This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When football season ended and there was nothing much to do on Friday nights except drink beer and stare up at the wide-open sky, teenagers used to park their pickups across the street from Odessa High School and wait to see the ghost they called Betty. According to legend, she would appear at the windows of the school auditorium at midnight—provided that students flashed their headlights three times or honked their horn and called out her name. The real Betty, it was said, had attended Odessa High decades before and had acted in a number of plays on the auditorium’s stage. But the facts of her death had been muddled with time, and each story was as apocryphal as the last: She had fallen off a ladder in the auditorium and broken her neck, students said. She had hanged herself in the theater. Her boyfriend, who was a varsity football player, had shot her onstage during a play.

So many teenagers made the late-night pilgrimage to see Betty that the high school deemed it prudent to paint over the windows of the school auditorium. During a later renovation, its facade was covered with bricks. But the stories about Betty never went away. Students still talk of “a presence” in the auditorium, one that is to blame for a long list of strange occurrences, from flickering lights and noises that cannot be explained to objects that appear to move on their own. Some claim to have seen her pacing the balcony or heard her footsteps behind them, only to find no one there. Rumors have flourished that a coach who knew the real Betty is visited by her, on occasion, in the field house and that a former vice principal who once caught a glimpse of her after hours was so spooked by the encounter that he refused to be in the school again by himself. “I hear her name on a daily basis,” says theater arts teacher Carl Moore, who has taught at Odessa High for four years. “Whenever something unexplained happens—a book falls on the floor in my classroom or the light board goes out during a technical rehearsal—someone always jokes, ‘It’s Betty.’”

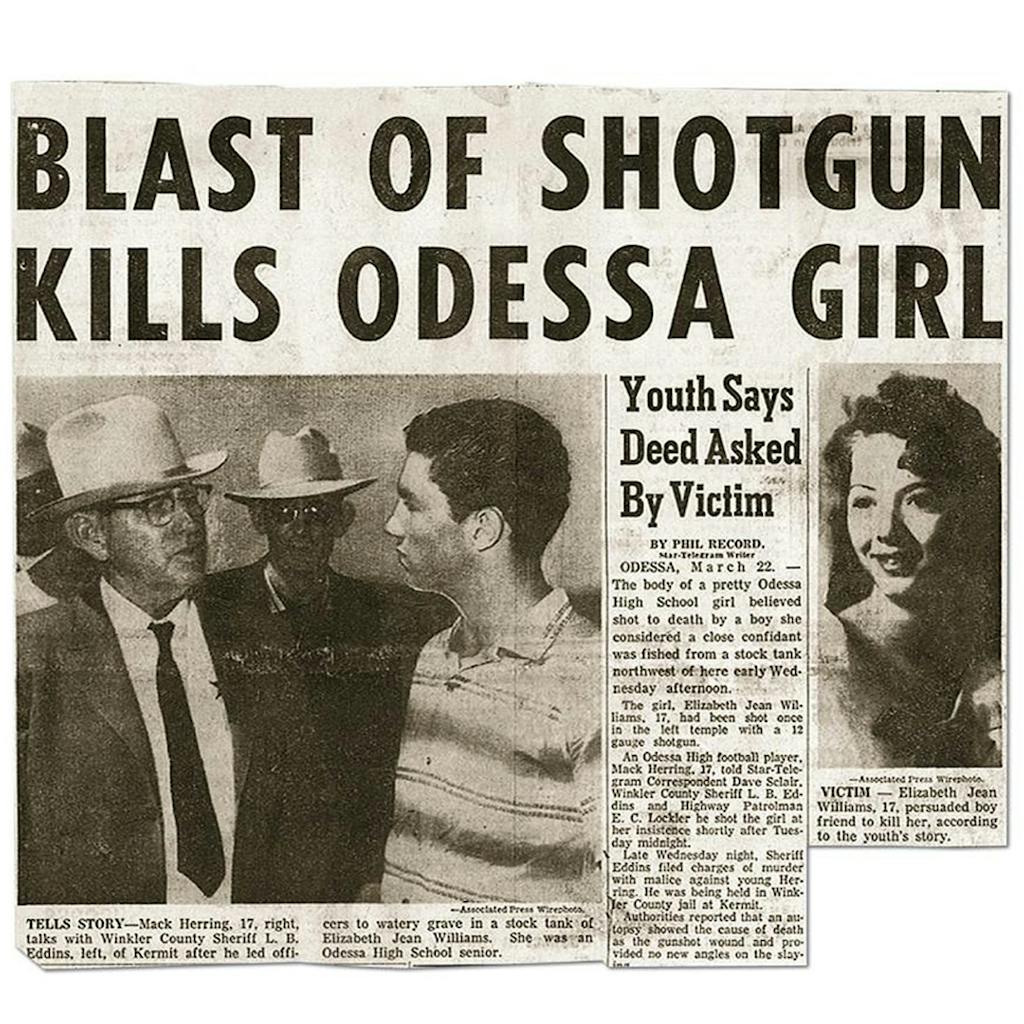

What may be nothing more than just a ghost story can also be seen as something more complicated—as a metaphor, perhaps, for the way that one crime has lodged, uneasily, in Odessa’s collective memory. The teenagers who pass down stories about Betty are too young to remember the Kiss and Kill Murder, as it was christened by the press in 1961, but it was the most sensational crime in West Texas in its day. The notoriety of the case has long since faded, yet 45 years later, something lingers. When Ronnie White, who graduated from Odessa High the year that the murder took place, returned to his alma mater to teach history, in 1978, he was astonished to hear students talking about the former drama student named Betty whose spirit supposedly haunted the auditorium and the popular football player who had had a hand in her killing. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” he says. “I thought, ‘Good Lord, they must be talking about Betty Williams.’”

September 23 [1960]

Study Hall. . . Well, I’ve finally made the rank of Senior and I can hardly believe it! I really don’t feel much different. We get our Senior rings Wednesday. I’ll be glad.

It sure does feel funny to be on the top of every thing looking down. Seems strange to think that this is really all of high school. Next year???

We had our pictures made last week. If they turn out half-way decent, I’ll send you one. Send me another picture if you have it.

Well, the bell is about to ring so I’ll write more later.

Love,

Betty

What most people remember about Betty Williams is that they hardly noticed her at all. She lived in a small, well-worn frame house on an unpaved street not far from the oil fields west of town, where gas flares burned and drilling-rig lights illuminated the desert at night. Her father, John, was a carpenter who had difficulty finding steady work, and her mother, Mary, had taken a job at J.C. Penney to help make ends meet. A strict Baptist, her father often preached to Betty about sin and eternal damnation, and on more than one Sunday morning, he prayed that she might learn to be a more obedient daughter. At seventeen, Betty was pretty in an unremarkable way, with sandy-blond hair that brushed her shoulders and big, expressive blue eyes that could feign sincerity when talking to authority figures but were alive with irreverence.

Betty disdained conformity and reserved particular contempt for the girls with matching sweater sets and saddle shoes who seemed to look right through her. She fancied herself an intellectual and put down her opinions on everything from boys to religion in dozens of letters and notes that she passed in study hall. She read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and the poetry of Allen Ginsberg, and she listened to records of Lenny Bruce’s stand-up routines, in which he railed against racism and skewered middle-class hypocrisy. She too liked to get a rise out of people, and she thrived on attention, whether she got it by arriving at Tommy’s Drive-In dressed entirely in black but wearing white lipstick or in jeans and a T-shirt, under which she didn’t bother to put on a bra. She freely expressed opinions that went against the grain, like her belief that segregation was unjust and that blacks should not have to attend a separate high school across the railroad tracks. In bedrock-conservative, blue-collar Odessa—where the John Birch Society’s crusade against communism and other “un-American influences” had struck a chord—she was seen as an oddball. “Most people do not understand me,” Betty wrote to a friend her senior year. “There are people willing to be my friends, but mostly they [are] either too ignorant to understand why I’m like I am, and consequently offer my mind no challenge; or they haven’t the wits to match mine.”

At the top of Odessa High School’s rigid social hierarchy were the “cashmere girls,” as one alumna called them—the girls with perfect complexions from West Odessa’s better neighborhoods who were perennially voted most popular, best personality, and class favorite. At football games, they sat in the stands wearing the ultimate status symbol: their boyfriends’ letter jackets. They belonged to the informal sororities called Tri-Hi-Y clubs—Capri, Sorella, and Amicae—which cherry-picked the most popular high school girls. Betty was hardly Tri-Hi-Y material; in the high school pecking order, her classmates remember her as “a nobody,” “a nonentity,” and “someone on the outside looking in.” But while she struck an antiestablishment pose, the rejection she felt from the other girls still stung. “Betty wanted to be liked,” says her first cousin Shelton Williams, whose memoir, Washed in the Blood, chronicles his coming-of-age in Odessa through the prism of Betty’s murder. “She wanted what we all want—to be totally unique while being completely accepted.”

In a place where fun on a Saturday night might mean deciding to take only right turns while cruising around town, Betty dreamed of her escape. She hoped to one day become an actress, and in her bedroom, where movie posters and playbills covered the walls, she devoured magazines like the Hollywood scandal sheet Confidential. She loved the thrill of the spotlight and was gifted enough that she landed parts in three school plays when she was just a sophomore. During her junior year, when the speech team performed the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet at the University Interscholastic League competition, Betty played the doomed, lovesick heroine. But as desperately as she wanted to propel herself out of Odessa, she was fatalistic about the future. The oldest of four children, she knew that her parents could not afford to send her away to college, and her part-time job at Woolworth’s barely paid enough to finance any kind of getaway. While she aspired to one day appear on the Broadway stage, in the meantime she planned to live at home after graduation and attend Odessa College, just up the street.

Some nights, Betty would slip out the back door after her parents had gone to bed and walk the four blocks to Tommy’s Drive-In, where there were always boys to talk to. Plenty of girls were flirts, but few of them were as assertive as Betty. She made no secret of the fact that she was not a prude and that she was willing to prove it. At the end of an evening at Tommy’s, it was not unusual for her to end up parked in a secluded spot somewhere with a football player—after, of course, he had taken his girlfriend home to meet her curfew. While boys were free to do as they pleased, “good” girls were expected to obey an unspoken code of conduct. “If a girl had a steady boyfriend, then she could have sex, as long as she didn’t advertise it,” says Jean Smith Kiker, a Capri who was a year below Betty. “But if she did it with someone who wasn’t her boyfriend, then she was a pariah.” Betty chose to disregard the rules, and if she had earned herself a reputation, she hardly seemed to care. “Eisenhower had been president during most of our years of growing up, and kids were kept on a very short leash,” remembers classmate Dixon Bowles. “You got the feeling with Betty that she was always straining against that leash, even when it choked her. Maybe especially when it choked her.”

Mack,

Well, I guess you accomplished what you set out to do. You hurt me, more than you’ll ever know. When you handed me that note this morning, you virtually changed the course of my life. I don’t [know] what I expected the note to say, but not that. I’ll not waste time saying that I didn’t deserve it because I guess I did. I’ve never been so hurt in my life and I guess your note was the jolt I needed to get me back on the straight and narrow. I’ve done a lot of things, I know, that were bad and cheap, but I swear before God that I didn’t mean them to be like that. I was just showing off. I know it’s much too late with you, Mack, but I swear that another boy won’t get the chance to say what you said to me. You’ve made me realize that instead of being smart and sophisticated like I thought, I was only being cheap and ugly and whorish.

Forgive me for writing this last note and thank you for reading it. I’ll not trouble you again, and Mack, I haven’t forgotten the good times we had. I really have enjoyed knowing you and I’m awfully sorry that it had to end this way. . . .

Best of luck with your steady girlfriend. I hope she’s the best.

Betty

P.S. When you think of me try to think of the good times we had and not of this.

Mack Herring was not one of the elite football players at Odessa High School on whose shoulders rested the hopes for the 1960 season; as a back for the Bronchos, and one of average abilities, he was just another guy on the team. Tall and good-looking, with jet-black hair that framed a long, contemplative face, Mack was “a guy’s guy,” his classmates remember, who was quiet and self-contained. The oldest son of a homemaker and a World War II veteran who owned an electrical-contracting business, Mack grew up in the solidly middle-class neighborhood that was home to many of his teammates and the Tri-Hi-Y girls they dated. An avid hunter, he was happiest when he could spend a few days bagging dove or quail on his father’s hunting lease north of town or ramble around the oil fields with his .22, plinking jackrabbits. “If Mack wounded an animal when we went hunting, he would pursue it and dispatch it,” says Larry Francell, who grew up across the alley from him. “A lot of kids were cruel—they would shoot something and watch it hobble off—but Mack was different. He didn’t like to see things suffer. If he was going out there to hunt, he was going to kill.”

Although Mack was near the top of the high school caste system and Betty was at the bottom, they managed to strike up a friendship when she was a junior and he was a sophomore. Betty thought she sensed in him a kindred spirit; he seemed more sensitive than the other boys she knew, and she thought there was something lonely and romantic about him. In the summer of 1960, they started dating, and Betty wondered if she might be falling in love; Mack, she told friends, really listened to her. But Mack was careful to be discreet about the time they spent together. He never took Betty to his neighbor Carol McCutchan’s house, where the in crowd gathered for dance parties and rounds of spin the bottle. He never gave her his letter jacket or brought her home to meet his parents.

Perhaps because he had wounded her pride, or maybe just to make him jealous, Betty tried to even the score one night when she parked with one of his best friends, a popular football player who had been voted the most handsome in his class. The stunt soured Mack on the relationship, and by the fall, he had broken things off and started going steady with a pretty redhead in Amicae. “I’ve never been so humiliated and torn to pieces as I am now,” Betty wrote to a friend. “I feel so lonely and deserted I don’t care what happens now or ever. . . . This is pure hell!”

Betty was crushed to discover that fall that Odessa High’s new drama teacher did not see much promise in her and had relegated her to the role of stage manager for the spring production of Maxwell Anderson’s Winterset, a gloomy 1935 play based loosely on the Sacco-Vanzetti case. Worse, she learned that Mack would be playing one of Winterset’s lead roles, a remorseless killer named Trock Estrella. Still reeling from their breakup and depressed at the prospect of not being cast in a single play her senior year, Betty began to feel hopeless. Mack was “the one,” and without him, life wasn’t worth living. “She said she wanted to die if she couldn’t be with Mack,” remembers her cousin Shelton, who was a year her junior at Odessa’s Permian High School. “She told me, ‘I have to get him back.’” Her mood turned darker after her father rummaged through her dresser drawers, looking for evidence of her disobedience. Distraught, Betty confided in a friend that he had found her diary, in which she had detailed her experiences with boys. Though she had pleaded with her father to believe her when she swore to him that she had changed, he could not be convinced. “Betty said that the situation at home was bad,” says the friend, who asked not to be named. “I wanted to help, but I didn’t know what to do. I was sixteen years old.”

By the winter, Betty had started telling friends that she would be better off dead. “Heaven must be a nice place,” she told junior Howard Sellers. She claimed to have halfheartedly tried to kill herself by taking four aspirin. She boasted of climbing up to the auditorium rafters, intending to throw herself onto the stage below, only to find that she lacked the courage. Betty, who had always enjoyed being outrageous, talked about wanting to die to whoever would listen. But the only reaction she was able to provoke was a few eye rolls. The response was always the same: There goes Betty again, trying to be the center of attention. Even when she began acting more erratically during rehearsals for Winterset, her peers wrote off her overwrought confessions about wanting to die as nothing more than a theater girl’s high school histrionics. She informed at least five students working on the play that she wanted to kill herself but didn’t have the nerve. Would they be willing to do it for her, she asked? “No, I don’t think I will,” senior Mike Ware said, passing it off as a joke. A sophomore, Jim Mercer, also deflected the invitation. “I charge for my services,” he kidded, quoting her an impossibly high price.

At a time when Betty felt marginalized by those around her and forsaken by the one boy she loved, death seemed to hold its own allure. Or was she just acting, pushing the boundaries in another bid to catch Mack’s attention? One night he gave her and Howard a ride home from rehearsal, and she made the request of him: Would he be willing to kill her? She would hold the gun to her head, she said, while he pulled the trigger. Mack laughed at the absurdity of the idea, and Betty laughed with him. She even went so far as to write out a wildly melodramatic note clearing him of culpability were he to be apprehended for her murder, a note that Howard would later say had seemed like a joke. But the next afternoon during rehearsal, Betty pulled Mack into the prop room backstage. She was miserable, she told him, and she wanted to die.

It was the week before Winterset was scheduled to premiere, and students were busy running their lines and painting the set as they readied for the final dress rehearsal. In the middle of the chaos, Betty spotted Mike. “It’s been nice knowing you,” she said.

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“I finally talked Mack into killing me,” she said.

Mike shrugged. “I’ll send roses.”

I am consumed with this burning emptiness and loneliness that has taken charge of me, body and soul. I have to fight it! If I am to live I have to fight [or] else it will pull me down, down, down into that thankless pit of fear, pain, and agonized loneliness.

Two days later, on March 22, 1961, the Odessa Police Department received a frantic phone call from Mary Williams, who reported that her daughter was missing. One by one, Betty’s friends were called into the principal’s office, where they were asked to tell what they knew. Ike Nail, a popular junior who had taken Betty home from rehearsal the previous evening, recounted a story that interested investigators. When he had dropped Betty off at ten o’clock, he said, she had suggested that he return in half an hour and meet her in the alley behind her house. As promised, at ten-thirty Betty had snuck out the back door and slipped into his car. The two teenagers had parked in the alley for a while, but they had been startled to see headlights coming toward them. Betty immediately recognized the approaching car as Mack’s. “Oh, my God, I didn’t think he’d come,” she had exclaimed. Ike had been certain Betty was only joking when she had remarked earlier in the evening that Mack had promised to kill her—so certain that he did not try to stop her when she climbed into Mack’s Jeep. As she turned to go, she said to Ike, “I’ve got to call his bluff, even if he kills me.”

Odessa police youth officer Bobby McAlpine sat Mack down to answer a few questions. The football player told a plausible-enough story: He had dropped Betty off outside her parents’ house at midnight and had not seen her since. But inconsistencies in his account led McAlpine to believe that the seventeen-year-old knew more than he was letting on. Had he left Betty at the front door or the back, McAlpine inquired? The front door, Mack answered. And no, he hadn’t waited to see that she’d gotten inside safely. His answer struck McAlpine as peculiar; the officer knew that Betty had been dressed for bed when she had slipped out of the house that night. According to Ike, she had been wearing only pale-pink shorty pajamas and a blue-and-white-striped duster—not the kind of clothes a boy would leave a girl standing in on her front porch at midnight. McAlpine also felt sure that Betty would not have wanted to sneak back into the house through the front door. Mack was brought down to the police station for further questioning, and 45 minutes later, he broke down. Betty had begged him to kill her, he told McAlpine; all he had done was carry out her wishes. He claimed to have committed the crime with a twelve-gauge shotgun that Betty herself had picked out.

Mack led officers to his father’s hunting lease, 26 miles northwest of town, on a lonely piece of scrubland studded with pump jacks. They turned off the highway onto a winding dirt road and continued on until Mack directed them to stop. He showed them where his and Betty’s footprints—his large, hers small—led down a steep incline to a stock tank. Beside the water, the ground was spattered with blood. In a flat monotone, Mack told investigators that he had shot Betty next to the stock tank, weighted her down, and submerged her body. Unsure of the exact location of the body in the tank, officers asked Mack if he would retrieve it. He stripped off his red-and-white varsity letter jacket, sport shirt, loafers, blue jeans, and socks and waded into the water until it came to his chest. The assembled group of lawmen fell silent. When he reached the center, Mack oriented himself by looking at the mesquite trees on either side; then he dove under the water and came back up. He began wading back toward land, dragging an object that appeared to be very heavy; when he was near the water’s edge, Odessa police detective Fred Johnson could see that he was holding a pair of human feet. Johnson advised him to leave the body, which was still clad in pale-pink pajamas, in the water. Around Betty’s waist were tied two lead weights. She had been partially decapitated by a single shotgun blast to the head.

“It didn’t move him when he pulled her body out of the water or when he said that he’d put a shotgun to her head,” remembers retired highway patrolman E. C. Locklear. “It was as cold-blooded and premeditated as it could be. What pushed him to do it, none of us knew. Later on, when I put him in the squad car to take him to jail, I said, ‘Mack, didn’t you expect to get caught?’ And he said, ‘Not this quick.’ He showed no emotion or regret or fear. It was like he was talking about shooting a dog.”

Investigators called for an ambulance to be sent to the scene without sounding its siren, but reporters were not far behind. Before Mack was taken to jail, he recounted what had taken place the night before while newsmen from the Odessa American and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram took down his story and six photographers jockeyed for the best angle. On the drive out to the hunting lease, “she was cheerful and chatted about how happy she was going to be when she was dead,” Mack explained. He had parked his Jeep a short distance from the stock tank, and he and Betty had sat there for a while and talked. “She was happy,” he recalled. “She kept saying what it was going to be like in heaven.” Then they had walked down to the pond together. Shivering, Betty had hurried back to the Jeep to retrieve her duster. When she returned to the spot where Mack was waiting for her by the water, she took off her shoes. “I just stood there with the gun,” Mack told reporters. “I said, ‘Give me a kiss to remember you by.’ She gave me a kiss and then said, ‘Thank you, Mack. I will always remember you for that.’ Then she said, ‘Now.’ I raised the gun barrel up, and she took ahold of it with the back of her hand and held it up [to her temple]. And then I pulled the trigger. She was dead—like that.” He snapped his fingers for emphasis.

As word spread around Odessa that afternoon that Mack had been arrested for Betty’s murder, the news was greeted with incredulity. “I just can’t believe it! Not Mack!” a sixteen-year-old girl shrieked as she collapsed in tears against a wall in the police station. “We were shocked that one of our own—a popular football player who had been to our parties and had dated our friends—had committed a heinous crime,” says Jean Smith Kiker. “And as more information came out, we were shocked to learn that Mack, and a lot of the other boys we knew, had been spending time with Betty after they had taken their girlfriends home.” But despite the gruesomeness of the crime and the first-degree murder charges that were filed against him, Mack was not ostracized by his peers. He was still invited to parties at Carol McCutchan’s house and was welcome at Tommy’s Drive-In. Girls visited him at home and boasted of knowing him. Rather than seeing Mack as a killer, many classmates acted as if something tragic that was beyond his control had befallen him. “We were all supportive, because we couldn’t believe it,” says a former Tri-Hi-Y girl who asked not to be identified. “We figured that if Mack did it, then there had to be a good reason.”

After the arrest, the gossip centered less on Mack than it did on Betty. “She was seen as a slut and a diabolical manipulator,” says Shelton Williams. “My father overheard a customer at his car wash say, ‘Everyone knew that girl was no good. She tricked that boy into killing her.’” Betty’s classmates in Winterset, which was canceled after the news of Mack’s arrest, puzzled over her intentions on the last night of her life. Had she really wanted to die, or was she still hoping, somehow, to win Mack back? “I think Betty trapped herself in a real-life drama of her own making,” says Dixon Bowles. “She was ad-libbing all the way, and it spun out of her control. I remember a teacher taking me aside afterward and asking me, ‘Was Betty pregnant?’ And I said, ‘No. I wish it were that simple.’ It was a game of chicken, and she never backed out.”

March 20, 1961

I want everyone to know that what I’m about to do in no way implicates anyone else. I say this to make sure that no blame falls on anyone other than myself.

I have depressing problems that concern, for the most part, myself. I’m waging a war within myself, a war to find the true me and I fear that I am losing the battle. So rather than admit defeat I’m going to beat a quick retreat into the no man’s land of death. As I have only the will and not the fortitude necessary, a friend of mine, seeing how great is my torment, has graciously consented to look after the details.

His name is Mack Herring and I pray that he will not have to suffer for what he is doing for my sake. I take upon myself all blame, for there it lies, on me alone!

Betty Williams

When The State of Texas v. John Mack Herring got under way on February 20, 1962, a guilty verdict seemed to be an all but foregone conclusion. Mack’s own confession painted a picture of a methodically planned murder; before driving Betty half an hour out of town and shooting her, point-blank, in the head, he had, by his own admission, procured lead weights, rope, shotgun shells, and even a miner’s helmet to light his way so he could submerge her body in the stock tank. In the presence of lawmen, he had shown little emotion for his victim. (While in custody, Mack reportedly told a deputy sheriff, “I feel toward her like a cat lying in a muddy street in the rain.”) “It looked, to most people, like a case that was impossible for the defendant to win,” says writer Larry L. King, who had left Midland a decade earlier but still followed the case. “I mean, the defendant had admitted he kissed the girl, then blew her away, weighted her body, and buried it in the pond: What else did the state need?” So King was confounded when his good friend Warren Burnett, an Odessa defense attorney, decided to take the case. “I asked Burnett why and he said, ‘Church ain’t over till they sing.’”

At 34, Burnett was already considered one of the finest trial lawyers around, having earned the sobriquet “the boy wonder of the West.” An ex-Marine who, at the age of 25, had been the youngest prosecutor in Texas, Burnett always brought a sense of theater to the courtroom. In his melodious baritone, he peppered his arguments with Shakespeare and Scripture and won over jurors with his down-home charisma, so much so that no jury had ever sent a client of his to prison. In the Kiss and Kill case, he hatched a plan that he hoped would prevent Mack from ever standing trial for murder, using a defense strategy that had never, to anyone’s recollection, been used before. Under Texas law, if jurors found a defendant temporarily insane—that is, insane only when he committed the crime—he would walk free. Citing this statute, Burnett argued before district court judge G. C. Olsen that before any trial was to take place, jurors should first have to evaluate Mack’s sanity at the time he pulled the trigger. If they determined that he had been temporarily insane, he should not have to stand trial for murder. Burnett’s line of reasoning flouted legal precedent; sanity hearings are supposed to take up only the narrow question of whether a defendant is competent to stand trial. But to the astonishment of courthouse observers and over the strenuous objections of the prosecution, Judge Olsen granted Burnett’s motion for the pretrial hearing. Jurors would not determine Mack’s guilt or innocence; they would only render a decision as to whether he had been insane at the time of the crime. Mack, in effect, would have a chance at acquittal before his murder trial had even begun. When flummoxed prosecutors requested a 24-hour delay to prepare their case, Burnett expressed his surprise, “since insanity is the only possible explanation for this tragedy.”

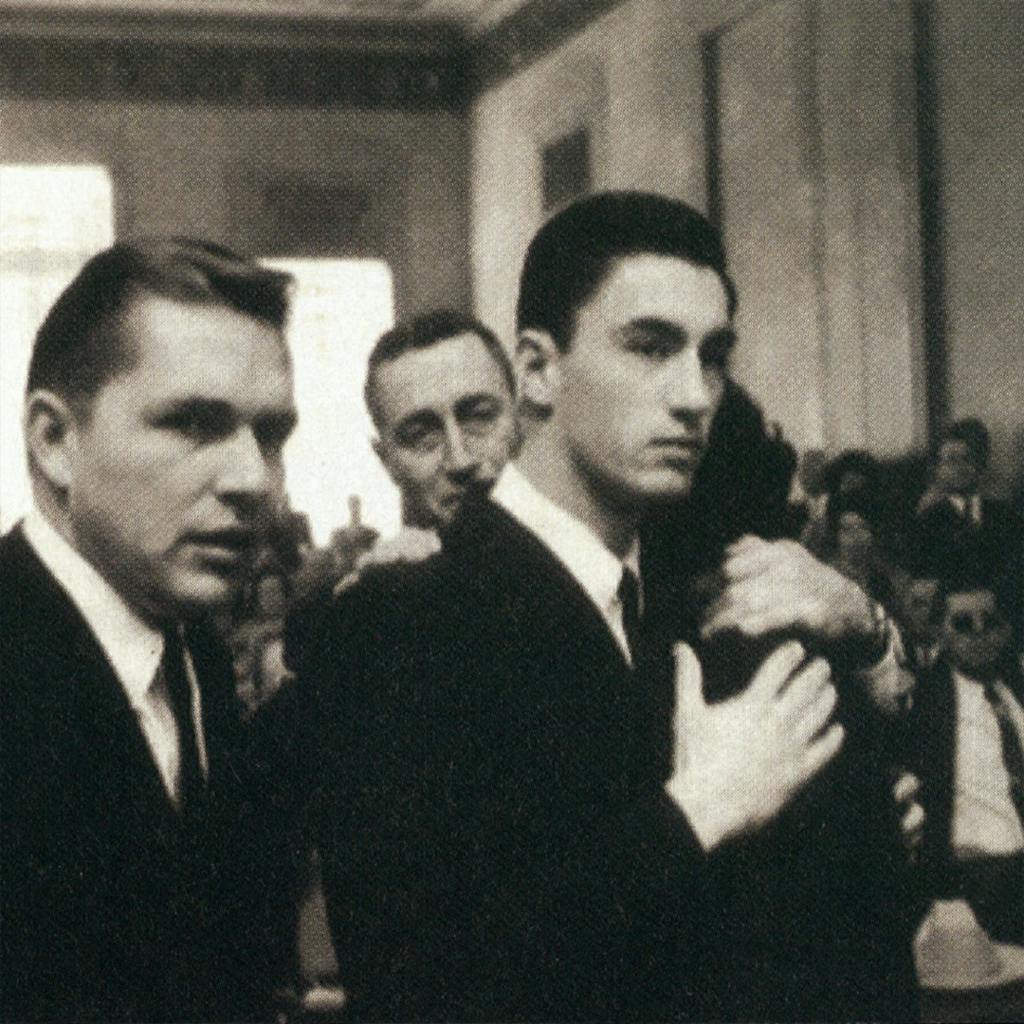

Because the murder had occurred just across the Ector County line, the hearing took place in Kermit, an oil-patch town 45 miles west of Odessa, where the smell of petroleum hung in the air. The jury pool was the largest that had ever been called in Winkler County; the last murder to get much attention—a stabbing at a hotel in Wink—had happened in 1947. Teenagers filled many of the 160 seats in Judge Olsen’s courtroom, at times spilling over into the aisle and out the door. “It was a carnival,” says former Winkler County clerk Virginia Healy. “The defendant was a good-looking boy, and all these clean-cut girls came out from Odessa to ooh and aah over him.” Nicknamed “Mack’s girls,” they made up only a fraction of the spectators whose sympathies were with the defendant. Betty’s parents, lost in their grief, were her only visible supporters; her father occasionally leaned forward so as not to miss a word of testimony, dabbing at his eyes with a white handkerchief. Mack sat behind the defense table in a dark suit, his head often bowed. The strain of the proceedings sometimes showed, as when he laid his head in his hands during jury selection; otherwise, he was impassive. Arguing for the state was 32-year-old district attorney Dan Sullivan, an earnest, if not particularly seasoned, lawyer who was out of his depth; in his sixteen months in office, he had prosecuted mostly oil-field theft cases and DWIs. It was Burnett, with the sleeves of his suit jacket pushed up to his elbows, who commanded the courtroom.

Because the burden of proof fell on Burnett to prove that Mack was insane when he pulled the trigger, the hearing began not with witnesses for the state but for the defense. The first person Burnett called to the stand was Mack’s father, O. H. Herring, who told the jury that on the day of his son’s arrest, Mack had handed him a letter Betty had written. The letter, which the Texas Department of Public Safety had authenticated and which Mr. Herring read to the jury, held that Betty alone was to blame for her death. “You might say she has become a witness for the defense,” Burnett quipped. Nine character witnesses—including Odessa High’s head football coach, Lacy Turner—spoke on Mack’s behalf; many of them concurred that Mack must have been temporarily insane at the time of the crime. Three classmates testified that Betty had also asked them to kill her. But the most compelling testimony came from Marvin Grice, an Odessa psychiatrist who had examined Mack three days after the murder. The former football player had been “dethroned of his reasoning” by Betty’s pleadings, Grice said, and, in his estimation, had been temporarily insane when he put the shotgun to her head. “He became so mixed up and so sick that he felt pulling the trigger was what he should do for her,” Grice testified. “He was deprived of the power of applying logic.” However, the effects of this “gross stress reaction” were temporary. “He can be trusted to lead a normal life,” Grice assured the jury.

Sullivan put on the best case he could given the extraordinary limitations he was working with. Judge Olsen had denied his motion to have Mack evaluated by a psychiatrist for the state, having agreed with Burnett that the defendant’s current state of mind was irrelevant. Sullivan tried to establish jealousy as a motive by calling to the stand Bill Rose, the popular football player whom Betty had parked with when she was dating Mack. But Bill testified that he had spurned Betty’s advances when they had parked in a secluded spot. Besides, Bill maintained, the incident had not had much of an effect on Mack. “We talked a while and agreed our friendship was more valuable than an argument about her,” Bill testified. “We shook hands and forgot the whole thing.” Sullivan pushed on, focusing on classmate Howard Sellers’s comment that Betty’s dramatic note attempting to exonerate Mack had been “conceived in a joking atmosphere.” But the district attorney could not establish a motive. “The entire proceeding was a perversion of the law,” says Sullivan, who is still a practicing lawyer in the nearby town of Andrews. “The jury never heard the indictment read or learned how the crime was committed. None of the facts of the case came out.”

Moments after Sullivan rested his case, Burnett rose from his seat and thundered across the crowded courtroom, “Stand up, Mack Herring! Go around and take the witness chair.” It appeared that Burnett was calling his client to the stand for rebuttal, but no sooner had Mack been sworn in than Burnett, for further dramatic effect, roared, “Pass the witness! Answer the questions they have for you, lad.” If he had hoped to throw the prosecution off balance, he had succeeded, though Sullivan tried to make the most of the opportunity. In his cross-examination, the district attorney pressed Mack to explain at what moment, exactly, he had decided to kill Betty. “I don’t know,” Mack stammered. “I can’t remember . . . I can’t explain.” He had difficulty understanding it all himself, he told the jury in a halting voice. “I have stayed awake at night trying to think so I could explain it to other people,” he said. “Sometimes now I think it was a dream. Sometimes I think it was real. Sometimes I think I am watching someone else.” As he sat in the witness chair, he appeared solemn and contrite. Though other classmates had believed that Betty was joking when she had asked them to kill her, Mack maintained that her pleas had had a profound effect on him. Betty had “talked about heaven a lot,” he said, and had made it appear “like a place you could reach out and touch.” He explained that on the night he killed her, he had believed he was doing the right thing. In retrospect, he told the jury, “I know that everything about it was wrong.”

After eleven hours of deliberation, during which jurors asked that Grice’s expert testimony be read back to them, they determined that Mack had, in fact, been temporarily insane on the night of the murder. Upon hearing the verdict, Mack slumped in his chair and wept, while friends and classmates rushed to his side to embrace him. Betty’s parents slipped through the exuberant crowd and out of the courtroom before reporters could reach them for comment.

While Burnett had been careful not to malign Betty’s character during the hearing, some details of the case, like her sneaking out of her house in her nightclothes to meet Ike Nail, had tarred her as a loose, immoral girl. “I overheard a juror talking about Betty,” says Hazel Locklear, the wife of the highway patrolman who had been struck by Mack’s aloofness at the crime scene. “I remember her saying, in a very ugly way, ‘That girl was nothing.’” To some observers, it seemed as if Betty’s transgressions had eclipsed those of the teenager who’d killed her. “Nobody talked about how Mack could have said no,” observes Sandra Scofield, who graduated from Odessa High a year before the murder. “Betty had enlisted him—this worthy young man—to do what she didn’t have the courage to do herself. She had ‘roped’ him into doing it. So she became not the victim but the villain.”

Sullivan appealed the verdict to the Texas Supreme Court, on the grounds that Judge Olsen did not have the authority to grant a hearing that only evaluated Mack’s sanity at the time of the crime. On June 27, 1962, the court sided with Sullivan, vacating the judgment and ordering a new trial. But what advantage he gained in being allowed to present his evidence was negated by Burnett’s skill and showmanship. Because of the intense publicity, the second trial was moved nearly six hundred miles away, to Beaumont. Burnett relied on his old playbook. He put Grice back on the stand and packed the courtroom with teammates, teachers, parents, and community leaders who took the stand to extol his client’s virtues. Mack had been a stellar student, one of his teachers told the jury, and added, “I’ve never known a more brilliant mind.” His football coach testified that Mack had never used profanity. Howard Sellers said that Mack was his “idol” and “personified everything that was good.”

In an impassioned closing argument that Burnett delivered before a standing-room-only crowd, he hammered home the fact that nearly two years after Betty’s murder, the prosecution had still not established a motive. “Does the evidence show you any possible explanation?” he challenged the jury. “Until some evidence is brought to show the psychiatrists were wrong, I’d be inclined to believe them.” Jurors agreed, and twelve days before Christmas, they found Mack not guilty by reason of insanity. A smattering of applause broke out in the courtroom when the verdict was announced, and once again, Mack was mobbed by jubilant supporters. A few glad observers, including the wife of a Baptist minister who sat on the jury, looked on with tears in their eyes. Mack, who had once worried aloud to a reporter that he would be sent to the electric chair, was a free man.

To whom it may concern,

The time has come to leave, and as I prepare to go, I find it difficult to write the words that will explain . . .

I love you Dick, for all that you have meant to me. You’ve been the greatest friend I could ever ask for. Here’s to all the stories we never wrote. Maybe it’s better that way—they’ll never be exposed to the critics or the public. I hope our story about Jerry makes it. Think of me once in a while and know that I’m glad we met.

Gayle . . . I’m sorry about Indiana, but I hope you’ll understand. Here’s hoping you’ll always have the best because you’re one of the best!

I find the tears clouding my eyes as I say goodbye to those I love. May they forgive me . . .

Mr. Herring, you’re a wonderful man. So many times I’ve wanted to tell you how much I appreciate you. I’m sorry I have to tell you like this. . . .

Memories, so many memories to come back and cloud my mind, memories that I’ll carry through all eternity.

Anyone who had suffered the unrelenting scrutiny that Mack had—the Odessa American alone ran nearly two dozen front-page stories on the case—might have pulled up stakes and started a new life somewhere else. But Mack chose to stay. After attending Texas Tech University, where he was once introduced to a class as “the famous Mack Herring,” he returned home to the town that never turned its back on him. He made a quiet life for himself, and he steered clear of trouble with the law. He married and divorced, twice. He worked as a dock foreman at a chemical company, a carpenter, a welder, and, for at least the past 25 years, as an electrician. Few of his former classmates still see him; most have moved away or fallen out of touch. As the booms and busts of the oil patch have brought new people to Odessa and taken others away, Mack has faded into the background.

I caught sight of him one afternoon in November as he pulled up to his house, a mint-green frame house not far from where he grew up. His own neighborhood lacks the gracious lawns and spreading trees of his childhood; the house, which is a bit down at the heels, looks like the province of a man who lives alone. A meager yard of packed dirt and weeds led to the street, and an old rusted pickup sat in the driveway. Mack, who declined to be interviewed for this article, looked indistinguishable from any other working man in Odessa, right down to his beat-up truck with the toolbox in the bed. Nothing suggested that he had once been sharply handsome or held a great deal of promise. At 62, he was utterly unremarkable.

“This has not been a free ride for Mack,” says his childhood friend Larry Francell. “It’s ruined two lives. One’s dead, one’s still alive.” And because many people in town would prefer never to hear the words “kiss and kill” again, the case still touches a nerve. “I suspect most of us would rather let the thing stay in the past,” one Odessa High School alumna wrote me in an e-mail. “There was already enough pain in ’61. Why dredge it up again?” But others refuse to forget. “I don’t take well to the fact that people don’t think this is an important story,” says Shelton Williams, who carried a photograph of his cousin in his wallet for 35 years after her murder. “I don’t believe that Betty ever wanted to die.” In the Williams family, grandiose threats and melodramatic bids for attention had not been unique to Betty. “When her father lived with my parents, he used to threaten to kill himself in the middle of the night,” says Shelton. “My mother would sit up with him and try to talk him out of it, until he did it one too many times. Then she told him to just go ahead and do it, which he didn’t. When Betty said that life wasn’t worth living without Mack, I understood it within the context of our family.” Her murder and the verdicts that followed had stripped away any of his preconceptions about fairness and justice. “No other event in my life impacted me the way this did,” he says. “Everything looked different to me afterward. Betty had been murdered, and everyone wanted to sweep it under the rug and make it go away.”

And still, after nearly half a century’s worth of other tragedies, the stories at Odessa High School live on. In October an Odessa College student named Sammi Sanchez, who was researching a paper she had to present to her speech class on the best place to spend Halloween, received permission to spend the night in the high school’s auditorium. When I met Sanchez and three of her girlfriends a few weeks later, they told me, in great detail, about all the strange and unexplained things they had heard and seen: the door that had mysteriously slammed closed behind them, the eerie footsteps, the stage lights that had moved when they had called out Betty’s name. After two hours in the auditorium, Sanchez and her friends were so unnerved, and so certain that they had felt Betty’s presence, that they decided to leave. But first they did what they assumed any drama girl—spectral or not—would have wanted. “We let Betty know she was the star,” Sanchez says. “We sat there in the theater seats, in the dark, and we applauded for her.”