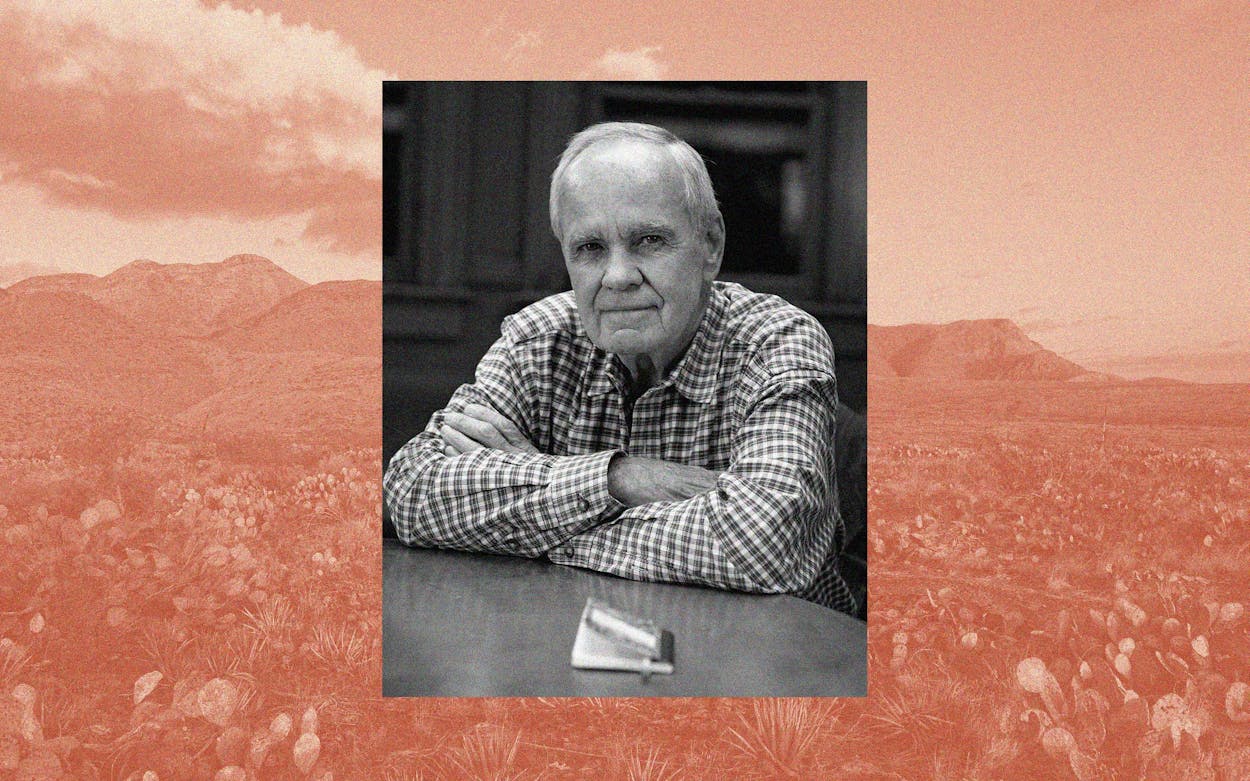

Cormac McCarthy, who died Tuesday at 89, was a giant of American literature. The author began his literary life writing stories set in southern Appalachia—McCarthy, born in Rhode Island, grew up and received his education in Tennessee—but he would write his greatest works in the years after his 1976 move to El Paso, where he lived for roughly two decades before settling in New Mexico. El Paso and the Southwestern borderlands would inspire such timeless novels as 1985’s Blood Meridian; the Border Trilogy, which included the 1992 National Book Award–winning novel All the Pretty Horses; 2005’s No Country For Old Men, of which the Coen brothers’ film adaptation won four Oscars, including for Best Picture; and 2006’s The Road.

Below, some of Texas’s best writers reflect on McCarthy’s stories, his literary legacy, and some of the mysteries he left behind.

Growing up as a writer in the nineties and aughts, McCarthy was a godlike figure. He seemed to fashion sentences out of primordial clay. You figured if you drove far enough west in Texas to where the setting sun scorched the land black, you might find him, a wisp of smoke rising from a lonesome jacal. I don’t think kids today read him as much. They should. His blood-soaked telling of how the West was won in Blood Meridian is more nightmarish than anything you’ll find in critical studies. To the end, he was finding new registers that others will surely imitate, as so many have lately ripped off The Road with lesser, more sentimental dystopias. His final pair of linked novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, are another gorgeously dark vision we’ll be unpacking for years. Rarely has the veil between this world and the unknown felt so thin as when I set it down. —Michael Agresta

Cormac McCarthy helped me appreciate the beauty, conciseness, and bone-dry humor of a Texas where the feedstore and the local Dairy Queen are the big draws in town. A prime example is a succinct comment from my favorite of his novels, All the Pretty Horses. Lacey Rawlins orders eggs in a diner and peppers them until they’re black. The owner observes laconically, “There’s a man likes eggs with his pepper.”

I didn’t fully appreciate just how right McCarthy got his dialogue until I was researching my novel Virgin of the Rodeo, a process that involved a lot of eavesdropping in those local DQs. And that is where I heard one old-timer look up from his dominoes and his ninth coffee refill to behold his buddy crop-dusting a plate of eggs with pepper. “Like a little egg with your pepper?” he quipped.

From the accretion of perfect details like that, McCarthy built a godless, glorious universe that was utterly believable and utterly transporting.

Sometimes there’s a writer so singular, so pervasive, who captures a certain poetry from the region where you live so distinctly, that, if you’re also writer, you just have to pretend this other person doesn’t exist.

More than anything, McCarthy’s work captures the mentalities of the men who have caused havoc throughout the Southwest and who continue to cause havoc here. The riders of destruction no longer gallop from town to town scalping innocent people, leaving a river of blood in their wake, but wear suits and ties, with fancy college diplomas hanging in their offices, and prefer their barbarities to be kept out of sight. There is nothing polite about McCarthy’s depiction of the South, the border, and these places’ inhabitants.

I’m reminded also of McCarthy fans throughout the years who scorned Spanish text in works by Mexican American and Latino writers, but when it came to McCarthy, they called it art—but that’s for another day.

As a scholar of the West, I’ve long been drawn to McCarthy’s books about the region. What I admired most was how, with his early novels like Blood Meridian, he was peeling back the layers of myth even before the emergence of revisionist Western history in the late 1980s and early 1990s. But it’s one of his last two books, The Passenger, that might be my favorite, partly because of the same extraordinary sense of place he conjures (this time with the Gulf Coast), but especially for his stark refusal to tie up any of the story’s loose ends. Though apparently he’d been working on the book since the 1970s, its murkiness and disquiet seem perfectly suited to the present moment.

I used to be a Cormac McCarthy fanatic, part of the cult of readers, academics, and weirdos who parsed his sentences and memorized his paragraphs and drove slowly past his house on Coffin Avenue in El Paso and went through his garbage. For me it began when a friend basically forced All the Pretty Horses on me thirty years ago, stuttering and struggling to convey the dark beauty of the book—and then, after I finished, I did the same thing to someone else. “Read this,” I implored. It wasn’t just McCarthy’s words or his naked, almost biblical cadences, I wrote in this magazine. “It was the vision of another world—our world—and the possibilities that lay in crossing over into it with eyes wide open and the terrible, impossible price to be paid for following your heart.”

I don’t go back and reread McCarthy much, though I’ll watch the film version of No Country for Old Men every time it pops up on cable. The Coen brothers somehow improved on the book—by eliding McCarthy’s bizarre faux pas in the very first sentence (Texas never used a gas chamber to execute anyone) and making a grim, funny, horrifying story grimmer, funnier, and even more horrifying. McCarthy’s friend Bill Wittliff once said about him, “He makes you feel, which is an awesome gift.” Tommy Lee Jones, playing sheriff Ed Tom Bell, somehow makes you feel even more.

The beauty of reading any of McCarthy’s works is that there is absolutely no one in the world besides him who could have written them. To his own detriment, I guess. Playing golf seems like more fun. McCarthy’s books are personal, and intimate, and brutal books. I return to them often, not for their plots or for the strange punctuation everyone is obsessed with, but because McCarthy never holds a punch. He gives it all, immediately, every single time. Or, I guess now I should say, he used to. It is tragic whenever any great Texas writer dies, because it is the end of the canon. But the loss of McCarthy feels like a bit more. McCarthy was one of the few American writers left who truly did not give a damn about the market, or the money, or the glory, and his work shone because of it.

In the nineties I read All the Pretty Horses and marveled at the mystic beauty of the horse as metaphor for the infantile joy that Freudian psychology describes. Of the book’s title, I only thought about one word: “horses.” I admired how McCarthy squared his work’s macho-guy violence with all that equine peacefulness.

Later I learned the title’s origin. It’s from a lullaby sung by enslaved women to infants. Listen to this version by Odetta. It starts with all the pretty little horses. It progresses to bees and butterflies pecking at the eyes of a lamb—perhaps symbolizing babies injured while their enslaved mothers were away doing forced work?

Did McCarthy know this song’s origins or understand them? His work is so Southern, so white. These questions haunt me.

No one wrote like Cormac McCarthy, but it sure was fun to try. His authorial voice was marked by a handful of stylistic markers—terse, often fragmented sentences, at least until he found a run-on that he liked so much he let it run and run until it was longer than the combined length of the three or four sentences that preceded it; a disdain for quotation marks and apostrophes; language simple in its structure and ornate in its vocabulary. Imitating McCarthy became a game of sorts—impostors popped up on social media, fooling the credulous, as though the author, who said in 2009 that “my perfect day is sitting in a room with some blank paper. . . . That’s gold and anything else is just a waste of time,” would bother with Twitter—but the real winners were those who learned that a writer is more than just a collection of literary tics and personal conventions. The ease with which one could imitate McCarthy’s prose style never brought anyone who tried closer to his insight, his gift for storytelling, or his ability to make the mundane feel impossibly vibrant. There’s a lesson in that for all of us.

As an aspiring writer growing up in rural West Texas in the eighties and nineties, my friends were as likely to be in weekend garage bands as to be riding horses. Cormac McCarthy showed us that you could write about places like where I came from—the vastness and violence, the sweetness and off-the-wall weirdness—without giving up the genre of the western. He taught us that you can make it your own. That anything is possible, nothing off-limits. “It’s a mess, ain’t it, Sheriff? If it ain’t, it’ll have to do till one gets here.”

I read and enjoyed Cormac McCarthy’s early work when I discovered him as a young writer—The Orchard Keeper, Suttree, and especially Blood Meridian. He was a master stylist and understood that shedding blood and fighting life-and-death struggles were the stuff of great literature. Later in life, I kept reading the more popular Border Trilogy (All The Pretty Horses, The Crossing, and Cities of the Plain), and although I liked these books about the Southwest, they didn’t strike me as powerfully as The Road and No Country for Old Men. The biblical and apocalyptic themes set McCarthy apart from many contemporary writers, and his well-honed style often seemed chiseled onto the page, but Mexicans and Mexican Americans weren’t depicted as real characters in his works: they were more like props. So I took what I could from him as a writer, especially his style and certain themes about outsiders and loners in a country with collapsing myths. I admired him for his fierce independence.

I read All The Pretty Horses, my first Cormac McCarthy novel, while camped at the base of the Guadalupe Mountains. I remember the day vividly, not because we’d hiked to the tallest peak in Texas, but because never before had I seen language arranged with such purpose and precision and unadulterated beauty. It was, without hyperbole, a religious experience. I read the book cover-to-cover in one sitting. When I finally stood up, I was a washed-in-the-words zealot of Cormac McCarthy.

I read his entire catalog by the end of the year, then went back and started again. I tried to learn all I could from his novels and from critical analysis written by McCarthy scholars.

He broke so many conventional rules of writing, which I thought was just wonderful. As an aspiring author, he gave me an excuse to experiment with style. Gave me permission to take on metaphysics and philosophy in my work. And above all, he gave me endless inspiration to improve my craft.

The way he moved effortlessly from Southern Gothic to Western to Post-Apocalyptic landscapes without losing a drop of his singular style is a testament to his skill as a storyteller. In my estimation, he is peerless. Through McCarthy’s elegant prose, mastery of naturalism, and unflinching look at human nature, we have been shown the highest of possible heights for the American novel.

— James Wade

- More About:

- Books

- Writer

- Obituaries

- Cormac McCarthy