The first time I heard the chirping, at dusk, I thought it was an odd species of nocturnally active bird. The chirps were high-pitched, like the sound of a basketball player’s sneakers squeaking against the court, and they occasionally shifted into a quick trill like a cricket’s. This “bird” would keep me up at night, since the frequency of its call was higher than the subtle hum of my white noise machine. It seemed to stay in the same general area, though, somewhat unlike a bird, which led me to google “chirping frog Central Texas.”

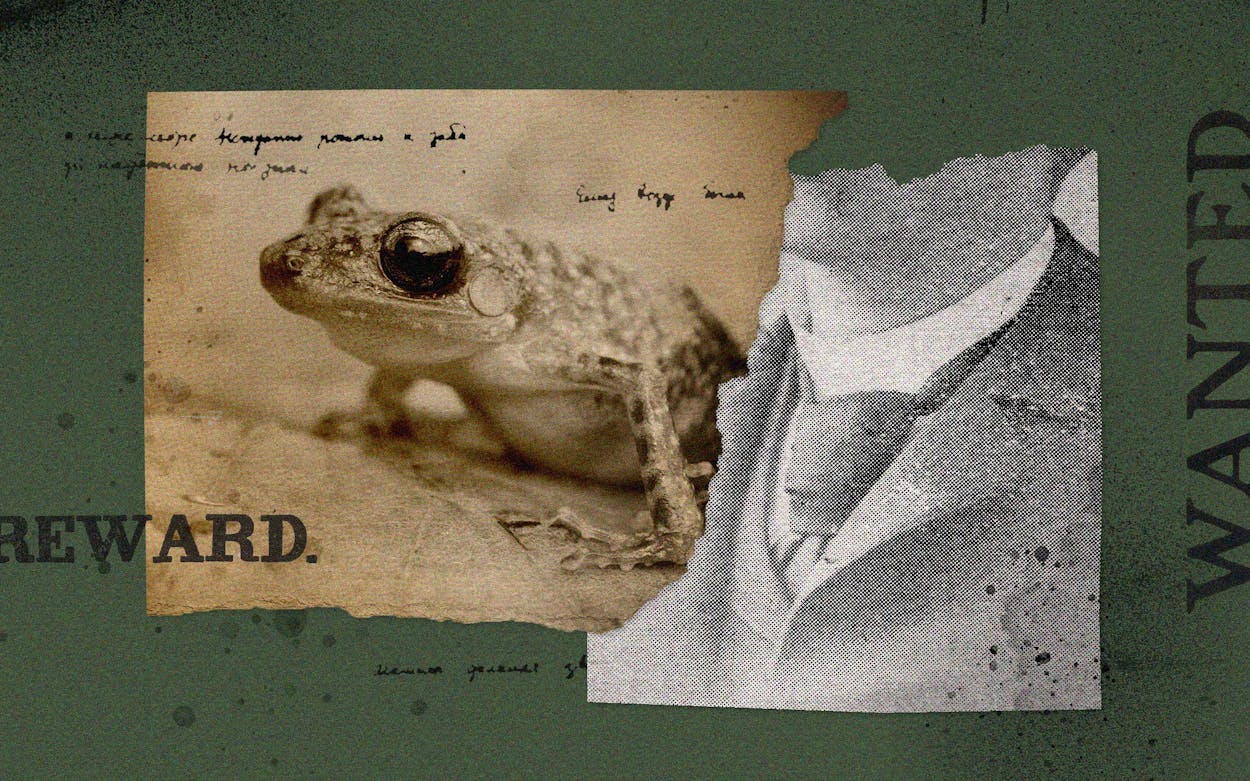

Suddenly an amateur herpetologist, I surmised that it was Eleutherodactylus marnockii, the cliff chirping frog, especially after I listened to some recordings. While the frog typically sticks to rocky outcroppings, it can be found in urban environments as well, ranging across Central and West Texas and into northern Mexico. At my house in Austin, our resident chirping frog resides in the agave below our window, which is a smart spot, since predators can’t get past the spiky plant without great pain. I would know, since I leaned over just a bit too far when the tiny frog peeked out and I moved in to snap a photo (apparently it’s a rare treat to see them, so the spike to the leg was worth it).

During my odyssey through cliff chirping frog research, I found something even more interesting than the frog itself: the man who discovered it in 1878, Gabriel Wilson Marnoch (hence the species name marnockii), a Texas frontier naturalist and Scottish immigrant who lived in Helotes, near San Antonio, during what was known as the Age of Darwin. Incidentally, his father, the surgeon George F. Marnoch, went to school with Darwin back in Edinburgh.

The younger Marnoch was well-connected with scientists across the country, serving as a field correspondent for the paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, often sending samples to him in the mail (Cope was the one who named the cliff chirping frog after Marnoch). Which brings us to some serious Wild West–style drama.

In 1877, Marnoch sent a package containing “turtle remains” to one Professor Joseph Leidy of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Leidy reported back to Marnoch that the package showed up in “ruins.” Who was to blame? Allegedly the postmaster, Carl “Charles” Mueller, who confronted Marnoch at a drunken meal in 1878, believing Marnoch had reported him to the post office headquarters in D.C., which had subsequently charged him with “official misconduct as postmaster.” This turned out to be a deadly mistake—Marnoch retrieved his shotgun, a tussle ensued, and as Mueller grabbed the barrel, the gun went off. Marnoch had killed him. And all this over a turtle fossil.

But, allegedly, that wasn’t the only suspicious death involving Marnoch. In Cynthia Leal Massey’s book Death of a Texas Ranger, the longtime Helotes resident describes both the postmaster killing as well as the killing of Texas Ranger John Green by another Ranger, Cesario Menchaca. Menchaca’s great-grandson, Lawrence Morales, gave Massey some more background than what could be found in old records.

“I thought, ‘Man, this is a great story,’ ” Massey told me, “but it got even greater when I found out Marnoch was involved . . . because he’s such an interesting character. So I said, ‘How was he involved?,’ and his grandson said, ‘Oh, he put out a bounty, everyone knows that.’ ”

The story started when Marnoch got in trouble with the law. In 1871, Menchaca, then a constable, tracked him down by Helotes Creek (where he eventually discovered the cliff chirping frog) and arrested him for catching a stray horse and not reporting it or showing up to court to answer for his crime. Marnoch resisted, at which point Menchaca allegedly “lassoed him and dragged him through town,” according to Morales. Marnoch was peeved enough by this humiliation to take out a bounty on Menchaca’s head, offering $500 (a large sum at the time) for anyone who would kill him. Understandably, this troubled the frontier lawman, who, after joining the Texas Ranger troop, seemed to believe that John Green, his troop sergeant, might be the one to take the bounty, ultimately prompting Menchaca to kill first—some say in self-defense.

Marnoch was never officially linked to that killing. And after two trials over the death of the postmaster, an appeals court declared that the convicting jury hadn’t properly understood the laws of self-defense. Then, because Marnoch’s lawyers could no longer recall important witnesses, the case was dismissed.

“At one point, he had four lawyers for a couple of cases that were ongoing,” Massey said. “They had two in Bexar County and two in Kendall County. And because he had such good lawyers, he usually got off. I mean, he was always getting off of whatever rap it was against him, usually for the theft of a horse. There was a case where they accused him of not delivering the cotton during the Civil War. He and his father were able to get off of that. Money talks, you know, even then as it does now.”

In between all his various crimes, though, Marnoch was finding fossils and live specimens and hosting paleontologists, and he eventually became a schoolteacher and school trustee, as well as—seriously—the Helotes postmaster (meaning he had only himself to blame for any broken fossils). In addition to the cliff chirping frog, he discovered a number of other new species “within a stone’s throw of his home,” according to a 1933 article in the herpetology journal Copeia. These include what Cope called Lithodytes latrans (commonly known as the barking frog) and Coleonyx brevis (the Texas banded gecko). Marnoch’s herpetology collections can be found at the Smithsonian as well as at Baylor’s own Mayborn Museum.

In the 1800s, the wide variety of fauna in Texas attracted explorers and naturalists from all over the globe. Marnoch was one member of this motley crew of frontier scientists. “Texas had a lot of naturalists coming through from the very beginning,” Massey says. “It was a virgin hunting ground, basically. And there were a lot of animals out here.”

These days, many amateur naturalists take to apps like National Geographic’s iNaturalist to log observations and photos, as well as get feedback and identifications from scientists and researchers. It’s a great way to crowdsource data on biodiversity and distribution of species. Luckily, no iNaturalist-adjacent killings have occurred (that we know of).

Like Marnoch, the cliff chirping frog is a bit of an oddball. Unlike most other frog species, according to Michael S. Price, a curator of the “Herps of Texas” project on iNaturalist, cliff chirping frogs “do not undergo a typical amphibian metamorphosis.” Most frogs take to water and lay eggs that hatch into tadpoles. Instead, the cliff chirper lays its eggs in humid areas, usually under leaf litter or rocks, and fully formed little froglets emerge. This ability to thrive away from water means the species is widespread—which explains why you might hear that annoying chirp in your yard at night, perhaps from beneath a planter or, like with “my” frog, beneath the agave (where I’ve noticed green anoles also tend to make their home). The frogs’ other strange trait is that they’re more likely to crawl or walk than to hop, befitting their typical habitat of rocky crevices, where it’s easy for them to fit—they rarely exceed the size of a quarter. Cliff chirping frogs are generally lighter in color in the west and darker in the east, though the color depends on the surrounding rocks. Dark or light, they’re always spotted or mottled.

Thanks to iNaturalist, I later discovered that what I thought was a cliff chirping frog was actually a Rio Grande chirping frog, which looks very similar to the untrained eye. Tom Devitt, a professor and research scientist at UT-Austin, confirmed this ID, noting the fingertips and color pattern. Disappointingly, there are no known crimes associated with the Rio Grande chirping frog.

Either way, it has stopped chirping recently, so I like to think it’s accomplished its task of enticing a female with his squeaky song—perhaps she even laid her eggs in the shade and humidity of the agave. Even though my frog wasn’t the cliff chirper, every time I hear chirping in the night, I’ll think about Marnoch following that same sound to his discovery—and, of course, about his other accomplishments and misdeeds.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Critters

- Helotes

- Austin