For a 65,000-seat stadium, the Alamodome is one hell of a basketball gym. The San Antonio Spurs won their first NBA championship there in 1999 before departing for the AT&T Center, and the NCAA men’s and women’s Final Four has taken place there five times combined. But football? San Antonio built its artificial turf of dreams in 1993, but football didn’t come. Sure, the Dallas Cowboys regularly hold training camps inside the climate-controlled dome, the New Orleans Saints played three games there after Hurricane Katrina, and Notre Dame and Army have each had a “home” game in the River City (though Army’s was against Texas A&M). But the only gridders to ever truly call the Alamodome home were the short-lived San Antonio Texans, who for one season in 1995 competed in the Canadian Football League, squaring off against foes like the Winnipeg Blue Bombers and the Hamilton Tiger-Cats on a 110-yard field.

On September 3, that finally changes, as the University of Texas at San Antonio opens its first-ever football season against Northeastern (Oklahoma) State before what UTSA and city boosters hope will be a nearly sold-out crowd. “This is what we really built the dome for,” enthused former Spurs owner and UTSA donor Red McCombs before the considerably smaller crowd that came out for the Roadrunners’ spring “Football Fiesta” scrimmage in April. Well, not really. Until Red sold the Minnesota Vikings, in 2005, San Antonians thought they might still get an NFL team, not a mostly freshman college football squad, wearing the jersey of a school that didn’t even have athletics until 1981.

In the pantheon of Texas college sports, UTSA barely rates. During the first eighteen years of the program, the Roadrunners qualified for two men’s NCAA basketball tournaments, losing all games, and won small conference titles in tennis, cross-country, and track. Things have improved since Lynn Hickey became UTSA’s athletics director, in 1999. The softball, baseball, women’s golf, and men’s track-and-field teams, and others, have all won conference titles, while men’s basketball notched the school’s first-ever NCAA tournament victory in any sport last March, beating Alabama State in the expanded field of 68. These victories have come against the backdrop of a booming school and city. Chartered in 1969, the university has fewer than 90,000 alumni, but like San Antonio, it is growing fast. Enrollment is now over 30,000, with more and more full-time and residential students, a robust Greek system, and a mascot named Rowdy that you can friend on Facebook (education: “Studied Awesomeness at Texas San Antonio”).

Still, a university without a football team, especially in Texas, is like a song without a chorus. And so, after several years of run-up, UTSA will join Georgia State (Atlanta), Florida Atlantic (Boca Raton), and Florida International (Miami) as recent big-city colleges to launch a football team from scratch. It’s a lengthy process that brings into focus questions fans and school administrators all over the country are already asking, particularly in this big-money, hyper-commercialized sports age: What is college football’s cost? What’s its value? What’s its relationship to the university’s larger mission, both philosophically and in practice?

For UTSA, though, perhaps the most important question is, Can football tradition be created out of thin air? Those other recent start-ups have enjoyed a mostly good reception. America’s appetite for football, both pro and college, live or televised, seems to be basically unlimited. But the stakes are high. The budget for the Roadrunner football team eclipses by a mile any other team’s. Financing it required not only a $15 million fund-raising campaign but also a vote from the UTSA student body to double the athletics fee that’s added to tuition each semester (it passed overwhelmingly). Without a long history of fandom to fall back on, will a few losing seasons dampen their enthusiasm? It’s only partly true that every school wants to have a football team: Every school wants to have a football team that wins.

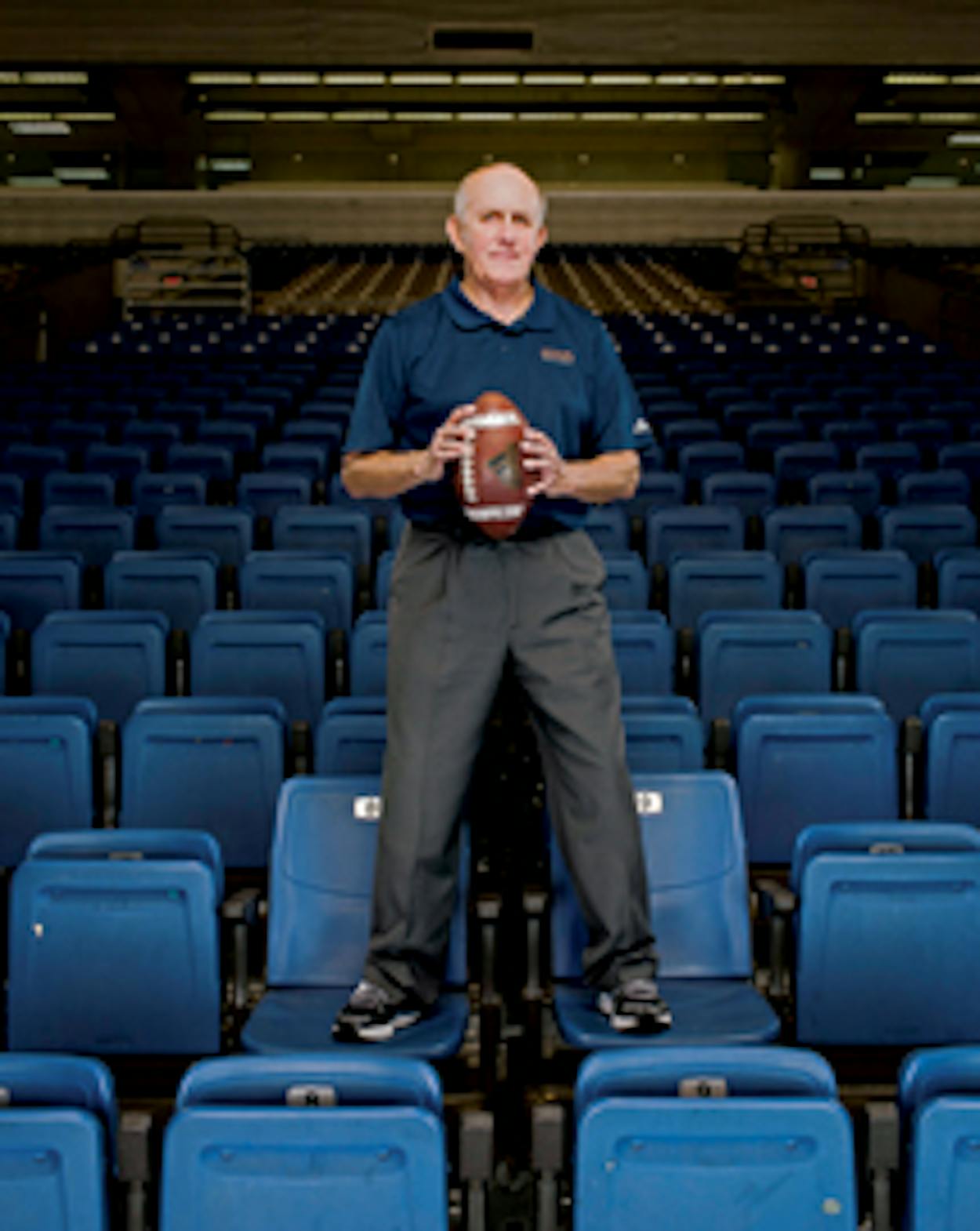

And here is where UTSA’s story gets even more intriguing. The Roadrunners take the field for the first time under the guidance of a head coach who has won at the highest levels. Larry Coker comes to San Antonio with something that even Mack Brown didn’t have when he was hired by the Longhorns (and something that Gary Patterson and TCU are moving to the Big East to have a better chance at getting): a BCS national championship, which Coker earned as the head coach of the 2001 Miami Hurricanes. Coker was also named National Coach of the Year in both that year and 2002. Hickey knew that her first football hire had to make a splash, “but in my wildest dreams, quite honestly, to get the caliber of a Larry Coker here?” she says. “I didn’t know if that was really possible.”

The enthusiasm for Coker and his team was clear on the Saturday of the team’s spring game, when six thousand people turned out for a vanilla football practice with no tackling of the quarterback or special teams. “I think it’s the greatest thing to ever hit San Antonio,” said Jeff Seaman, a 48-year-old salesman with no connection to the university. Elsewhere in the Alamodome stands, fans already accustomed to breaking out the blue and (not burnt) orange for basketball games flashed the thumb and little fingers to make the Roadrunner hand sign (“Get your birds up!”). Many wore T-shirts with the inaugural football schedule printed on the back or the slogan “UTSA Football: Still Undefeated.” A great hook, but it wasn’t thought up by some marketer in anticipation of this season. Rather, it’s been the best-selling T-shirt at the UTSA campus bookstore for twelve years.

Roadrunner football has been in the making just about that long. When Hickey, then the senior associate athletics director at Texas A&M, interviewed for her job in 1999, UTSA president Ricardo Romo asked her flat out what she thought about the possibility of starting football.

“I said, ‘No, sir,’ ” she recalls. “ ‘It’s probably cost-prohibitive.’ ” She suggested that instead they start a soccer team.

“I was here a year and knew that I had said the wrong thing,” Hickey says. “There was just a crying need for this campus to have an identity.” At the time the school had one intramural field and no rec center. “The longer I was here the more it seemed to me that the kids were not getting a full college experience.”

Coming from A&M, she knew what she was talking about. You can make the case that athletics is part of liberal arts. It’s almost an old-fashioned notion: Before college athletics was big business and college itself was about education for its own sake rather than economic advancement or narrow preprofessional training, sports were as much a part of a liberal arts education as music or great books. That Olympic ideal of a student may be a little lofty, but as far as a school is concerned, especially a big state school, you simply can’t have a well-rounded institution without a football program. The team’s role as a social and symbolic linchpin is hard to overstate.

Romo and Hickey knew that UTSA needed that sort of engine of enthusiasm, but first there was the matter of money. When Hickey first arrived, the entire athletics budget was $1.5 million. After the student body vote to double athletics fees, the rest was solicited from local supporters like Jimmy Cavender and Red McCombs.

McCombs refers to the team as a start-up, and for sure, it is like any other company, with multiple departments and levels of personnel. Purchasing and receiving. Laundry. Transportation. Even cheerleading and band, both of which expanded and got new directors in light of the increased size and expectations football brings. Seeing all of this come together over the past four years has provided UTSA with an unusual glimpse at the often overlooked details that go into fielding a football team. No other college sport brings with it as many infrastructure needs.

The biggest detail, however, is the coach, and for that UTSA can thank a footnote in San Antonio history: the USFL San Antonio Gunslingers, who played at Alamo Stadium in 1984 and 1985. A friend and former colleague of Coker’s who’d played on that Gunslinger team tipped him off about the job.

“He says, ‘Coach, UTSA is starting football. Were you aware of that?’ ” Coker recalls. “I said, ‘No, I didn’t know there was a UTSA.’ ” He called Hickey’s office and left a message.

Two months later, he had the job.

During his six years as head coach of Miami, Coker had a 60-15 record, with his 2002 squad falling one overtime pass interference call short of a second BCS trophy. But his time there ended after a troubled 2006 season that included an on-field brawl during a game against Florida International—unacceptable for a program with Miami’s thuggish reputation (though if Coker had gone 10-2 that season rather than 6-6, it would have been much less so). He and his wife, Dianna, remained in Florida as he settled into the ex-coach’s chair on ESPN’s college football broadcasts.

“He is the type of person who can handle what you have to do as a start-up,” says Hickey. “You know, having an office in a modular building? He handles that really well.”

Indeed, while Mack Brown’s headquarters boast Longhorn-hide accents and a picture-postcard window onto Royal-Memorial Stadium, the state’s only other national-championship-winning coach sits at a desk in what is basically a double-wide, nondescriptly tucked behind UTSA’s humanities building, with a distant view of Loop 1604. And while Coker’s team will spend its home games playing in a luxury-boxed stadium, its practice field is five miles from campus: the Northside Independent School District’s Dub Farris Stadium.

None of this bothers the 63-year-old Coker, who seems genuinely energized by the challenge of launching a new program. Avuncular and bald, he could pass for a professor if he ditched the Nike coach-wear. During the spring game, he blended in with his assistants on the field, just another guy in white pants, a blue UTSA shirt, and a cap (the latter covering up his most distinctive feature), lining up 10 yards behind the quarterback on every play so he could better read the player chemistry. “See if guys were in gripe mode,” he explains, “see if they feel sorry for themselves, are they competing.”

At Coker’s age, he probably wasn’t going to be a hot candidate for a seven-figure job opening, nor did he necessarily want to be. “It’s not a deal where I’ve still got all these mountains I’ve got to climb,” he says. “This mountain’s big enough. I didn’t have to do this. That’s a good position to be in.” Out on the Alamodome concourse that day, a few coeds got their picture taken at the season ticket table with a not-quite-full-size stand-up cutout of Coker. For now, he’s the face of the program in a recognizable but low-key way, a head coach with a flashy résumé but not a flashy personality, which probably suits a town where Tim Duncan and George Strait are the biggest stars.

Coker misses and doesn’t miss the big time: “Mack” and “Nick” (Saban, the University of Alabama head coach), as he calls them, may get the glory, but they also get the aggravation: crazy fan bases, intense media scrutiny, pampered NFL-bound players. “This program is about as pure as you’ll ever find, because we don’t have guys that are like, ‘Coach, after this year I’m going [pro],’ or, ‘Coach, I know you need me at right guard, but I’m really a left tackle because they make more money in the NFL,’ ” he says. Then he adds, with just a little smile, “Hopefully we do someday.”

UTSA’s first two recruiting classes include eighteen All-State players, a quarterback who transferred from Texas State, several transfers who gave up scholarships at other schools for the chance to walk on as a Roadrunner, and a lineman who played for San Antonio’s six-man team for homeschooled kids. Many football players choose schools like Baylor, Rice, or (until its recent dominance) TCU because they’re looking to stand out and want to help build something instead of just being plugged into a team that’s already elite. At UTSA, they’re really building.

“That’s been a big part of it, as far as kids that want to be here,” says Coker. “And they want to play for me. I say it with humility: Kids say, ‘Coach, I’d like a chance to play for you.’ That means a lot. Four years, five years, ten years from now it’ll be ‘Coach, this was the greatest experience I’ve ever had in my life.’ ”

So what will constitute success for UTSA football? “Number one is the kickoff on September 3 in the dome,” says Hickey. “There are a lot of people that thought this would never happen. But we’re not in this to lose.”

Nevertheless, nobody really expects anything out of UTSA for the first couple seasons. “I hope we win a few games,” said Chris Westbrook, a senior who came to the spring scrimmage with his friend and fellow Houston native Brian Elliott, both of them well-beered and outfitted in Rowdy “plush heads” (it’s a hat and a stuffed animal). “It would be nice for us to go .500.” Still, fans like Elliott have no illusions about the stakes. “You do have higher expectations than some other states’,” he said. “Because Texas football rules!”

UTSA’s 2011 schedule appears to have been engineered to let the program build its confidence. Four of the ten games are against Division II, III, or NAIA programs, so the blueprint is to win all of those and then take one or two against the remaining FCS (Football Championship Series, or what we used to call Division I-AA) opponents. Next year, things get tougher: The Roadrunners move up to the FBS (Football Bowl Series) level as a member of the Western Athletic Conference (as does I-35 rival Texas State). In addition to the WAC opponents, future seasons will include such teams as Oklahoma State, Virginia, Arizona, Houston, Rice, and Kansas State.

Following the lead of McCombs and Cavender, San Antonio’s business community has gotten on board: Coker says he was originally told that the athletics department would be content if it sold only 8 of the Alamodome’s corporate boxes; instead 32 out of 40 have been claimed. As of August 1, season ticket sales had surpassed eight thousand, so while the first game might be a novelty, the dome will not be packed each week, at least not yet. But with a single team to rally around, San Antonio could well be like the world’s biggest high school football town. Though its urban population has crept ahead of Dallas’s, its atmosphere and homeyness and sense of civic pride still feel more like Friday Night Lights’ fictional Dillon. It’s not hard to see the city taking up the Roadrunner cause. As with the Spurs, they will be San Antonio’s and San Antonio’s alone—something that’s not even true of the Longhorns and Austin. And unlike Rice, U of H, SMU, and TCU, the Roadrunners don’t have to compete with a pro team for the attention of the local media.

But UTSA also knows that it can look beyond San Antonio. Until now, there hasn’t been a Division I program south of San Marcos. Which gives the Roadrunners, at least in theory, a very wide market, including the equally fast-growing region of South Texas and the border. Winning over fans with prior allegiances will be the hard part. But Coker says he’s had a few people tell him, “Coach, I’m a Texas alum. I’ve got tickets to Texas, but I can’t go every weekend, so I’ll go to some of your games.”

And perhaps one day those fans will have to pick a side. After all, Hickey was at A&M for fifteen years, and UT athletics director DeLoss Dodds gave her her first major coaching job, at Kansas State, and also endorsed her strongly when she interviewed with UTSA. So when does Hickey plan to get her mentor on the phone to talk about scheduling?

She laughs. “Oh, DeLoss and I have not talked about this yet!” she says, before chuckling again. “That is, uh, probably down the road a bit. But how fun would that be for the Longhorns to be in the Alamodome?”

Until then, for a program that, prior to this month, had never played a single game and a city that has never really had a football team of its own, the Northeastern State Riverhawks will have to do. And they will do just fine. Even at the spring game, when only a few first-level sections on one sideline were occupied by fans, you could feel the players’ excitement. “I’ve never been in a stadium like this,” said defensive back Mark Waters, an El Paso native who transferred to UTSA as a walk-on but is now on scholarship for what will likely be his final season as a football player. “Never in my life.” And what did he imagine he might feel like on September 3, when the dome was full of people and he was making tackles in a game that actually counts?

“I think I might shed a tear,” he said. “I think I might shed a tear.”