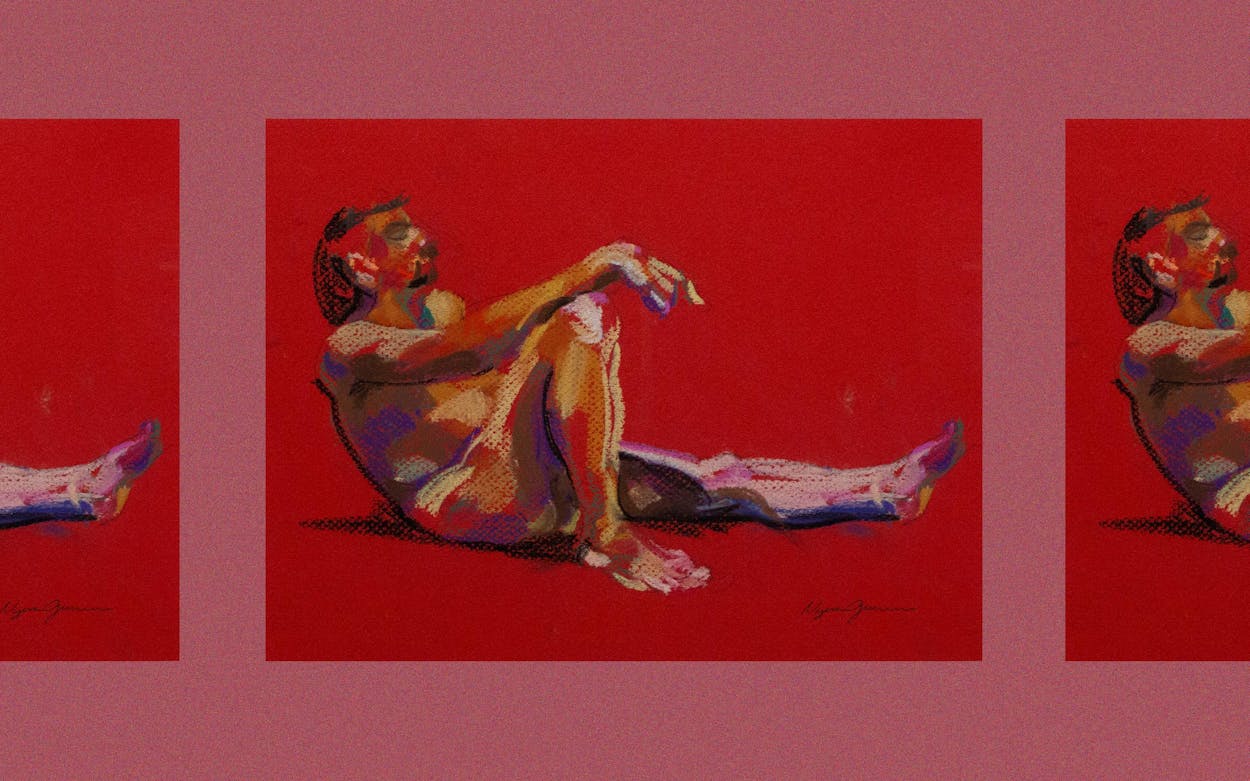

Nurse practitioner and author Emily Medley entered a concrete-floored studio on a cold February day and took her clothes off. She centered herself upon a platform heaped with soft blankets and pillows, ready to be drawn nude. As ambient tunes played during the next two hours, a spotlight illuminated her nearly fifty-year-old body while studio artist Nyssa Juneau transferred her figure onto a piece of green pastel paper, a shade that just happened to be Medley’s signature color.

As Medley recounts it, the surreal, cerebral, and private experience resulted in her feeling like an artist, too. Designed to be a birthday gift for both herself and her husband, who had it framed in “the most expensive frame possible,” the portrait was also a way of memorializing a liminal period of life. “I wanted to celebrate a time of being both young and old,” says Medley, who describes herself as “technically old now,” but still as young as she’ll ever be.

Milestone birthdays, experiments in self-love, and bucket list achievements are common reasons people sign up for the Send Nudes Project, a collaboration between Juneau and the community art nonprofit Art League Houston, where Juneau teaches drawing classes. The initiative aims to explore the nude figure in the context of art history and modern counterculture—in a safe, consensual space, without photographs. After the two-hour session with Juneau, currently bookable through February 15, the subject leaves with a hand-drawn work done in charcoal or pastels.

Juneau has drawn numerous nude figures in a career that formally began at Louisiana State University’s School of Art, where she earned a fine art degree. She’s still fascinated by the way the body’s anatomical markers fit together in space, almost like puzzle pieces—just as other artists have been for centuries. (Famously curious, Leonardo da Vinci dissected around thirty cadavers in order to accurately represent the human figure in his drawings, paintings, and sculptures.)

Sharing images of one’s own nude body also has a long timeline. Many believe that the Venus of Willendorf, a small stone figure from around 25,000 years ago, was meant to represent a fertility goddess; some historians have suggested that it might be the oldest example of someone rendering themselves nude. Juneau’s favorite nude selfie, though, is Sarah Goodridge’s “Beauty Revealed,” a miniature watercolor painting of the artist’s exposed breasts that she sent to her lover, Daniel Webster, in 1828.

Centuries later, sending nudes is still a thrill. A recent survey of two thousand respondents revealed that 78 percent of women and 82 percent of men have intimate portraits of themselves saved on their phones. One third of Americans have sent nudes, with 73 percent of those doing so at least once a month. But as Juneau points out, the practice of sharing naked photos today raises concerns: bullying, revenge porn, sextortion, and jeopardized employment are consequences that can affect anyone whose image is shared with the wrong person. As Juneau says, the Send Nudes Project is unique in that it allows people to experiment with a time-honored art form while regaining the privacy and ownership that can’t be assumed in the digital age.

Former Send Nudes subjects, all Houstonians ranging in age from their late twenties to early seventies, concur that the one-on-one experience felt safe and warm (both figuratively and from the space heaters), and was less intimidating than posing nude for an entire classroom of art students. “She did everything she could to make me feel comfortable,” says Alli Villines, who, like Medley, had her portrait drawn on the cusp of a big birthday. As a musician, actor, voice coach, ukulele tutor, and co-owner of a puppet company, Villines lives by schedules, and appreciated getting the preliminary email outlining what would happen and what she should bring. “I love to have the details, especially for something I was really nervous about,” she says.

As for many past participants, being drawn nude was a clear and specific desire that Villines wanted to experience in her lifetime. The yearning first struck her twenty years ago, during her first year in college, where she passed by student-drawn nude portraits on display in the hallway to her band class. “I wish I could do that,” she distinctly remembers thinking, but because her classmates might see, and because she was raised in a conservative home where modesty was encouraged, she suppressed the desire until she saw an Instagram post about the Send Nudes Project.

“I was thirty-nine and about to turn forty,” she says. “And I was definitely on a kick about honoring my body, which got me through a pandemic . . . and which is getting older and changing. All of those things conspired together to make me sign up and do it.”

She later told her mom, who texted back with the wide-eye emoji. Her husband now has it displayed on his side of the bed, and described it as powerful when he first saw it. “When I look at the portrait, I just have pride,” says Villines, who views the artwork as a way of honoring her body and the buried wishes of her nineteen-year-old self.

Nude modeling was also on Christopher Buffamante’s bucket list. A film actor, model, writer, professional Hula-Hooper, dancer, “and some other things as well,” Buffamante decided to do it because he didn’t know Juneau and therefore “had nothing to lose.” He describes himself as extroverted and brave. As he says, “Whenever you go through a lot in life, you don’t really care what people think of you.” When he did it last year at age thirty, it was a good time because he was at his peak, but now, a year later, he’s at a different level, he says. “My body looks even better, so it’s a great idea to do it again.”

Other participants opted for a Juneau portrait specifically because their bodies depart from contemporary chiseled prototypes. A family nurse practitioner and mother, Ginger Patel signed up for Juneau’s introductory drawing class at Art League Houston last year as a way of investing back into herself. She liked Juneau’s preference for drawing all types of bodies, including those that look more like Renaissance figures than Instagram fitness models. She points out that when you look at famous artists’ sketchbooks and see their work in museums, you see bodies that look more like hers, that have stretch marks and weigh more than two hundred pounds.

Patel wanted to be a part of normalizing larger bodies in the age of Ozempic. Even though there was initial awkwardness because of the student-teacher relationship she has with Juneau, she eventually melted into the session by listening to her favorite internal medicine podcast while Juneau drew. For Patel, the experience felt like being part of “real, tangible art that happens right in front of you, but you also get something at the end of it that’s beautiful.”

Juneau says it’s important to her that those who pose for her feel a sense of dignity. She’s aware of the vulnerability required, and so she tries to create an atmosphere where comfort is paramount (in part so that she can draw a better portrait, too). “I hope that everybody sees that because I think everybody’s beautiful,” Juneau says. To her, comparing bodies is “like comparing one flower to another.”