This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Remember the Hardy Boys books?

In an era of accelerating change when conversations turn to future shock and generation gaps, some things stay the same—or seem to. One of my warmest recollections of childhood in the early Fifties is the series of suspenseful yarns about the adventures of Frank and Joe Hardy, fictional teenage sons of an eminent if somewhat incompetent private eye. The same series entertained preadolescent youngsters as long ago as the 1930s. Most of the books are still in print, avidly devoured by the children of the Seventies. Through a Great Depression, three wars, and the onset of shortages, not much else has lasted so well.

My favorite was always Number 20: The Mystery of the Flying Express. Much of the action (pursuit of spies: this was copyrighted in 1941) revolves around a crack transcontinental passenger train with observation cars, “luxurious sleepers,” long shiny coaches, and a locomotive capable of producing a “thunderous roar”: the Flying Express was nothing less than “the great giant of the rails,” and its presence suffused the commonplace narrative with an exotic distortion of time and distance.

Not long ago I ran across an up-to-date copy on sale in a Corpus Christi bookstore. This is how the Flying Express was described:

The ship’s sleek hull had enclosed cabins forward and aft, and a rakish pilot’s bridge. The windshields of the wheelhouse looked out over a metal deck. This forward deck obviously was not for passengers. The rear deck was slightly lower and guarded by white pipe railing.

“Quite a boat,” Frank said admiringly.

Same series, same title, but the magnificent train was gone. In its place was a “shiny white fiberglass vessel” providing hydrofoil service across a bay. A new copyright dated 1970 indicated that the publishers had simply concluded that a railroad train carrying passengers would likely be as unfamiliar as a yak caravan to their ten-year-old American readers. Accordingly they had ordered the book rewritten.

In 1970 their decision must have seemed perfectly sensible. Rail passenger service had deteriorated all across the country. Railroad executives, eager to discard this bothersome interference with their more-profitable freight business, scornfully compared passenger trains to stagecoaches and steamships. From a peak in 1929, when they transported 77 percent of intercity travelers, the railroads’ share of the common carrier market had been sharply eroded by airplanes and buses. A sudden burst of traffic during and immediately after World War II proved only temporary. The Texas postwar experience was as typical as any: in 1947, 8.5 million passengers produced $28.2 million worth of revenue in Texas; by 1970 there were only 371,000 passengers and $2.5 million in revenue. Blame for the decline has been placed on hostile railroad management (by travelers) and on the changing tastes of the traveling public (by railroad management); but its reality was indisputable. More than half the 20,000 passenger trains running in 1929 had disappeared by 1950. By 1970, fewer than 450 remained, and only the reluctance of state regulatory agencies and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) prevented the discontinuance of most of these. The straight-line thinkers who published the Hardy Boys saw an obsolete book on their hands.

Amtrak, the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, came into existence on May 1, 1971, largely because it offered something that both the traveling public and the railroad companies wanted. The public wanted passenger operations taken away from railroad company management—many of whom were dedicated to making life miserable enough for passengers to drive them away from the trains altogether, thereby providing a legal justification for discontinuing service. Amtrak offered the encouraging prospect of a friendly, quasi-public corporation to run the trains and integrate them into a unified network.

The railroad companies wanted to rid themselves of passenger service as quickly as possible. Amtrak provided a way to do this without the need to deal with skeptical state regulators and the ICC on a tedious, case-by-case basis. The Rail Passenger Service Act that created the new corporation did more than designate a limited number of passenger routes for inclusion in Amtrak’s basic nationwide system; at the instigation of certain railroad companies, the law was phrased in a manner that actually deprived the member railroads of legal authority to operate intercity passenger trains of their own. Thus, if a railroad “joined” Amtrak (and all but four intercity passenger lines did), the company granted Amtrak the right to operate a few selected trains across its tracks and simultaneously stripped itself of the right to operate any others. To the railroads the idea was immensely attractive, like Br’er Rabbit’s briar patch. More than 200 passenger trains were left unprotected. The inauguration of Amtrak on May 1, 1971, was accompanied by history’s greatest transportation bloodbath. By the next morning an eerie calm had descended upon the member railroads’ tracks. Only Amtrak’s sixteen chosen routes escaped the carnage.

If this compromise was an idea whose time had come, it assuredly was not an idea that either side viewed as a permanent solution. Consumer groups like the National Association of Railroad Passengers promptly agitated for the inclusion of additional routes. And the railroads, particularly those like Southern Pacific (SP) that have been most consistently antagonistic to passenger service, treated Amtrak as a temporary annoyance to be tolerated for a few months until it collapsed of its own dead weight. Southern Pacific President Benjamin Biaggini declared: “There is no market for long-distance, intercity passenger transportation by rail. People just won’t ride it . . . I think Amtrak’s function should be to preside over an orderly shrinkage of rail passenger service.” He said “shrinkage,” but most passengers knew he meant “termination.”

To the astonishment of the railroad doomsayers, however, Amtrak did not die. Political support in Congress propped it up for a while. And the public refused to abandon the remaining trains. On practically every line, ridership increased. The average traffic count in August at El Paso on Amtrak’s Houston-to-Los Angeles train, for example, rose from 600 in 1971 to 1900 in 1972 to 2250 in 1973. Then, when the gasoline shortage hit in November 1973, passengers flooded ticket counters in numbers far exceeding Amtrak’s most optimistic projections. Many remained loyal after the shortage tapered off, and Amtrak scrambled to find enough rolling stock for the anticipated summer crunch. A mode of travel that seemed marked for extinction in 1970 found itself the beneficiary, by 1974, of new attitudes arising out of the energy crisis. Riding the trains showed signs of becoming a special sort of locomotive chic: relax, save fuel, enjoy your trip. Who needs to be in such a hurry? The vanishing species refused to vanish.

But its survival is far from assured. Its natural predators, the freight-loving railroads, are as intransigent as ever: snapping at a wing here, a leg there, waiting for the right moment to lunge for the jugular. And Amtrak’s own instinct for self-preservation is not as sure as it should be. The corporation is currently entangled in political maneuvering between Congress and the Nixon Administration, a struggle that pits those who favor a modernized nationwide rail network against those who want to quarantine all rail passenger service inside the boundaries of the Northeast Corridor running from Boston to Washington, D.C. The Amtrak executive management, which must satisfy both Congress and the Administration, displays remarkable indecisiveness on the question of whether its own nationwide system is worth preserving. Recently both of these problems—the railroads’ animosity and Amtrak’s own wavering commitment to passenger service outside the Northeast—have been vividly exhibited in controversies about the lines that pass through Texas, particularly the route between Houston and Dallas/Fort Worth and the Inter-American train that runs from Laredo through the Metroplex to Texarkana and Saint Louis.

The Texas experience is an instructive example of Amtrak’s potential; its confusion of purpose; its vulnerabilities; and its uncertain future. For good measure there is also an old fashioned black-caped, mustache-twirling villain: the Southern Pacific Railroad, owner of 3095 miles of vital mainline track in Texas.

Melodrama, then: a tinkling piano in the background while on the flickering screen unfamiliar characters perform another scene from Politics and the Public Good.

Amtrak is governed by an eleven-member board (now being expanded to thirteen), all but four of whom are nominated by the President and approved by the Senate. Except for the secretary of transportation, who serves ex officio, the others are chosen by the corporation’s stockholders, who happen to be four railroad companies—the Penn Central, Burlington Northern, Milwaukee, and Grand Trunk Western. It is thus a hybrid: partly public, partly private. These particular railroads became Amtrak’s sole stockholders because the law creating it provided that any passenger railroad could turn its passenger service over to Amtrak by paying the corporation a sum equal to the railroad’s 1969 passenger losses; the railroad could then treat this expenditure as a tax write-off or receive Amtrak stock for it. Only four railroads found it worthwhile to take the stock instead of the tax loss. As a result, they are entitled to sit down among themselves and select three members of the board.

The money paid to Amtrak by the thirteen railroads that chose to avail themselves of the golden opportunity to unload their passenger service amounted to $197 million. Amtrak, of course, had no equipment of its own, so it used $87 million to buy 1490 cars and 274 locomotives from the railroads. It was then in business—except that this rolling stock showed all the wear and tear that might be expected from decades of deterioration and neglect. Much of what Amtrak got was so decrepit it should have been retired years earlier. “It’s sort of like trying to start an airline with DC-3s,” said an Amtrak spokesman in Houston. Inevitably, passengers have endured an unreasonably high frequency of breakdowns. During 1973, equipment malfunction accounted for eight percent of Amtrak’s delays—12,248 separate occurrences.

Judging from customer comments, Amtrak’s strengths are found in its friendly personnel and its on-board services. Whatever faults the upper-level management of Amtrak may have do not extend to the lower-echelon personnel, most of whom seem genuinely on the passenger’s side. That will come as a refreshing change to anyone who rode the trains in the Purge Years of the Sixties when service hit rock bottom.

The very fact that trains had become so unfashionable now accentuates the comradely sense of adventure involved in riding them. Too often, however, the adventure slips into a struggle against adversity: poor equipment condition, rough roadbeds, inordinate delays, and malfunctioning air conditioning and heating systems all rate high on the list of riders’ complaints. Because the railroads still own the roadbeds, run the trains, and maintain the cars (by contract with Amtrak), most of these problems are not directly within Amtrak’s power to overcome. But they illustrate the way Amtrak’s ability to do its job is dependent upon the American railroad industry, whose delinquencies Amtrak was christened to circumvent.

Many of the passenger cars have been extensively refurbished with new upholstery in snappy color combinations; this is one area in which Amtrak’s investment is clearly showing results. But next to nothing has been done to correct the cars’ greatest shortcomings, their antiquated electrical systems that are the source of air conditioning and heating problems. Until this year, economic considerations dictated that most of the improvements in rolling stock would be the external, less-expensive kind.

Even cheerful and comfortable surroundings, however, are small consolation to passengers who arrive at their destinations chronically late. In 1972 only 53.3 per cent of all Amtrak long-distance trains arrived on time. Does that sound bad? By 1973 the figure had dropped to 30.4 per cent. (Overall performance, including metroliners, turbo trains, and other “corridor” routes, was a bit better: 75 per cent in 1972, 60.2 per cent last year.) Two of the three Texas trains have been running better than average. The Houston-Chicago run posted a 35.3 per cent on-time record last year, ranging from a high of 61.1 per cent in September to a dismal 4.5 per cent in May. The Inter-American (Fort Worth-Laredo) followed a wandering route but arrived on time 55.9 per cent of its 1973 trips, making it the third most reliable long distance run in the nation.

The other Texas train, the Sunset Limited (New Orleans-Los Angeles via Houston and El Paso) managed to be on time only 28.5 per cent of the time in 1973. During July and August it was late every single trip. But the Sunset’s record seems as punctual as Kant’s walks through Königsberg compared to the 1973 on-time performance of the Chicago-New Orleans run (7.5 per cent), New York-Chicago (6.8 per cent), and New York-Kansas City (2.7 per cent).

Failures of signals maintained by the railroad companies accounted for 12,081 delays last year, almost as many as were caused by equipment failures. Slow orders—reduced speeds imposed on passengers trains by the railroads, usually because of poor track conditions but occasionally as a form of harassment—delayed Amtrak 51,911 times. And on 14,884 occasions, passenger trains were held up because freight trains were in their way.

Clearly something had to be done.

Since November, 1973 railroad companies have been required to give passenger trains priority over freights. The law, regrettably, is frequently ignored; Amtrak personnel riding the Inter-American between Dallas and Little Rock have fumed as the train was repeatedly diverted to sidings while freights moseyed past. When not ignored, it can be circumvented: the Inter-American, which uses Missouri Pacific tracks through San Antonio, has on occasion been held up for nearly 30 minutes waiting for Southern Pacific to grant permission for it to cross the SP tracks which it meets at right angles.

In the boldest consumer-oriented action yet, the ICC implemented last April a set of regulations entitled “Adequacy of Intercity Rail Passenger Service.” It ordered Amtrak to provide free meals and hotel rooms to travelers who miss connections as a result of late trains, to supply onward transportation for stranded travelers, and to improve the quality of its equipment.

To the extent these orders are observed, they are a step forward for rail passengers. But they deal with inconveniences that arise on routes already in existence. In Texas there is another whole dimension to Amtrak’s role: what routes shall there be? Between what cities and towns, over what tracks and with what frequency, shall Amtrak provide rail service? This particular issue has not only intensified old rivalries (Fort Worth versus Dallas) and created some lively new ones (Longview versus Greenville); it has also delineated in stark relief the unrelenting contest between Amtrak and its member railroads.

Suppose you are a Houston businessman whose work takes you to Dallas two or three times a month. You don’t particularly like to fly, and by the time you drive to Intercontinental or Hobby, park, wait for your flight to be called, make the airborne trip, perhaps wait for your baggage, and take a cab from Love or D/FW to downtown Dallas, you have spent at least two and a half hours. Making the trip in a cramped bus at 55 mph would take four and a half hours; it just doesn’t suit your style. If you are over the age of 35 you probably remember taking the train; until 1966, passenger trains ran between the two cities at an average speed of 65 mph and completed their trip in exactly four hours. You like that idea: you could relax a while, get some work done, and move around and stretch your legs during the trip from city center to city center.

The Houston-Dallas corridor is the most heavily traveled air route in Texas. It is reasonable to suppose that high-speed, high-quality rail service between these two points would be well-patronized; they are about the same distance apart as Washington and New York, a corridor that even passenger train critics admit is highly suitable for such service.

Houston does have a northbound train: the Lone Star, which follows the route of the old Santa Fe Texas Chief in a wide crescent to Temple, Fort Worth, Oklahoma City, and Chicago. But the route misses Dallas. This has been a source of great consternation to Dallas civic leaders, who chafed mightily upon realizing that their city was the largest community in the nation without Amtrak passenger service. It also made no economic sense: why skip the most important route for businessmen and other travelers?

Why indeed? The reason lies in the fact that Amtrak cannot simply pick a suitable railroad track and run a passenger train over it. Every detail of its routing requires painstaking negotiation with owners of the track. The Santa Fe is one of a handful of railroad companies that preserved courteous, reasonably efficient passenger service even into the Sixties and Seventies; its Chicago-to-Los Angeles Super Chief was the most luxurious train in the country, and the Texas Chief was the best train in this region. The Lone Star follows their tracks from Rosenberg, near Houston, through Temple and Fort Worth because the Santa Fe management remains cordially-disposed toward passenger service. The route bypassing Dallas is, quite literally, the path of least resistance.

Amtrak had always intended to switch the train to Southern Pacific tracks between Houston and Dallas via Bryan-College Station as soon as the necessary arrangements could be made. It would then proceed from Dallas to Fort Worth and resume its existing northbound route, thus providing service between the two largest Texas cities without omitting Fort Worth. In early 1973 Amtrak announced with great fanfare that the switch would begin the following June 10. Dallas spent $6 million to buy and refurbish Union Station in anticipation of the great event. But neither Amtrak nor Dallas counted on the attitude of Southern Pacific’s management. SP declared that passenger trains could not use the route without spending “at least $7.7 million” as the “first phase” of raising the line to “minimum standards” for passenger service. Amtrak wadded up its Dallas-Houston timetables, tossed them in the wastebasket, and sent the train through Temple.

Meanwhile SP called in its lawyers. Using a standard procedure for resolving disagreements between Amtrak and its member railroads, SP submitted the issue to the National Arbitration Panel. It argued that allowing Amtrak to run the train over its tracks would be unsafe and would interfere unreasonably with its freight operations. For nearly eleven months Dallas-Houston service was in limbo while Amtrak and SP pleaded their cases before the Panel.

Anyone familiar with the heavy travel between those two cities would automatically expect them to be connected by a direct, top-quality rail line. But the differences between rail and highway traffic patterns are constantly surprising. The railroads prospered in another era, and to the modern, highway-oriented eye their tracks often careen off in odd directions. None of the Dallas-Houston rail routes is comparable in directness and excellence to Interstate 45. The best—Southern Pacific’s 264-mile track—divides into three distinct portions of variable quality: a high-speed segment between Corsicana and Hearne which forms part of SP’s main transcontinental line entering the state at El Paso and exiting at Texarkana, and two low-grade connecting lines—one from Corsicana to Dallas and another from Hearne toward Houston.

Before the Arbitration Panel, SP raised its estimate, saying that $14.5 million would be required to get this route ready for two passenger trains a day—$8.9 million for the two connecting tracks at either end, and $5.6 million to “ameliorate” Amtrak’s interference with SP’s freight operations on the transcontinental track. Amtrak countered with an estimate of $5.4 million for repairs on the connecting tracks, denying that any of the seven improvements SP wanted on its transcontinental track were necessary. For this amount of money, Amtrak said, passenger trains could make the run in seven hours and ten minutes.

In comparison, Boeing 727 jets were selling for $8.4 million apiece last year.

The Arbitrators commissioned the Philadelphia firm of Louis T. Klauder and Associates to sort out the conflicting claims. In March, Klauder issued its report. Essentially, the firm agreed with Amtrak on the amount of track improvement needed, setting the cost figure at approximately $6 million. But it said Amtrak’s proposed timetable was too slow and recommended instead a schedule of five hours and 45 minutes. This required about $3 million more for new sidings and extensions at Million, Hempstead, Ennis, and Hearne. Klauder agreed with SP that centralized traffic control (CTC) was needed on the transcontinental portion of the track; for that they set a price tag of $2 million, rejecting SP’s claim that the CTC system should be computerized at much greater expense. Total: $11 million. Because the terms of the arbitration agreement provided that Amtrak and the railroad would split the costs equally, that worked out to $5.5 million apiece to provide a tolerably-efficient rail link between Dallas and Houston within eighteen months.

Klauder criticized Southern Pacific for insisting that Amtrak’s trains be limited to speeds no higher than 70 mph on the better segments of the route. If Amtrak were allowed to operate normally at the 79 mph speed limit set by the ICC, Klauder said, the running time could be shortened to five hours and 25 minutes, possibly even four hours and 55 minutes.

(There is an ironic footnote to this particular speed limit controversy. A special private train carrying SP President Biaggini and other company executives on an inspection tour passed through the Dallas area in mid-December last year. Amtrak enthusiasts who managed to get a copy of its confidential timetable gleefully revealed that Biaggini’s train was scheduled to travel at a speed quite similar to the one Amtrak needed—but SP had denied—over these tracks. When SP discovered the leak, they slowed Biaggini to 40 mph on either side of Dallas, less than their own freights had been traveling. Requests from public officials and the news media to get aboard the train and check the smoothness of its ride were refused by SP.)

The response to the Klauder Report surprised everyone but the most cynical Amtrak-watchers. After two years of planning and promises, after a year of arbitration, Amtrak abruptly announced in late March that it was “withdrawing” from binding arbitration and would indefinitely postpone its plans to connect Houston and Dallas. Civic leaders in Dallas were outraged. Republican U.S. Representative Alan Steelman, who had worked harder than any other Congressman to bring about the service, felt especially betrayed. He declared that “action must be taken to open up the Amtrak operation to public scrutiny,” and took the first step himself by sending a detailed request for information to its president, Roger Lewis.

Later, Steelman told Texas Monthly that Lewis had simply said, “I can think of a lot better places to spend five million dollars.”

At press time there was no indication whatever that Amtrak intended to resurrect the Dallas-Houston plan. The Houston businessman who wishes to make the trip by rail must still spend six hours and five minutes riding to Fort Worth, from whence he must catch a bus to Dallas; of course he will not consider it. And the Lone Star still pulls out of Houston’s SP Station, bound for Chicago, on tracks that carry it 35 miles southwest in the direction of Corpus Christi before turning northwest toward Fort Worth. The puzzling thing is Amtrak’s apparent willingness to let this situation continue. Southern Pacific quite readily casts itself in the role of villain, performing its part with aplomb and chuckling, perhaps, as the audience hisses; SP at least knows what it believes and acts accordingly. But Amtrak! If this is really the Perils of Pauline, why has Pauline absconded with the villain? For sheer implausibility, it smacks of Patty and the SLA.

Southern Pacific has been far more cooperative on the other Texas passenger route that uses its tracks: the Sunset Limited serving Beaumont, Houston, San Antonio, and El Paso. This line is the main transcontinental link from Washington, D. C., through New Orleans to Los Angeles, and it was included in the Amtrak system from the beginning, contractually forcing SP to maintain the tracks at 1971 levels. As one rail buff remarked, “Southern Pacific makes a lot of noise, but if they finally have to do something, they usually do a good job of it.” The non-stop 211-mile trip from San Antonio to Houston takes four hours and fifteen minutes; unfortunately, the westbound run is scheduled in the middle of the night in order for the train to depart New Orleans and arrive in Los Angeles at convenient hours.

From Flatonia to El Paso, the Sunset follows the western portion of the same transcontinental SP track that runs from Corsicana to Hearne. Amtrak officials consider it one of their best passenger routes, with a smooth roadbed and relatively high-speed service. Few trains have shown such a marked improvement in the past ten years. The Sunset was once the nation’s most notorious example of railroad company harassment. Anxious to get rid of this particular responsibility, SP made it impossible for customers to obtain accurate schedules or reservations. Houstonians arrived to board the train and found no agent to sell them a ticket in the unmanned station. Delays were legion. Pullman cars were removed in the early Sixties, forcing everyone to sit in coaches for the 2000-mile, 45-hour trip between New Orleans and Los Angeles. Towards the end, passengers were treated like prisoners of war. The dining car was replaced by a vending machine that often didn’t work. Since the Sunset never stopped at any station long enough for passengers to get off and find something to eat, many passengers who lacked the foresight to bring along two days’ worth of box lunches arrived at their destinations dazed, famished, and determined never to ride another train. It is appropriate to remember that Amtrak, whatever its faults, has put a stop to things like this.

The Sunset is once again a popular train, even though it runs only three times a week in each direction and remains at the mercy of SP delays. Riders have returned to it in droves, undeterred by a recent twenty per cent increase in fares. By the tenth of June, coach seats were fully booked for six weeks in advance. The sleepers are even tighter. One San Antonio customer who tried early in June to reserve a roomette to Los Angeles for November 21 discovered the “No Vacancy” sign was already out.

The third Amtrak train in Texas is spectacular testimony to three things: Southern Pacific’s clout, Missouri Pacific’s ingenuity, and Amtrak’s determination not to spend a dime more than it has to outside the Northeast Corridor. If the Dallas-Houston route is a melodrama, the Inter-American is a comedy of errors.

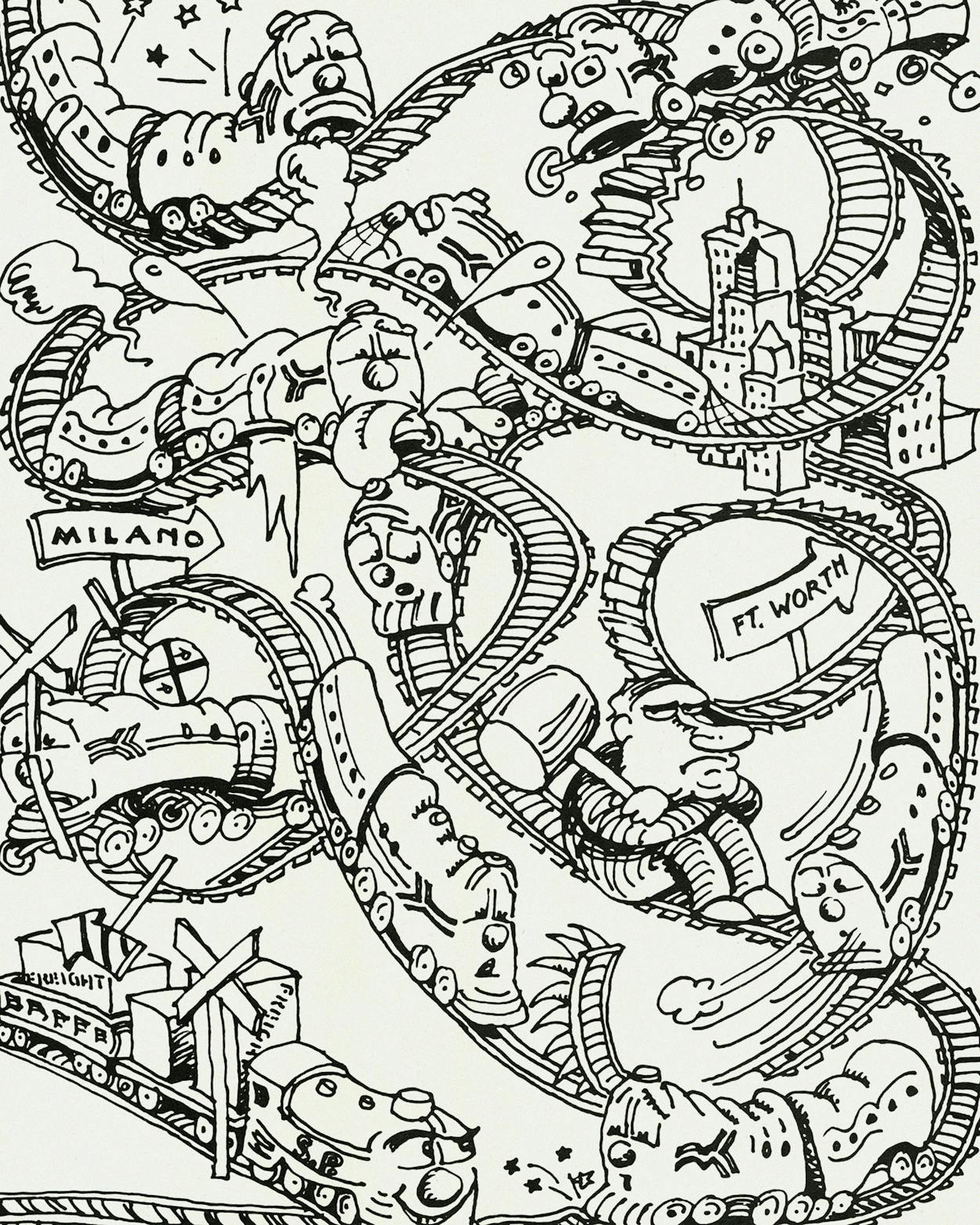

Designed to connect the United States with Mexico on a route from Saint Louis through Texarkana to Laredo, the Inter-American manages to wander all across the eastern half of Texas on the way to its destination, avoiding hostile railroad tracks and sniffing out the cheapest path like a heat-detecting missile. How to begin the story of this lovable, pitiful train?

Until September 27, 1970, the Missouri Pacific (MoPac) Texas Eagle provided service from Saint Louis to Laredo via a reasonably direct route through Texarkana, Palestine, Austin, and San Antonio. On that date, service on the Texas portion was terminated by permission of the Texas Railroad Commission, which professed to believe MoPac’s argument that the train was actually an intrastate Texas train from Laredo to Texarkana. It just happens, said MoPac, that another train runs from Texarkana, Arkansas, to the Missouri border, and even though it’s blue and white and looks just like ours, it’s really only an Arkansas intrastate train. Ditto for that other one that runs from the Missouri border to Saint Louis; that’s just an intrastate Missouri train. Funny, that. By carving up the Saint Louis-to-Laredo run into three imaginary intrastate trains, the Texas Railroad Commission was able to circumvent ICC jurisdiction over interstate trains, and they snipped off the Texas Eagle in the middle of the night despite the formal protests of lawyers as persuasive as Charles Alan Wright. Surprisingly, the ICC let them get away with it.

U.S. Representative J. J. “Jake” Pickle, an Austin Democrat, then began a prolonged fight to get some sort of service restored. Amtrak installed a small shuttle train between Fort Worth and Laredo in early 1973, intending to re-establish the full Saint Louis route as soon as President Nixon’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) released the necessary impounded funds. On March 13 and 14, 1974, the inaugural run of the complete Inter-American took place along what must be the most peculiar route in the entire Amtrak system.

Assuming a goal of connecting as many major population centers as possible without sacrificing expeditious service, the train’s logical path is to follow Cotton Belt tracks from Texarkana through Mount Pleasant, Commerce, and Greenville; switching there to Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy) Railroad tracks through Dallas, Hillsboro, Waco, and Temple; and moving on to Missouri Pacific tracks at Taylor for the balance of the trip through Austin and San Antonio to Laredo.

Because Katy is not a member of Amtrak, a rental fee would have to be paid for the use of its track. About $5 million in repairs were also needed—a figure that no one disputes. These, however, were easily surmountable problems. The impoverished Katy, scarcely able to improve its own tracks, stood to benefit considerably if someone else footed the bill. Prodded by economics, its already pro-passenger management offered to let Amtrak pay off the repair costs by deducting them in installments from the track rentals. Katy would get better tracks and for ten years Amtrak would have had the use of them without actually paying Katy any cash at all. Considering the attitude of most railroads the Katy offer was quite generous.

But the Inter-American could not reach Katy’s Greenville-to-Dallas track without using Cotton Belt first. And Cotton Belt is owned by Southern Pacific. When Amtrak tried to begin negotiations for use of those tracks two years ago, Cotton Belt telegraphed back a flat NO. Unwilling to get into a prolonged arbitration battle like the Dallas-Houston route dispute, Amtrak took no for an answer. While Greenville civic leaders despaired and the 2600 Dallas-area students at East Texas State University in Commerce felt stranded, the Longview Morning Journal published an Extra celebrating the arrival of the Inter-American on Texas & Pacific tracks, the 31-mile-longer route chosen by Amtrak to avoid a confrontation with Southern Pacific.

In the Metroplex an even bigger brouhaha developed. Re-routing the train from Cotton Belt tracks to T & P tracks meant that it would now enter the Dallas station heading north instead of south. If it departed Dallas toward Hillsboro on Katy tracks, as Dallas leaders preferred, it would have to back out of the station for nearly two miles onto a Santa Fe spur before pulling forward onto Katy tracks.

The Dallas Amtrak Committee thought this was worthwhile, but their counterparts in Fort Worth were furious. The Tarrant Countians wanted the train to come to their city next, before it headed south. The Dallas-Fort Worth rivalry arose anew. For Dallasites the question was one of cool logic. Routing the train through Fort Worth would consume so much time that the southern portion of the schedule would become disastrously slow. Why, they asked, should all the people from San Antonio and Austin who are headed for Dallas have to go all the way over to Fort Worth first? “It’s not right,” said one Dallas observer, “to sacrifice the vitality of the whole thing to satisfy a few people in Fort Worth.”

Fort Worth didn’t see things that way. Statistics were presented showing that some people really did want to go to Fort Worth, especially those who lived there already, but nobody really thought the battle would be won with statistics. Deep down, nobody in Fort Worth cared about the statistics. What galled them was Dallas’ nerve. “My God,” they thought to themselves, “we’re the rail center in this state. We’ve put up with a lot. And now they’re trying to take our trains away from us too.”

As it turned out, Fort Worth needn’t have worried. Amtrak was unwilling to pay anything to repair the Katy tracks south of Dallas, even on the exceptionally attractive terms Katy’s management had offered. Money was the uppermost consideration in the minds of Amtrak’s Eastern-oriented decision-makers, and a dog-leg through Fort Worth was cheaper because the train could join up there with the southbound Santa Fe tracks already in use for passenger service between Fort Worth and Houston. Cheaper—but far less convenient for most of the customers who might have used it. To save money the Inter-American heads west from Dallas instead of south. An hour and five minutes later it creeps into Fort Worth’s passenger station.

At Fort Worth a strange ceremony is performed. Amtrak employees march through the coach cars rousting passengers into the aisles while they reverse the backs of every seat. Meanwhile, the locomotive is disconnected, moved around the yard with the aid of a switch engine, finally to be reconnected at the opposite end of the train. The configuration of the tracks at Fort Worth forces the Inter-American to curve 90 degrees northward onto Santa Fe tracks as it approaches the passenger station. Since it will depart southward on those same tracks, everything must be reversed at considerable expense (union rules forbid the locomotive to make the switch under its own power) and delay (in addition to the time required to reach Fort Worth, the schedule calls for a 30-minute stop there; it is usually closer to an hour). Sleeping car passengers have an even more unsettling experience ahead of them. Because their seats are not reversible, they must spend the rest of their trip riding backwards.

All of this is necessary because a short interchange track is missing in the southeast quadrant of the cross where the tracks meet in the Fort Worth yard. If the train coming in from the east could curve south onto the Santa Fe tracks and then reverse into the station a few hundred yards behind it to the north, all the confusion and delay could be avoided. In fact, the interchange is not actually missing; it is simply so run-down that passenger trains cannot safely travel across it. Switch engines use it every day. Missouri Pacific (whose subsidiary, Texas & Pacific, owns that particular piece of track) has put a price tag of $300,000 on the thousand feet of retying and the two electric switches required to get the interchange in shape. Knowledgeable railroading experts call MoPac’s demand exorbitant. They say it could be fixed for half of that. Whether they are right or not, even such a minimal investment as this is more than Amtrak seems willing to spend for track improvement on the orphan Inter-American. So the ceremony goes on.

About this time a few savvy passengers remember that they had arrived in Dallas at 7:30 a.m. Their watches now show something like 9:15 or 9:30, and they are not a bit closer to their south Texas destinations.

From Fort Worth to Temple the Inter-American rocks along at a brisk 79 mph over the high-grade tracks of the friendly Santa Fe railroad. For through passengers this segment poses no problems. But for anyone headed for Waco, the Santa Fe route is a slow burn. One of the lamentable misfortunes of Texas railroading is the happenstance that so many of Santa Fe’s tracks slice through depopulated boondocks, missing important population centers. Waco passengers must commute eighteen miles to the little town of McGregor (pop. 4365) to catch the train. Amtrak’s refusal to improve the Katy tracks south of Dallas not only produces the drawn-out Fort Worth fiasco; it effectively squanders the Inter-American’s potential usefulness to Waco-Dallas travelers. U.S. Congressman Bob Poage, a Waco Democrat, had a conniption when he saw that route; but in spite of his 37 years of seniority he has been unable to change it.

Temple is the place where things finally go completely haywire. By car, Temple is 68 miles from Austin; the trip ordinarily takes about an hour and 15 minutes. By train, using Amtrak’s infamous “Milano Connection,” Temple is 113 miles from Austin and the trip takes 2 hours and 32 minutes, if you are lucky.

Here is the problem: from Temple the direct route would follow the Katy tracks to Taylor where it would meet the Missouri Pacific tracks for the remainder of the trip to Laredo. But these are the same south-of-Dallas Katy tracks Amtrak has expended so much effort to avoid. Amtrak is unwilling to share the repair bill even for this short section. Moreover, there is another problem of the type that makes anyone conditioned to automobile driving shake his head in bewildered disbelief. Even though the Santa Fe tracks cross the Katy tracks in Temple, there is no way for a train to switch from the former to the latter. If two highways cross on a map, we naturally expect to be able to get from one to the other. But railroads inhabit a different world. Here is a 200-mile trip from Fort Worth to Austin, and the essential link depends on a few feet of connecting track that doesn’t exist. It could be built, even though a highway and a nearby house make construction a little trickier than the link at the Fort Worth station. But it hasn’t been. The realization dawns: this country is crisscrossed by railroad tracks and yet you still can’t get there from here.

Well, eventually you can, of course. Austin lies southwest of Temple, but the baffled, homeless Inter-American proceeds southeast toward Galveston for 44 miles until it finally hits the MoPac tracks about an hour later at Milano (pop. 380). At this point it is exactly four miles closer to Austin than it had been in Temple. Reaching Milano it creeps and jerks indecisively through high grass and empty fields. Said one passenger: “If you didn’t know the damn thing was on tracks, you’d think it had gotten lost.”

Once onto Missouri Pacific tracks, the Inter-American’s wanderings are over. But any ideas Amtrak might have about clipping on down to Laredo without delay have been thoroughly dashed by MoPac’s management, which has imposed a 50 mph speed limit on the train between Milano and San Antonio. MoPac’s 1962 timetable shows a passenger train speed limit of 79 mph for this section of track, along with a 50 mph speed limit for freights. Now MoPac insists that the Inter-American dawdle with its freights.

With so many obstacles the result is predictable. The trip between Dallas and the Alamo city consumes a preposterous amount of time, even for travelers who aren’t in a hurry. If you leave Dallas on Amtrak’s current route you should get to San Antonio eight and one-half hours later. Put a pencil to it. Braniff can fly you to Bogota quicker than that.

The complications are not limited to the train itself. MoPac owns the Austin station, an unprepossessing survivor of the Eagle’s days, some distance from downtown. Amtrak passengers are only allowed to use the former “colored” waiting room. In the large uncrowded parking lot nearby, MoPac suddenly erected “No Overnight Parking” signs last year, depriving passengers who took the thrice-weekly train of any place to leave their cars for what was of necessity an overnight trip. One passenger who ignored them returned to find that MoPac had towed his car away. Only after he sued for damages—and won—did the company take the signs down.

At San Antonio, Amtrak’s obsessive thrift and the problem of dealing with separate railroads again become apparent. For lack of a 1500-foot connecting track and some minor repairs estimated at $30,000, the Inter-American cannot reach the SP station. Consequently it stops in the middle of a city street more than a mile away, and passengers are ferried to and fro by bus. When the train is crowded the number of disembarking passengers and their baggage sometimes exceed the capacity of the bus, which must then make a second trip while the unlucky stragglers wait. In the meantime it has been known to rain.

Passengers who are game for the rest of the trip soon discover that it gets even slower. Between San Antonio and Laredo, MoPac’s speed limit is a somnolent 40 mph, one-third slower than twelve years ago. Several times this summer, the Inter-American has been held below 30 mph south of Cotulla. At that speed the generators do not produce enough electricity to keep the air conditioning running. By the time it reaches Laredo the reserve batteries are dead, leaving the train without air conditioning until it returns to San Antonio for recharging the next day. These low “speed limits,” moreover, are just an unofficial edict of Missouri Pacific, aimed solely at Amtrak. Where the Federal Railway Administration sets the official passenger train limit at 59 mph, MoPac forbids its engineers to operate the Inter-American faster than 40. What can Amtrak do? “Well,” says a MoPac spokesman, “if Amtrak wants higher speeds, they are free to negotiate for higher speeds.” With whom? “With us.”

If the Inter-American runs this demoralizing gantlet and arrives on time, it will reach Laredo at 8:05 p.m. Here the final irony awaits passengers who intend to continue on to Mexico City aboard the Aztec Eagle: the Eagle left 40 minutes earlier. They must check into a hotel and wait nearly 24 hours for the next day’s train.

In all the confusion this lesson should not be lost: the Inter-American is packed with passengers. It has been running at or near capacity all spring and summer, sometimes standing-room-only. Could there be better evidence that rail travel has potential in Texas? Rail buffs and nostalgia freaks cannot fill the same train day after day. Because of its absurd route, its thrice-weekly schedule, and its snail-like pace, the Inter-American’s appeal cannot be found in practicality or efficiency. Viewed strictly as a mode of transportation from point to point it cannot compete with planes and buses. Yet riders crowd aboard enthusiastically, willing to give up speed in exchange for something else. If the Inter-American proves anything, it proves by its very faults that people must ride trains because they like them. That little psychological truth can be Amtrak’s biggest asset, if Amtrak doesn’t waste it.

Rail passenger service in Texas is an interesting case study for Amtrak-watchers. The Inter-American and the Lone Star clearly show that railroad company harassment is not the only force thwarting the establishment of rational routes and schedules, although several have obviously done their best to interfere. Underneath the fight between Amtrak and its member railroads is the fight between Amtrak and itself.

Every new passenger aboard an Amtrak train is a source of disappointment to those who confidently expected the corporation to fail. Now that rail travel is once again on the upswing, the likelihood that Amtrak will collapse from passenger disinterest seems more remote than ever. But as a creature of politics, Amtrak is vulnerable to political pressures. Its very success has heightened the internal machinations against it, for the newfound passenger support means that Amtrak can be laid to rest only by inducing it to undermine its own system.

The pressures against Amtrak are visible in several areas: in the lobbying efforts carried on by rival forms of public transportation like the bus companies and the airlines; in the influence on Amtrak’s board by railroads acting on the dictum, pace Clausewitz, that bureaucratic diplomacy is simply the continuation of their old passenger wars by other means; and in the doctrinaire pronouncements of politicians who condemn Amtrak’s operating subsidy without acknowledging that airlines and buses are subsidized too.

The Nixon Administration’s ambivalent attitude toward Amtrak resembles that of a proud father who shows off his healthy baby to an admiring crowd, and then, when the admirers’ backs are turned, tries to smother the helpless infant with a blanket. While a sprightly advertising campaign announces that “Tracks are Back,” Secretary of Transportation Claude Brinegar declares that rail passenger service should be scaled down. Addressing the National Press Club in May, the Secretary—whose support is important to the corporation’s success—suggested that service outside the Northeast Corridor should be discontinued. “I seriously question Amtrak’s role in trying to provide cross-country service in competition with our fine air and intercity bus service,” he said.

Unlike his predecessor John Volpe, who started as a highway man but soon developed sympathy for expanded rail service, former California oil executive Brinegar shows no signs of wanting to improve Amtrak’s performance in places like Texas. When the Administration’s list of nominees for the new Amtrak governing board was being prepared this spring, he bitterly opposed the re-appointment of Charles Luna of Dallas—the retired labor union leader who has been the passengers’ only outspoken advocate on the current board. Brinegar called him a disruptive force.

“I don’t know how he could be the judge of that,” said Luna, “because he hasn’t been to but one meeting since I’ve been there and then didn’t stay but about an hour. I think he got a little teed off with me. . . . I haven’t been too—as the little boy said—too respective of his high office. I’ve dealt with ’em before.”

Ultimately Luna was kept on the list by a direct appeal to the White House by Congressman Alan Steelman. (Senator Warren Magnuson, who said his Commerce Committee would not consider any of the nominees unless Luna was among them, helped Steelman in no small measure.)

With three railroad company executives entitled to serve on the current eleven-man Amtrak board by virtue of their companies’ stock holdings, with Brinegar serving ex officio, with another member simultaneously acting as chief executive officer of a major bus company, and with the eleventh seat (designated by Congress for a “consumer representative”) left vacant for three years through presidential inaction, it is not hard to see how the opponents of nationwide rail passenger service have enjoyed a heady advantage on such questions as whether Amtrak shall spend money to improve track between Houston and Hearne.

The capital borrowing authority in Amtrak’s 1974 budget includes a line item of $50 million exclusively for track improvement. None of it has been spent. Brinegar wants to release only $20 million and limit that to repairing tracks in the Northeast Corridor. For lack of a thousand-foot strip of track, you may recall, passengers on the Inter-American must undergo the prolonged seat-switching, engine-swapping routine required to reverse directions in Fort Worth.

An announcement on June 4 that the Department of Transportation would guarantee $347 million in loans to Amtrak for the purchase of new rolling stock has not entirely dispelled the suspicion that the Administration wants to discontinue long-distance service when (and if) the political coast is clear. Nearly everything in Amtrak’s order is readily adaptable to freight operation or East Coast requirements. The 200 new Budd Company coach cars will be “highly flexible,” according to an Amtrak spokesman, and will include “track seats adjustable for either long-haul or short-haul needs.” The 135 new locomotives intended for western and midwestern trains will improve Amtrak’s critical power shortage, but they can be converted to freight service any time in the future by a simple change of gear ratios. Six French turbo-trains and 57 metroliners were ordered, but nothing was said about new dining cars or sleepers, both of which are currently in short supply. The decision to forego the diners lent further credence to persistent rumors that Amtrak intends to move toward pre-cooked airline-type food and dispense with diners altogether, as has already happened on some Eastern Corridor trains.

The airlines’ standardized efficiency is familiar to Amtrak’s Vice-President for Marketing, Harold Graham, who previously was an executive with Pan American World Airways. “What we want to do,” he told Fortune magazine this spring, “is put our major emphasis on coach class. We want to get as many people as we can on the train.” Veteran train passengers know that the un-standardized amenities are the soul of rail travel, and they are beginning to look askance at indications that Amtrak would like to discard them in favor of some sterile, one-class concept of service. Railroad trains are the last place one expects to find leveling Jacobins.

Fortune, which makes a specialty of peering inside American executives to find out what makes them tick, gave the Amtrak leadership embarrassingly low marks [“Amtrak is About to Miss the Train,” May, 1974]. “Seldom has a company been blessed with such an unexpected opportunity and seemed so determined to blow it,” mused Fortune. “Amtrak’s troubles are primarily a failure of management.” Most of the blame was placed on President Roger Lewis, a frequent target of passenger groups, who, the magazine hinted politely, was out of his depth. Lewis, like Graham and many other senior managers at Amtrak, came from the airlines and has an impatient contempt for the railroads’ traditional way of doing things. “There seems no way to escape it,” Fortune concluded. “Amtrak will go on wobbling down the track until its present managers, starting with Roger Lewis himself, are replaced by executives with the stuff to run a better railroad.”

In various unexpected ways, the current Amtrak leadership has hindered the plain best interests of rail passengers. In one case brought by the National Association of Railroad Passengers (NARP) to enjoin the discontinuance of a train in Georgia, Amtrak appealed all the way to the United States Supreme Court to win a ruling that private citizens lack standing to sue Amtrak. The effect of this January 9, 1974, decision has been to establish that passengers have no legally-enforcable rights to good service. Only the United States Attorney General has standing to enforce Amtrak’s statutory responsibilities.

Characteristically, Amtrak has not asked him to take action against the railroads that repeatedly have given priority to their freights, contrary to law—an offense that occurred more than 2300 times during the last two months of 1973. Instead of trying to enforce the law, Amtrak is proposing to pay a bonus to railroads when they bring the trains in on time. Nor has any effort been made to seek review of the disconcertingly low speed limits required of Amtrak trains by Missouri Pacific and Southern Pacific.

For rail passengers who dream idealistically of the service that Amtrak has the potential to provide, perhaps the greatest shock was the corporation’s opposition to the ICC’s “Adequacy” regulations. Amtrak formally opposed such wholesome things as (1) a nationwide toll-free reservations system; (2) stricter on-time requirements; (3) meals and shelter for travelers stranded by cancelled trains; (4) checked-baggage facilities; (5) air-conditioning capable of cooling the cars below 80° on a 100° day; and (6) private restrooms on sleeper cars. Amtrak even argued that a proposed regulation requiring it to keep sleeping cars “sanitary, free of debris and objectionable odors, and water tight” was unreasonable. The ICC imposed each of these regulations anyway. Amtrak has retaliated by asking Congress to remove most of the ICC’s authority over passenger train standards.

At press time the list of presidential nominees to the new thirteen-man board was being considered by Senator Magnuson’s committee. Owing to intense pressure from passenger-oriented congressmen, the new nominees are not as one-sided a group as the current board. But considerable effort was exerted simply to keep them from being as overwhelmingly pro-passenger as Congress would have liked. Knowing that the future of passenger service in the Southwest may well depend on the complexion of the new board, which is likely to be confirmed intact, Amtrak watchers in Texas size up the candidates this way:

Five nominees are considered unsympathetic to passenger needs and nationwide service: the three railroad executives; Brinegar; and Amtrak’s President Roger Lewis (as preposterous as that may sound).

Five others are considered sympathetic: Luna; retired General Frank Besson; and three “consumer representatives.”

The rest may hold the balance of power. They are Gerald Morgan, a former vice-president of Amtrak who was at odds with Lewis; Robert Galbraith Dunlop, a Sun Oil Company executive; and Donald Jacobs, a professor of finance at Northwestern University. Morgan is expected to side with passengers, but Dunlop and Jacobs are friends of Brinegar’s and their votes are in doubt. Both told Magnuson’s committee that they supported nationwide rail service. Until they prove it, many observers will remain skeptical—for without these two votes the pro-passenger faction can be out voted, seven-to-six.

Tucked away in the 1970 Rail Passenger Service Act is an obscure provision that allows Texas to take the initiative in developing passenger routes within its borders. Section 403(b) permits “any state, regional, or local agency” to request new passenger service over routes of its own choosing. If the agency agrees to cover at least two-thirds of any losses, Amtrak must operate the train. The idea is that Washington is not the only place to solve transportation problems; the states and localities, which build highways and subsidize airports, have some responsibilities, too. Several states, including Pennsylvania and Illinois, already are supporting Section 403(b) trains.

A struggling Austin-based organization called the Texas Association for Public Transportation has proposed three new rail links: Austin-Houston, El Paso-Dallas, and Fort Worth-Denver. Noting that Amtrak’s recently-purchased French turbotrains are capable of 150 mph speeds, TAPT has also urged an evaluation of their practicality for runs between Fort Worth, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio. At a minimum, the basic Dallas-Houston route for which Amtrak abandoned support last March could be speedily established with state assistance.

Five months ago TAPT submitted to the Texas Mass Transportation Commission a plan for a $20,000 feasibility study of existing and potential routes. Asked what action had been taken, TMTC Executive Director Russell Cummings said, “My Commission has never considered it. Our entire budget is about $22,000 for everything we do other than salaries. We’re obviously not in a position to fund any kind of a $20,000 study. We haven’t got $20,000.”

He is right, of course; the Legislature’s appropriation for the TMTC has been niggardly. But Cummings’ approach to 403(b) service indicated that lack of money was not the only impediment to a thorough study of rail travel potential.

“First of all you’ve got political problems,” he said. “The Texas Railroad Association’s position is that they don’t want to be in the passenger business, and further that they will resist by all legal means at their disposal anybody else using their tracks and right-of-way for passenger purposes. Plus the guarantee of two-thirds of the operating losses: you’re talking about a ton of money.

“That doesn’t seem to be the proper place to sink our teeth . . . There are so many things we ought to do that cost a lot less money that would do some good right now, that it just doesn’t seem to be worthwhile for us to devote a lot of attention to that long-range and very expensive proposal.”

The established transportation interests in Texas are dead set against rail travel [see “The Highway Establishment and How It Grew,” Texas Monthly, April 1974]. Walter Wendlandt, Director of Transportation at the Texas Railroad Commission—note the title well—gave an ungentle reminder of that attitude when he recently told a gathering of intercity bus operators that “Amtrak is a failure. . . . It’s beyond my comprehension to think there will ever be railroad passenger service” comparable in style and speed to buses. Later Texas Monthly asked Wendlandt about Section 403(b) service. “I don’t think it’s feasible,” he said flatly. “There’s a lot of sentimentality and emotion about riding trains because we used to go see grandmother and grandfather on the train. But appeal shouldn’t have anything to do with it. It’s who gets you where you want to go when you want to go there for the least cost. When you look at those factors, it’s clearly bus service.

“I guess I’m a believer in a bus system,” he added. “I believe in what the buses can and are doing for the small towns of Texas.”

The very officials who are in the best position to encourage rail passenger service in Texas seem to be the ones most anxious to recite a litany of its shortcomings. In the meantime the Texas Highway Department is proceeding with plans to build a superhighway from Lubbock to Houston at a cost of nearly a million dollars a mile.

The urban areas of Texas stand to lose the most if Amtrak and the state bureaucracy continue to treat rail travel as a stepchild. The need for better intercity public transportation has become obvious since the energy crisis began. Private automobiles are less practical now that gasoline is over 50 cents a gallon. At 55 mph the auto and the bus are too slow for the great distances between several major Texas cities. In terms of comfort there is no contest between highway transportation and the kind of rail transit offered by the roomy metroliners that now hit speeds of 110 mph between Philadelphia and New York. Like the Northeast, Texas has its population corridors, although fewer people think of them that way. Not much imagination is required to visualize a well-patronized express rail right-of-way from Fort Worth – Dallas to San Antonio, serving half a dozen population centers and using the Interstate-35 median for much of the distance, as TAPT has suggested.

In Texas as in Europe, medium-distance interurban rail service is the most sensible way of accommodating the most travelers most comfortably and most efficiently. To resist it ought logically to be a losing battle. But TAPT, a puny David, has so far had scant luck attracting the attention of bureaucratic Goliaths, much less overcoming them.

Governor Dolph Briscoe has spoken vaguely of wanting to see a coordinated transportation plan for Texas. If his thoughts include Section 403(b) rail passenger service, which will require legislative appropriation, he must be prepared to push for it in the 1975 Legislature. Otherwise Texas’ system of biennial sessions will delay the question to the 1977 Legislature, stalling any effective operating plan until 1978 at the earliest.

Some politicians who have had bad experiences with Amtrak doubt that Section 403(b) is a worthwhile risk for Texas. Says Congressman Alan Steelman: “You’re at Amtrak’s mercy on equipment and schedules; you’re being asked to assume some of the losses without having any control over the service.” He prefers to circumvent Amtrak’s apparent disinterest in its Texas trains by trying to get the routes written directly into law, leaving the Amtrak management no choice but to run them as ordered. An act of Congress spelling out the route and type of service to be provided between Dallas and Houston would, he thinks, be “preferable to a lawsuit” even if the U.S. Attorney General could be persuaded to bring one. And it would place the financial responsibility for operating that train on the same people who already link New York and Boston, Los Angeles and San Diego, Saint Louis and Chicago, Portland and Seattle.

Foiling Amtrak’s management by act of Congress should not be necessary, of course, any more than Texas should have to subsidize rail transportation between the country’s sixth and eighth largest cities. But both may be. To date there has been no incontrovertible evidence that Amtrak intends to get down to the business of running high-quality trains in this part of the country. The Nixon Administration’s pronouncements (and nominees to key positions) reveal a stubborn refusal to believe that popular support for rail travel could actually be returning. Secretary Brinegar’s continued influence keeps Amtrak’s fate in doubt. Congress presently offers the only political counterweight to his “Northeast Corridor” doctrine. Significantly, Congressmen are more responsive than usual to public pressure on an issue like this, with its fashionable “consumer” overtones. But without firm Congressional action this year, Texans who might like to ride a modern-day Flying Express will find themselves coping with the Inter-American—if they even get to keep that.

Passengers who have flocked in such numbers to the surviving trains seem to feel that Amtrak is worth saving. At the moment, though, Congress may have to save it from itself.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Business

- Longreads

- Houston

- Dallas