A large yellow T-shirt and a pair of cuffed, light denim jeans hung on the left wall of Texas A&M University’s James R. Reynolds Student Art Gallery. Two rainbows of tie-dye arced across the shirt’s sleeves and torso, meeting at the hemline. “Young Frankenstein,” the shirt read, above an outline of the Mel Brooks-esque creation. Young Frankenstein appears to stand atop the words “April 2016.” Next to the outfit, a small placard asked: “What were you wearing?”

“Jeans and an oversized tie-dye shirt,” the same placard read. “‘She was like a sister to me. There had never been anything like that between us. Then it was like a switch flipped in her and all of a sudden what I didn’t want didn’t matter.’ (Outfit inspired by a university student).”

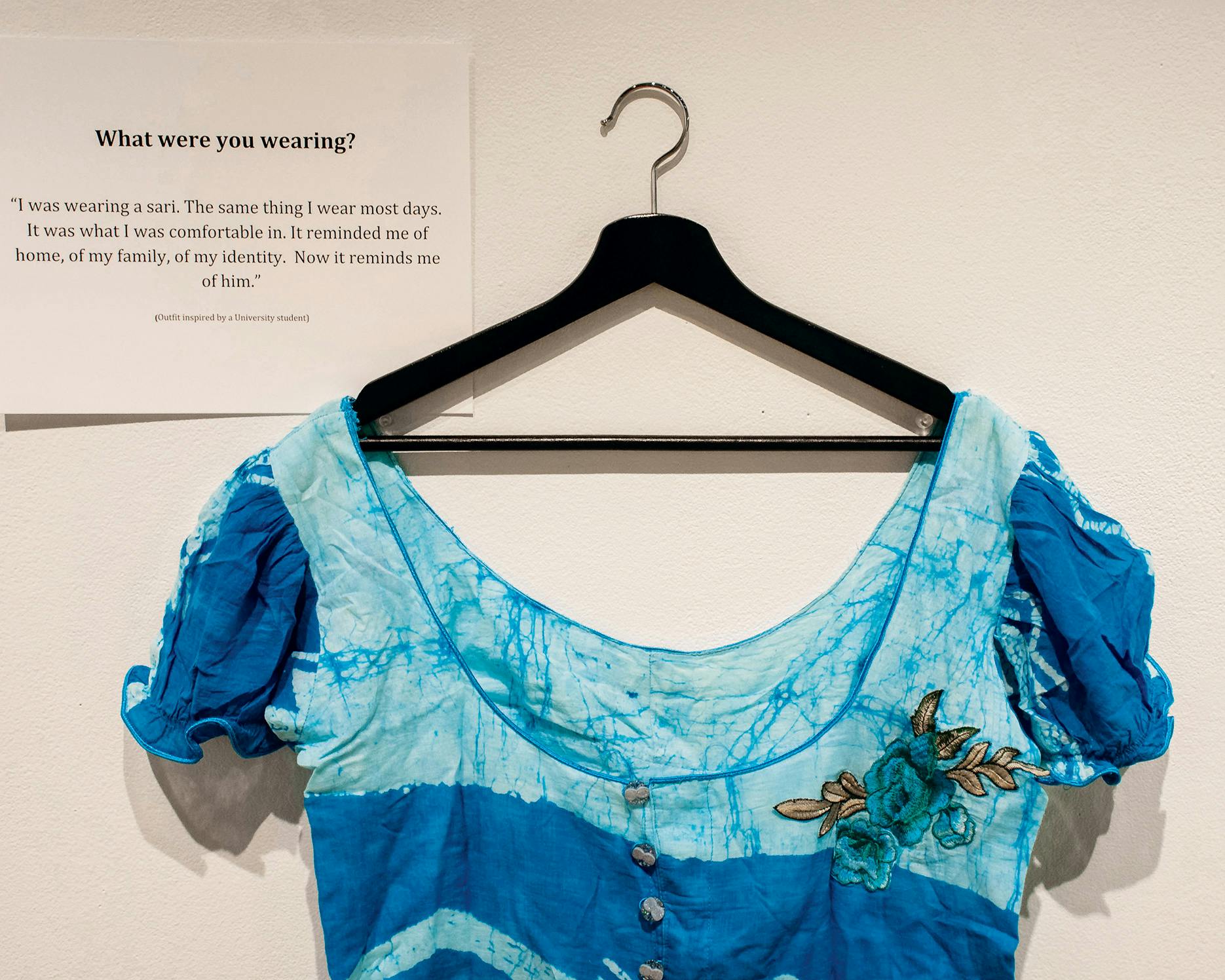

The tie-dye shirt belongs to Joshua Carley, a sophomore majoring in visual arts at A&M who is also the director of the Reynolds Gallery. While walking through the exhibit with his program advisor, Mary Compton, Carley tells me about having performed in a Young Frankenstein production in high school. Three and a half years later, he’d donated the shirt to be part of the “What Were You Wearing?” exhibit that he and other members of the Memorial Student Center Visual Arts Committee brought to A&M, as one of the stories selected for the exhibit had mentioned a tie-dye shirt. The exhibit, which ran through December 20, featured a collection of outfits—most of them as comfy casual as the tie-dye shirt and worn-in jeans—based on the stories of university students who have been sexually assaulted. Compton ironed the clothes before hanging them, to lend additional dignity to the stories they’re a part of.

“What Were You Wearing?” exhibits began at the University of Arkansas in 2013 after Jen Brockman, director of the Sexual Assault Prevention and Education Center at Kansas University, and Dr. Mary Wyandt-Hiebert, director of STAR (Support, Training, Advocacy, & Resources on Sexual Assault and Relationship Violence) at the University of Arkansas, heard Mary Simmerling’s poem “What I Was Wearing” at an Arkansas Coalition Against Sexual Assault conference. There, Brockman and Wyandt-Hiebert culled the stories of university students who had survived sexual assault, and curated representations of the outfits as described by survivors.

Since then, iterations of the exhibit have appeared around the country, including at Baylor in 2017 and at Texas A&M University-San Antonio earlier this year. Other variations, such as “What Were You Wearing, Lubbock?,” at Texas Tech University, have cropped up. In recent years, these university exhibits have become part of a bigger cultural response to sexual assault that also includes heightened participation in Take Back the Night events and performance art installations, all aiming to dispel misconceptions about assault, incite more transparent conversations about sexual violence, and provide a greater awareness of how to be an active bystander on campus.

The exhibits communicate something that’s often left out of conversations around sexual assault—that it can happen to you, or to me, and what people are wearing when it happens has nothing to do with it. Assault has happened to people who pulled a favorite sweater from their closets to have a casual night in with friends they felt safe around, and to people who deliver pizzas or lead cheers at a football game. “The exhibit peels away the misconceptions about sexual assault and exposes the inner core of a truly personal crime,” says Dr. Leslie Winemiller, an A&M biology professor who took freshmen in her First Year Experience class to see the Reynolds Gallery exhibit. “The victims’ narratives were so personal, emotional, and tangible. Students learned that anyone can be a victim, anyone can be an assailant, and it doesn’t matter ‘what you were wearing.’”

The anonymous survivors who participated in the original “What Were You Wearing?” exhibit have allowed their stories to be packaged and distributed to universities interested in hosting an installation. From there, campus-specific committees choose the stories they’ll feature and curate the clothing for those respective displays. At A&M, members of the Visual Arts Committee, like Joshua, donated pieces from their own wardrobes. And they hosted clothing drives on campus so that more students could participate in amplifying survivor’s stories. “The donors recognized the significance of their donation,” Carley says. “And understood that their clothing represented something much bigger than the article itself.”

At other academic institutions, like Sam Houston State University, students have been curating exhibits that involve the larger community’s responses to sexual assault. Nu’Nicka Epps, the assistant director for Inclusion Initiatives & Assessment in the Office of Equity and Inclusion/Title IX at SHSU, worked with students to curate an exhibit similar to “What Were You Wearing?” titled “Undressing My Voice,” in 2018. For this exhibit, instead of featuring students’ stories, a group of SHSU students led by Epps interviewed survivors at a local safe house in Huntsville. “We wanted to know how significant the clothing was to their incidents,” says Epps. “And repeated story after repeated story, it was insignificant.” The SHSU Sexual Assault Awareness Month Committee featured “Undressing My Voice” in April 2018 in the Lowman Student Art Gallery, which displayed stories from the safe house and representations of clothing the survivors said they wore when they were assaulted.

Much like at A&M, the SHSU group hosted clothing drives on campus to provide fellow students with the opportunity to participate in the exhibit. When the exhibit concluded, the executive director of the safe house washed and organized the clothing, then gave it to women and families in need at the safe house.

The campus exhibits also gave way to events that could move the conversation forward. Earlier this year, a sexual assault survivor from Huntsville addressed SHSU students at their annual Take Back the Night event, part of an international movement aimed at combatting sexual violence, particularly violence against women. The Rice Women’s Resource Center (RWRC) at Rice University hosts Take Back the Night events as well. And while “Undressing My Voice” appeared on SHSU’s campus, RWRC codirectors Mackenzie Kubik and Chloe Wilson were looking for ways to revitalize Take Back the Night to increase student participation. In years past, the RWRC made event posters themselves or encouraged participants to bring them with them. But in 2018, Kubik and Wilson decided to host a poster-making event prior to the march. “We felt that it would help individuals ease their nerves of having difficult conversations about assault, participating in the march, or confronting difficult personal experiences,” Kubik says.

Just a few months later, Texas Christian University featured a new installation, commissioned by the university-affiliated gallery Fort Worth Contemporary Arts, that examined the role of gender in the contemporary urban experience. The interdisciplinary artist Alicia Eggert, who’s also an assistant professor of studio art and sculpture program coordinator at the University of North Texas, created the group exhibition project “You Are Her” in conjunction with the exhibit “Flâneuse.” Eggert printed the phrase on two large red-and-white signs designed to look like “Do Not Enter” or “Wrong Way” road signage while playing on the phrase “you are here.”

To accompany the “You Are Her” signs, Eggert created red, yellow, and black exclamation-point logos. “In the road signage world they’re called ‘incident signs,’” Eggert says. “They typically indicate that there’s danger ahead or an incident has already occurred in that general vicinity.” While working on the project, Eggert learned from the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network that 23.1 percent of female university students experience rape or sexual assault during their college experience. Most of these assaults occur during a student’s first year. So Eggert did the math—23.1 percent of incoming freshmen at TCU represented 240 students.

Eggert then decided to use the signs for a performance art piece, where performers stood on campus with signs harnessed to their shoulders and covering their faces. They did so for a collective 240 hours. On the opening night of Eggert’s installation, the performers, some of whom found the way the signs hung in front of the faces and blocked their view to be disorienting and upsetting, faced an apartment complex. She notes that several men shouted at them repeatedly from a balcony. “You’re hot,” they bellowed. “Nice tits.”

Whether it’s clothing displayed on a gallery wall, posters produced in a courtyard, or performance art, these artistic responses to sexual assault make a potent statement that’s somehow both passive and active. The clothes are just hanging there. The performers stood there. Yet many viewers had powerful reactions to the art. After “Undressing My Voice” at SHSU, for instance, many students “requested support services after feeling supported and empowered to speak up about their personal experiences,” Epps says. And Carley says his mom had a visceral reaction to seeing her son’s shirt hanging on the wall. “It wasn’t until then that I realized the impact my own personal clothing could have,” he says.

That also became clear to Kayla Allison, a then-student at Texas A&M who posted a photo project in summer 2018 that included an image of her lying on the rim of a well-known university fountain with the words: “We Regret Your Displeasure”—a reference to an email an A&M administrator sent to a student who reported that she’d been raped by a member of the Aggie swim team—written on her legs in red lipstick. Afterward, Allison received comments like: “I agree with your message. I don’t agree with how you’re communicating it.” And her inbox filled up with stories of sexual assault survivors who felt what she did—that this outlet helped her take power back after her own experience with assault.

A kaleidoscope of brochures, hung on the wall opposite the yellow shirt at A&M’s Reynolds Gallery, provided resources for reporting assault, preventing harassment, and learning to be an active bystander. Nearby, gallery visitors were invited to sketch their own shirts on small pieces of paper that hang on a clothesline. “We see you,” one shirt read. Nearby, another shirt read: “It’s not your fault.”

- More About:

- Art

- Texas Tech

- Rice University