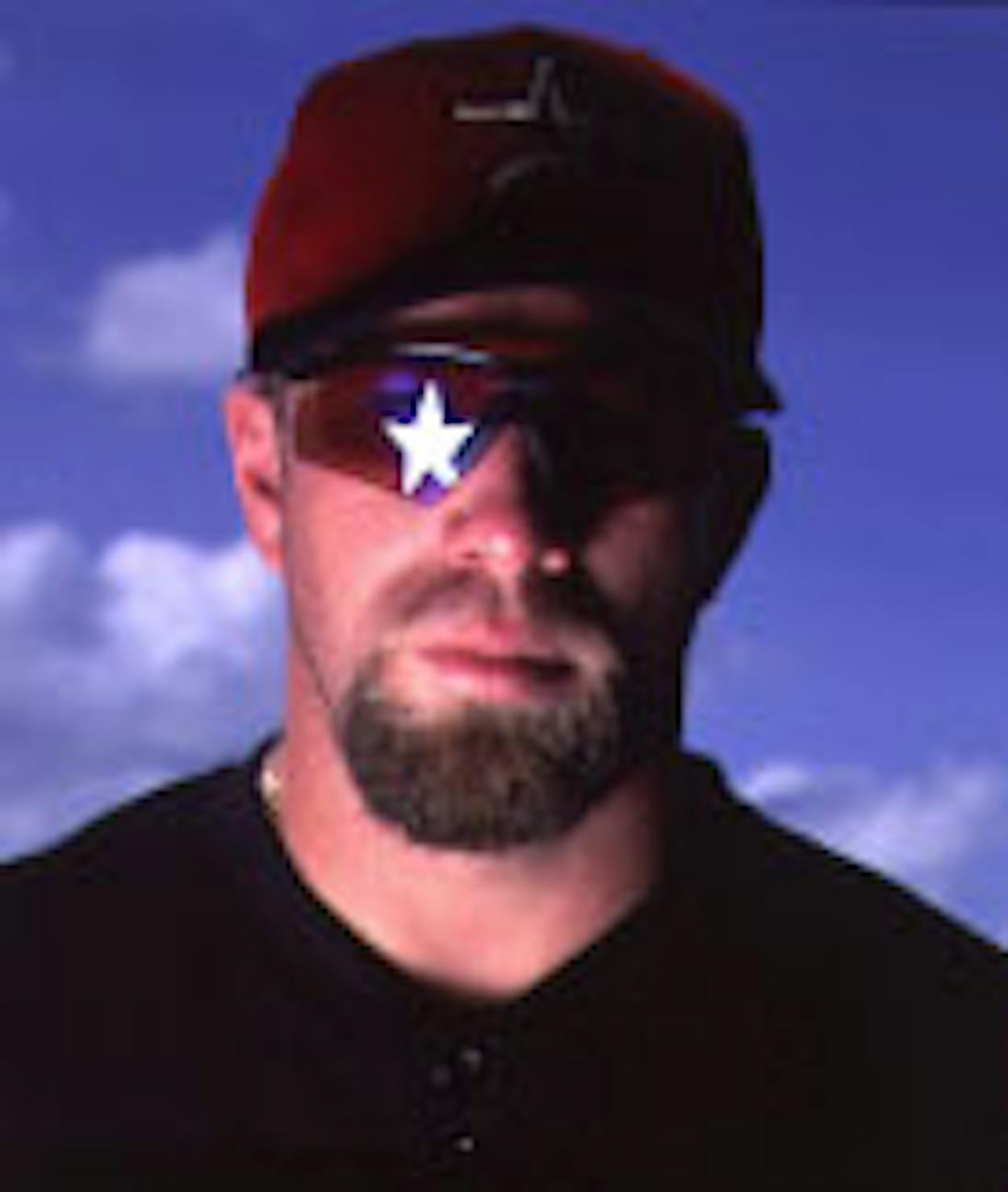

In honor of opening day 2001, here’s a quiz for Astros and Rangers fans. Can you name the major league ballplayer who last year hit more than 45 home runs, collected more than 100 RBIs, and scored more than 150 times—a feat equaled in the history of baseball only by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, and Jimmie Foxx? The answer, as any die-hard Astros fan can tell you, is Houston’s first baseman Jeff Bagwell. Though the Astros had a rotten season last year, finishing 23 games out of first place, Bagwell treated pitchers like they were in Little League. He pounded 47 homers, drove in 132 runs, and scored 152 times.

What he did not do, however, was sign the richest contract in the history of professional sports last December for an unholy $252 million over ten years. That honor belongs to newly signed Texas Rangers shortstop Alex Rodriguez, the man known as A-Rod. Not that Bagwell, who signed a five-year, $85 million contract extension signed a week after A-Rod’s deal was announced, is going to have trouble paying his phone bills. He is among the best-paid players in the game. But over the next five years of the extension, A-Rod will earn $25 million more than Bagwell. Even in the hyperinflated financial world of Major League Baseball, that’s not chump change.

But it begs an obvious question: Is A-Rod that much better than Bagwell? The answer, with apologies in advance to Rangers’ fans, is no way, partner, not even if Rodriguez could pitch relief. Any way you cut it, in spite of the flood of optimism that has accompanied A-Rod’s anointment as the savior of the Rangers, Bagwell is a better deal. He is not just cheaper by a country mile. He is actually, stat for stat, a better player. And I have the numbers that prove it.

The first and most obvious difference between the two is that Bagwell is a better hitter. His astounding season at the plate last year—one of the most remarkable in the history of the game—was merely the latest example. Though A-Rod, who had his own career year, squeaked by Bagwell in batting average (.316 to .310), and tied him in RBIs, Bagwell dominates almost every other category. He hit more home runs (47 to 41) and scored more runs (152 to 134). He had more hits (183 to 175) and total bases (363 to 336) and had a higher slugging percentage (.615 to .606). Bagwell also played in more games (159 to 148).

A look at their stats over the past five seasons gives even more of an edge to Bagwell. From the 1996 season, the first in which Rodriguez played more than one hundred games, through 2000, he has homered 184 times; Bagwell has done it 197 times. Rodriguez has driven in 574 RBIs; Bagwell has banged in 624. Bagwell also leads in slugging percentage, .585 to .574, as well as runs scored, .639 to .608. Though Rodriguez has a slim lead over Bagwell in career slugging percentage (.561 to .552) and batting average (.309 to .305), Bagwell has a lifetime on-base percentage of .417, far ahead of Rodriguez’s .374. Both strike out at the same rate (about 19 percent of the time), though Bagwell is far ahead in drawing walks. Over the past five seasons, Bagwell has taken a free pass 627 times. Rodriguez has done so only 301 times.

Bagwell’s edge in hitting over A-Rod is all the more significant since their teams live and die by their production at the plate. Both the Astros and the Rangers have won their divisions three times since 1996, but neither has advanced past the first round of the playoffs. Last year the Astros had the worst combined earned run average in the National League, at 5.41; the Rangers had the worst in all of baseball, at 5.52. In the absence of good pitching, it will be run production that gets the Rangers and Astros past the first round. So Bagwell’s advantage over the past five years in home runs, runs scored, RBIs, and slugging percentage looms even larger.

Of course, one of the reasons that A-Rod received such a huge deal is his youth. At 25, he’s seven years younger than Bagwell. But Bagwell leads in durability too. In the past five seasons, A-Rod has played in 725 games. Bagwell has played in 792. Over the past two seasons, Bagwell has played in 44 more games than Rodriguez, and he has played in every regular season game four times in his career. Rodriguez has done so only once. And so far age hasn’t slowed Bagwell down. Last year he had more hits and scored more runs in a season than ever before, and he set the Astros’ single-season home run record. Whose record did he break? His own, when he hit 43 in 1997.

In a comparison of their defensive worth, A-Rod fares somewhat better, in part because he is a shortstop, a more critical position than first base. Indeed, some would say that it’s useless to compare a first baseman with a shortstop in terms of worth. Statistics guru Bill James, who has written a number of books about baseball, disagrees. “The distinction between a shortstop and a first baseman is not really a troublesome one,” he says. “Rodriguez has positional value in that he plays shortstop, but Bagwell is a better hitter. That more or less balances out.” Well, perhaps not quite, as you can see by comparing each player with other players at his position. Bagwell’s career fielding percentage of .993 ranks him tenth among all active first basemen. A-Rod’s .970 ranks him fifteenth among all active shortstops. My point: Though you would expect a shortstop to have a worse fielding percentage than a first baseman, over time Bagwell has proven himself to be better at his postion than A-Rod is at his. Yes, Rodriguez is a great shortstop, but he is no better among his peers (and even a little bit worse) than Bagwell is among his.

But let’s face it, part of what makes a player special is that he shows loyalty to his team. Can you imagine Joe DiMaggio playing in anything other than pinstripes? Or Carl Yastrzemski not calling Fenway Park home? Fairly or not, A-Rod is seen as an opportunist who signed with a club that needs a star pitcher, not another slugger. Rodriguez will become the de facto leader of the Rangers, but fans will turn on him quickly if he doesn’t prove himself. Bagwell, meanwhile, has earned his leadership of the Astros. That’s not to say that he put his team far above salary. He didn’t. Before A-Rod signed with Texas, Bagwell was finishing up his own contract negotiations with the Astros and had agreed to be paid about $16.8 million a year. When he heard about A-Rod’s salary, he asked for $17 million. Still, riots might have broken out if the team hadn’t re-signed its best player, particularly after the disastrous season Houston had last year. “It was a matter of credibility,” says Fran Blinebury, a sports columnist for the Houston Chronicle. “If they didn’t sign Bagwell, you’d have had someone climb up and knock down that choo-choo train at Enron Field.”

Unlike the team-hopping Rodriguez, Bagwell wanted to stay put, though there’s little doubt that he could have received a larger salary elsewhere. “If Bagwell had wanted to push it, if he had wanted to go out on the open market, could he have gotten twenty million a year? Probably,” says Blinebury. “But there’s an allegiance there for him. The Astros have never had one of their great players retire in their uniform.”

From the Astros’ point of view, it was also the logical extension of an astonishingly consistent career. As a rookie in 1991, Bagwell’s impact on the struggling team was immediate. Though the Astros finished in last place, Bagwell led the team with 15 homers, 82 RBIs, and a slugging percentage of .437. He was named National League Rookie of the Year, the club’s most valuable player, and Baseball America‘s Major League Rookie of the Year. Since then he has won almost every award available: He was the National League MVP in 1994, he is a four-time All-Star, and he has been named Astros MVP more times than any other player. Along with teammate and friend Craig Biggio, who has played with Houston since 1988, Bagwell has become a consummate team player. His new contract should guarantee that the greatest Astro in history will retire in an Astros uniform. “One of the things that some players pride themselves on is playing for one team, and that’s a very exclusive club,” says Barry Axelrod, Bagwell’s agent. “We looked at it, and there are players like Tony Gwynn, Barry Larkin, Cal Ripken, Craig Biggio, Tom Glavine, and Bagwell. It’s rare to play your whole career on the same team.”

The lingering question, then, is why, in view of such statistical truths, Rangers owner Tom Hicks paid so much more for A-Rod than the Astros paid for Bagwell. Indeed Yankee shortstop Derek Jeter’s ten-year, $189 million contract, a small notch up from Bagwell’s pay in annual terms, offers an even better benchmark of just how bad the A-Rod deal was—or how good the Bagwell deal was, depending on your point of view. Though Jeter doesn’t have the offensive numbers that Bagwell or Rodriguez has, he is a leader on a team that has won four world championships in the past five years. Last season he was the MVP of both the All-Star Game and the World Series, the first player ever to win those awards in the same season. For all that, his new contract is $63 million less than Rodriguez.

Among those who don’t like A-Rod’s deal is, predictably, Axelrod. “The A-Rod deal surprised me, especially when you hear what the next highest offers were,” he says. “Supposedly his next best offer was seven years at $128 million from Atlanta. Then five at $95 million from Seattle. Tom Hicks paid him double what anyone else was offering. And why? I don’t know, other than he can.”

Well, for one thing it has paid off in the short term—the Rangers haven’t had this much attention since Nolan Ryan retired. Yet Bagwell may have the last at-bat. Houston had a much stronger off-season than Texas did. The Astros picked up All-Star catcher Brad Ausmus and a reliable set-up man in Doug Brocail. If right-hander Shane Reynolds and closer Billy Wagner fully recover from last year’s injuries, the Astros pitching staff could go a game or two without giving up a home run. As for the Rangers, their starting rotation returns intact—and that’s not a good thing. A pennant flying over Enron Field would be an even stronger argument in Bagwell’s favor.

Fans will get the opportunity to judge this for themselves, in person. For the first time ever, the Rangers and the Astros will play each other during the regular season. When that happens, Bagwell will have the chance to show fans at the Ballpark in Arlington exactly what an $85 million first baseman can do.