.”

Native to Southeast Asia, hammerhead worms were first found in the U.S. in the early 1900s, after apparently hitchhiking on shipments of plants. But Morgan-Olvera’s team has received many more reports of sightings across Texas, including in Austin and San Antonio, in the past few years. No one is sure if that means the number of worms is on the rise, though. The spike in sightings could just be a result of increased public awareness, which is partly due to a number of recent stories (like this one).

If you spot a hammerhead worm, you should kill it. Your first instinct might be to chop it with a shovel, but that’s actually the worst thing you could do. Flatworms reproduce by ripping themselves in half, so if you cut it, the worm will simply become two worms. This is a pretty crazy trait that once led the Atlantic science writer Ed Yong to marvel that “Flatworms Are Metal.” It’s also why hammerheads are sometimes described as immortal, though that’s a bit of a stretch. “They are very mortal,” Morgan-Olvera says. “They do not survive vinegar or salt.” If you spot one, put it in a Ziploc bag—while protecting your hand with a napkin or gloves—and add vinegar or salt. Then seal the bag and throw it away.

Hammerhead worms tend to come out after it rains, and with the unusually wet spring much of the state has had, sightings are up. Morgan-Olvera says you should also be on the lookout after bringing new plants or landscaping into your yard, since the critters are known for hitchhiking in flowerpots and the like. Fond of warm, wet environs, the creatures have also colonized Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, the Carolinas, and other humid places. A warmer planet may be a win for these guys, as a team of scientists wrote last year in a paper reassuringly titled “Hammerhead worms everywhere? Modelling the invasion of bipaliin flatworms in a changing climate.”

Morgan-Olvera and her colleagues at the Texas Invasive Species Institute are calling on Texans to help them track the critters’ range in the state by reporting sightings via email. If you spot a hammerhead in your yard, snap a photo and send it, along with the coordinates of your location, to [email-hidden]. Then dispatch the worm and breathe a sigh of relief—until the next weird invasive creature comes along.

- More About:

- Critters