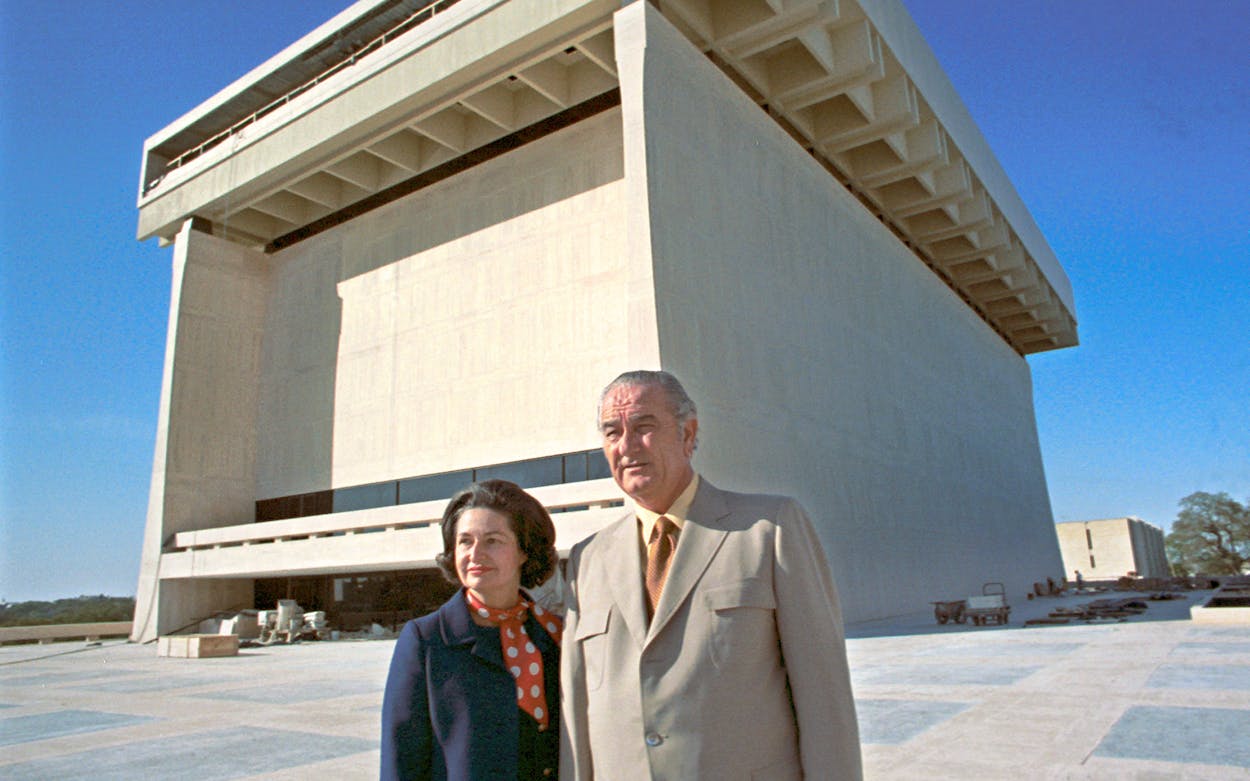

On May 22, 1971, the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library at the University of Texas opened its doors for the first time. The library now welcomes more than 100,000 visitors per year, including researchers who travel from across the country to use the facility’s extensive archive. In addition to 45 million pages of historical documents and nearly seven hundred hours of the president’s recorded phone conversations, the trove includes the pen Johnson used to sign the Voting Rights Act into law—and the pants he wore at his second inauguration. (History buffs will remember that LBJ was famously fastidious about his pants.)

The Johnsons hired Neal Spelce, a longtime Austin broadcast journalist and family friend, to plan the library’s dedication ceremony. It was a massive undertaking; for five months, Spelce and his staff worked around the clock to organize the event for three thousand guests. Security was tight, as protests raged over the Vietnam War and Johnson’s role in it.

On the big day, everything went off without a hitch—well, almost. In this excerpt from his new book with Thomas Zigal, With the Bark Off: A Journalist’s Memories of LBJ and a Life in the News Media, which the Briscoe Center for American History and UT Press will publish in September, Spelce remembers the ceremony, including a few memorable moments along the way.

May 22 was an unexpectedly windy day, and we were afraid it was going to rain, but the weather turned out to be beautiful. The male guests were dressed formally in suits and ties and the women in their finest, because it was a one-of-a-kind moment in the history of our nation.

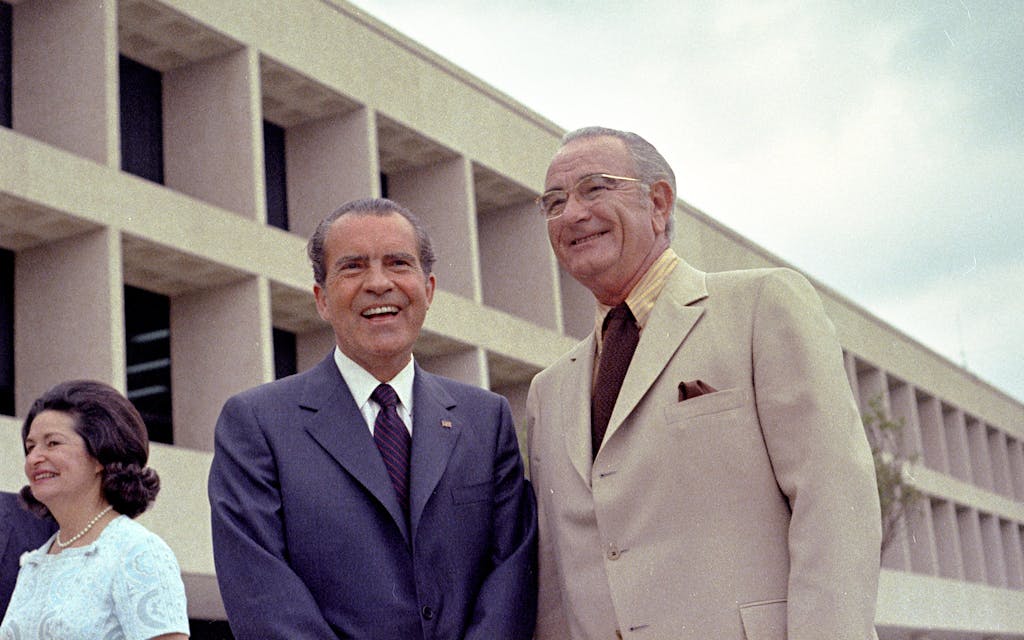

As the ceremony began, it was my job to walk with LBJ and Richard Nixon and guide them through their paces, silently gesturing for them to turn here, descend these stairs, stop there and wave. It shook me a little when I realized that walking right beside me was the Marine officer who was carrying the football, as it’s called, the black briefcase carrying the launch codes for our country’s nuclear weapons. That briefcase goes wherever the president goes, and it contains the instructions on what the president should do and where he should go in case of an emergency situation or attack.

The Marine’s lips weren’t moving, but I heard him saying, “Turn left, Mr. President. Go straight. There are steps ahead, so be prepared to take those steps. When you get to the top, here’s what’s going to happen.” The Marine and I hadn’t discussed or coordinated where I was leading them, but to the public, it looked as if the presidents were well rehearsed and striding with confidence and grand purpose. There were no blunders. The Marine and I had done our jobs.

The Reverend Billy Graham delivered the opening invocation. He was LBJ’s spiritual adviser and a key part of his life. The president listened to him. When LBJ was buried two years later at the Johnson ranch, Billy Graham presided over the rites at the president’s request. I don’t know that observers would’ve called Lyndon Johnson a religious man. He attended church, but he wasn’t someone who wore religion on his shirtsleeve. He respected ministers and the clergy, and he would include their voices in the rollout of his various social programs, especially ministers in the Black churches.

In his remarks, President Nixon was very gracious in his praise of the former president, even though they were political enemies. That day, the two men reached across partisan lines as if to say, “You were the president, I am the president, we understand each other and what we’ve both gone through in this job.”

LBJ’s own address perfectly summed up the new presidential library: “It is all here: the story of our time—with the bark off. This library does not say, ‘This is how I saw it,’ but this is how the documents show it was. There is no record of a mistake, nothing critical, ugly, or unpleasant that is not included in the files here. We have papers from my forty years of public service in one place, for friend and foe to judge, to approve or disapprove. I do not know how this period will be regarded in years to come. But that is not the point. This library will show the facts—not just the joy and triumphs, but the sorrow and failures, too.”

I had heard President Johnson rehearse his remarks the day before the dedication ceremony, when he said to me, “Let me read this to you, Neal, and see what you think.” He was walking into the restroom as he spoke, and in true LBJ fashion, he unzipped and began guiding his stream while he read those words aloud from an index card. By that point, nothing surprised me about our informal meetings.

After all the remarks were concluded on the platform, I accompanied Presidents Johnson and Nixon as they walked in front of the fountain and then went up the long slope of stairs to the plaza above. It was my idea that when they reached the plaza, they would wave to the audience below while the Longhorn Band was playing “The Eyes of Texas” and people were clapping, and we’d turn on the silent fountain for the first time in public. When we cued the fountain, a beautiful plume rose into the air and the strong winds blew the cascading water over the audience, drenching all of them dressed in their finery, women and men alike. It wasn’t exactly a gully washer, more like a soft rain.

At that historical juncture, it was hard for me to disagree with what Lyndon Johnson had said a few months earlier: “If there’s any way to f— it up, Spelce, you will.”

It was a faux pas, but it quickly became a laughable moment because everyone was in an upbeat mood, enjoying the celebration, and they had great respect for LBJ and his family. Fortunately for me, The Man didn’t put me in a headlock after the dedication was over. We turned off the fountain once we saw that it was spraying the audience, and when the guests eventually made their way into the library and began attending other functions, we turned the fountain back on so that everyone could see the cascade in all its glory from a distance. It really is a great fountain, with travertine marble containing the pool of water. It would have been a majestic surprise if the wind hadn’t flared up.

Frank Erwin, chairman of the University of Texas System Board of Regents, was a force of nature. Highly controversial and unpopular with UT students because of his hardline opposition to student demonstrations, he was a git ’er done guy. When somebody in power needed something, he made it happen. He was instrumental in persuading the university to approve of, and pay for, the LBJ Library. And he’d found the money to make the Hardin House renovation possible. His imprint was on everything at the dedication.

Our team met with “Chairman Frank” on a regular basis to go over what we were planning for the ceremony, what we needed a decision on, and a number of issues that required discussion. At one point, as the date was quickly approaching, Frank said, “You know, Neal, everybody will want a drink when the program is over.”

Frank Erwin was no amateur when it came to drinking.

I said, “Mr. Chairman, I’m sorry. This is university property and it’s forbidden by law to serve alcoholic beverages in a university facility.”

He looked down his Ben Franklin reading glasses at me, paused, and said, “All right, Neal. I understand.”

I went on to say, “Think of the publicity. If we go through all this planning and have a great ceremony, Mr. Chairman, and someone comes back and says we’ve broken the law, or if someone gets arrested, we’ll never live it down.”

“Okay, fine, Neal.”

I thought I’d won the battle. But on the day of the ceremony, shortly after the fountain sprayed everybody and the show was over, portable bars were wheeled out with full whisky bottles stacked on top, and formal bartenders started pouring drinks. Everywhere I looked there was another bar, and another. I didn’t know if Chairman Frank had used his own nickel or the university’s nickel. It wouldn’t have surprised me either way.

I couldn’t do anything about it, of course. When Frank saw me staring at him, shaking my head, he grinned at me with a Scotch in hand. I thought, “Erwin, you son of a b—.”

In keeping with LBJ’s tradition at the ranch, Texas barbecue was served to guests sitting at long tables arranged underneath striped awnings that were rippling in the wind: Henry Kissinger, Dean Rusk, Barry Goldwater, William Westmoreland, future Watergate figures Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, Julie Nixon Eisenhower and David Eisenhower, and three thousand other VIP attendees. It was quite a feast, with a large and cheerful family atmosphere, the kind of celebration the Johnsons had always enjoyed, and the perfect conclusion to nearly four years of construction and six months of intense planning for that day.

One of my most enjoyable moments at the dedication was meeting actor Gregory Peck. He and his wife, a former Italian journalist named Veronique Passani Peck, were close friends with the Johnsons. The Pecks returned to Austin a time or two after that, and on one occasion I complimented him on his role as Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird.

He was gracious, saying, “Thank you very much,” and he confided a story about Harper Lee, the author of the novel. “She was on the set from time to time,” he said. “I remember walking along a sidewalk for a quick shoot, and after we finished the take, she came over and said, ‘Mr. Peck, watching you do that scene, I thought I was seeing my daddy.’”

The character of Atticus Finch was based on her father, an attorney in the Deep South.

Gregory Peck told me, “I was overwhelmed. I really thought, ‘That’s the highest praise an actor can get.’” And then she went on to say, “Your stomach pooches out just like his did.”

He looked at me with that handsome smile and said, “That’ll bring you down a notch or two.”

For me personally, the library dedication had been a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I had rubbed shoulders with university leaders, nationally acclaimed architects and builders, law enforcement professionals, the staffs of two American presidents, and hundreds of generous volunteers. When the dedication was finally over, I felt incredibly proud of the major role that my team and I had played in one of the significant historical events of the twentieth century. But after months of nonstop adrenaline rush—day after day, around the clock, especially in those final weeks leading up to the ceremony—I was completely spent. A skinny guy to begin with, I had lost ten or fifteen pounds because of the constant energy the work required. My mind never slowed down. I was always thinking, “What about security? What about the food? Have we checked the sound system? What about the weather?”

As the barbecue was winding down and those three thousand guests began to leave the grounds, President and Mrs. Johnson went upstairs in the library and took their shoes off to relax and decompress. I can’t remember what time Sheila and I left, but it was dark when we got home. Suddenly the adrenaline was gone, after five months of stress, and I just collapsed. I was wiped out, but I felt satisfied and tremendously relieved.

The euphoria didn’t last long. There was work still to be done. My team and I returned to the library the next morning, a Sunday, to help clean up and make sure everything was in its proper place. There was also the Hardin House and a tremendous amount of tidying needed there. One of the volunteers, former KTBC cameraman Gary Pickle, a good friend of mine to this day, recently reminded me that he was in charge of the rental cars. They were loaners, fleet vehicles, fancy cars. As he said, “Dignitaries just left them where they were. We had to wander around Austin picking up cars.”

In the days following the dedication ceremony, I received thank-you notes from LBJ, Mrs. Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Spiro Agnew. I was so grateful for those personal notes that I’ve preserved them behind glass for fifty years. They’re hanging on a wall in my home office.

LBJ wrote, “Dear Neal: You gave us a successful beginning to what we hope will prove to be a worthy project. The good memories of May twenty-second are going to stay with us always, and whenever we turn our thoughts to that day, we are going to be thinking of you, too, with gratitude and admiration. You did an outstanding job arranging everything for the dedication ceremonies, tying a thousand and one details together during days we know were never long enough.” He added, “Mrs. Johnson and I thank you on behalf of all the guests who were here, and most of all, we thank you on our behalf for a perfectly planned day.”

Ever the warm and gracious lady, Mrs. Johnson wrote, “Dear Neal: I know you must be exhausted, but I hope you are happy, because the Dedication couldn’t have been better and you deserve a lion’s share of the credit. Everyone has been singing your praises and if you’re not careful you’re going to be putting on every dedication that’s held in Texas or any other place for that matter! To say we couldn’t have done it without you is an understatement, but I’m sure you have heard every superlative by now. Please know that Lyndon and I will never forget all you did and will be forever grateful.”

She signed her note, “Lady Bird.”

Excerpted with permission from With the Bark Off: A Journalist’s Memories of LBJ and a Life in the News Media, to be published by the Briscoe Center for American History and the University of Texas Press in September 2021.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- Books

- LBJ

- Austin