This exclusive excerpt from Diana Finlay Hendricks’s Delbert McClinton: One of the Fortunate Few (December 6, Texas A&M University Press) revisits a time when students from the University of Texas were mingling with South Austin hippies and honky-tonk cowboys. Sure, the 1970s gave birth of the so-called progressive country scene, but it also marked the beginning of Austin’s blues scene—thanks, in part to Delbert McClinton.

Reproduced with permission from Texas A&M University Press

“It Ain’t What-cha Eat but the Way How You Chew It”: Progressive Country

In the mid-1970s, Austin was happening. I was playing down there a lot, and we were tired of Nashville. We packed up and moved. Austin had this scene going that worked for us. People wanted to hear original music. Hippies and cowboys came out to hear the same bands. And everyone got along. – Delbert McClinton

Progressive country. Redneck rock. Rhythm and blues. The 1970s were a coming of age for the Austin music scene. It wasn’t just about the music. Everyone was feeling a new sense of freedom. Texas politicians were hanging out backstage at concerts. A startup magazine called Texas Monthly was seeking young, hungry contributing writers. With new art, music, and literature, Austin was being called the Paris of the 1970s. Newspaper hacks were stretching their boundaries from journalism to literature, and gathering at such iconic Austin landmarks as Soap Creek Saloon, the Texas Chili Parlor, and of course, the Armadillo World Headquarters.

In November 1973, Jan Reid’s “The Coming of Redneck Hip” marked his first major feature in the pages of Texas Monthly. He chronicled this new country-rock hybrid sound that was coming out of Austin, and wrote of the migration of seasoned musicians into the capital city. As he told the story of the first financial music festival disaster that was the Dripping Springs Reunion music festival in 1972, he knew the people behind this new movement were on to something more. He introduced Armadillo World Headquarters owner Eddie Wilson to a broader audience than the young hippies and old cowboys who stood side by side in the old armory building-turned-music hall in Austin. Reid writes, “[Eddie] Wilson and his music business colleagues stress that any Austin music boom must remain localized.

“The creation of a music center in Austin would bring millions of dollars into the local economy, millions that would wind up in the pockets of Austin musicians, technicians, artists and publicists struggling to get by now. Even the environment would benefit. According to Wilson the music industry, unlike others that a growing Austin might attract, ‘doesn’t pollute and it doesn’t get in the way visually; about fifty million dollars could be put into the Austin music business and remain invisible.’ The stage has been set very nicely, so why not continue? Thus the music businessmen proceed, caution thrown to the winds.”

In The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock, a book that grew from that magazine article, Reid writes, “A number of musicians who were already battered and bruised by the major music centers began to settle in Austin. They were songwriters and singers of varied experience and potential, but they were good enough to land recording contracts with major companies.” Reid adds that the newly established Armadillo World Headquarters, a counter-culture honkytonk with adequate floor space but almost no furnishings became a community center for artistic expression, hosting legendary acts, and new bands from around the country.

The originators of the Armadillo World Headquarters were a young beer distributor, Eddie Wilson; an entertainment lawyer, Mike Tolleson; and a graphic artist named Jim Franklin. They rented an old airplane hangar-like armory building that had been sitting vacant for nearly a decade, and the Armadillo was soon in a league with San Francisco and New York music venues. Jan Reid writes, “Suddenly, Austin swarmed with singer-songwriters who looked like bearded hippies but wore cowboy hats and recruited fiddle and steel guitar players.”

Delbert and Donna Sue didn’t live in Austin for long, but their time in Austin coincided with a major shift in commercial music. Nashville, Tennessee, the traditional home of the country music industry, had become too confining for artists who wanted to do more than copy the hits of the day. This was not the first time differing opinions had threatened the Nashville dominance of the genre.

In the mid- to late-1950s, Buck Owens and Merle Haggard had established a new country scene on the West Coast that came to be known as the “Bakersfield Sound.” Renowned radio personality Bill Mack says, “This was a direct reaction to the slick, orchestrated Nashville sounds of the time. While Nashville producers were muting rhythm sections and smoothing vocals into an easy listening mode, Buck Owens teamed with Don Rich and brought that twangy Fender guitar sound to the front of the record mix. Merle Haggard was celebrating his rough voice, and singing of prisons and swinging doors, while in Nashville, Ray Price was crooning ‘Danny Boy.’”

Commonly referred to as the “Nashville Sound” and “California Country,” these two music scenes would compete head-on for audiences, even hosting competing national awards shows, “The Country Music Awards” in Nashville and “The Academy of Country Music Awards” in California. Bill Mack continues, “The Nashville country music industry had worked long and hard to develop a legitimate genre. They were not going to allow it to be taken over by rock and roll drums and rowdy bands. The new sophistication that had finally found its way into country music allowed orchestrated country hits to cross-over into the pop charts, but the Nashville country music industry was very protective of its newly created sound, and did not welcome organic music that sounded untrained and unpolished.”

Fast-forward ten years and fifteen hundred miles from Bakersfield to Austin. Another group of rebels had grown tired of—or been kicked to the curb in—Nashville. They want the freedom to create their own sounds and focus on original music. Willie Nelson has often been credited for starting this new culture in Austin, and it quickly caught on.

This new Austin music scene will be vital to the Delbert McClinton story because Austin was not only a melting pot for “outlaw” musicians but also a revival for singer-songwriters and a renaissance for blues music. While Delbert is quick to say he wasn’t really a part of that progressive country scene, his time in Austin was not to be overlooked.

Texas writer Joe Nick Patoski says, “Delbert was a minor player in the progressive country scene, but a major piece of the blues awakening that was happening in Austin. He was playing that Texas circuit: Houston, Lubbock, Dallas, Fort Worth, Austin, and he had a sound that was working for him. His music showed me that the thin line separating R&B from country and western was real fuzzy. Most people can’t pull that off. However, a good artist can mix that up. And Delbert was doing that. He was mixing up sound stereotypes with that hard driving blues beat and a fiddle, doing good songs his way. Delbert was making something that hippies elsewhere would consider uncool. But, where he was coming from, it was more than cool. It was authentic.”

Another Texas native, Willie Nelson, was tired of the limitations of the Nashville music industry expectations, and hungry to stretch his creativity. In the definitive biography, An Epic Life: Willie Nelson, Patoski writes, “His first concept album, Yesterday’s Wine, marked the beginning of the end of Willie’s relationship with RCA. The label pressed up the standard ten thousand copies and let nature take its course. Promotion behind Willie Nelson’s albums had historically been non-existent. Nothing had changed, and the situation would remain the same for the three RCA albums that followed, before his ties with RCA were severed.”

Another Texas native, Willie Nelson, was tired of the limitations of the Nashville music industry expectations, and hungry to stretch his creativity. In the definitive biography, An Epic Life: Willie Nelson, Patoski writes, “His first concept album, Yesterday’s Wine, marked the beginning of the end of Willie’s relationship with RCA. The label pressed up the standard ten thousand copies and let nature take its course. Promotion behind Willie Nelson’s albums had historically been non-existent. Nothing had changed, and the situation would remain the same for the three RCA albums that followed, before his ties with RCA were severed.”

This was business as usual in Nashville. As Patoski writes, “Chet Atkins [guitar virtuoso and head of RCA Records] may have been a picker’s picker. But as a producer and label chief, he stuck to a formula.”

This was an all-too-familiar story for Delbert McClinton, and other singer-songwriters who sought to be more than craftsmen cranking out a product in the Nashville music factories.

While Patoski credits Atkins with keeping country music alive when rock ‘n’ roll took over the sales bins, “There was no way he was going to have hits on all the acts he produced, and Willie was proof,” he said.

Songwriter Hank Cochran said, “The thing with Willie is they wanted him to tell them what he was gonna do in the studio; and he didn’t know what he was gonna do until he got into the studio.”

Delbert echoes that characteristic. He says, “I am hell-bent on getting live vocals. I want that sound. You lose the spontaneity, which is the truth in music. A mistake doesn’t matter. There’s a southwestern Indian tribe that purposely puts a flaw in every blanket they make to show the imperfection of mankind. I feel the same way about music. You know, you can polish something till it don’t shine.”

Austin welcomed originality, and this new genre reveled in spontaneity and the rough edges of live music. Joe Ely talks about Austin in the mid-1970s: “Everyone was talking about progressive country. The word got out that Austin was a good place to live, with lots of places to play. Rent was cheap and old houses were plentiful. You didn’t have to hustle to make a living. Musicians could pitch in and get a house together and start a band and make a little money. And, if you had a girlfriend, you could actually sometimes pay the rent.”

Joe adds, “There were about twenty clubs in Austin that featured live music. There was a happening blues scene on the east side. And a strong conjunto, Tex-Mex scene, and cowboy bars like the Broken Spoke and the Split Rail.”

Today, many of the people who were at the center of the progressive country scene still consider the title deceptive. “Progressive country was the silliest name,” Joe says. “It was much bigger than country. But, I think the people who were trying to figure out how to market it decided that they had to call it something so they could herd it up and sell it. And Delbert and I both got lumped into that for a while.”

What was actually happening in Austin in the 1970s was bigger than one genre. It was blues, rock, country, Tex-Mex, zydeco, and folk. While music writers were trying to get their heads around this new free-for-all genre, and debating what to call it, an undercurrent of the blues was making a huge impact.

Delbert explains, “Everyone was putting on a cowboy hat or a bandana around their neck. Willie brought it on in 1972 with the Dripping Springs Reunion. And that scene was all about the musicians. The musicians were getting the perks. It was a real coming together. It wasn’t about the business, it was about the music. Artists were starting to sing the songs that they wrote. It was an exciting time for me.”

He adds, “The blues scene was not as much of a coming together. It was a completely different atmospheric situation. It was something that you either are or you aren’t. I remember going on a blues cruise early on, and all the musicians had The Look. They were wearing black pants, black shoes, black ties, black hats, and I thought it comical to see these guys dressed like that, walking on the beaches of St. Thomas. And they were finding a groove. But it was not as flamboyant, or as much of a scene as progressive country. Stevie [Ray Vaughan] made it happen. The Thunderbirds certainly did. At that time in Austin, all of a sudden this new music was exploding. The Thunderbirds were a white band playing blues as well as anybody ever did. It was a time of spreading good, new music every which way.”

Musicologist Travis Stimeling writes, “a generation of young Texans redefined what it mean to be Texan in a countercultural age by claiming ownership of distinctly Texan forms of expressive culture, including not only music, but also fashion, language and art.”

Joe Ely says, “All of these Texas organic musical styles were coming together. In other towns, musics were not mixing a lot. Mexican bands were in certain places, and honkytonk bands were playing somewhere else, and blues bands were in another club. But in Austin, all of this music came together.

“Something happened in the 1970s. You would walk into a bar and see San Antonio’s West Side Horns jamming with the blues guys from Dallas. Soap Creek Saloon was a good example. They booked as much great blues as they did great country. They would have Doug Sahm and Delbert McClinton and Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Paul Ray and the Cobras, and Freda and the Firedogs and Asleep at the Wheel. It was like heaven.

“Delbert played this perfect combination of blues and country. It was a natural blend of the kind of music that started in Texas with such a rich history of Blind Lemon Jefferson, Mance Lipscomb, and Lightnin’ [Hopkins]. Delbert was mixing up rocking blues and adding a fiddle and hitting those harmonica solos. Something this interesting had not been done before. Anything goes. No rules. And we were in the middle of it.”

Students from the University of Texas were mingling with South Austin hippies, and honky-tonk cowboys. The names were as varied as the description of the music: western beat, outlaw music, redneck rock, progressive country, cosmic cowboys. By any name, it was new and different and didn’t quite fit in any of the standard record bins.

Delbert adds, “Those days in Austin were such an awakening for me. The whole integration thing was going on, and people were getting it. It was a time of no precedents, you did what you felt, and it’s still exciting to talk about.”

Joe Nick Patoski explains, “Delbert was a big part of the birth of Americana music. He could take that old country R&B that he loved most, and modernize it, paying loyal attention to the original intent. Doug [Sahm] did it too. They took that traditional American, traditional Texas music and did not bastardize it. They stayed faithful and true to the roots as they built on that foundation.”

Texas electric blues singer and music historian Angela Strehli went to Austin to attend the University of Texas. She earned a degree in sociology and Spanish, and immediately began to play music around town. “Out on the east side edge of town, a little bar called Alexander’s Place had these great Sunday afternoon outdoor concerts with barbecue. It was one of the best gigs a person could ever have. Clifford Antone was a big blues fan who had come to UT from Port Arthur, and was on a mission to introduce the world to blues music,” she said.

She added, “We had a lot of support from black people who loved blues music and saw it disappearing from the radio. For young people, blues was the past, the older generation. They wanted to do their own thing—disco, soul, rock. It was completely understandable. As it turned out, we were filling a gap and this important music stayed relevant and was passed down.”

At the time, blues was way underground, according to Angela. “It wasn’t hip, but we knew it was important. Radio wasn’t interested. But Clifford Antone was.”

Angela added, “Clifford wanted to open a blues club in Austin on the west side of Interstate 35. He was convinced that if the university students and other people who didn’t have access to the east side clubs could hear the blues masters, it would catch on, and they would understand what we were trying to do.

“As a musician, I wanted to do it. We would have a chance to be on a big stage, opening for our heroes. So, we opened Antone’s in 1975. It was one of the first music clubs on Sixth Street. This was Sixth Street long before it became a tourist attraction. There were a bunch of winos wandering the streets and old empty buildings. Jimmie Vaughan and the Fabulous Thunderbirds were sort of the house band. And we could get these legendary blues players to come down from Chicago and play with the house band, saving the expense of having to pay for their bands to come to town. And of course we had a regular rotation of Paul Ray, Stevie Ray, Delbert, Marcia Ball, and others. We had a couple of exceptions to the ‘seven nights a week blues club,’ with Asleep at the Wheel and Joe Ely, but it worked. A lot of people who had never heard blues before came out and loved what they heard, and loved Antone’s.”

Grammy winner Marcia Ball had graduated from her Freda and the Firedogs band to a solo career in 1974. She says, “We had good clubs in Austin then: the One-Knight, Alexander’s, Soap Creek Saloon, the Armadillo World Headquarters. And we could play somewhere just about every night. I called that time the progressive country scare, as people were trying to dissect and de ne what we were doing. We didn’t even know, ourselves.

“But blues was coming on strong to new audiences. I started seeing Delbert at Soap Creek. I remember that even before he started filling clubs, he was playing my kind of music. He was absolutely playing the music I loved. I would go out and dance the night away.

“Except for a short time when he and Donna Sue lived here, Delbert was coming and going, and had hits—or we thought he did. His venues got bigger and his crowds got bigger, and I was still a fan in the audience. I still am.

“Delbert and Doug were stars to us. We weren’t paying much attention to what the rest of the world was saying about us, but they had a complete unerring sense of what was happening, and what was going to happen right here. All of a sudden, all the hip- pies were pulling their Levi’s and boots and hats out of the closet and coming out to hear our music.”

Marcia recognizes the importance of that time in Austin: “When Antone’s opened in 1975, that really created a scene for us. It overlapped with the Armadillo and Soap Creek. It was a heyday for live music. There was something great happening every night. Soap Creek would bring in Professor Longhair, the Armadillo brought in everybody, and Antone’s became the blues scene of Austin. We were very fortunate to have all that music handed to us, to have the opportunity to play with, and to become lifelong friends with, some of our heroes.

“I made a transition from country to blues between 1975 and 1980. I went solo. I had been moving in the direction of R&B roots. I knew that was where I needed to go. I always felt that country music and rock and roll would age you out. But with blues, the older you got the more revered you are.”

Jan Reid talks about the budding Austin music scene: “It was in April of 1973. Willie was playing the Armadillo World Headquarters with his full band for the first time. No one knew how the concert would go. With clouds of marijuana smoke always pungent in the place, hippies mingled with Willie’s redneck fans. But any hostility between the two audiences evaporated as they were swept up in the spell of Willie’s jazz-inflected singing and his playing of a battered Martin guitar.”

Reid explains that while Willie had discovered his taste for marijuana to take the edge off, and he was perhaps the first country artist to grow a beard and long hair, his real revolt was against the industry, the contracts, arrangements, and session bands that had been forced on him.

Delbert was in the same boat. He had his hopes dashed with two recording companies, but music was his passion and Austin welcomed his art. Reid writes: “[Delbert] sang rhythm and blues like the masters. Fats Domino’s ‘Blue Monday,’ and James Brown’s ‘Please, Please, Please.’ ABC Records went out of business and progressive country started fading; when fashion in Austin music changed from country to blues, he made the transition with ease. Blues was where he started.

“Emmylou Harris recorded his fine ode to failure out West, ‘Two More Bottles of Wine.’ Delbert was swapping lyrics and interpretations with blues diva Etta James. The title song of his fifth record, Love Rustler had cracked Billboard’s Top 100—just in time for his record company to go broke.

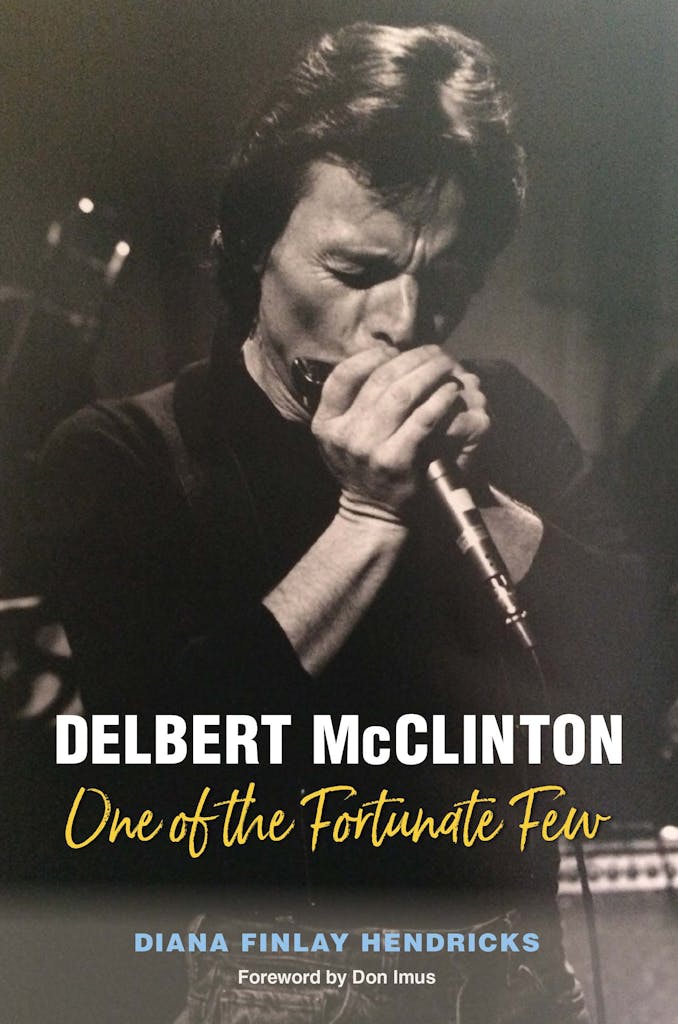

“Still, people in Austin were standing in lines to get in to see him at the Soap Creek Saloon. With a mop of auburn hair and a broad expressive mouth—‘Great lips,’ said a woman who used to date him—he moved through the Austin scene like an Irishman out of central casting.

“He could sing and make the harmonica wail, and he knew all the moves. ‘How you, pal?’ he’d say with a nod to a fan as he sauntered outside on a band break, wearing jeans and loafers and a leather sport coat, lightly carrying a shot glass of [tequila]. Delbert was the consummate, cool, white honky-tonker.”

Delbert has always maintained his audience because he is, first and foremost, a live act. Peter Guralnick writes, “In some ways, none of the albums, with the possible exception of Victim, has done justice to his talent, simply because they lack the directness, the dangerous incandescence of a live set.”

However, the records have always remained close to Delbert’s vision. He explained to Guralnick that the music he grew up with was “raw and unpolished, maybe, but that shit was not mediocre. You might talk to a technician and he might tell you how pitiful the mix was, and all that—but goddamn, but goddamn boy. You were hearing somebody’s heart beat.

“And when you’d get right down to it, you can burn all the machines and shit, and hand somebody a guitar, and that’s what it gets down to. You can either move them or you can’t. And it don’t have nothing to do with turning knobs. And that, to me, is what I want to keep alive.”

In 1974, Delbert was playing on the road, and Donna Sue and Clay were living in Austin. Monty had turned fourteen and was allowed to choose which parent with whom he wanted to live. “He was ready to come live with us. He was looking for better ground, and I was so glad to have him. I had missed so much of his childhood. He was a good kid. He was not that good in school, but Donna Sue tried hard to help him.”

By 1976, Donna Sue wanted to move back home to Fort Worth. Things were not going well with this marriage, but Delbert was hell-bent on trying to make her happy, and to make it work. So, he moved their trailer back to Fort Worth, where they parked it behind her good friend, Priscilla Davis’s home, commonly referred to as the Davis Mansion. They lived there temporarily, while she set out shopping for a permanent home. Delbert and Donna Sue would soon find themselves brushing all too close to one of the most infamous murder mysteries in American history.

“Clay was a toddler,” Delbert says, “and we had moved out of the trailer and into the Davis Mansion. Donna Sue and Priscilla were friends. I was either in Austin or on the road most of the time, so Donna Sue and Clay moved out of the trailer and into the big house with Priscilla. When I was in Fort Worth, I would stay there.”

Priscilla was married to one of the wealthiest men in Fort Worth, T. Cullen Davis. Davis had owned Stratoflex, one of the hellish companies Delbert had worked for back in the early 1960s, but it was the friendship between Donna Sue and Priscilla that brought the McClintons to the Davis Mansion. Gary Cartwright wrote about the murders in Blood Will Tell, chronicling this “chilling story of sex, drugs, money, murder and mayhem, Texas-style.”

As Cartwright summarizes the story: “On the day his oil tycoon father died, T. Cullen Davis wed flashy, twice-married Priscilla Lee Wilborn, dismissed by Fort Worth Society as ‘that platinum hussy with the silicone implants, and the RICH BITCH diamond studded necklace.’

“Six violent years later, Priscilla filed for divorce. On August 2, 1976, the eve of the divorce trial, Priscilla and her lover, Stan Farr, returned home to a hailstorm of bullets. Farr and Priscilla’s daughter Andrea died. Priscilla, shot in the chest, escaped—and clearly identified T. Cullen Davis as the black-clad assassin.”

Delbert recalls the friendship between Donna Sue and Priscilla, and how much they enjoyed the club scene. He describes the Davis Mansion, “It was huge, and filled with all kinds of antiques. Monty was out of school and had moved out on his own. Donna Sue and I would run across the highly polished beautiful wood floors in our socks, and see how far we could slide.”

Former Rondels manager and car dealer Jerry Conditt knew Cullen Davis well. He recalls many of the details of that mystery: “Fort Worth was such a small town in those days. I knew Cullen real well,” he says, “and, yes, I knew Priscilla. She had been married to Jack Wilborn, another car dealer in Fort Worth. Jack played blackjack with my dad just about every day. He was the nicest guy in the world. It was his daughter, Andrea, who was killed that night.

“Priscilla was—well—promiscuous. And at that time, I think Cullen was making about a million dollars a week. I could tell you a lot of stories about him, but we are already getting off track.

“Anyway, Priscilla took up with Cullen, and it was like water and oil. They were fighting all the time. Fort Worth was a small town, and we were all still friends. Delbert’s wife, Donna Sue, was a lot like Priscilla. Donna Sue was a trust-fund baby, and had a little money. She always wanted to be center-stage. She liked to be the center of attention. Sometimes she would run up on stage when Delbert was singing. It was just a little off.

“I think it was a Sunday, the day before the murders happened. I had a fifty-foot cabin cruiser at the time. I called Cullen and told him we were going out the next night on my boat. He wanted to meet us and go out for the night. Then later on the next day, he called me back and said something had come up, he had a change of plans, and wasn’t going to be able to make it. And that was the night the murders happened. I am just glad Donna Sue and Delbert were not still living out there.”

Delbert adds, “Donna Sue had found a house in Fort Worth, about two weeks before the murders and had moved out. The night of the murders, I was in San Antonio rehearsing with some new guys. Donna Sue was at the new house in Fort Worth. She had gone by the mansion that night and didn’t see any lights on so she just went on back home. I was heading back to Fort Worth the next day when I heard that it had all happened. We knew most of those people, and there were some characters of very questionable reputation out there. There was a lot of bad stuff happening out there. I was just glad we were out of there before it happened.”

Another chapter of Delbert’s life was soon to end. As the 1980s grew near, the progressive movement was waning. In its place, the urban cowboy movement was taking over country music. Denim and diamonds would soon replace bandana headbands and faded jeans.

On September 12, 1978, Esquire published Aaron Latham’s “The Ballad of the Urban Cowboy: America’s Search for True Grit.” It was a story about the new country music scene down in Houston.

Delbert was making some changes as well. In 1978, two years after ABC went out of business, he played some artist showcases in Nashville, and was picked up by Capricorn Records. This business of music was rough, but Delbert McClinton was getting his Second Wind.