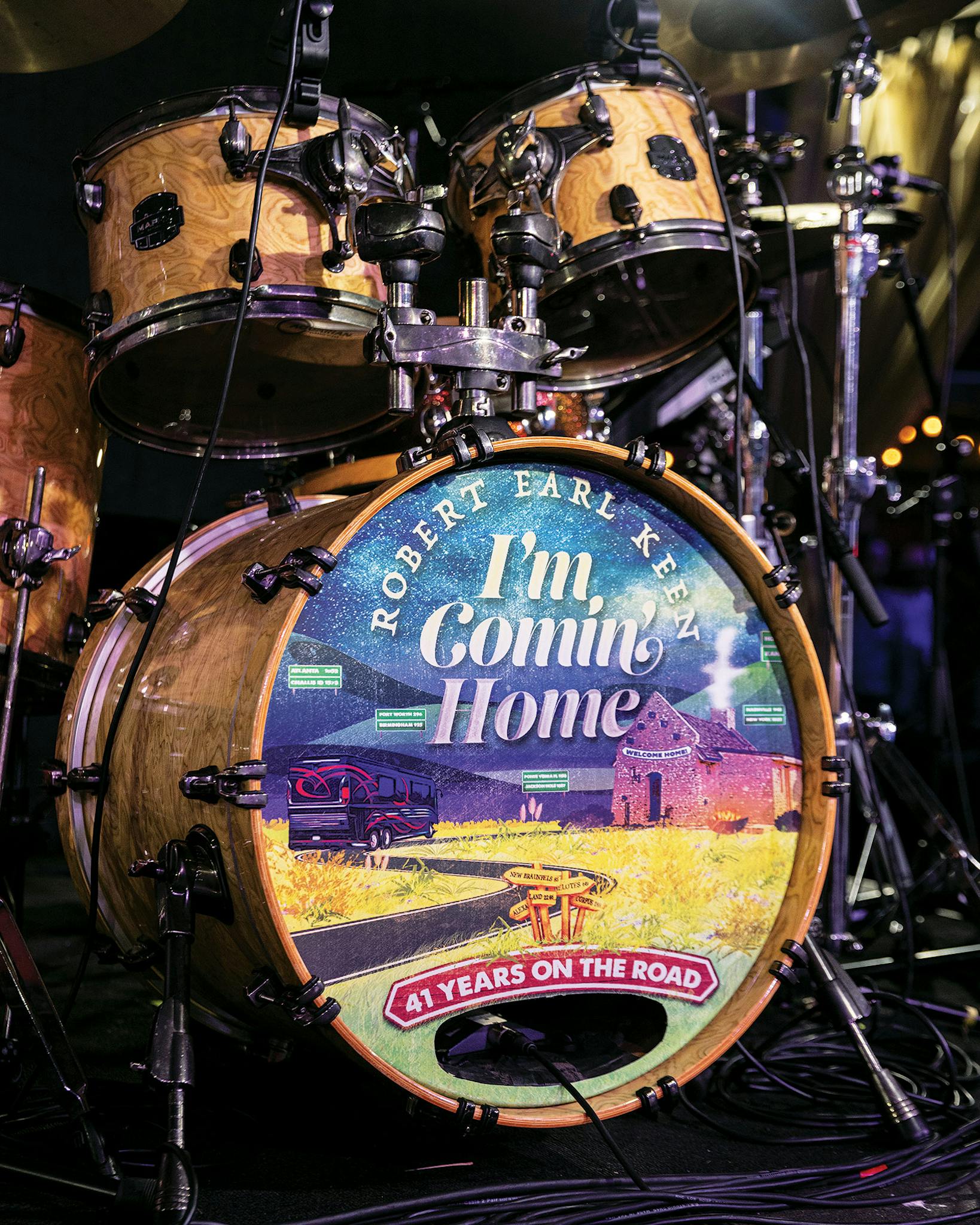

Over Labor Day weekend, Robert Earl Keen’s six-month-long “I’m Comin’ Home” tour ended with a grand finale at his musical home: John T. Floore’s Country Store. The Helotes honky-tonk and tamale-serving cafe was the perfect backdrop. Before the tour kicked off, Keen had announced it would be his last. Now, for three consecutive nights, Keen played his final shows before quitting the road for good. It was an exuberant, tearful affair. Thousands of fans sang along to their favorite Keen-penned tunes. It was a party that many, me included, wished would never end.

Every night the backstage vibe felt increasingly giddy, a sharp departure from the mood earlier in the tour, when a run of bad luck (which included the tour bus catching fire) had added a layer of stress to an already-grueling schedule. But now that the end was here, it was time to relax and celebrate.

Floore’s was packed with diehards, including a woman named Diane, known affectionately as “the chicken lady” by Keen’s crew, because for years she’s showed up to Keen shows with home-cooked meals for the band. Quite a few fans snatched up tickets for all three dates. Seeing the same faces night after night made it feel even more like a family reunion.

For some, it actually was a family gathering. West Texas state representative Brooks Landgraf was there with his wife, Shelby; their seven-year-old daughter, Hollis Rose; and Shelby’s parents. “Robert Earl Keen has meant so much to Shelby and me,” Landgraf told me, as he held his daughter in his arms near the front of the stage, “and we wanted to make sure Hollis Rose had a chance to see him before he quits the road.”

The run of shows wasn’t completely hiccup-free. It rained hard Saturday evening, and many in attendance sported ponchos and even trash bags to stay dry. On Sunday, right before the band was set to take the stage, the soundboard suddenly and mysteriously shut down. After thirty minutes, Brett Brock, Keen’s tour manager, got everything back up and running, and the rest of the night went off without a hitch.

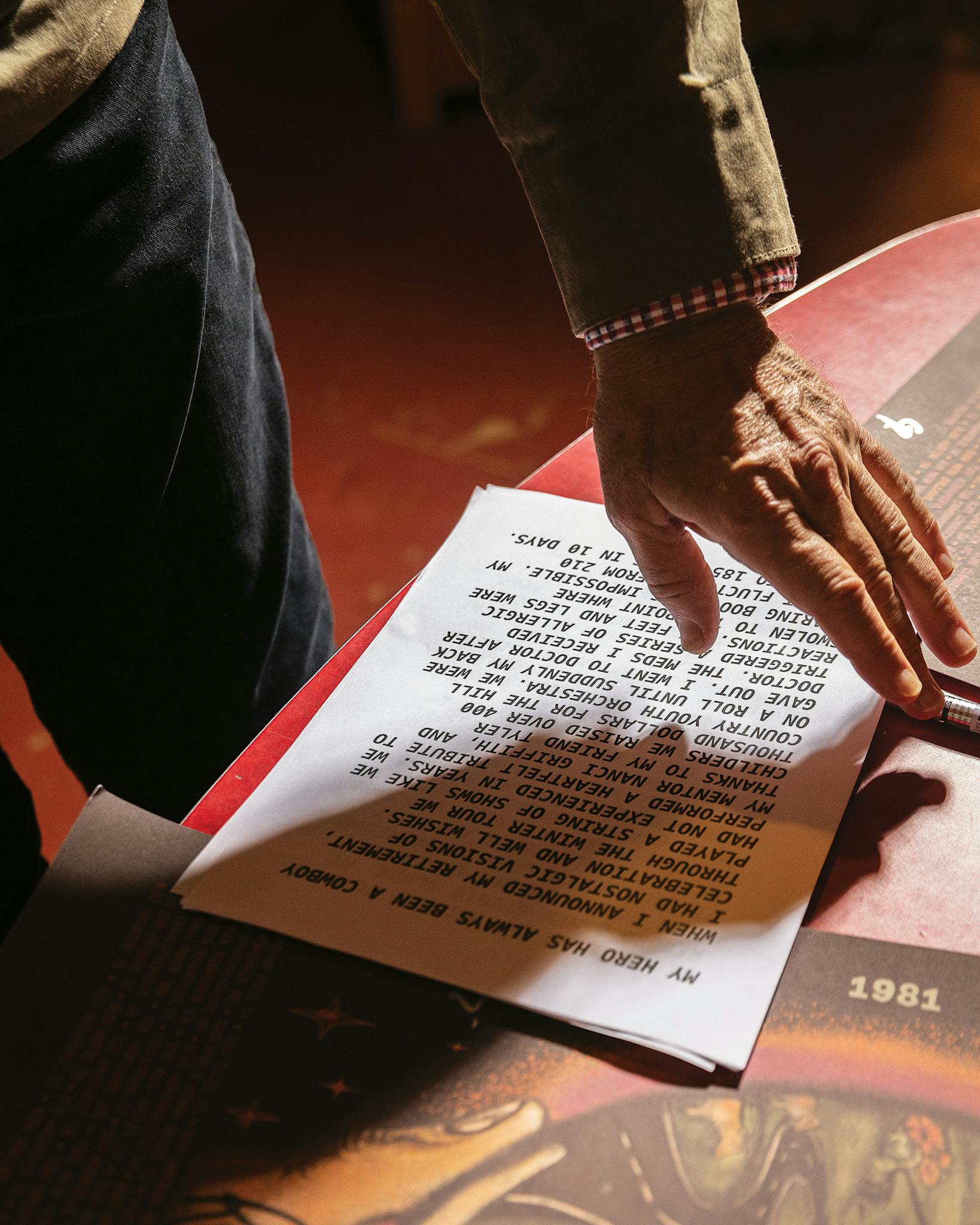

Some of the highlights included Eric Church’s all-acoustic set to open Saturday night, as well as the other opening acts, which included James McMurtry and David Beck’s Tejano Weekend. Brendon Anthony, the director of the Texas Music Office, read a proclamation from the state government honoring Keen’s artistic contributions. But the pinnacle of the weekend might have been Keen’s moving farewell speech. He explained that he was inspired to go out while he still enjoyed playing, much like his rodeo hero, Phil Lyne, who had retired after winning a couple of all-around world championship titles in the early seventies. Keen and many in the audience were moved to tears when Lyne came out to stand beside Keen at the end of the speech. (Lyne’s son-in-law J. B. Mauney, arguably the world’s best bull rider, was on hand as well, rooting them both on from backstage.)

The band played more than two hours every night. They covered a wide swath of Keen’s expansive catalog, serving up songs that went all the way back to his 1984 debut album, No Kinda Dancer. The crowd danced jubilantly, and Floore’s broke its record for most beer ever sold in a single night—by a lot. While it was certainly a raucous affair, the pervading feeling was one of gratitude, both from the crowd and from the stage. Keen’s shows have always included a lot of interplay between the artist and the fans. (Shouting “I ain’t never goin’ back” on “Gringo Honeymoon” never gets old.) Keen, a Texas A&M graduate, has compared the crowd at his shows to the Aggies’ fabled “twelfth man,” and he says the audience’s engagement can make the difference between a mediocre show and a great one.

Those final shows at Floore’s were all-timers. A worthy send-off for a Texas legend.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music

- Robert Earl Keen

- Helotes