This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Cactus Pryor, disguised as General Hans Christoffersen of the Danish Royal Air Force, walked into the Knights of Columbus Hall in Sealy, Texas, and began kissing the hands of the ladies. They were enthralled, and admired without suspicion the big, gaudy medal on his uniform that he had bought in the basement of Scarbroughs department store. Their husbands gathered around him as well, pumping his hand as he bowed slightly from the waist.

“How you doin’, General?’’ one of them asked him.

“Vell, I am better until I eat,” he replied in the Henry Kissinger accent he had adopted for the evening. Pryor asked naive questions about the Alamo, about oil and ranching, and was politely answered. No one seemed to think it odd that the main speaker at the annual awards banquet of the Austin County Soil and Water Conservation District was a representative of the Danish Air Force.

“Vut kind uff horses do you raise on your ranch?” the general asked a big, flush-faced man with horseshoes embroidered on his necktie.

“Well sir, we have quarter horses mostly.”

“Excuse me?”

“Quarter horses. You know, cow horses.”

“You mean you breed the horse vis the cow?”

“Oh . . .” The rancher looked down at the general with a kind of pity. “No sir, you see . . .”

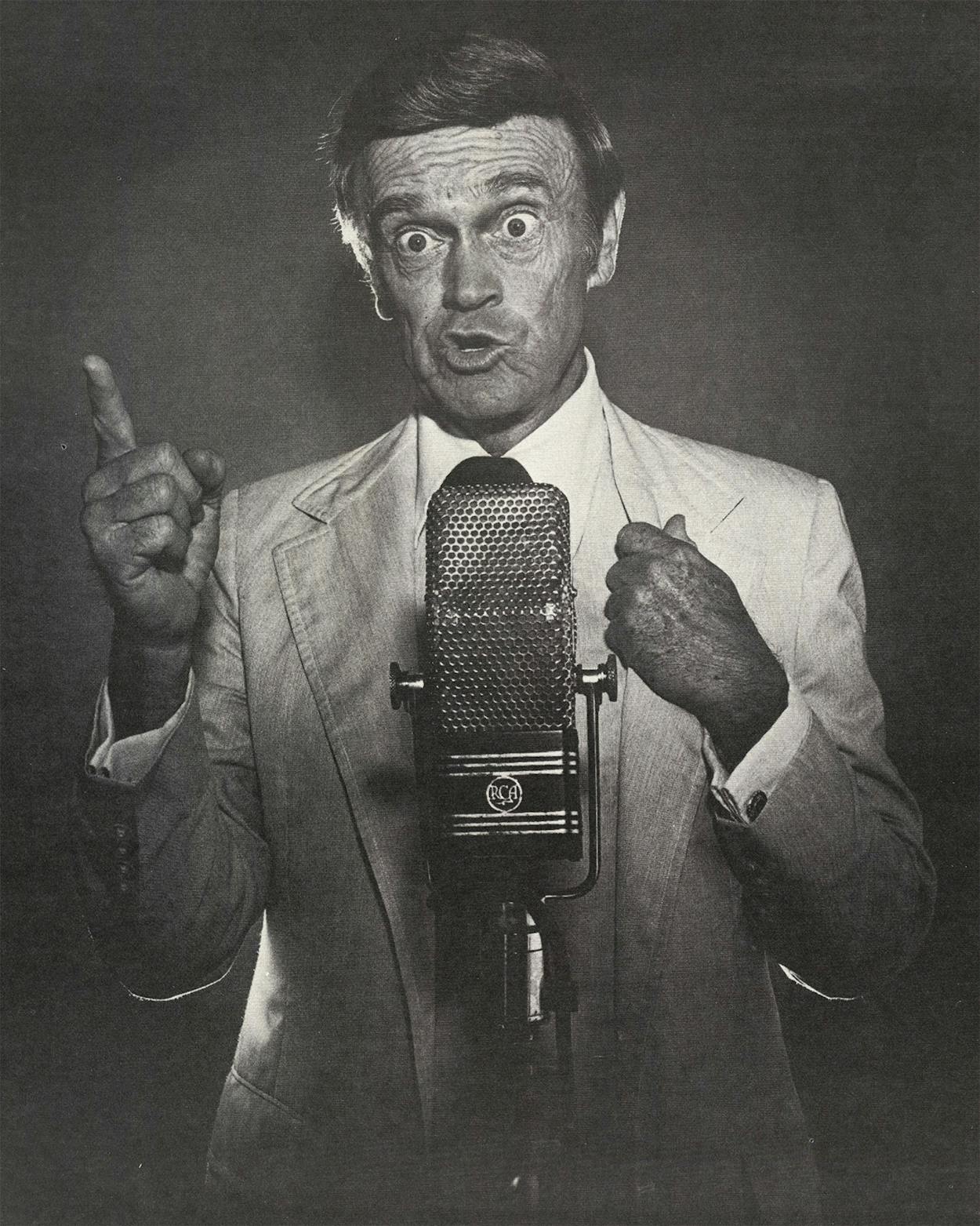

Perhaps half a dozen people were in on the joke. The rest filed by to be introduced. It surprised me that no one recognized Pryor, the widely known after-dinner speaker, political satirist, and media fixture, but it had been a while since his fame had enjoyed wide currency, when he had served as Lyndon Johnson’s court jester. Except for the uniform, he was not in disguise, unless one counted his toupee. Still, he stood out. His face was more expressive than those of the ranchers and agribusinessmen around him—a calm, indolent, slightly reptilian face that put me in mind of an alligator snoozing motionlessly on a riverbank.

I hung back, eavesdropping, and watched him work. He convinced a balding judge that he should try reindeer manure as a hair restorative, asked a woman to define coonass for him, and got a priest to admit that they had met one another in Denmark.

Someone had punched the polka button on a home organ that was lit up like a jukebox, and the hall reverberated with ancestral rhythms. There was a barbecue buffet and afterward some harmless speechifying. Pryor sat at the head table, cutting his meat in the Continental manner and making small talk with district board members and with the dapper young savings and loan officers who were there to present awards in such categories as Outstanding Conservation Farmer and Rancher and Outstanding Agriculture Extension Leader.

The first award went to a “progressive farmer and rancher” who, the citation noted, had “invented the first Coastal Bermuda grass sprigger.” The recipient walked up to the podium, sore and weathered and unreadable. His wife, who was with him, was missing an arm. Together they held up the plaque and posed awkwardly for the photographer of the Sealy newspaper. It was plain that what was being honored was not so much the invention of the Coastal Bermuda grass sprigger as a lifetime of doggedly wresting sustenance from the land. Pryor leaned forward with his elbows on the table. His Danish Air Force officer might have regarded this scene as an amusing set piece of Americana, but Pryor did not bother with the fine-tuning of the character. He was plainly moved, and it seemed to me he was already tired of playing the role of an outsider, that he had no more patience with his own artifice. People had told me that if there were any justice in the world, Cactus Pryor would have been a star long ago, but I was convinced that he had not so much “missed” stardom as he had unconsciously avoided it. Here, at this rural Texas barbecue, he seemed content—as perfectly adapted to his environment as a creature can be.

General Christoffersen was introduced after the awards ceremony, as the paper plates were being stacked and passed to the ends of the tables. The biography that Pryor had given the master of ceremonies pointed out that the general was “a leader of the Danish underground during World War II,” “an author of some note,” and “regarded as a keen wit in a nation famous for its sense of humor.”

The audience accepted this nonsense in good faith. Pryor reached the podium and after the applause had died down began relating a series of one-liners about his impressions of America.

“I learn from your television that in this country you haf hens that lay the eggs vis panty hose in them. I see also that you are not free to squeeze the tissue. By Gott, in Denmark ve are free to squeeze the tissue anytime ve vant!

“Ven I come from Vashington on the airplane, across the aisle is sitting from me a man from your state. I make the greatest mistake of my life und ask him to tell me about Texas. Ven he finish I understand vy you vear the high boots down here.”

The audience found all of this funny, but they were also somewhat bemused at the idea of listening to a Danish general do stand-up comedy. Nevertheless, when he was finished they gave him a standing ovation. They wanted him to feel at home. General Christoffersen bowed and returned to his seat.

“It gives me great pleasure,” the emcee then said, “to introduce another great after-dinner speaker, Mr. Cactus Pryor!”

The man in the uniform rose again to speak. There were gasps at first, and then, as it dawned on the audience what was going on—that they were now face to face with their own gullibility—there was widespread laughter that sounded both embarrassed and relieved.

“I’d just like to say howdy, friends and neighbors, and hook ’em horns. My name is Cactus Pryor, and the closest I’ve been to Denmark is a bottle of Tuborg beer.”

I’m a comic,” Cactus Pryor had told me on the way to Sealy. “Some guys are very sensitive about that word, especially on the after-dinner circuit. They want to be thought of as ‘humorists.’ I don’t think that—politically, for instance—I’m that profound. If I can bring out the irony of the situation, the hypocrisy, and get a laugh, that’s my contribution. I can’t compare myself to Will Rogers or whoever.”

Pryor might fit more easily into a tradition if his career were not such an eclectic affair. He is, or has been, a speaker, actor, newspaper columnist, radio and TV personality, singer, pitchman, toastmaster, roastmaster, director, sports commentator, kennels owner, and screenwriter. For everyone who might care to force a comparison with Will Rogers, there is another who would suggest a closer affinity to Bob Hope, and still another who would dismiss the whole question by simply writing him off as a buffoon, the sort of washed-out celebrity that local radio and TV stations keep on the payroll as mascots.

And it is true one could receive that last impression, based on a cursory glance at Pryor’s media presence. It’s unfortunate that the least interesting of his talents are the most relentlessly aired. One turns on the tube in Austin and sees him huckstering, in his low-key manner, for some Western-wear shop or poor-boy art fair, or performing salacious monkeyshines when Suzanne Somers’ name is mentioned during a promotional announcement for the upcoming season. Neither does his newspaper column, syndicated in seven papers in Texas and one in Louisiana, show him off to much advantage. It consists of maybe five or six one-line jokes, usually about political issues and almost always a beat or two away from being funny.

But those who have seen him perform in person know how brilliant he can be, and how the same jokes that would seem isolated and eccentric in his newspaper column can suddenly blossom, little flash-frozen organisms coming to life in the saline bath of his personality.

I’d heard it said that Cactus Pryor is a “Texas institution,” but I never gave the overworked term much thought until last February when Pryor was honored by the Headliners Club, the Austin journalism society that every year conducts a “roast” of some celebrity or other. Pryor had written and emceed these events for twenty years, lampooning the antics of the Legislature and ridiculing the latest scandals and ineptitudes of the current governors, who, with the exception of the inscrutable Dolph Briscoe, were good enough sports to attend regularly.

This year it was Pryor’s turn on the spit. The event was held at the new Special Events Center of the University of Texas, a massive coliseum encircled by access ramps that look like the rings of Saturn. It was filled with movers and shakers, women in extravagant gowns and men in tuxedos who had allowed their gray hair to fluff out over the ears in the current fashion of power. Women wearing sashes that read GIN or VODKA stood around with trays in their hands serving the audience, each member of which had paid $30 to see an assemblage of power-seekers and celebrities make jokes about Cactus Pryor’s toupee. John Connally was there, and Walter Cronkite, Dan Rather, Jack Valenti, Darrell Royal, and Erma Bombeck, along with several football stars and a sampling of dough-faced former governors of Texas.

“Tall and tan and lean and handsome,” Lee Meriwether sang to the tune of “The Girl from Ipanema,”

“The man called Cactus Pryor goes dancing,

And when he passes,

Each girl he passes goes . . . Yecch!”

Dan Rather conducted a mock interview with John Connally, a moment of strange-bedfellowism that was absorbed into the prevailing hysteria.

When his turn came, Pryor fended the barbs with finesse. “Jack Valenti, how fortunate President Johnson was to have your counsel. ‘Pick the dog up by the ears, Mr. President.’ ‘Show them your scar, Mr. President.’ ”

At the end of the show, just before the principals locked arms and sang a tribute to Pryor to the tune of “Hello, Dolly,” Lady Bird Johnson came onstage to announce that the Headliners Club had planted a cactus patch in Pryor’s honor at Town Lake.

Pryor had worked at KTBC, the Johnson family radio and TV station, for 33 years, and he was obviously touched by this tribute from his employer. The crowd warmly applauded Mrs. Johnson. Pryor’s roast was, in a way, a valedictory to an era that they had been seeing out for a long time. The stage was filled with the minions and protégés and offhand creations of Lyndon Johnson, and the closing moments of the show were strangely somber, as if the whole thing had been a kind of séance meant to invoke the spirit of LBJ.

Pryor never belonged to the deep inner circle of policymaking and busywork of the Johnson presidency. He was hired help, what studio personnel call, almost derisively, “talent.” He was Johnson’s funnyman. Perhaps it was that distance, and the attendant perspective, that made him seem the most durable and resilient character present that night. Watching him, I was impressed less by his sense of humor than by his sense of dignity and decorum, even embarrassment.

“I’m a little giddy right now,” he told me when it was over. “But I’ll be back down to earth Monday night when I speak to the Aransas Pass Chamber of Commerce.”

Pryor draped his Danish uniform jacket over the front seat of his car and then sat there with the motor idling, watching the audience file out of the Knights of Columbus Hall.

“This was a typical country audience,” he said, unwrapping a grape sucker. “These are the kind of people you get at chamber of commerce and co-op meetings. You’ll usually have barbecue for dinner if the population of the town is less than five thousand. If it’s a big city and in a hotel, it’s going to be steak, it’s going to be green beans, it’s going to be baked potatoes. There’s going to be Italian dressing on the salad. If it’s a chamber of commerce meeting in the fifteen-to-twenty-thousand population range it’s going to be a buffet, and on the buffet they’ll offer roast beef, chicken, and, if it’s south of Austin, shrimp.”

He had a few stories about his adventures as General Christoffersen that he proceeded to relate in a slow, thoughtful manner. Once, in Madisonville, he had let out that he was the quartermaster of the Danish Royal Air Force and had come to Texas to buy beef. The local judge adjourned his court and took Pryor out to inspect his brahman herd.

“I bought his whole herd of brahmans for five times the going rate. Bought two quarter horses too. Even negotiated for a hound dog that belonged to his boy. And then that night at the banquet I told the whole story. I tell you, I didn’t go back to Madisonville for five years. That judge was really pissed off.

“Another time I was the Danish Minister of Air, of which there is none. I was flown into Goodfellow Air Force Base, put up at the distinguished visitors’ quarters, shown all sorts of classified documents. I was wearing my high school swimming medals and an Interstate Theatres usher’s button.”

Pryor leaned back in his seat and held the wheel loosely. In the glow from the instrument panel he looked serene. He ran a comb through his fake hair, took the sucker out of his mouth, and more or less told me his life story.

“Dad was an old song-and-dance man,” he said, “but he misused his voice over the years—they didn’t have PA systems back then—so he spoke with just a rasp.”

When he retired from vaudeville, Skinny Pryor ran a movie theater on Congress Avenue called the Cactus. The name Cactus attached itself temporarily to a younger brother, Arthur, before it settled permanently on his sibling, who until that time had been known as Richard.

“My first memory is of that theater,” Pryor said. “I grew up in the front row. My mother was the cashier and my Uncle Wallace was the projectionist. Whenever the film would break or catch on fire and the kids started complaining, Uncle Wallace would yell out from the projection room, ‘Shut your goddamn mouths! I’m tryin’ to fix the goddamn thing!’

“What was unique about Dad’s theater was that Dad would get out in front and hawk the show in. He’d stand out there wearing his derby hat, firing a cap pistol in the air. ‘Cowboys shootin’ ’em up tonight! Sit too close to the screen and you’ll get powder bum!’

“Dad loved children like no man I’ve ever known. All you had to do if you didn’t have the price of admission was stand around and look hungry for a while. He’d send you on some little errand; that way he could justify letting you in for free. Once he caught two kids sneaking in and he showed them how to do it right. The trick was to get into the crowd that was leaving the theater and then walk backwards. He was actually in competition with his own box office at times.”

The adolescent Cactus wanted to be an opera singer and achieved some notoriety in junior high with his impersonations of Grace Moore singing “Funiculi, Funicula.” He was even scheduled to perform this act on the old Major Bowes Amateur Hour in New York, but two weeks before the event his voice changed, leaving him with the deep, down-home speaking voice that one suspects is a large part of his success.

During high school he supported himself by singing for a funeral home, performing freelance renditions of “Abide with Me” and “In the Garden” over the graves of the departed. He spent World War II as an emcee in the army, having washed out as an aviation cadet after one year because of “poor muscular balance of the eyes.”

After he got out of the service, Pryor attended UT and worked for several years at KTBC, the Austin radio station that had recently been acquired by the Johnson family. As a disc jockey he drew attention to himself by breaking records he didn’t like while on the air and ad-libbing commercials when his alcoholic copywriter left him with a blank continuity book.

In 1948, after a few years with South Texas radio stations, Pryor and his wife, Jewell, who was pregnant with the first of their four children, returned to Austin. He was rehired by KTBC and began to establish himself as a media presence, first in radio, then in television, in his hometown. He would broadcast from his house, interviewing his own children as they grew up. In the early fifties he did a series of successful parodies of popular records—“Jackass Caravan,” for instance, which was a takeoff on “Mule Train”—and scored with a satire on the Army-McCarthy hearings called “Point of Order.”

At KTBC he could hardly have been in a better position during the Johnson years. The national fame he had been only half-heartedly courting eventually came to him. As the official humorist and emcee for the Johnson presidency, he was in charge of entertainment for those legendary barbecues on the LBJ Ranch at which various foreign dignitaries sat dumbstruck watching coed bullwhip artists, Texas Ranger target shooters, and a monkey dressed as a cowboy tied to a collie herding sheep. The Eastern press called Pryor the “Georgie Jessel of the campfire circuit.” He met John Wayne and took bit parts in The Green Berets and Hellfighters, appeared on The Merv Griffin Show, received standing offers from famous comedians to sponsor him in New York. Ultimately, none of it came to much.

“I don’t think I’m tough enough to exist in that game. God, you’ve got to be tough and single-minded in your purpose. It’s one of the great ambivalences of my life—my lifelong romance with Austin and the desire to do something like, say, The Tonight Show. The two are irreconcilable.”

One can sense a strange, compelling, and perfectly respectable lassitude in Pryor’s personality. It would not be accurate to say he has no drive, but there is a definite lack of the nervous energy that might have helped boost him to the top. He comes across as languid, absorbed in some continuous reverie about the Cactus Theater, about the old days in Austin when he would watch his father floating sound asleep on his back in Barton Springs. In his case this is more than nostalgia, it’s a kind of addiction. Pryor is metabolically tied to the rhythms of his birthplace, and perhaps one reason for the cautious course of his career is a suspicion that those rhythms will not travel.

The LBJ experience, nevertheless, seems to have charged him.

“I’ll never forget the feeling of knowing that today I’d be speaking to the Smithville Chamber of Commerce and tomorrow I’d be speaking to the ambassadors at the United Nations. I miss those years because they were so heady, but they were also very scary. I almost dreaded to get the call from the White House.

“I think it was Newsweek that said I was the only man who could kid Johnson and get away with it, but I made him mad on occasion. I remember one time we had a Christmas party for the staff of the station. This must have been when he was running for the nomination against Kennedy. I’d gotten hold of a Face the Nation tape he’d just done and substituted my own gag questions and spliced in his answers. The effect was pretty funny. Well, he arrived in a foul humor to begin with. Ronnie Dugger had written a story in The Texas Observer about him that he was displeased with, and he had bent the fender of his brand-new Lincoln on the way to the station. He stood up at the back of the room while we showed the film. There were gales of laughter at first, but gradually it started to quiet down and I realized what was happening. He was displeased and it was catching.

“I found out later he chewed out everyone who had anything to do with the party, but he never said a word to me. His attitude toward me after that was like that of a little boy whose feelings I had hurt. I wanted to walk up to him and put my arms around him and say, ‘Look, I did what I did because I like you.’ But of course I couldn’t. We didn’t have that kind of relationship.”

Even after the evidence of the roast, it was hard for me to imagine Cactus Pryor with any real access in the world he was describing. Though he was instrumental in hiring the first black DJ in Houston in 1948 and stood by his friend John Henry Faulk during his battle with the blacklist, he is the sort of person who is constitutionally apolitical, whose immediate human sympathies divert him from larger and more abstract causes. He is loyal to his vision of Austin as an earthly paradise, to the LBJ legacy, to Mrs. Johnson, whom he admires unreservedly. He is, as one of his Austin colleagues describes him, “a company man all the way.”

But to most political heavies in Texas, Cactus Pryor has revealed himself at one time or another as the rat in the woodpile. His wit is never vindictive, but it can be very pointed and immediate.

“I remember when ol’ Preston Smith got into difficulty on that Sharpstown bank stock thing,” John Henry Faulk told me. “He was to be the guest of honor at the Headliners show a couple days later. So Preston calls up Cactus and says, ‘I know you’re going to take me apart at this thing, but could I come up and see you first.’ Well, Cactus says, ‘Governor, I know you’re a busy man, tell you what, I’ll come down and see you.’ So Cactus goes down to the governor’s office, and Preston says, ‘I know you’re going to rake me over the coals, but could you write me some answers.’

“Well, this wasn’t anything new. Hell, Cactus writes the replies for all those turdknockers. So Cactus comes over to my house and says, ‘Bless my heart, let’s write Preston a speech.’ So we write this thing. Of course, every one of them had sucked eggs and robbed the henhouse, it’s not just ol’ Preston boy. So we had him come out there and put a rock down on the podium and say, ‘Let he who is without stock cast the first rock.’ Hell, it brought down the house!”

I dropped into the KTBC television studio a few days after the Sealy banquet to watch Pryor work. (The Johnsons sold their interest in the TV station in 1973, retaining the radio station and redesignating it KLBJ.) He does an interview show called Noon, one of those “public service” stopgaps featuring charity doyennes, fashion previews, and scenes from local theater productions of Stop the World—I Want to Get Off. About a year ago, out of pure torpor, I had fallen into the habit of watching this show. Pryor’s cohost at that time was Donna Axum, a former Miss America once married to a Speaker of the Texas House, Gus Mutscher. She was very sincere and never failed in her duty to her guests—“Now tell our audience exactly when and where the bake sale will take place.” Meanwhile Pryor would sit back in his chair, drumming his fingers on his knee, trying to catch a fly in his hand, occasionally interrupting a chatty conversation about home insulation or hem lengths by cracking an awful joke.

Miss America published a spiritual autobiography and moved on to another market. Her replacement, Barbara Miller, is a rare find, an intelligent and intense woman so telegenic she might have cathode-ray tubes for arteries. She and Pryor have a video marriage made in heaven, and their on-camera banter and rapport soon accomplished the not terribly difficult task of obscuring their guests and began to hint at the inanity of the format in which they were trapped. It struck me as the subtlest form of guerrilla television possible.

The day I visited the studio, Pryor did not come down from his office until ten minutes before the live show was to begin. Miller, who also produces the program, introduced him to a Pentecostal minister who was plugging an international evangelism conference, along with his wife’s record, a collection of inspirational songs that Pryor inspected soberly.

“I do not know until he opens his mouth what Cactus is going to say,” Miller told me. “Spontaneity is everything with him. I shift myself into neutral, then go to first, second, third, or overdrive depending on what he does.”

“Happy Friday the Thirteenth,” Pryor said into the camera when the show began. He turned to Miller. “Do you suffer from triskaidekaphobia?”

“As a matter of fact, yes.”

“Did you know that the last time Friday the Thirteenth occurred on a Good Friday was in 1872? In Evansville, Illinois, as a matter of fact.”

“Read the weather, Cactus.”

“The weather today is going to be exactly what it was on Friday, April 13, 1872, in Evansville, Illinois.”

And so on. They talked to the minister awhile. Pryor’s awareness seemed to ebb.

“Now you’re going to introduce Wanda Phillips,” Miller said to him on camera, in a tone of voice that a nursing home attendant might use to rouse a patient.

Pryor seemed slowly to inhabit his body. He looked into the camera. “Here’s Wanda Phillips,” he said.

Wanda Phillips sat on a stool at the other end of the studio, lifted her eyes to heaven, and sang a song from her album.

In the studio one could not hear her voice, only the faraway sound of a prerecorded soundtrack.

During a break a woman dressed as the Easter Bunny, wearing a terry-cloth suit, tennis shoes, and a bunny tail hanging by a piece of electrician’s tape, ran into the studio. “I don’t even know what I’m supposed to sing,” she said frantically.

It was decided she would not sing, since time was running short, but would just sit on Pryor’s lap and announce the upcoming Easter egg hunt at Symphony Square. Pryor accepted this without complaint, and when he was back on the air he stared soberly into the camera and said, “Uh, you might have noticed that I have an Easter Bunny sitting on my lap . . .”

After the show, we went to eat barbecue, and Pryor told me about his latest obsession, competing Labrador retrievers in an arcane sport known as field trials. “It’s just like the golf circuit,” he said, “only very esoteric, very sophisticated. And when you win there ain’t no way you can tell anybody what you’ve accomplished. Nobody gives a damn.”

That afternoon I went with Pryor to pick up his dogs at the Canine Hilton, a kennel he owns with his high school friend John Ramsey.

The Canine Hilton is a “pampered pet” center whose facilities have names like the “Jet Set Suite,” “Pet Carin’ Island,” and the “Neiman-Barkus Gift Shop.”

“Our approach is anthropomorphic,” Pryor explained.

Pryor changed into a white jumpsuit and a Canine Hilton gimme cap. He and Ramsey got their dogs out of the kennel. There was one yellow Labrador and three others that were black and sleek as panthers. The dogs hopped eagerly into their individual compartments in a custom-made dog trailer that resembled a giant refrigerated pastry cart. We hooked the trailer up to Ramsey’s motor home and drove about a quarter mile to a little lake on the manicured grounds of a sewage treatment plant that had been cleverly disguised to look like a country club.

“What do you think about this for a bank-running test?” Pryor asked Ramsey, indicating a part of the lakeshore where a blunt peninsula extended into the water.

A field trial is something like a war game, a controlled assessment of a hunting situation, with emphasis on the dog’s obedience to its master’s signals. In a competitive trial the dogs retrieve freshly killed game birds, but in practice Pryor and Ramsey used plastic boat bumpers, which they set out on the far side of the lake while the dogs were still in their trailer.

“The inclination here,’’ Pryor told me, pointing to the peninsula,‘‘is for the dog to run on land. We want them to go from land to the water, up onto that point, and back into the water to land again. It’s typical of the tests run in a field trial.’’

He unloaded the yellow dog and sent it off. It jumped into the water and did more or less what it was supposed to do.

“That’s a pretty good line,’’ Pryor said. ‘‘He pretty well knows by now he has to go over those points. He and I are the same age.”

The other dogs were younger and tended to stray off the route Pryor had imagined for them. At such times he would blow his whistle, and the dog would crouch, look back at Pryor, and alter its course in accordance with his gestures.

It was a strange, intriguing sport—the guiding by force of will of a far-flung ally. Pryor was respectful of the dogs, though once or twice he walked up to them and yanked their ears in a manner that reminded me of his former boss. He was absorbed; sending the dogs on their errands seemed to settle some turbulence inside him.

‘‘The appeal of it,’’ he said, “is functioning as a team in concert with your animal. I’m much more nervous when I go to the line with my dog than when I’m speaking to ten thousand people. Much more nervous. Because you’re not in control. I know this surgeon—a fantastic surgeon. I’ve seen him go to the line with his hands shaking.”

One of the dogs came back from the lake, carrying the bumper in his teeth. Pryor took it out of the dog’s mouth and threw it out at random, letting the animal make his own course to it.

When it began to get dark Ramsey went out to retrieve the rest of the bumpers. Pryor ushered his dog into the trailer.

“I’ve kind of always made fun of hobbyists,’’ he said, ‘‘and here I am. But shit, it’s survival. I’ve almost bled to death four times from hemorrhaging ulcers. I’ve had two cancer operations in the last five years. After the second one I was out here training dogs the day I was out of the hospital. Against doctor’s orders.”

The operations had both been removals of melanomas, and both were successful. ‘‘But every three months,” Pryor said, ‘‘you go back to be checked and you die a little bit.”

Gilbert Peake, the science editor of the London Times, strolled through the lobby of the Loews Anatole Hotel in Dallas on his way to address a group known as the On-Line Software Builders. The hotel, with its massive skylit interior, its kiosks and shops and soaring glass elevators, looked like an artist’s conception of a space colony, a self-supporting remnant of Dallas couture hurtling through the void.

As Gilbert Peake, Cactus Pryor was wearing rimless glasses, a pinstripe suit, and a little splash of sangfroid.

“Do you have Dubonnet?’’ he asked the bartender. ‘‘No? Well, you have Perrier water, I hope? With a twist of lime, please.”

The software builders were young, aggressive, and on the make. They flocked around Pryor, who was unflappable in their presence, engaging them in technical conversations about computer language, inviting them all to London (“Of course the Times retains a marvelous chef for us. Please don’t hesitate to call’’), and prevailing upon them to procure girls for him.

“You understand my interest is academic rather than physical.’’

“Oh, sure.”

He milled about, audaciously pinning his listeners to the wall, keeping on the offensive. He was introduced to a woman whose last name was Milsap.

“A very English name,’’ he said.

‘‘Really? I didn’t know that.”

“Oh, yes, it’s a very common name. Originally, you see, the name was Middlesap. It referred to a person of not very high intelligence who was hired to frighten the nesting birds away from granaries. A human scarecrow, really.”

“Oh.”

Before dinner Pryor retired to a rattan chair in the lobby to make notes. After a while some big doors were opened into an auditorium, where a lavish buffet had been set. There was an ice sculpture, and a turkey carcass festooned with glazed fruit, and desserts shaped like swans.

Peake and I were seated at a table near the podium. There were half a dozen other people at the same table, including a man who had an inexhaustible repertoire of desperate jokes that reached a nadir during a discussion, initiated by the lascivious Gilbert Peake, of boob jobs.

“If Computer Data Systems uses up all the silicone, the whole industry could go bust,’’ the man said. ‘‘Bust, see?’’

“This is the original lampshade-on-the-head guy,’’ Pryor whispered to me. As Gilbert Peake he merely raised an eyebrow. He listened to the talk about Cullen Davis, about the price of Valium, and grew restless. It was clear he was not on his preferred ground, among the solid beef-fed citizens of Sealy, Texas. He adopted a kamikaze style.

“I’m to go to Austin tomorrow to be interviewed by a person named Cactus Pryor,” he said. “I hesitate to be interviewed by one with such a name.”

Not a nibble. The conversation turned to Lyndon Johnson.

“Oh, I just loved LBJ,” a woman next to me said. “I loved that man. When I lived in Austin I toured the LBJ Library every week.”

Another woman on the opposite side of the table perked up. She was very tanned, with one of those elaborate upswept hairstyles and a loose bracelet that slid to her elbow when she put her hand thoughtfully to her chin.

“What would you say,” she asked, “if you found out that LBJ had Kennedy killed?”

The other woman looked at her, puzzled.

“Oh, I have no evidence, of course. I just feel that way. I guess it’s because I’m a Texan and I was always embarrassed by the way Johnson talked.”

Pryor nibbled at his dessert, struggling to remain in character. On his wrist, in plain sight, was a watchband decorated with the presidential seal that Lady Bird Johnson had given him for emceeing a national tribute to her.

The strain of my own artifice was beginning to get to me, and I looked down at my plate and lapsed into the role of silent observer. Pryor, of course, had no such option. He had to get up and deliver a speech, to be funny as a visiting Englishman and then to be even funnier as himself. He was introduced as a former Spitfire pilot, a two-term member of the House of Commons, the father of three sets of twins. He pulled it off, and when the audience saw themselves exposed they laughed in a sophisticated, knowing way.

“That was the best thing I’ve ever heard in my life, period,” a young man told Pryor. He accepted the compliment graciously.

“God, that’s work,” he said back in his hotel room a few minutes later. “Those cocktail hours are work! I was earning my keep tonight.”

It was not over yet. His audience was expecting him for another hour or so of small talk.

“The conversations afterward are always the same. You go to a reception and they still expect you to be an entertainer. That’s the hardest part of the show. After.”

He sank farther into his chair. He looked exhausted and saddened, as if some price had been exacted from him for a lifetime of horseplay. He brightened when he thought about where he was going in the morning: to Oklahoma to compete with his dogs.

I walked him to the elevator, wished him luck in the field trial, and then watched as he was borne soundlessly aloft to the hospitality suite.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- LBJ

- Austin