Stories in this article are featured in episode five of our podcast America’s Girls. You can dive deeper into the stories from the show in our Pocket collection.

Subscribe

“Dana Presley was one of the first cheerleaders I actually knew,” the legendary and recently retired sports reporter Dale Hansen told me, as I sat across from him in the Waxahachie home he shares with his wife Chris. I hadn’t asked Dale a question yet, but that didn’t stop him. He was traveling back in time to the early eighties, when he first arrived in the land of superhighways and reflective glass to work at the local TV station WFAA after a childhood in Nebraska. He threw a big bash each summer, and he’ll never forget the day a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader named Dana Presley walked in, wearing heels and a tight white skirt. There was a dance contest, and it was Dana’s turn.

“She was able to do things on a dance floor that I just didn’t think the human body could do,” he said, in a voice so expansive I was still fiddling with the microphone levels. “And about the third chord of the song I said, ‘We have a winner, ladies and gentlemen. The contest is over.’”

Dana Presley didn’t actually have much dance training when she joined the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders in 1981, but she did have a special something, and men seemed to notice. She grew up south of Fort Worth in a town called Burleson, home of Kelly Clarkson (but not yet), and she studied radio-television broadcasting at the University of North Texas, though she didn’t graduate. She got married in college to a popular Elvis impersonator. She was twenty years old when they were watching a Cowboys game and she mentioned she might like to try out. “You’ll never make it,” he told her, and that was all the incentive Dana needed. That guy turned out to be not very nice, and the marriage wouldn’t last long. But he had a point. By 1981, the cheerleaders were riding a pop-culture high that brought more than 2,000 women to Texas Stadium each spring to vie for a mere 36 spots.

Director Suzanne Mitchell and choreographer Texie Waterman were not so impressed with Dana, but a local photographer acting as one of the judges secured her spot. At the time, each judge had a “trump card” vote they could use on one candidate, and that guy thought Dana had an Angie Dickinson quality, at least that’s what he told her later. With her shoulder-length blond hair and a body that didn’t quit, Dana certainly had the look the cheerleaders made famous. And she did struggle with the dancing at first. You can get a sense of internal cheerleader hierarchy by looking at squad photos, where women in the front are generally considered more prominent. “The blonde on the back row” is how Dana referred to herself back then.

But Dana had plenty of other talents. She could sing, and often closed out the USO shows with a rousing rendition of Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA,” which she performed as a duet with another cheerleader (sometimes with Demi Lovato’s mom, Dianna de la Garza). And boy could she talk. “What’s the saying?” she said, as she made lunch for us not long after a winter storm that walloped the state. “I was vaccinated with a phonograph needle.”

I was seated on a stool in the kitchen of the lovely East Texas home she shares with her second (much better) husband. I was eating a cookie, being relatively useless, as Dana swiveled from refrigerator to cabinet making us roast beef sandwiches. She regaled me with stories from the telethons that were staples of the cheerleaders appearances during the eighties, halting only occasionally to offer rye, sourdough, or wheat, and then mayo, mustard, or horseradish. (The sandwich was delicious.)

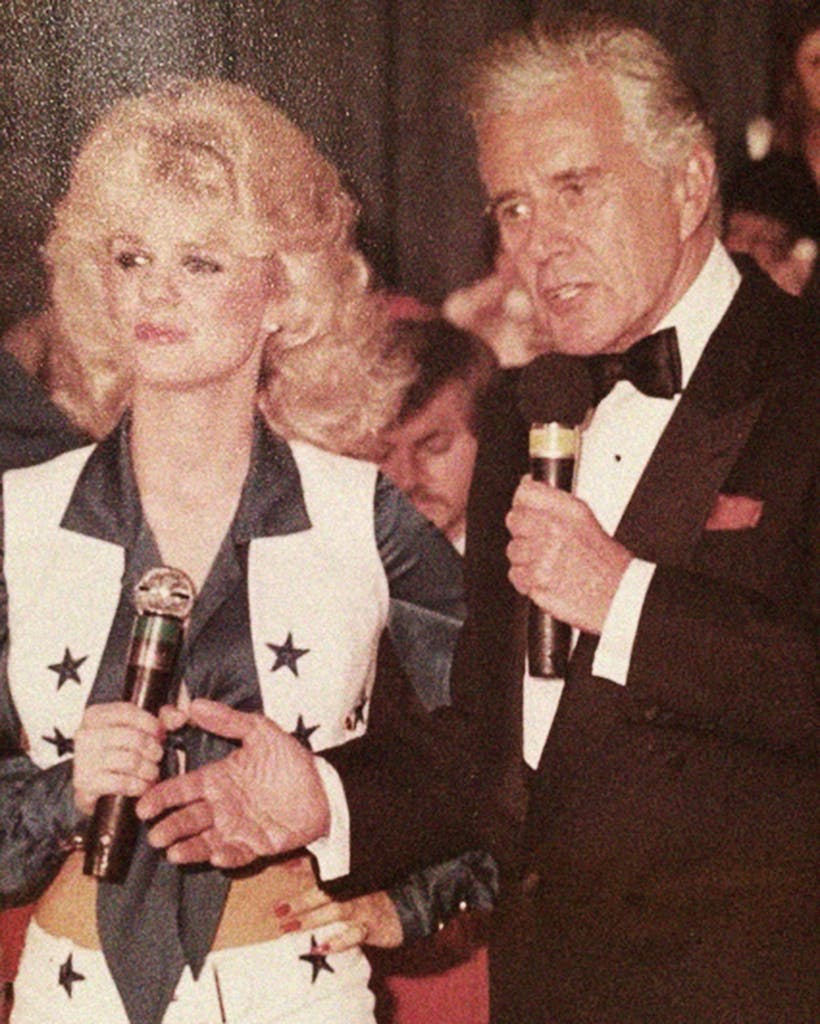

She told me about a Variety Club International telethon in Chicago where Kathie Lee was supposed to cohost. She wasn’t Kathie Lee Gifford yet. In fact, Kathie Lee had pulled out of hosting because her then-secret relationship with then-married sports commentator Frank Gifford had just hit the tabloids. So Dana filled in, joining a roster of celebrities that included Dynasty actor John Forsythe, David Hasselhoff, and Sammy Davis Jr.

Dana was good on her feet. The trick at telethons, she explained, was that you had to keep talking, and that was no problem. “I said cornpone things. ‘Get up and walk for the kids who can’t walk.’” At one point, she threw out a quip that lit up the phones. “Get off your lazy”—and here she paused for effect—“boy recliner and make that call.”

“That’s good!” I said, with a mouthful of cookie.

In fact, Dana reminded me a bit of Dale Hansen, who eventually became a friend. They each had charm to burn, and a steel-trap memory for dates and details that made them excellent storytellers. Dana was once offered a gig as a TV anchor in St. Louis, but she was remarried by then, and her husband had two children from a previous marriage that she adored. She chose family over that path, and she never regretted it. She had a pretty bang-up career anyway.

“I’ve been a CEO of a $30 million consumer goods company. And right now I’m executive vice president of sales for a $35 million manufacturing company out of Chicago,” she said. “But the minute someone hears I was a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader, that’s what they want to hear about. It’s weird to me, but it’s been going on for more than thirty years now, so I’m used to it.”

And those four years on the squad were action-packed. USO tours to Korea, the Philippines, some place called Diego Garcia. Telethon after telethon. A 1982 workout album called In Training With the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, where Dana appears on the cover with nine other women. (She signed my copy.)

Then there was the unfortunate run-in with feminists at Fresno State University, where a female professor organized a protest against the cheerleaders’ half-time show. They got off their bus that afternoon to find a sign the size of a bedsheet that read, “Hearts and minds, not bumps and grinds.” (Dana tells these stories in episode five.)

Dana never really understood the backlash. “There was no changing their minds that we weren’t being manipulated or objectified, but we really were doing what we wanted to do. No one forced me to be a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader.”

The word “exploitation” gets thrown around a lot with the cheerleaders. After all, they were paid only $15 a game. But can you really say a person is being exploited if they tell you they aren’t? I’m a writer who has worked for free, during an online era when publications sometimes pay in the equivalent of postage stamps and ketchup (they call it “exposure”). During the past year, I’ve had many conversations with writer friends about the financial exploitation of the cheerleaders, and it has not been lost on me that at other points, we griped about publications that didn’t pay on time (or at all), expected us to promote ourselves on social media and research complicated story pitches with no promise of compensation. If someone told us we were being exploited, I doubt we could convince them otherwise. But I would point out that I also fought tooth and nail for this privilege. Dana would do the same.

One of the most fascinating parts of our three-hour interview concerned the issue of cheerleader pay. I was frustrated that (for various reasons relating to the narrative demands of a podcast) we couldn’t include my antic back-and-forth with Dana. Of course the cheerleaders knew they weren’t being compensated well, she told me, a fact of life they treated mostly with humor, shrugs, and a little behind-the-scenes griping.

“Suzanne valued us,” she said, meaning director Suzanne Mitchell. “But as far as the organization, they saw us as fluff. We were the entertainment, the sizzle, but we weren’t so important as to actually pay us for it.”

In 1980, a year before Dana joined the squad, some of the cheerleaders actually lobbied for a raise. The merchandising arm of the cheerleaders was at full tilt—calendars, playing cards, Frisbees—and a group of women, including Vonciel Baker’s sister Vanessa, approached Suzanne with a list of demands for general manager Tex Schramm. No luck. I saw the letter Suzanne wrote to the squad, breaking the news. “I hope with all my heart you will always be proud of being a part of something so very special. To me, the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders are like America herself. It’s not perfect, but it’s certainly the best this world’s got.”

Suzanne held firm to the bottom line. Being a cheerleader was an honor and a privilege, and if you didn’t like it, there were at least 1,964 women eager to take your spot. And being a cheerleader came with other rewards. A rare status, a taste of celebrity, the thrilling game-day experience.

But Dana launched her own protest once, though a very good-natured one. In her final year on the squad, she was appearing at the Family & Friends Show, an annual event where cheerleaders give solo performances for an invitation-only audience. Tex Schramm was there. She had permission from Suzanne for a little gentle ribbing. Dana was singing Donna Summer’s “She Works Hard for the Money.”

“And at the end, the song says, ‘so they better treat her right.’ And then you hear that click in the auditorium when the lights go down, and there’s a spotlight on Mr. Schramm. And I said, ‘Mr. Schramm, how about $15.50 a game?’”

The auditorium went dark. And everyone laughed, but nothing ever happened. In fact, the $15 pay rate stayed in place till the nineties. (The nineties!) That’s when it was bumped to $50, then it became $150 in the aughts, and somewhere after 2010, it went up to $200 and the cheerleaders started getting minimum wage for rehearsal time. But there was simply no incentive to boost the pay much more, when so many women were still vying for those coveted 36 positions. Don’t like it? There’s the door.

Then in 2014, a cheerleader named Lacy Thibodeaux, formerly of the Oakland Raiders, filed a class action suit against her team, launching a wave of lawsuits across the NFL. (The excellent 2021 PBS documentary A Woman’s Work covers this story.) Dana was at the NFL Cheerleaders Alumni Organization conference in 2014, shortly after the lawsuit hit, when this became a hot topic.

“The room was divided,” she said, as we sat in her living room next to a roaring fire. “There were five hundred women in the room who were former cheerleaders, as young as twenty-seven years old and as old as seventy, and some felt like the lawsuit was frivolous and it would get the cheerleader organizations kicked out. And others said it’s about time.”

The fear that lawsuits would bring an end to professional cheerleading as they knew it was not unfounded. When five former cheerleaders filed a class action suit against the Buffalo Jills, the team folded its squad. It just wasn’t worth the trouble. Squads in Seattle, Baltimore, and New Orleans (among other places) would rebrand and become coed teams, and the sexy sideline dancing that had been central to Dana’s formation was starting to look more like an endangered species. Still, she was one of those cheerleaders who thought it was time. Suzanne Mitchell, who accompanied her to that conference, was on the other side. She saw cheerleading as a labor of love, end of story.

Dana had become friends with Mitchell, who died of pancreatic cancer in 2016. Dana gave the eulogy at her memorial. (Lee Greenwood also sang, and I bet you can guess what song.) Although Mitchell had not wanted Dana on the cheerleaders back in 1981, Dana quickly won her over. They became close after Dana confided the horrible situation of her first marriage. (Dana talks more about this in the excellent 2018 documentary Daughters of the Sexual Revolution.)

Suzanne was known to take cheerleaders under her wing, and Dana was a bit of a wounded bird at the time. In 1985, Dana became Suzanne’s assistant for a short spell, and she saw another side of their fearless leader.

“She had terrible arthritis,” Dana said of Suzanne. “She was thirty-seven years old, and when it got really cold, sometimes her hands would cramp up and she walked with a cane.” Suzanne, who was arguably tougher than any man in the Cowboys organization, never showed weakness. “Other days she looked like this young, gorgeous model in her high-heeled black boots and her halter feather top and her cowboy hat walking around the game.”

So it’s surprising to me that Suzanne didn’t fight harder on the money front (though I have no idea what she actually did)—but the money never changed. Suzanne reframed cheerleading as a path to personal development. “A girl becomes a LADY,” reads one handout from the eighties. And some experiences really are beyond dollar value, and no doubt there are many things we all do regardless of compensation—but it bothers me that this altruistic enterprise was in the context of a massively profitable sports franchise. The cheerleaders were part of that profit. In the early eighties, Dana worked for Triland, a real estate investment firm that partnered with the Cowboys to build a vast football complex at Valley Ranch. As part of her job, Dana delivered a spiel. “In 1983, the Dallas Cowboy cheerleaders sold more merchandise than twenty-six of the other NFL franchises,” she told me. “We sold more merchandise than the entire Buffalo Bills franchise, the entire New York Jets franchise, just the cheerleaders.”

And that’s to say nothing of the enormous value they brought to the organization in terms of visibility, glamour, and goodwill. “One of the best marketing tools in the history of marketing,” said Dallas journalist Candy Evans, who wrote the 1982 history of the cheerleaders, A Decade of Dreams.

So maybe it should come as no surprise that in 2018, the Cowboys cheerleaders got hit by their own law suit. Erica Wilkins, a three-year veteran who appeared on the cover of the swimsuit calendar at one point, filed for back wages, eventually reaching a settlement with the Cowboys. (We talk more about this lawsuit in our upcoming final episode.)

“That one was weird,” Dana said, shaking her head. She could understand a cheerleader who joined the squad, didn’t like what she experienced, and took legal action. But to come back—not once, but twice? “I have trouble with someone who knows the rules, agrees to them, and then afterwards complains or sues or lies or is bitter.”

This must be the most common objection I saw in comments threads about the cheerleader pay issue. If you don’t like it, don’t do it. It’s a fair point, but not exactly the end of an argument. There are a lot of things we all do, hoping they might get better.

Dana and I debated this issue for a while, both of us engaged, respectful, but slightly unyielding. She pointed out that aside from the players and owners, nobody in the NFL gets paid big bucks. Cheerleading was designed as a hobby, never intended to pay your bills, and cheerleaders had to have a full-time job (motherhood counted) or be enrolled in school. I argued that someone of Erica’s stature made the lawsuit stronger, because otherwise it could be seen as sour grapes. I argued that legal action might be the only way to move the needle in an organization that kept playing that same old song. (Don’t like it? There’s the door.) And while it’s true that cheerleaders must have outside compensation, that structure made less and less sense as cheerleading ballooned into a full-time responsibility, with a reality show component and social media obligations.

There was a detail in the Erica Wilkins lawsuit that galled both Dana and me. It claimed that while star cheerleader Erica Wilkins never made more than $17,000 in any of her three seasons, Rowdy the Cowboys mascot made $65,000 a year plus compensation. I thought Dale Hansen was gonna fall out of his recliner when I told him that.

“While you could argue the cheerleaders are vastly underpaid,” he told me, “Rowdy’s also making about sixty thousand more than he should.”

Hansen never understood why so many women lined up for such a pittance, or how the Cowboys landed on the arbitrary number of $15 a game when the squad professionalized in 1972. “Tex Schramm’s bar bill was never once $15,” he quipped. But Hansen had also filled in as a judge at auditions, and he saw how ferociously the women were fighting for those 36 vastly underpaid positions.

“These women were coming in from all over the country, and crying because they didn’t get the job,” he said. “I thought, ‘Well, okay. If you’re willing to do it, I guess it’s not my place to lead the charge to fight for equal pay.’ But it’s a scam. I mean, it’s still a scam today.”

Whatever you call cheerleading—an honor, a stepping stone, a high-status low-yield side hustle, a Ponzi scheme—the Wilkins law suit did move the needle a bit. The cheerleaders’ game-day pay went from $200 to $400, and rehearsal pay went up to $12 an hour. But that still isn’t a drop in the bucket given the Cowboys’ oceans of wealth. To loosely quote Dale Hansen, Jerry Jones’s bar bill was never once $400. (Okay, maybe it was.) But according to an article I read on a sports site, water boys in the NFL make $53,000 a year.

So you’d think that Erica Wilkins would be congratulated for fighting. But Wilkins, who signed a nondisclosure agreement as part of her settlement, became persona non grata in Cowboys Nation. Former cheerleaders Melissa Rycroft (Bachelor and Dancing With the Stars winner) and Cassie Trammell (daughter of choreographer Judy Trammell) called her out on social media. “I am so disappointed that the organization that my mother was (and still is) a part of would even be remotely jeopardized by false allegations,” Trammell wrote. “It is not a career. I’m all for equal rights, but when we auditioned (and some re-auditioned multiple times) we all knew how much money was on the table.” (The post has since been taken down.)

It’s a weird twist that the woman whose lawsuit doubled the game-day rate for the cheerleaders wound up a pariah. “Deleted from the alumni database” is the threat that hovers over cheerleaders from any era. The alumni database connects hundreds of women across the decades for charity events, social gatherings, and Christmas ornament sales. Although the pay was lousy, the sisterhood was rich, and it’s no small reward to stay attached to the most lucrative and powerful sports franchise in the world. And although I’ve never confirmed that Erica Wilkins was deleted from the database, it would be my guess. It’s a fate that befell the women who posed for Playboy in 1978, several cheerleaders who have been kicked off the squad, and even former golden girl and onetime choreographer Shannon Baker Werthmann, who was fired by current director Kelli Finglass in 1991. (Suzanne Mitchell apparently called Finglass and had her reinstated.)

Dana thinks the change in compensation was coming anyway. The NFL knew it would have to pay more. She’d heard the murmurings at that NFL cheerleader alumni gathering in 2014. It frustrates her (I suspect it frustrates many cheerleaders) that media coverage intended to argue for better pay for the cheerleaders often portrays them as exploited workers and naïfs who didn’t know what they were getting into. Surely that’s true for some, but what Dana discovered was not how much the Cowboys took from her, but how much the experience gave her. Confidence, poise, leadership skills.

She did a soft-shoe to “Mister Bojangles” with Sammy Davis Jr. She experienced gunfire in Beirut during a 1983 USO tour, when the cheerleaders were riding home in a jeep after curfew and a bullet grazed Suzanne Mitchell’s head. Dana once held the hand of a soldier as he died. The cheerleaders were on an aircraft in Diego Garcia, and a giant hook dangling from a helicopter trying to land bashed in a man’s skull. He was not going to make it, and he was mumbling and delusional, and Mitchell sent Dana over to hold his hand.

“And I was just saying, ‘I know your family loves you, and you’re going to see them again.’” But he was not to. As he finally died, he gripped her hand. “That expression ‘death grip’—I know what it means now,” she told me in a solemn voice. “When you see people die in the movies, they relax. When that solider passed away, he grabbed my hand so tightly I had to scream for someone to help get his hand off of mine.”

She would never forget it. She would never forget any of it.

There’s an alternate reality in which Dana Presley Killmer becomes the director of the cheerleaders. It’s likely that Suzanne Mitchell had been grooming her for that position, though she ended up pursuing other avenues. And she loves what current director Kelli Finglass has done. “Kelli was born for that job,” she told me. Like Dana, Kelli had shown interest in the business side. Dana remembered one get-together at Suzanne’s ranch in Argyle where all the girls were gathered outside, but Kelli kept running inside to talk with Dana and Suzanne. She proposed a sponsorship with L’eggs pantyhose, their go-to brand at the time. Suzanne wouldn’t hear of it. “We’re the Dallas Cowboys,” Dana remembers Suzanne saying. “We don’t solicit. People come to us.”

But Jerry Jones, who bought the team in 1989, went a different direction. Sponsorships out the wazoo. Pepsi, the official soft drink of the Cowboys. Ford, the official truck of the Cowboys. AT&T Stadium has a miniature football field outside where kids can play, and it has one of those Instagram-friendly sculptures you see around town where it spells out a word but one letter is missing so you can stand where the letter would be. In this case, the word is LITE, as in Miller Lite, though it’s missing the I. One time I visited, I saw Boy Scouts taking turns inside that word, followed by a family taking a picture of their daughter. It was a weird scene.

And so the story changes, but many traditions held. Beautiful, talented women still show up each spring to vie for those 36 coveted spots. The dancing has become top-notch. Like many of the early cheerleaders I interviewed, Dana wonders if she could make the cut. “Someone my size would never make it now,” she told me. “I had curves and cheerleader thighs.”

But Dale Hansen still thought she set the bar.

“To me, every cheerleader who has followed her has one objective,” he said, in that authoritative voice that made everything seem final. “And that is to be somewhere in the conversation with Dana Presley. And if you can even work your way into that conversation, then you’re big time.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders