On a Wednesday afternoon in March, the 22 students in the Baylor University Musical Theatre Workshop trickle into their classroom, chitchatting and pulling last-minute gulps from water bottles. Clad in backwards ballcaps, ripped jeans, and T-shirts, they slide into chairs and adjust the stands that hold their sheet music or tablets. Their instructor, Lauren Weber, passes along a few pieces of feedback from a music director in New York, and the students jot them down before the pianist plays a few introductory notes. The class takes a collective breath and launches into “An American Eclipse.”

“It’s the coming / of our future / and of progress / brave and bold . . .”

Instantly the room is transformed. The song is immense and celebratory; the space feels too small for the coming of this future, for this optimism and anticipation. The sopranos hold “bold” in an extended high G that soars aloft. Students who, moments ago, were hunched over their phones now sit meditation-cushion straight and gesture expressively.

“It’s the rise of / a rich and powerful nation / the divine most have planned / for a land hard-won . . . / . . . an American eclipse / when the moon meets with the sun. All the world will be our judge / and decide how well we’ve done.”

As the last notes fade, the space shifts from a concert hall back into a gray-walled classroom. Weber’s fellow instructor Guilherme Almeida nods. “Very good. Let’s do it again from the top.”

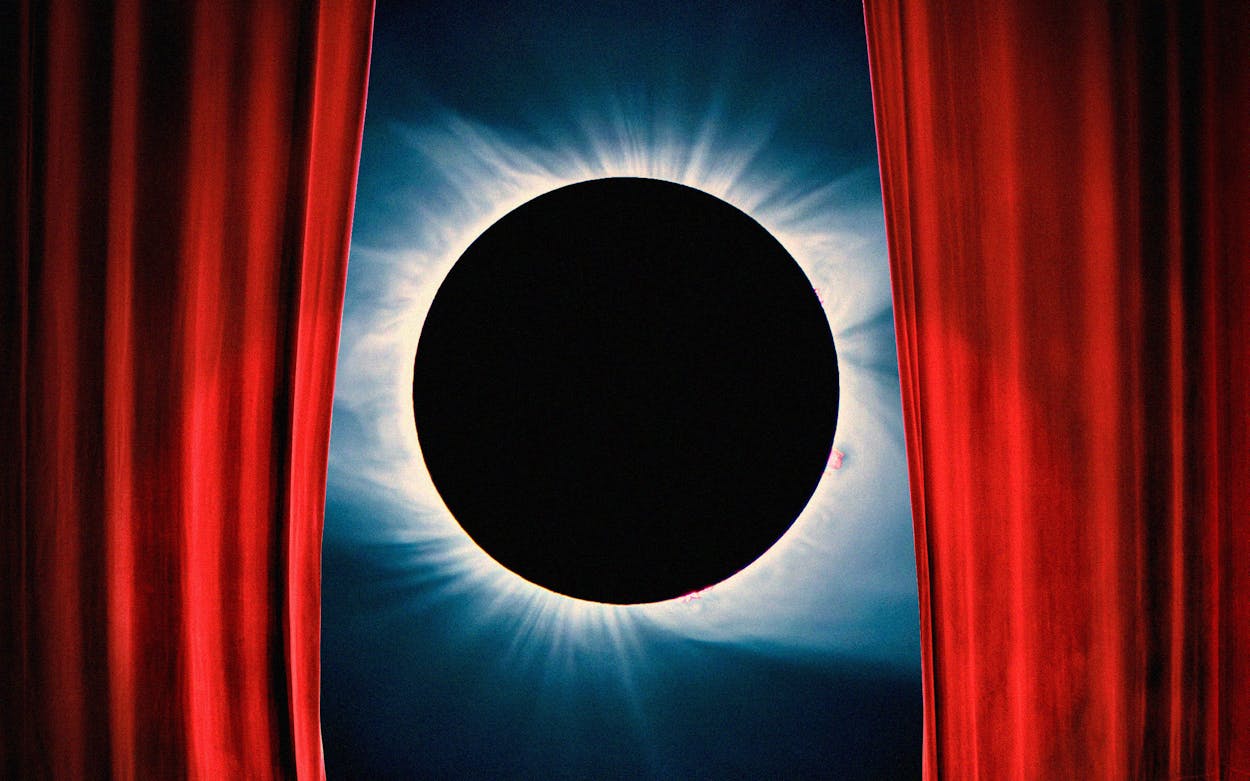

On July 29, 1878, the shadow of a total solar eclipse swept across North America, racing from Alaska across Canada and the American West before reaching the Gulf of Mexico. In Texas, the moon’s umbra touched Pampa, then Wichita Falls, Fort Worth, Waco, and Beaumont. Most of the population did not understand the solar mechanics at work, and some, steeped in the apocalyptic theology of the day, interpreted the late-afternoon darkness as a harbinger of the Second Coming. But elsewhere in the path of totality, scientists seized on the opportunity to study the heavens—and to advance personal agendas.

Nearly 150 years later, students at Baylor University will present that moment in song alongside seasoned Broadway performers. On April 7, the department of Theatre Arts will showcase a concert of songs from American Eclipse, a new musical in development. Based on the 2017 book of the same name by former NPR science correspondent David Baron, the show has been in the works for nearly five years, and Sunday’s performances are the first for a public audience. Six Broadway actors, several of them Tony winners or nominees, play the major roles, while Baylor students make up the chorus and play bit parts. It’s a rare opportunity for undergraduates to work alongside such accomplished professionals.

“As the people in the musical are trying to prove themselves and find this eclipse and discover things about the world, we’re trying to prove ourselves,” says junior theatre performance major Melia Messer.

Baron, who has traveled to witness eight total solar eclipses around the world, wrote his book about the 1878 event because it exemplified how significant eclipses were for scientific research in the nineteenth century. At the time, they offered a rare opportunity to study the sun, so nations invested in numerous expeditions to the path of totality. Baron’s research took him to the Library of Congress and archives at Baylor and in other small Texas towns.

The narrative follows three characters based on real historical figures, each with their own motivation to study the eclipse: the inventor Thomas Edison, who hoped to cement his reputation as a true scientist, not just a tinkerer; Vassar astronomer Maria Mitchell, who organized an all-female expedition to the West to prove that women were capable of conducting scientific research; and expert asteroid hunter James Craig Watson, who was determined to prove that the planet Vulcan existed between Mercury and the sun.

Their expeditions unfolded in a nation only thirteen years removed from a civil war and straining to prove itself to the rest of the world. Industrialization had brought new affluence to the northeast, and the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 had increased access to West—while accelerating the displacement of Indigenous people. Still, Baron argues, the United States had yet to establish itself as an intellectual power.

“This was a chance to show Europe that we actually could compete in the scientific realm,” Baron says. “The eclipse excited the public. It was almost like the moon landing of a century later.”

Two years after the book’s publication, Laura Ivey, a producer of film, theater, and television, picked up a copy. As she read, she imagined an epic stage show about the characters’ journeys west.

“In developing a musical, you think, ‘What sings?’ ” Ivey says. “What’s useful for singing in a musical is internal things”—emotions that people typically keep private. The characters in American Eclipse were full of internal longings and conflicts that are the stuff of great songs.

Ivey and her business partner, Janet Brenner, have together produced Mrs. Doubtfire, Here Lies Love, and Merrily We Roll Along on Broadway. They optioned the rights to Baron’s book, brought on an additional producer and financier, Andrew Koenigsberg, and commissioned Tony-nominated composer and lyricist Michael John LaChiusa (Marie Christine, The Wild Party) to write the book, music, and lyrics. LaChiusa’s music is notoriously complex and challenging (“I like to write for Olympians,” he says). The students had to learn to time their breathing correctly, and the harmonies were difficult at first, Messer says.

LaChiusa describes the score as influenced by multiple styles: American folk songs, patriotic marches, “music of our First Nation Peoples, music our Chinese immigrants brought with them.” He patterned the show after the melodramas that were popular in the late nineteenth century, when the story unfolds. These were plays that LaChiusa says were “filled with social issues: ‘What do we do with our veterans coming back from the war?’ ‘What are we going to do about women’s rights?’ This was the theater of social conscience. Those plays went through many scenes and very epic, picaresque adventures, and many, many characters from all walks of life.”

In that spirit, LaChiusa added some characters to Baron’s narrative. Some are historical figures: the Ute chief Colorow and his family; the Black inventor Lewis Latimer, a colleague of Edison’s, who serves as the musical’s narrator. Other characters are fictitious amalgams, such as a Black family homesteading in Wyoming and a Chinese immigrant couple.

“This musical is approaching this eclipse from the perspectives of different people groups and genders and races,” says Logan Allen, a junior theatre performance major. Allen says he particularly appreciates LaChiusa’s choice to bring in Latimer as the narrator. “For me, because I am biracial, it was really cool to have that representation.”

As the 2024 eclipse approached, Baron and the producers talked about presenting pieces of the show somewhere in the path of totality. Flying out the directors and a whole cast would be prohibitively expensive, so the producers looked for a university partner—ideally in a town where the skies would be clear on April 8. Baylor was an enthusiastic collaborator. The show will not be a full production with costumes and set, but rather a concert performance of selected songs and scenes. It comes after readings for invited guests that the producers organized in 2021 and 2022 in New York; the next step toward bringing the show to Broadway will involve a six- to eight-week workshop in New York with choreography, then staging the show in a regional theater. Bringing American Eclipse to Waco benefits both the producers and audience, Brenner says. “It’s a gift to be able to share it, and we want people at Baylor and Waco to see how music can be a reflection of what’s going on in the scientific community and cultural community.” But, she adds, the team also came to town to experience the total solar eclipse in person. “None of us have seen one, and this is a show about the eclipse—how would we write about it and act and perform if we haven’t experienced it ourselves?”

The class rehearsed this week with the directing team and actors who flew in from New York. Those visitors are among a potential 100,000 guests the city of Waco will receive in the coming days.

In American Eclipse, the characters set aside their differences as they are overcome with wonder at the astronomical event. Messer says it’s a hopeful model for Monday’s celestial show. “Everyone has different perspectives and points of view, and everyone looks up and sees this gorgeous thing together. And there’s a unity in that.”